All According To The [Terrible] Plan

In 2008 one of the most important experiences in my life was making sure I argued with all of my friends about which movie was better; The Dark Knight? Or Iron Man. Meanwhile the world was experiencing one of the five worst financial crises in history that led to a $2 trillion loss globally.

Other than "The Great Bear Market of March 2020" that's about as close as I've come to seeing meaningful market cycles in my career. A lot has been said about what this downturn could mean for a career as an investor. Where some see it as the worst time to be a VC others see it as a gift. A defining moment for investors to experience what pain feels like.

What I've been surprised by is the bifurcation between what people think the "plan" should be for companies that are building right now. I've written before about the Tale of Two Markets that exist for private companies:

"You're starting to see a divide between founders and investors who are focused on "quietly building real products and steadily scaling real businesses" vs. those who are chasing exorbitant paper markups for businesses that don't have a very reasonable narrative to justify their price."

But the difference in company philosophy is more nuanced than "solid companies vs. grift shows." There is a fundamental difference in how companies CAN get built that are demonstrated in what the founder values.

Building Your Values

Some people would frame the decision as being between "grow at all costs" and "build a slow and steady profitable company." You can point to venture as explicitly existing to subsidize early stage company building so that they can burn money while chasing growth.

And that's not always wrong. There is an important discussion around what kind of company you want to build.

You can build a stable and profitable company while potentially sacrificing rapid growth, and there are plenty of examples of that with companies like MailChimp at $12B, Spanx at $1.2B, or Think-Cell for $1B+.

Or you can build a high-growth company by raising money to subsidize your early growth. Obviously plenty of examples of that, though to Matt's point, there are also several examples of companies that didn't nail the unit economics but raised and burned anyways.

There is even an argument for finding a "middle class" status for startups who may not have multi-billion dollar potential but can still be solid companies.

But the one key aspect of all of these potential outcomes? They have to represent the values of the founder. Founders have to decide ahead of time (usually) what kind of company they're going to build. And then they have to build their PLAN around those expectations.

The All-Powerful Plan

For those companies who expect to raise money and continue to burn cash unprofitably in pursuit of scale there has never been a more important time than now to have a clearly articulated plan. I've never read a better summary of the psychology and dynamics behind a startup's planning process than what Christoph Janz wrote in his piece "Hyper-growth is great, but don’t die while trying."

"Companies perform according to plan … until they don’t. That’s a tautology/joke, obviously. What I mean is that it quite frequently happens that companies go from “more or less according to plan” to quite drastically below plan in just a couple of months."

His entire piece is absolutely worth the read to unpack both the psychology (default optimism) and fundamental cash dynamics (slower growth exacerbates the problem of too much burn) that can impact a plan.

While VC money does exist to help businesses scale in the early days of company building that doesn't mean that they should justify poor planning, let alone poor execution. But for a lot of companies over the last few years? It has. The natural selection that exists among startups has been unable to work effectively.

"Companies that probably don't have a good enough idea, a good enough product, a good enough team, or a big enough market have been able to access exorbitant amounts of capital. A balance sheet flush with cash can hide a multitude of sins."

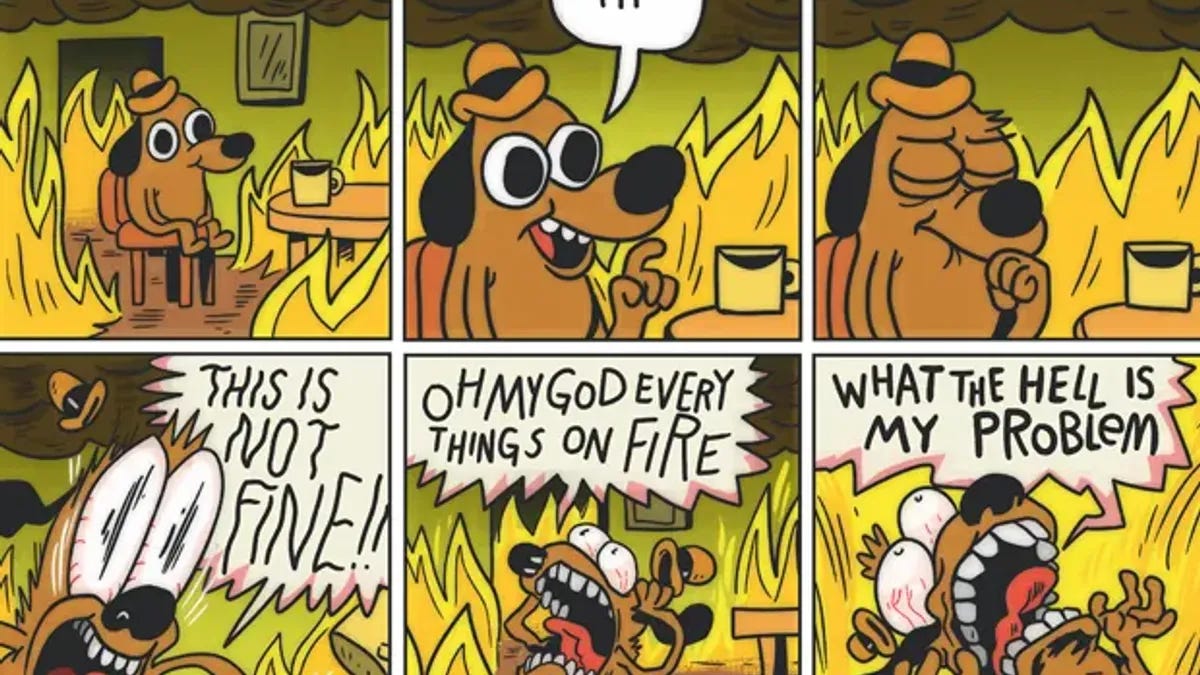

One of the things that a lot of folks could have planned for better is a point in time where access to cash might be more limited. For those companies that never had the right plan in place? The last few months have gone by really Fast and left a lot of people panicking.

Start With The End In Mind

Even if you want to build a high-growth startup with aspirations to become a multi-billion dollar company that doesn't mean those aspirations have to be divorced from a clear plan towards generating profits.

The companies that have been most impacted are those who have failed to demonstrate differentiated business models, sustainable growth, or a path to profitability. When you look at a company like Robinhood, at their peak they had a $42B market cap (25x revenue). They've plummeted to ~5x revenue ($8.7B market cap). At that multiple for them to achieve their previous market cap they'll need to generate $8B+ of revenue (they're currently at ~$1.2B). Ho Nam goes on to make the point as to why profits unlock a lot more flexibility.

"Buffett likes to say that he doesn’t like to depend on the kindness of strangers. Then adds that he doesn’t want depend on the kindness of friends either. Key is to be able to control your own destiny."

Controlling your own destiny is something very few companies have the luxury of. When you see companies as large as Uber just now starting to talk about unit economics more meaningfully that's the result of manufactured dependency. Not only a dependence on the expectations of Wall Street, who want to see profits more than they want to see their kids, but a dependence on an inflated market for cash.

“We have to make sure our unit economics work before we go big. The least efficient marketing and incentive spend will be pulled back. Now it’s about free cash flow. We can (and should) get there fast.” (Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber CEO)

In the Book of Peter Thiel, Zero To One, among the sacred Silicon Valley texts, we come across this "contrarian" idea: "A bad plan is better than no plan." Obviously when you're a seed stage startup without a logo or a domain you're unlikely to have a clear view of what earnings per share will be 7 years from now.

But planning is an exercise in storytelling. Articulate the story that you genuinely believe (not just the one you're selling to candidates, customers, or investors). And then constantly evaluate that plan to identify the dependencies you have.

You have a plan to add $3M of net new ARR this year. But what do your customers expect to pay? How long are the sales cycles they're putting you through? How likely is it that these customers will churn? That process of constant reevaluation of your plan is meant to simultaneously invalidate your plan while validating the plans existence.

Default Alive

Is venture supposed to help jump start early stage company building? Yes. Is it okay if they burn money to build those companies? Absolutely. But in planning for any particular outcome it's important to remember that most companies are default dead. Any plan should be a balance between the reasonable opportunity you can chase, the reality of the math that may lead to your companies untimely death and then contingencies for any of the things that could negatively surprise you.

"Assuming their expenses remain constant and their revenue growth is what it has been over the last several months, do they make it to profitability on the money they have left? Or to put it more dramatically, by default do they live or die? If the company is default alive, we can talk about ambitious new things they could do. If it's default dead, we probably need to talk about how to save it."

You shouldn't sacrifice your ambitious plans for the sake of security. But you also shouldn't naively expect your organic dependencies (customers willingness to pay or investors willingness to invest) to always show up the way you want them to. It's a balance.