This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Let me take you back to a time before the iPhone came out. Mr. Brightside by The Killers had just come out, and most people my age were getting their social anxiety kick from determining who our top 5 friends on Myspace would be. I would rush home from school, get some Taco Bell and Dad's Root Beer, and spend the next few hours in front of the computer world building.

The game? Age of Empires II.

I would build elaborate world's around different kingdoms, constantly thinking about how I would conquer more and more of the map. There's something primal in the competitive desire to control the playing field. Especially when you can summon a machine gun-toting Shelby Cobra.

In that game, the outcome was almost always zero sum. One person won and everyone else lost. In the actual history of conquest, that's rarely the case. Almost every empire that's been built has done so with allies. Collaborators in attempting to control more of the known world.

Building businesses isn’t so different. Sometimes for a company to go the distance, they have to embrace "Simul Fortior." Stronger together. Occasionally, that collaboration comes willingly. Other times? A combination of competitive forces and macro conditions force collaboration, whether you like it or not. The alternatives become collaborate, consolidate, or die.

The Music Has Stopped

The reality of the macro economic environment is that the music has very much stopped. Publicly traded tech companies are, on average, down ~48% YTD. Companies like Okta, Twilio, and Asana are down over 75% YTD.

The reality of the game on the field has been endless access to cash. With rates low, providers of capital were desperate for yield. So, many flooded into funding tech companies that could use that cash to push towards extreme growth. In the startup world, this often meant that certain attractive categories could have a dozen companies, all effectively the same, but that are getting funded to tackle the same market.

But what happens when all that money suddenly gets sucked out of the room? Lit on fire? Those categories that have been, in some cases, over-funded, start to wither. They all start to look for every dollar they can get, and more often than not 1-2 players start to emerge as the dominant player. In a world that funded 12+ companies, only a few might survive.

One reason the shut off of access to cash causes this atrophy in a crowded space is because most of them, built to chase growth, structured their strategy around unsustainable customer acquisition costs. Couple of examples? Uber vs. Lyft. Bird vs. Lime. Casper vs. Purple. Most of these companies saw drops in valuation from billions to millions. Many of them are built on an unhealthy reliance on paid marketing.

The same is true in the B2B world. When you have tons of companies getting funded that are offering similar nominal product improvements, and then pouring fuel onto a GTM fire, you're going to have a lot of outbound sales that go unanswered. So you're spending more to acquire those same customers, since all your competitors are out there with very similar messaging.

When capital is plentiful? They're all competing for the same subset of customers, driving prices down and acquisition costs up. When the cash spigot gets shut off? It exposes a multitude of sins, and they have to start to think about how else to own a category, other than just spending like a drunken sailor.

One path forward? Consolidation.

A Cleansing

One important thing to note is that, while this starvation of capital is painful for a lot of people, it is healthier for the ecosystem. I've written before about a tweet that Harry Stebbings deleted. It was a hot take, but I think there is a lot to be learned from his insight:

"Effectively his point was that there is a natural selection among startups. Not every company will survive and it can be a healthy recycling of talent back into other companies. In a world of abundant capital fewer companies are dying, which means talent doesn't recycle as often."

His focus was on the recycling of talent, but the same idea can be applied to all the resources available. When you have limited resources, people are more likely to be forced to collaborate, consolidate resources, and increase their chances of success.

I've written before about a venture fund that got started in 2008 in the middle of the financial crisis:

"The only people starting companies in that kind of bust period are really serious about it. So the talent becomes more clustered. For instance, if you have four people who are really good at what they do in a 2008-type period, they come together to start one or two companies. [In good times], they’d each start their own companies."

In a world of too many companies, and not enough capital, there will be a wide spectrum of outcomes. Unfortunately, not every company will survive the correction. There will be startup death, and that has to be met with a significant amount of grace and respect. Building a company is never easy, but it is particularly difficult right now, as the world falls apart.

And even for those companies that are able to sell themselves, it won't always be a measured transaction where there is value going both ways. A lot of companies will go in a fire sale, whether to avoid layoffs or to save face, it will be a transaction that look like a soft landing, but structurally isn’t all that soft.

But there is a landscape for M&A that I'm excited about as we get to dream what the sum of the parts could be for some phenomenal companies as they look for ways to come together.

What To Expect

Granted, I'm not the first person to predict this kind of onslaught in M&A. Bankers at Goldman Sachs are expecting a wave of M&A among private tech companies in 2023. They put it this way:

"Consolidation among private tech firms is set to pick up—especially among startups that had to abandon hope of going public this year. A dramatic drop in tech stock prices has derailed firms, including Instacart and Reddit, that were gearing up for initial public offerings. The same drop in prices, though, makes it easier for acquisitions to get done. And with fundraising for startups harder, competing firms that proliferated during the era of cheap venture funding may start to feel pressure to consolidate."

There are a lot of different kinds of acquisitions. Different companies will be trying to solve for different things; both the acquirer and the acquired. Whether it's largely about talent (an acquihire), intellectual property, or just customer penetration.

In some cases, acquiring a company whose been able to acquire a lot of your target customers is an effective way to quickly grow your market share. Though, that isn't always the case. Take Robinhood for example.

Right now, Robinhood is valued at $7.8B and they have 15.9M MAUs. For another brokerage like Charles Schwab or a bank to acquire Robinhood, they would effectively be paying $520 per customer. Customer acquisition costs for a typical brokerage or bank run from $200 - $500 per customer. It's cheaper to just keep acquiring customers through their normal channels than it would be to acquire Robinhood.

But there is a lot of accretive acquisitions out there that could lead to "total > sum of the parts" outcomes. By and large, I'm going to avoid calling shots about specific transactions, and more just try to illustrate the types of transactions I'm excited to watch out for.

Big + Big

The most splashy acquisitions we sometimes see are large corporate mergers; near combinations of equals. Some of them turn out to be pretty terrible, like the combination of AT&T and Time Warner. Most of these deals have played out in CPG categories, like Kraft + Heinz, or media like Disney + 20th Century. You have some large tech acquisitions, like Dell buying EMC for $67B, but those don’t often work out. In tech, most of the best acquisitions come from larger players buying an innovative smaller player to bolster a different aspect of the parent company's business.

Big + Small

These are often the most well-known acquisitions. Facebook buys Instagram. Google buys YouTube. eBay buys PayPal. Disney buys Marvel. As crazy as the numbers may make this sound, even recent acquisitions like Activision being acquired for ~$70B by Microsoft is a bigger player buying a smaller one, when you consider Microsoft's $1.8 trillion market cap. Or Adobe buying Figma for $20B, when their market cap is ~$150B.

This is certainly one area of M&A that I'm excited to watch. There are a number of companies that are bolstering their product platforms, and expanding their addressable market that would love to snap up some innovative additions. Snowflake, even after dropping ~57% YTD, is still valued at $45B and has $3.9B in cash. They've already acquired StreamLit for $800M. Between cash and stock purchasing power, there are a lot of companies who will struggle to live up to their valuations, and more than a few of them are in data infrastructure, one of the hottest categories in 2021. Just take a look at their partner ecosystem. Lots of interesting targets.

Datadog is worth $23B and has $1.7B in cash. CrowdStrike is worth $31B and has $2.3B in cash. Not to mention bigger names like ServiceNow, or smaller names like GitLab, and then there’s the ever-hungry likes of Microsoft, Google, and Amazon.

Small + Small

One area that, while not as common, I expect to see some of in 2023 is the combination of smaller companies. These might be companies valued at a few billion each, but they're pretty early days in terms of revenue. In 2021, we saw a massive proliferation of point solutions; companies that could get funded without much path to becoming a large multi-product platform. Those point solutions will increasingly find it difficult to meaningfully compete or attract enough capital.

Like Ankur mentioned above, this is a "great time to be a savage founder with a balance sheet." These kinds of transactions won't be easy, because there is a lot of ego at play as people try to build large businesses. But when your options are quickly dwindling, and approaching binary territory where it’s either sell or die? There will be opportunities to transact.

Aggregators

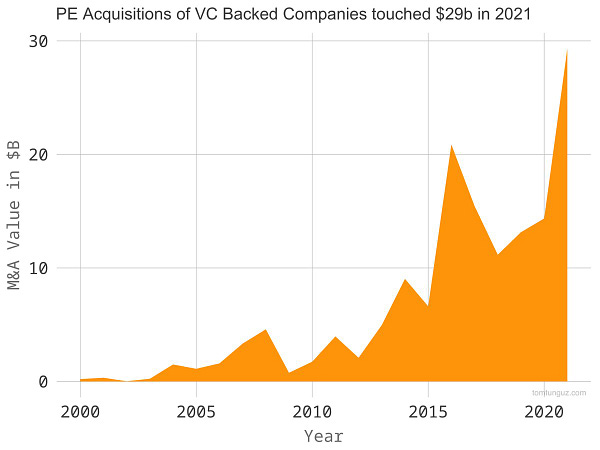

PE acquisitions

Another approach to watch is firms whose models are built around aggregating interesting companies. The most common player here? Private equity.

Private equity can account for massive acquisitions, like Vista's $16.5B acquisition of Citrix, or Thoma Bravo's $12.3B acquisition of Proofpoint. But there are hundreds of PE firms buying up software companies for much smaller outcomes. This can represent a perfectly good home for software companies that are smaller, and have slowed their growth. Like Thoma Bravo's $1.3B acquisition of UserTesting; that’s a smaller company, <$200M of revenue, growing ~40% YoY.

Roll up Vehicles

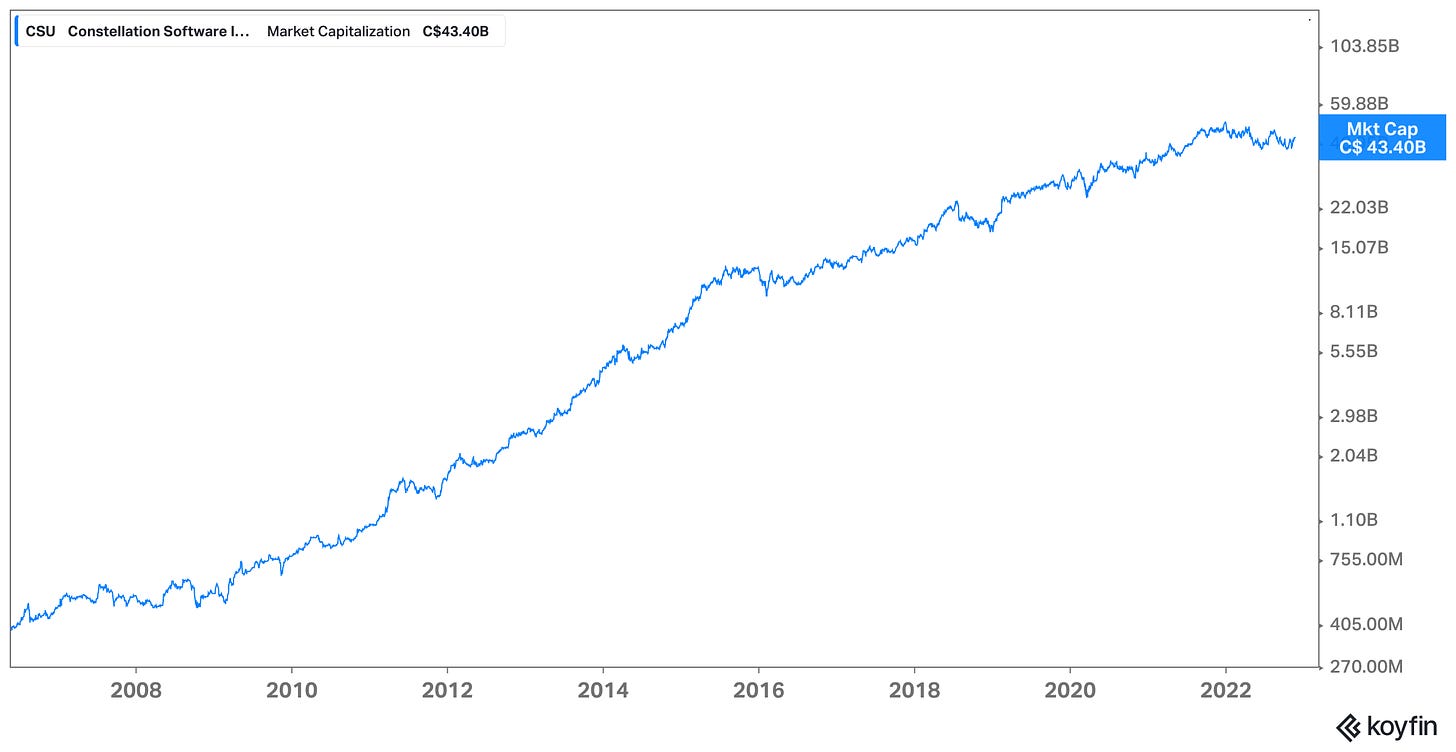

Other interesting things to look out for are aggregation plays. One of the very best examples of this is Constellation Software.

"Constellation has acquired more than 500 [vertical market software] businesses spanning over 75 verticals from digital marketing to manufacturing, library management to yachting."

In the last 10 years, they've grown from ~$800M in revenue to over $6B in revenue. They've grown 100x to a $43B market cap, all while rarely buying a business doing more than $2-5M in revenue.

This might be a weird comparison to make when talking about venture-backed startups, but the reality is there are over 1K companies valued at $1B or more. My guess is that ~75% (if not more) of those companies will never live up to their valuations. Not for lack of trying, but many of them will run out of cash before they’re able to justify a $1B+ price.

So where do those companies go? They shut down. They find acquisitions at big players, or smaller peers. Or? Aggregation plays step in to help facilitate transactions that are closer to the economic reality of these businesses. Platforms like Acquire.com (fka MicroAcquire) are already trying to make these transactions more seamless. We'll see more of this.

Predictions

Now, like I mentioned before, I'm going to avoid calling shots about specific companies or transactions, and more just try to illustrate the types of transactions I'm excited to watch out for. Some of these might include aggregating up to existing platforms (e.g. Salesforce, Zendesk), but what will be interesting to watch is how these categories consolidate.

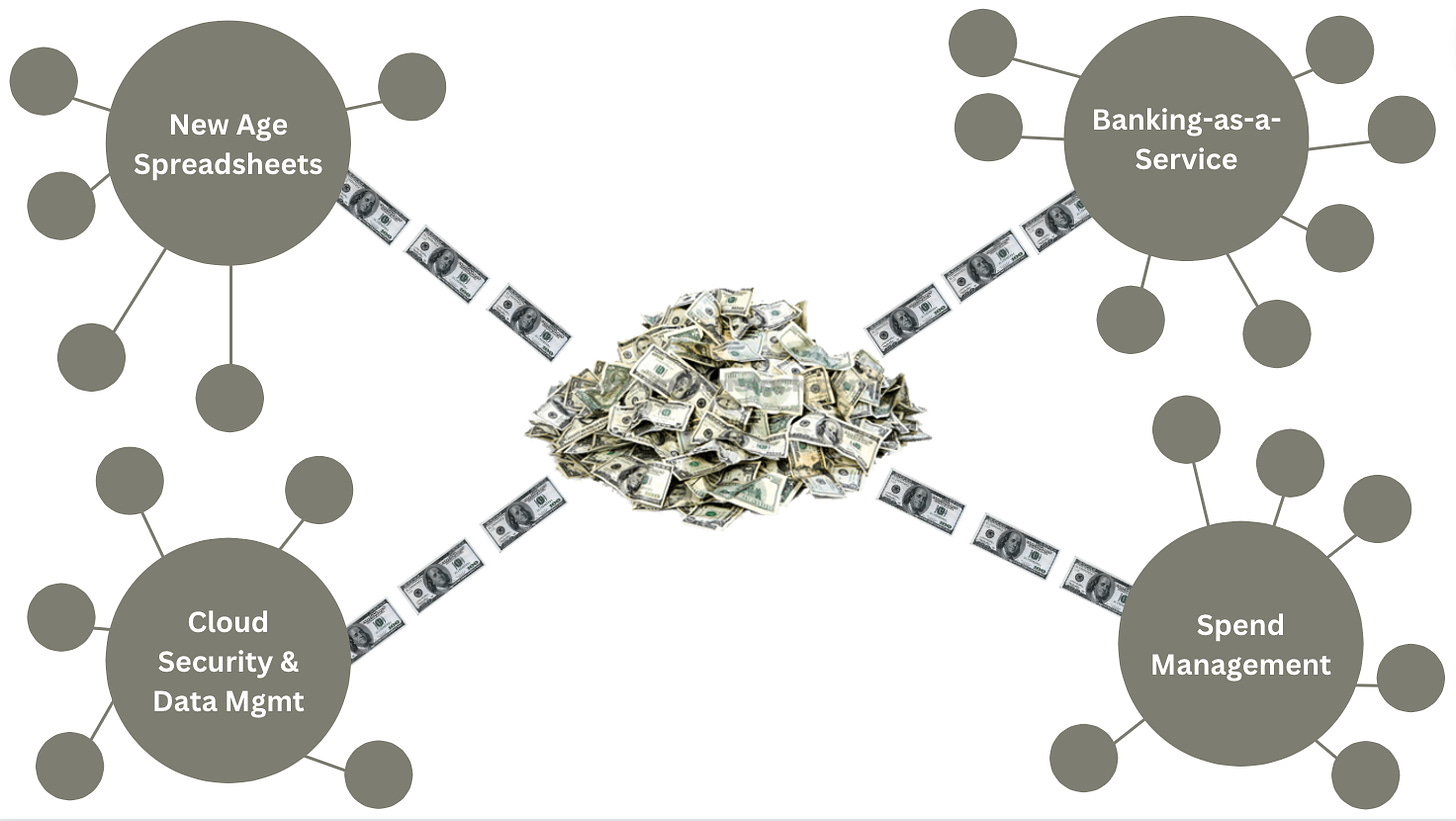

Here are a few categories that it feels like there are potentially too many players, and there opportunities for 1-2 of these companies to start to stand out as the leading platforms of the next generation, and for the rest to open up to consolidation.

Cloud Security: Wiz, Orca, Lacework

Customer Support: Zendesk, Gorgias, Ada, Freshdesk

Marketing: Salesforce, Marketo, Attentive, Klaviyo, Postscript, Braze

No-Code Builders: Webflow, Bubble, Airplane, Budibase, Retool

Spend Management: Ramp, Rippling, Brex, Balance, Expensify, Pleo, Spendesk

Banking-as-a-Service: Unit, Bond, Syncterra, Treasury Prime

Cloud Data: Eureka, Sentra, Cyera, Laminar, Normalyze

Data Pipelines: Fivetran, dbt, Airbyte, Monte Carlo, Datafold

API Tooling: Postman, Kong, Salt Security, Noname

Data & Machine Learning: Databricks, Hugging Face, Weights & Biases

DevSecOps: GitLab, Snyk, Veracode, Cider Security

Who knows if any of these will be the most accretive combinations, or if these names will end up getting snatched up not by each other, but by larger ecosystem players. Some of these companies could be acquired, but many could be the acquiror. These are the kinds of categories where, even beyond the names listed here, there are a LOT of funded players. And there is unlikely to be room for all of them to survive as standalone businesses

What Does This Mean For Venture?

The simplest impact in venture is the need for portfolio support when it comes to navigating the complex waters of M&A. How to sell? Who to sell to? How to run a process? That will become an increasingly valuable skill over the next 12-24 months.

But even more interesting than that, I don't think VCs will be just indirectly impacted by the Age of Acquisition via their portfolio companies. This same dynamic could impact venture firms themselves. I've written before about the potential consolidation coming for venture firms:

"Over the last few years the number of venture firms has grown from ~900 to nearly 2,000 different firms managing $500B+ of capital. In a market correction some people predict as many as 50% of those firms could fail. One prediction I have is that as venture funds have become more productized they've developed more IP and proprietary processes. As a result, even though you'll still see some firms shut down I also believe you'll see some venture firms get acquired. Not only for their portfolios or people, but for the things they've built."

So why would you acquire a venture fund? In some cases, its just a coming together of disparate strengths. The rise of the solo capitalist may give way as these solo GPs acknowledge the struggle in fundraising, now that capital isn't as free-flowing, and they'll look to combine forces with complimentary investors. Those consolidations will likely end up looking like fairly traditional venture firms when all is said and done.

What other assets have venture firms built?

Data Platforms: SignalFire, Tribe Capital

Talent Ecosystems: Artisanal Ventures, Kin Ventures

Function Specialty: GTMFund, Designer Fund

Maybe those specialized firms become valuable assets for larger platforms to acquire, and bring into a larger existing ecosystem. Again, when capital is plentiful, everyone wants to run their own fund. But when the capital dries up? Some people will find it can actually pretty nice to have a big platform at an established multi-stage firm.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

this is a great post. you have excellent explanatory skills.

great post