The Audacity

Picture this. A company pitches you on the idea of selling anime comic books online. They'll have the broadest collection of anime in the world because they'll let anyone selling anime sell from their platform. Maybe you know anime is a $24B market so you're a little bit interested.

Now they tell you within a few short decades they'll have built the largest logistics network in the world, not only to deliver anime, but anything you could want. On top of that they'll be powering 1/3 of the internet. Do you actually buy that?

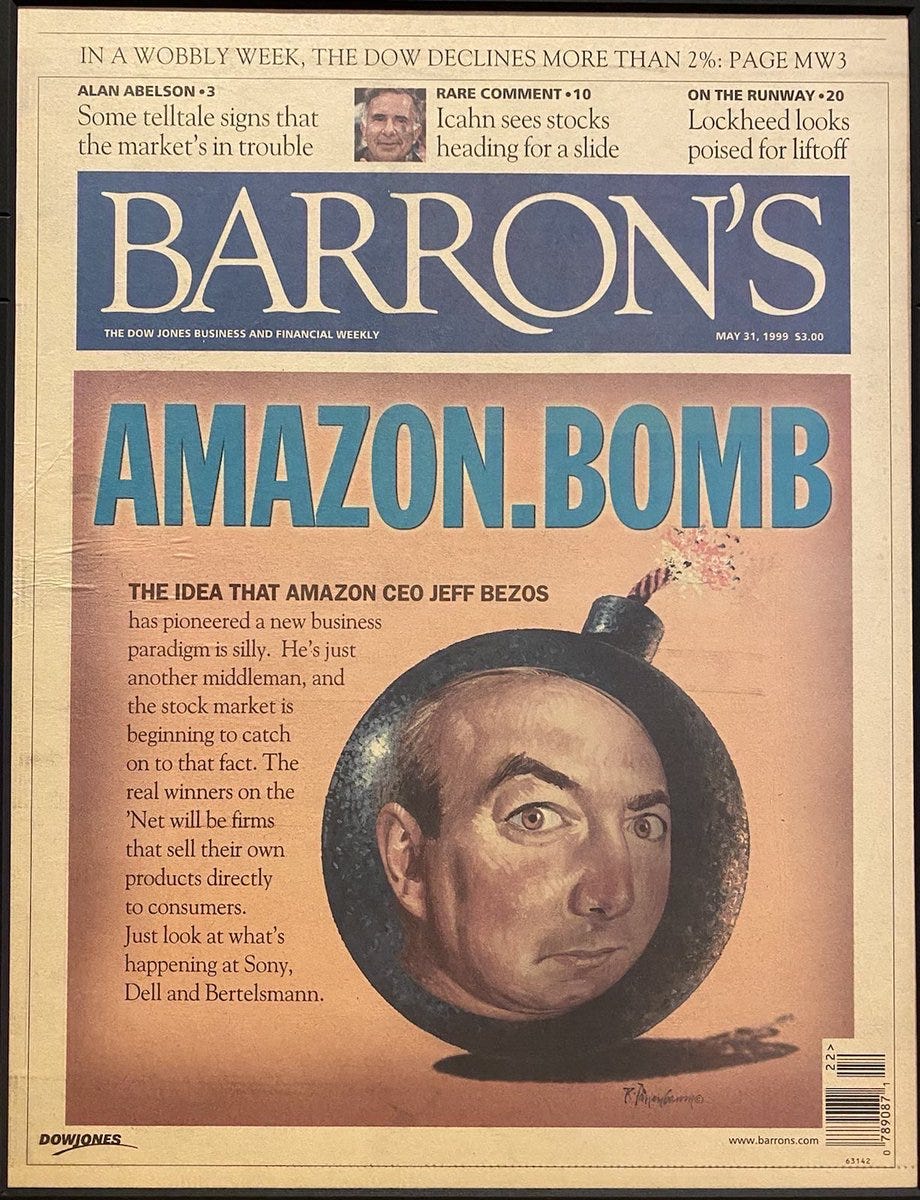

The story may be all too obvious, but this is effectively what happened with Amazon. I think all the time about the audacity of being able to buy into the vision of world domination for Amazon back in 1999. And a lot of people didn't buy it.

But when we look around at the market correction today I think a LOT about the necessity of not only having near-perfect execution but a massive vision that is anchored in a "right to win" that you're creating today. Amazon is a pretty phenomenal example of that. But first? Some context.

A Weighing Machine

I've written before about a famous quote from Warren Buffet's sensei, Ben Graham:

“In the short run, the market is a voting machine – reflecting a voter-registration test that requires only money, not intelligence or emotional stability – but in the long run, the market is a weighing machine.”

Right now everyone is voting with fear in the public markets. What is the bear case for every company? And then any negative impact from a recession, inflation, or global supply chain issues is seen as verifying evidence for this 'kiss of death' moment we're in.

But what did he mean by a weighing machine? Another quote by Semil Shah has really stuck with me over the last few months:

"Companies big and small will be examined through the lens of growth narratives driven by product diversity. It’s no longer good enough to just handle online storage, or to just facilitate online meetings, or to just empower consumers to freely trade securities. [Investors] are likely going to reallocate their money into companies that demonstrate the vision and execution to not only acquire assets like Instagram and WhatsApp, but also key infrastructure like Parse and Onavo; or assets like Slack and Tableau; or assets like Minecraft, LinkedIn, and Activision. The public markets will likely reward those companies who can diversify their product lines into messaging, analytics, gaming, and more — those special companies and business leaders who continue to bundle value into their platforms."

While this is most dramatically true of public investors who are seeking safety in established platforms this philosophy will also continue to be much more relevant as venture investors consider what investments they want to make.

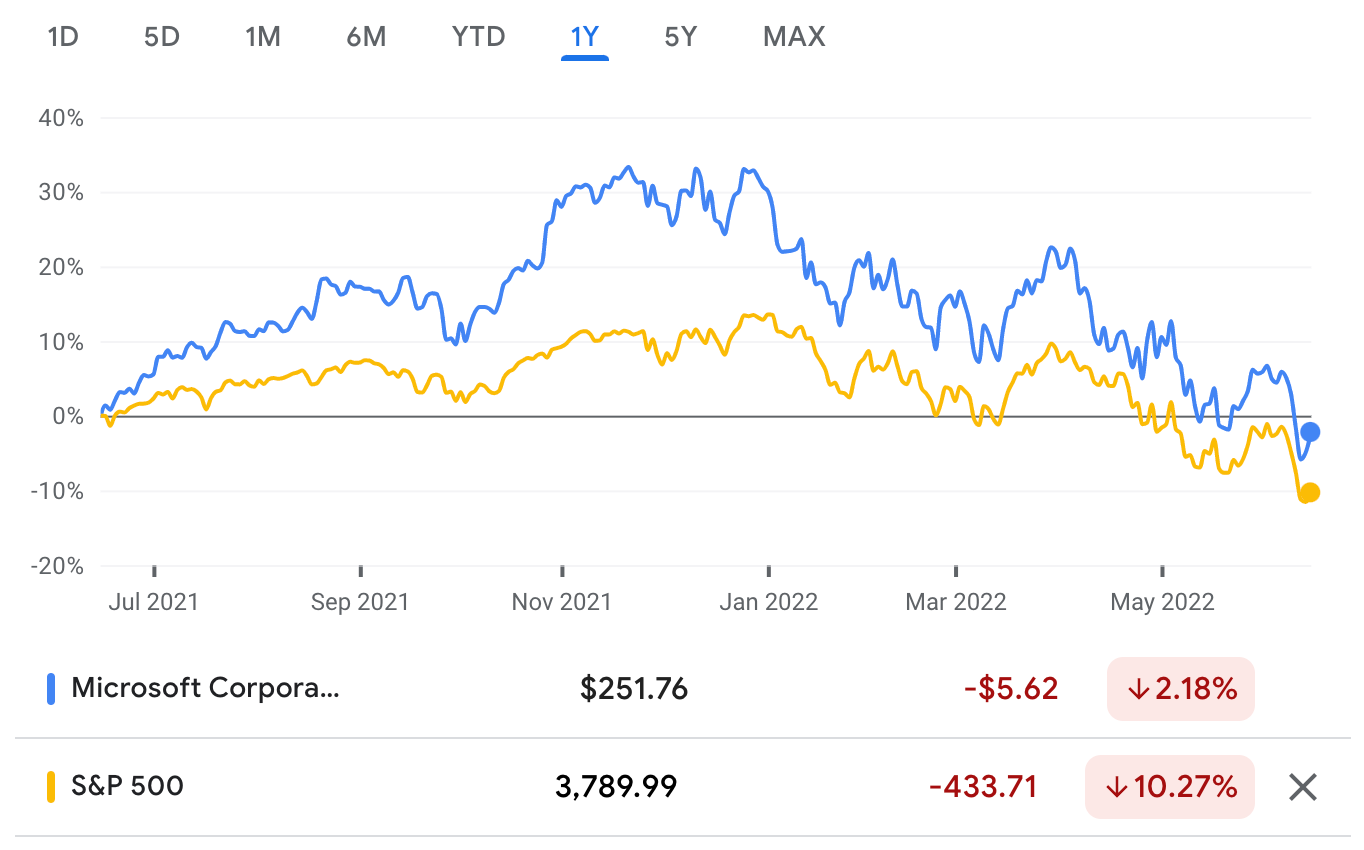

Semil's most poignant example was Microsoft. It's insane to consider the fact that the same company responsible for Windows OS and Azure also own properties like Linkedin, Xbox, Activision (almost), and Github. Everyone is down but overall Microsoft has held up relatively well this year compared to the market.

Venture investors are reeling from this market correction because it resets a lot of assumptions about the valuations they can pay since the size of the outcomes they have to look forward to have likely shrunk.

If a company only has the ability to offer one thing then it's harder to see a large outcome. If they're only offering that one thing and it's in a very small market that's nearly impossible for a VC to get comfortable with.

Let's look at Amazon as an example of the kind of mega bull case that VCs are trying to imagine in the companies they evaluate as they search for "venture scale."

Amazon: a Case Study

When you look at what Amazon has been able to accomplish you see a dream come true for venture investors who are trying to really "dream the dream" of what a company could be capable of. Going from an online bookseller to a trillion dollar juggernaut spread across ecommerce, grocery, entertainment, cloud computing and so much more.

Building a Product Engine

In Brad Stone's book The Everything Store he quotes Danny Hillis, a friend of Jeff Bezos', about the unique qualities of Amazon:

“If you look at why Amazon is so different than almost any other company that started early on the Internet, it’s because Jeff approached it from the very beginning with that long-term vision. It was a multidecade project. The notion that he can accomplish a huge amount with a larger time frame, if he is steady about it, is fundamentally his philosophy.”

What struck me when I read both The Everything Store and Amazon Unbound was the intense commitment to experimentation that Amazon has as a culture. The willingness to tackle "big hairy ambitious goals" without the same institutional fear that other large organizations have. Take, as an example, Amazon's experience trying and failing to launch the Fire Phone.

"Bezos didn’t penalize Ian Freed and other Fire Phone managers, sending a strong message inside Amazon that taking risks was rewarded. Ian Freed, the vice president in charge of the project, said “I made a mistake and Jeff made a mistake. We didn’t align the Fire Phone’s value proposition with the Amazon brand, which is great value.” Freed said that Bezos told him afterward, “You can’t, for one minute, feel bad about the Fire Phone. Promise me you won’t lose a minute of sleep.”

Because that experimentation is allowed and taking risks is rewarded you create a culture that can build a massive product engine. Once you have that engine churning through ideas you occasionally have massive hits like AWS.

Having great ideas and a muscle to execute towards them is great. But it isn't enough alone. A lot of startups will pitch a massive vision of how "we're doing A because it leads to B which will set us up for world domination as we build towards C." But one key thing is missing.

An Unfair Right to Win

Jeff Bezos talked constantly about customer obsession. One critical byproduct of Amazon's ability to build a powerful product engine was that this customer obsession gave them a unique right to win because they had a clearer perspective on what customers wanted. He said once about their advantages as a company:

“We don’t have a single big advantage. So we have to weave a rope of many small advantages.”

Any company who pitches themselves as a "special [company] who [can] continue to bundle value into their platforms" can't base that ability on hustle or brand or grit. An advantage comes from something inherent in your product today and then you "weave a rope" of those inherent advantages towards the long-term vision of building a platform.

As a venture investor you'll hear pitches left and right about how doing one thing leads to becoming the system of record or the operating system for a particular category. The reality is those true platforms get built very rarely.

Realistically Rare Right To Win

Most tech companies are stuck between a rock and a hard place along the journey to becoming a platform. On the one hand a company's long-term success is dependent on continued growth, so you have to constantly be identifying the sources of where that growth will come from. On the other hand sustained growth requires a "clear right to win." And that right to win is highly elusive for most companies. Why?

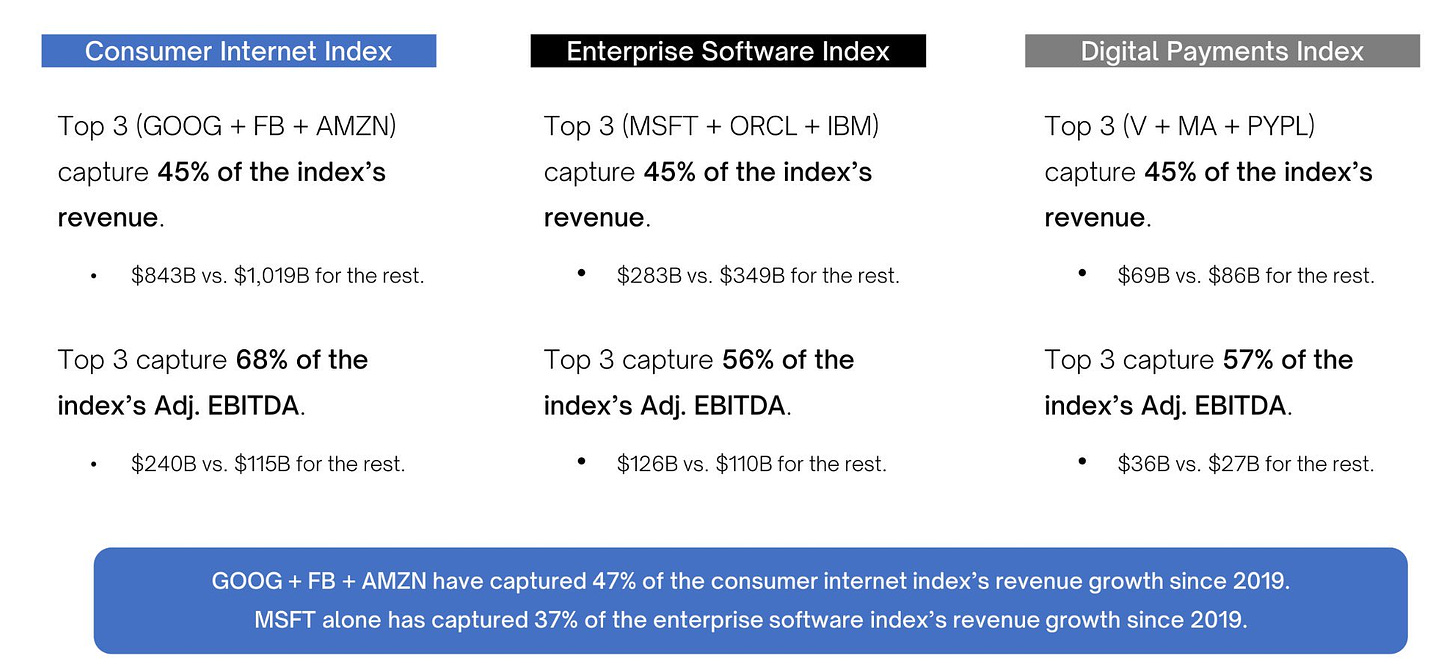

Tech companies naturally lend themselves to ubiquity. The bigger you are the more data you have to learn from, the more customers you have for distribution, and the more mindshare you have to attract employees and partners. Across consumer internet, software, and payments the largest revenue shares go to just a few companies.

As much as companies pitch their long-term platform vision they have to contend with the existing ecosystem of players and their more natural center of gravity. I've written before about the struggle for ubiquity in categories like productivity software:

"The problem with this idea of ubiquity and grassroots awareness acting as a moat is that it doesn't play out in productivity software. There is very rarely an intense stickiness for application software."

Even though Slack has significant penetration across a wide variety of customers they still had to contend with the ubiquity of a much broader platform: Windows. Microsoft was able to use their OS as automatic distribution for Teams. That doesn't mean that Slack is invalidated as a product, but it severely damages their "right to win" across all types of customers. Heavy Microsoft shops will likely opt for an in-ecosystem tool like Teams.

Look at a few other examples within ERPs or neobanks.

ERP Juggernauts

When you talk about an entrenched and ubiquitous group of incumbents look no further than the world of SAP and Oracle. As painful as these tools are to use they still control a massive chunk of the ERP market.

The closest anyone has come to making a dent in their market share are companies like Coupa ($4B market cap) in procurement and Bill.com ($10B market cap) in bill pay. They're competing with subsets of the ERP juggernauts like SAP Ariba or Concur. But when you compare Coupa or Bill to SAP ($113B market cap) and Oracle ($181B) you can see the implications of ubiquity.

Companies pitching themselves as new-age ERP entrants can point to the vision of becoming a piece of the pie here or there but their "right to win" will have to be in context of what advantages they have over the existing centers of gravity.

The Neobanked

The majority of consumer fintech companies pitch this idea of creating an initial "wedge" with a particular demographic that gives them the right to then expand dramatically and offer additional (usually higher margin) products to their existing customer base.

Most neobanks are CAC machines where they spin up significant marketing costs to acquire customers. More and more you're seeing pitches for specific demographics like kids and teens, couples, or even gamers. By identifying their unique demographic they hope to build a much more effective customer acquisition engine because they can be highly targeted.

The biggest obstacle these companies will face is the same uphill battle against ubiquity. Banking is all about building scale and that leads to a similar "center of gravity" dynamic where the biggest players continue to get bigger.

Any consumer fintech business has demonstrate their "clear right to win" against those centers of gravity and the reality is there aren't very many successful examples. Public markets seem to have a fairly limited appetite for neobanks even when unit economics are strong which leaves even less room for experimentation. That doesn't mean all sorts of fintechs can't be successful but when you're making the argument for your right to win as you broaden your product suite it's an uphill battle.

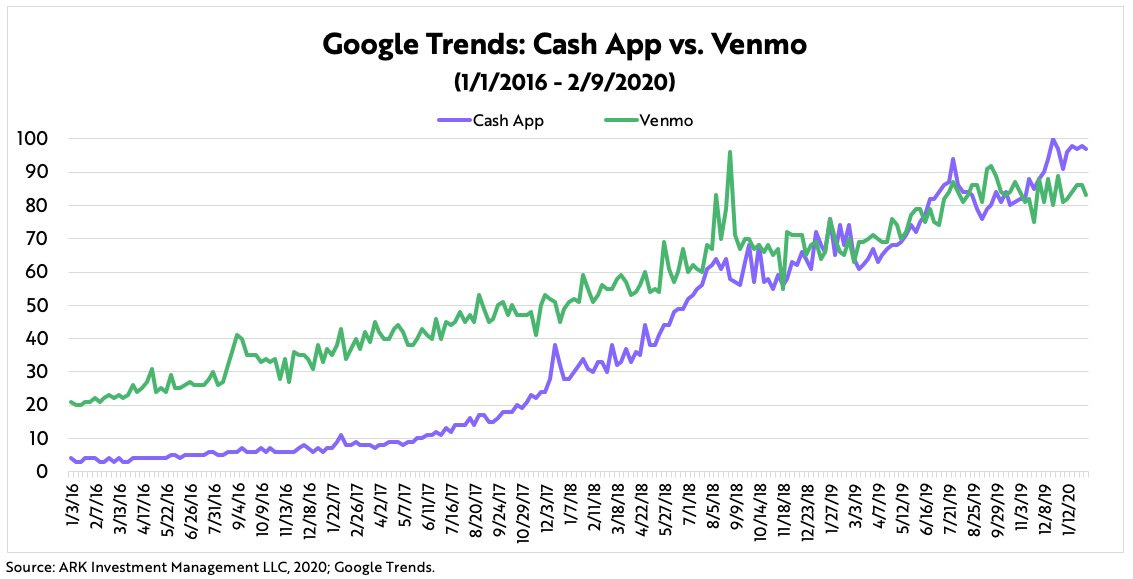

The more likely outcome in neobanks is similar aggregation to what we've seen in traditional banking (like James points out; ~50% of deposits in top 4 banks.) You're already seeing this with the success of incumbent fintechs launching products that become dominant. Cash App is a great example.

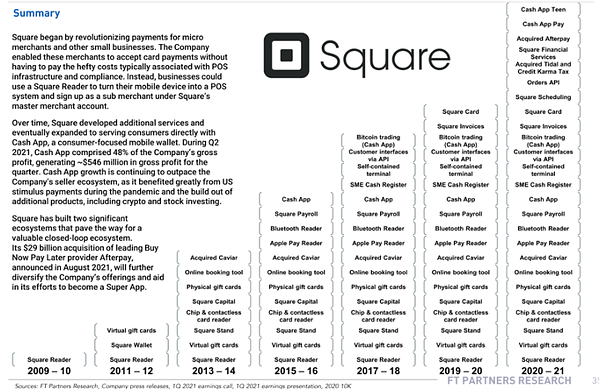

Cash App has become a cultural phenomenon that no bank has experienced. Cash App as a standalone unit has continued to ship features and products that keep them relevant, but this is a reflection of the broader product velocity that Square has shown over the last 10 years.

Another example of product velocity is what we're seeing coming out of financial Infrastructure companies like Stripe and Plaid. Stripe launched two products in the first 5 years and then proceeded to launch 10+ more in their second 5 years. Plaid is starting to follow suit launching KYC/AML and data connectivity just this year.

What Does This Mean For Venture?

Many people laude the success of zero to one companies. When you've built "something" from nothing it really is exceptional. But just as difficult as it is to be something its also difficult to build "something else" for the first time. Becoming a multi-product company is an intense journey. Bucco Capital calls this capability "economies of scope." The ability to expand TAM by introducing new products.

As VCs see the size of their investments' potential outcomes continuing to shrink in a market correction we become laser focused on companies that have the team, product, and market that could allow for economies of scope. Many later stage companies pitch their ability to acquire their economies of scope through other companies down the road. But while that might work for third products and beyond, there is a muscle that has to be grown in terms of becoming a multi-product platform.

For VCs looking to invest in the next great platforms they’ll be looking for (1) well built product engines, (2) a clear indication of an unfair right to win, and (3) a market big enough to sustain a hungry ambitious product machine.