This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

My sons are 6 and 3 years old. That age gap presents some interesting similarities and differences. Similarities? They both love playgrounds. Differences? My 6-year old is way better at convincing my 3-year old of things, and my 3-year old is way worse at knowing when his brother is wrong.

At one point, they were playing at a playground where there was a winding slide. My 6-year old had made it down, and was trying to coax my 3-year old down the slide. "I'll catch you!" My 3-year old was nervous, but had the promise of a soft landing to give him some confidence.

Unfortunately, my 3-year old misjudged two things: (1) winding slides are pretty hard to navigate when you haven't developed all of your motor skills, and (2) my 6-year old has no idea how to catch his little brother.

He took off, slamming into just about every turn on the way down. When he came to the end, looking expectedly for the safety net of his brothers arms, my 6-year old had his arms up in the air, and was 5 feet from the bottom of the slide. My 3-year old was certainly not going to clear the distance, and was headed down, not up. His only landing was the ground.

Moral of the story? Sometimes, neither the journey nor the destination are what we expect. Here's a jarring transition if there ever was one. First, let's talk about some venture fund mechanics, and then dig into some of the 3-year old-esque expectations that some in the startup ecosystem may have.

Some Context

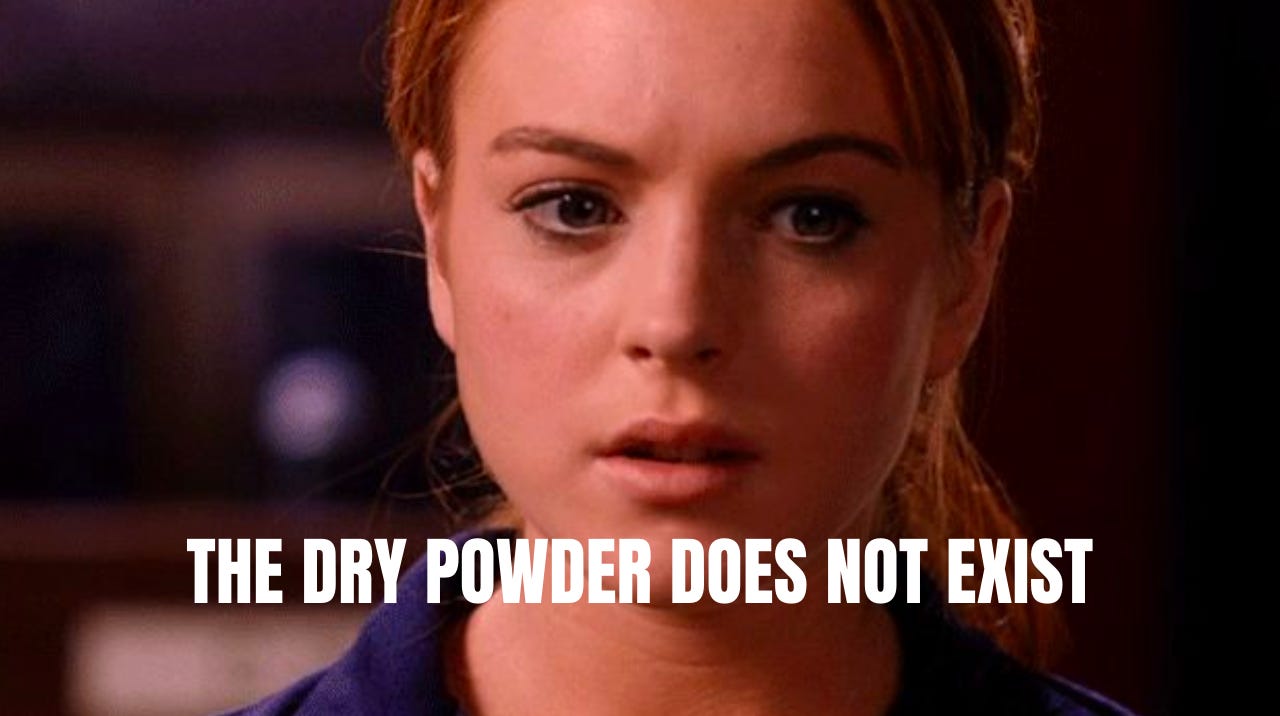

As a quick primer on how venture funds work, let's talk about fund lifecycles. A typical venture fund goes through several phases over the course of its life. Usually, the entire cycle last 10 years. If you raise $100M fund, you don't get any cash on day one. The LPs (wealthy people, family offices, pension funds, etc.) sign an agreement that they'll send you the money when you ask for it.

Over the course of the first few years, you’ll start making large capital calls so that you can make investments. After the first 2-3 years, that pace will slow down, you’ll be making fewer investments, or mostly just making follow-on investments. By year 6-7 for that fund, it's just a waiting game. You’ve probably raised another fund and am deploying that, so for my previous fund I'm just helping and waiting for exits.

What's most important to understand about this is the incentives that exist in that fund. To keep raising funds, VCs need to demonstrate to LPs that they've generated returns, whether on paper, or cash returned. A lot of investors talk about the focus being on distributed to paid-in capital (DPI), which is actual cash returned to LPs.

But across the board, the focus is on demonstrating returns. Some of the measurements funds can use to articulate their returns are (1) MOIC, and (2) IRR. The multiple on invested capital (MOIC) is the x-factor of the value of your fund based on markups, which translates to dollars, but doesn't factor in time. A 2x return in 3 months is great. A 2x return in 30 years is not great. Then there's the internal rate of return (IRR) which takes into account the passage of time. That 2x is true whether its 3 months, or 30 years, but IRR drops dramatically if the return takes 30 years to manifest.

So, why am I talking about this? The difference between these metrics is driving an important difference in the world of venture investing right now.

A Hollow Hope

For several months, people have been pointing to the record levels of "dry powder" in venture funds. These are the funds that have been raised, but not deployed. Some people compare the coming onslaught of dry powder to gravity, an undeniable force.

And it's fair to say, there is a lot of capital raised. But comparing dry powder to the force of gravity is a misrepresentation of the forces that drive capital allocation; it isn't nature, it's nurture. People and incentives are the most important force to understand when it comes to capital.

Where Has All The Capital Gone?

Michelle Valentine, the CEO of Anrok, explains the reality that most LPs are facing. Because they don't invest cash into venture funds at the beginning, a LOT of that dry powder isn't just sitting on the side lines, its been hunting for yield in the interim.

"Remember those LPs who still had two-thirds of their capital obligations to venture firms outstanding and decided to invest in short-term holdings to earn interest in the meantime? Their short-term holdings are now worth a fraction of what they originally expected. They may be forced to sell positions at a loss. In some cases, they simply may not have the capital to commit."

As a result of this mismatched dynamic of LPs that have overly illiquid portfolios, dramatic underperformance, and liquidity demands (like paying out pensions), a lot of VCs have started to refer to this dynamic as "wet powder."

People think that the reality of "raised capital" has a time crunch on it because of the dynamics we discussed earlier. The longer you wait, the lower your IRR, right? But here's an important nuance. IRRs don't start until VCs call capital. So for example, if someone raises a fund in January 2018, and doesn't invest in a company until December 2019, the clock on their IRR starts December 2019, not January 2018.

A somewhat common practice in private capital funds (PE, VC, etc.) is to use a subscription line of debt to manage their cash flows. In normal times, LPs don't want to be getting capital calls every few weeks, its just a logistical nightmare. So VCs will have a line of credit. When they make an investment, they can draw down debt, make the investment, and then at the end of a quarter or so, they can aggregate all their investments, make one capital call from their LPs and pay back the debt.

Technically, the difference of a few weeks doesn’t have an impact on returns, and are just a cash flow mechanism. But if those debt lines are drawn out longer, and longer, they could be used to artificially inflate returns. The debate of IRR, MOIC, and other benchmarking metrics for venture funds is a hot topic.

The Current North Star

So in a world where LPs have exposure to public equities that have plummeted, overvalued private companies, and real estate that is exposed to higher interest rates—what are people focused on?

LPs care about not losing money. VCs care about raising their next fund. The best thing for both parties in the capital allocation value chain is NOT speed. If VCs start aggressively calling capital, LPs may find themselves unable to come up with the cash to satisfy those capital calls. If VCs invest, and then the market takes longer to correct than expected, their returns could be lower.

So, does this mean venture capital is taking a couple years off? Definitely not. But what becomes more likely is an exacerbated bifurcation between companies that can and can't access capital.

The Bifurcation of Capital

Over a year ago, I wrote a piece called A Tale of Two Markets:

"There is a legitimate economic bifurcation between companies. This is happening in public and private markets where the divide among companies between the best and the rest is becoming more defined."

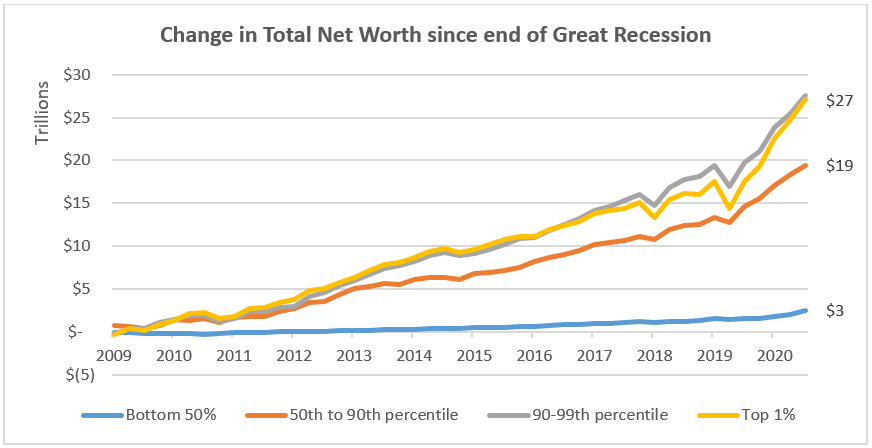

At the time, I talked mostly about valuations and how the best companies were being rewarded differently. But the same will increasingly be true of where venture capital is invested. Think about charts you've seen illustrating the growing wealth gap between individuals.

Now just apply that same dichotomy to private companies, and assume its like we're in ~2011-2012. The more pressure there is on capital, the less fluid it is, and the more dramatic people's expectations are for what kinds of companies will get capital.

The same dichotomy exists in public markets where some of the largest funds are largely invested in the largest market cap companies. You see this even in ESG funds, meant to drive yield by investing in climate-conscious stocks. The biggest positions? Amazon, Google, Apple.

What Does This Mean For Venture Capital?

In some ways, the increased pressure on capital allocation is a good thing. Hucksters, tourists, scam artists, and wanna-bes get washed out. When the going gets tough, the not-tough find other jobs.

But there are some not-so-great implications of this bifurcation. One thing I liked about the 2021 hype was the shift of power from VCs to founders. As that starts to correct, VCs can very easily retreat to what is "tried and true." Established repeat founders from groups similar to themselves.

The fear is that venture limitations will limit access to capital for people and companies that should be getting more capital, not less. Peter Pezaris, SVP of strategy and experience at New Relic, described venture this way:

“Venture capital simply cannot stay frozen for long, and we’ll see renewed investments by the end of 2023. The record amount of dry powder at VC funds must be deployed according to schedules and in search of returns for investors. The VC community is driven by rumors and groupthink. All it will take to unlock a furious wave of pent-up demand is one person investing and sparking everyone else’s fear of missing out.”

The easier it is for VCs to defer to "rumors and groupthink," the less likely they are to be innovative. And if there is one thing we need more of in venture, its thinking that is less like more of the same.

The most important takeaway? The same lesson as my 3-year old. Sometimes, neither the journey nor the destination are what we expect. It's dangerous to assume something like a gravitational onslaught of capital will alleviate some of the suffering for startups trying to raise money. Understanding the reality of a situation, and the incentives at work, is critical to making accurate predictions of a given market.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

The debate of IRR, MOIC, and other benchmarking metrics for venture funds is a hot topic indeed. Great article 👍🏼

Loved how you broke down the typical fund lifecycle for us