This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I remember being in high school in my English class where we were doing speech and debate. The topic had turned political and one person in particular was taking a very firm stance: "George W. Bush was the greatest president in American history."

This was in 2008, so the perspective of being lied into Iraq was well on record and, for whatever reason, basically every other person in that class in New Mexico was staunchly anti-Bush. Their counter-argument left little room for compromise. According to them, George W. Bush was, in fact, the worst president the US had ever had.

Back and forth. Back and forth. The discussion became increasingly more heated, with me largely staying quiet. Eventually, everyone’s rhetoric got so riddled with hyperbole that I couldn't see myself in either side's camp. Finally, I chimed in.

I pointed out, as best I could, any anecdotes I remembered from past presidents. Harding had an administration riddled with corruption, Hoover exacerbated the Great Depression, and a bunch of them fought to keep slavery around. Can we really say he was the worst president in US history?

The Bush defender latched onto my tact, immediately taking the exact opposite lesson from it. "Exactly, every President has been terrible. George W. Bush has been the best of all of them."

I then had to point out the other side of the coin. Jefferson bought us 2/3 of the country, Lincoln abolished slavery, FDR got us out of the Great Depression and through WWII, LBJ signed the Civil Rights Act. How can we say Bush is the greatest president?

Now, I'd like to say we all nodded our heads understandingly, smiling. Patting each other on the back, and chuckling at our shared reality. But instead, that was a largely ignored footnote in the heated discussion that our teacher had to eventually just shut down.

No one went away with their minds changed. And that inability to settle into a nuanced middle ground has stuck with me. Not just in politics, but in most things in life. Any staunch beliefs, one way or another, have messy middles filled with nuance that are probably closer to reality. Management, strategy, religion, marriage, sports. But most people feel deeply uncomfortable with nuance, and increasingly so. Given everything that's happened over the last week, politics just happen to be the clearest place where this aversion to nuance exists.

Politics Are Allergic To Nuance

Reflecting on this election, in particular, I appreciate more than ever how much the tribalistic political system we've built for ourselves has become incapable of dealing with nuance.

I talked last week about a TED Talk from Brené Brown, but funny enough I also read a book by her earlier this year called Braving The Wilderness, and this line struck me:

"Is there tension and vulnerability in supporting both [sides of a policy]? Hell, yes. It’s the wilderness. But most of the criticism comes from people who are intent on forcing these false either/or dichotomies and shaming us for not hating the right people. It’s definitely messier taking a nuanced stance, but it’s also critically important to true belonging."

Take President Trump's victory as the epitome of this forced "false either/or dichotomy." Democrats want you to believe that you either vote for Kamala Harris, or you're a racist / sexist / homophobe / xenophobe trash panda.

But now that Trump has won, you're seeing victory laps from Republicans that seem to assume universal acceptance of every stance Trump has ever taken. And some of the worst the Republican party has to offer, like Andrew Tate or Nick Fuentes, see it as a victory for their horrendous ideologies too. But the reality is that even the short list of people who helped get Trump elected have, themselves, expressed more nuanced perspectives on him.

JD Vance famously once described himself as a "Never Trump guy." Joe Rogan previously described Trump as "an existential threat to democracy." Elon Musk said in 2016 that Trump "wasn't the right man for the job" and in 2022 that Trump "shouldn't run again."

The thing that bothers me about politics is that people will try and deride this as flip-flopping. Granted, in many cases there is a "kiss the ring" attitude towards the potential pillars of power that breaks down the resolve of any conviction. But for many people, it represents a nuanced perspective. Do Vance, Rogan, and Musk love everything about Trump as a person? Or every position he has? No. But he represents the things that are most important to them. Its a nuanced and messy middle.

And we should be allowed to think nuanced things without being socially crucified for them. Another book I read this year is a biography on Mitt Romney where it talks about some of the things he got in trouble for saying on the campaign trail:

"The irony of all the candidates' aesthetic posturing and the media's focus on microscopic minutiae was that there were genuine, important ideological differences between the two men in the race. When Romney had told a group of hecklers at the Iowa State Fair that "corporations are people, my friend"-handing the Obama campaign a golden sound bite for future use-he'd really meant it. For all his complicated feelings about the broader conservative agenda, Romney was a committed capitalist. He believed the things he said in his speeches-that free enterprise was the most successful antidote to poverty in the history of the world, that federal policy should be designed to support existing businesses and help grow new ones, that the best government was one that made the lives of "job creators" as easy as possible. Everybody benefited from what they built."

We should be allowed to have these nuanced beliefs. "Corporations are people" being just one of thousands. For almost every political issue, I struggle with the nuanced middle:

On the one hand people say abortion should be the default available option any time with no limits. On the other hand people say it should never be accessible even when someone's life is at risk.

On the one hand people say anyone can be trans and should be able to have life-altering surgery at any point, at any age, regardless of parental consent. And if you don't call them their preferred pronouns, you're automatically a bigot. On the other hand, people say trans people shouldn't exist and should be completely ignored legally and socially.

On the one hand people think black people are in a worse position than they've ever been in US history and are the victims of the greatest injustice that ensures every black person will be disadvantaged in every aspect of life. On the other hand people think there is literally zero bias on the basis of race and everyone has the exact same opportunities.

On the one hand people think that any Latino people will and should identify with "illegal immigrants" and should be outraged by anything short of unfettered access to come into America. On the other hand people think "America is for Americans" and we should shut off the pipeline to anyone coming into the US that doesn't fit their standard of what an American should look like.

On the one hand people think the US is a villainous bastion of evil and they hate the country they live in, and everything it stands for internationally. On the other hand people believe America can literally do no wrong, and anything America would do is good because America is good.

But none of those are exactly right. Nuance. Nuance. Nuance.

Often I think about this idea of the importance of an informed electorate. People need to know what they care about and understand the nuance. The unfortunate reality is the 80% of the country has pre-selected their perspectives, which isn't great. For a huge swath of people, they will only ever vote Democrat and the other half that will only ever vote Republican.

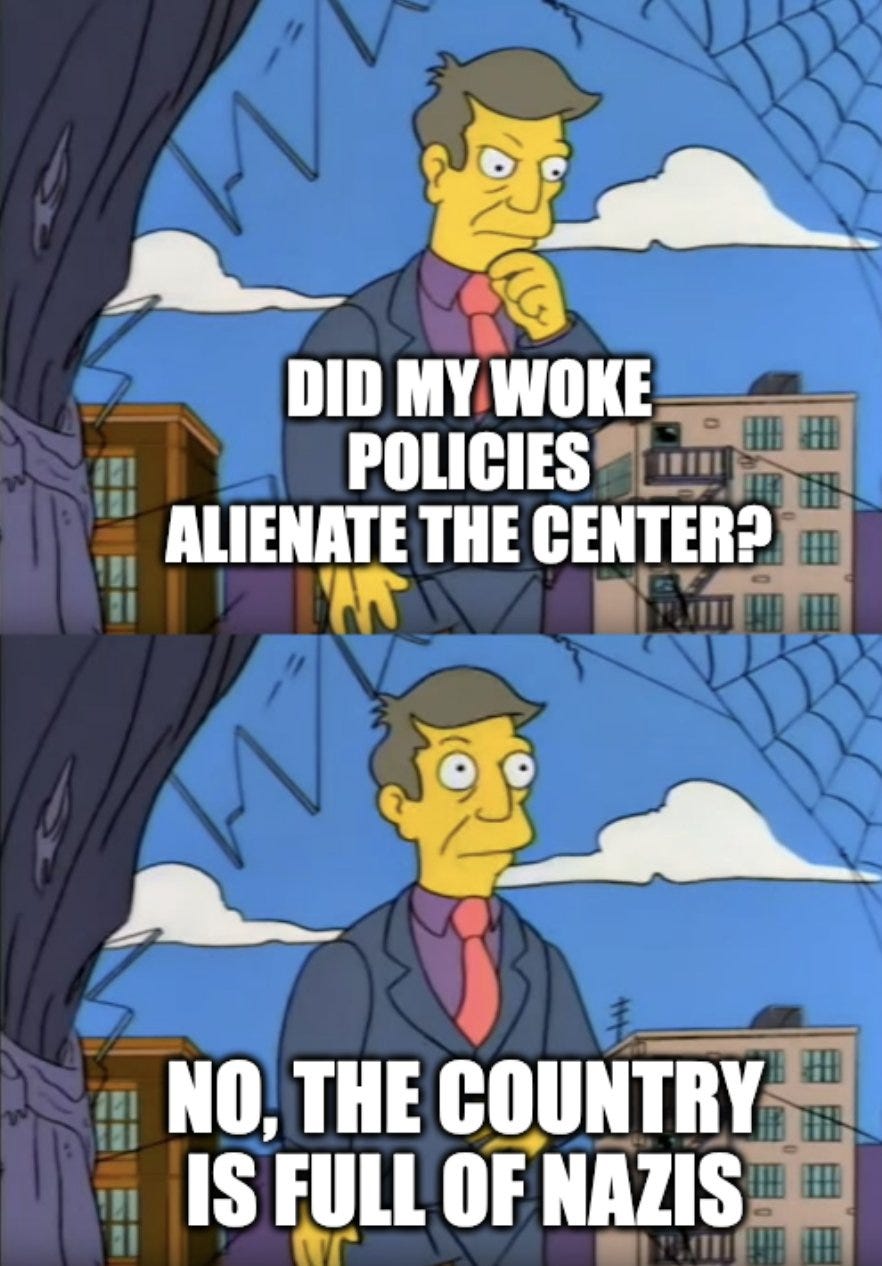

But the reason Democrats have been so humbled by this election is because of the 20% in the middle who are swayable. Some will dismiss the swaying as "the other side is more racist than I thought."

But, again, it's more nuanced than that. And BOY were the people in the middle swayed. Across basically every state and demographic. Those people who were swayed are the "informed electorate" that leveraged the engine to reflect their will. Thinking about this reminded me of a book, The Death of Expertise, that makes this point:

"Laypeople too easily forget that the republican form of government under which they live was not designed for mass decisions about complicated issues. Neither, of course, was it designed for rule by a tiny group of technocrats or experts. Rather, it was meant to be the vehicle by which an informed electorate—informed being the key word here—could choose other people to represent them and to make decisions on their behalf."

The mainstream media perspective would probably be that, "well, if we're talking about an electorate that isn't actually informed, it's Trump voters." But, again, the overwhelming swaying we saw towards Trump indicates more nuance than just "the dumb racists won again."

No, it’s true of everyone in the 80% I described. If you’ve already made up your mind, then you’re, by definition, not looking to be informed. I respect the 20% in the middle who were willing to be swayed, and I'll come back to them. But those 80% who are staunchly one way or another, they're failing to lean into the nuance. And it’s not entirely their fault. The messy middle of nuance is increasingly harder and harder to engage in.

Information: Velocity ➡️ Dissemination ➡️ Impact

A few months ago I had a great conversation with my colleague, Sachin Maini, who has an incredible background as an editor on some of the famous Nfx essays on network effects. In that conversation Sachin said, in effect:

"Information velocity is higher, and the rate of change in perspectives or information dissemination is a lot faster now. The rate of change in people's perspective is unprecedented. In prior times you could have entire generations share the same perspective without much changes."

There is so much information constantly swirling, trying to change our perspectives. What's more, the world has grown increasingly complicated. The average person no longer understands how their car / phone / computer / government works. So it can sometimes be easier to default to group beliefs and conspiracy theories.

When the SVB banking crisis happened, it happened at internet speed. The speed of the internet leaves very little time for nuanced discussions, especially of something as esoteric as a bank's balance sheet. Once again, The Death of Expertise made a great point in quoting Caitlin Dewey who "worried that fact-checking could never defeat myths and hoaxes because 'no one has the time or cognitive capacity to reason all the apparent nuances and discrepancies out.'“

Morgan Housel made the same point in The Psychology of Money:

"A mindset that can be paranoid and optimistic at the same time is hard to maintain, because seeing things as black or white takes less effort than accepting nuance. But you need short-term paranoia to keep you alive long enough to exploit long-term optimism."

His mention of having both a paranoid and optimistic mind reminded me of an F. Scott Fitzgerald quote I reference all the time, and one that I think is critical for anyone seeking to grow more comfortable with the messy middle of nuance.

A Test of First-Rate Intelligence

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function."

This quote, to me, perfectly captures the reality of nuance. Being able to hold two opposed ideas in your mind at the same time and still function. So here's some examples of that nuance in action.

I didn't vote for Trump. That's a bigger conversation about whether policies or character weighs more in your decision, but for me it came down to character. Romney described similarly in his biography: “you’re choosing between a terrible person and terrible policies.” I don't care for Donald Trump as a person, so I chose to NOT vote for the terrible person.

But I resonated with a video with Zachary Levi where he said, "I'm not voting for Donald Trump. I'm voting... for Elon Musk, and this team."

Now, I may not love the whole team. I'm a little nervous about RFK Jr. running the health department. But I like Elon Musk. A lot. Not as much as the people commenting on X anytime I mention $TSLA. But a lot.

And honestly, the idea of Elon Musk running a Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is quite compelling to me. I will watch that unfold with an almost giddy interest.

And I think a lot of people may have similar perspectives. They don't like Trump as a person, or many of the things he stands for. But they were willing to find the nuanced middle that made them feel comfortable with it. And more than the MAGA die hards, more than Kamala vibesters, I respect those in the nuanced middle.

Joe Rogan is probably the best and loudest example of this.

After Joe Rogan played a meaningful part in helping to push Trump over the edge, there were calls for liberals to "build their own Joe Rogan." But Ryan Broderick had a great thread on how that fundamentally misses the point of who Joe Rogan is.

Joe Rogan describes himself as "socially liberal, saying that he supports same-sex marriage, gay rights, women's rights, recreational drug use, universal health care, and universal basic income but also supports gun rights and the Second Amendment." He's previously vocally supported Bernie Sanders.

Ryan's thread points out that most of his audience is "normal men" who listen to him because "he's not embarrassed to ask guests questions that uninformed men are curious about." No one is more willing to embrace the nuance.

That’s the kind of nuance I respect, and want more of in my own thinking.

Building a "White Hot Core"

As I reflected on how better to embrace the nuance of the messy middle, I was met with a one-two punch of great writing this week. First, Packy McCormick's essay Read More Books. Second, an essay from Jack Raines called Ask Good Questions.

While thats the order I read the essays in, the one-two punch actually comes in reverse order. First, Jack frames an excellent perspective on how we should shape our first principles around asking the right questions:

"The internet commoditized information, and the widespread availability of information has devalued it because you can now find some data point, anecdote, or statistic to support any possible viewpoint, creating an environment ripe for echo chambers and false signals, which we saw this election cycle. To cut through those false signals, you have to be careful in deciding which information to look for. You have to ask good questions."

Finding the right questions to ask allows you to cut through the noise of partisan perspective and established attitudes. The partisan establishment is where nuance goes to die.

I've written before about how "group membership should be a lagging indicator of your beliefs, not a leading indicator." Asking the right questions is how you form those beliefs. Then, in Packy's piece you get a great playbook for building out your more nuanced perspective:

"Benchmark partner Sarah Tavel has this idea about building a “white hot core” when starting a marketplace. The idea is that you shouldn’t try to serve everyone at once, at the beginning, but should begin by nailing the product for a very specific, constrained problem or niche. Prioritize retention over growth. Then, and only then, once your small niche of users really loves your product, you can expand outward into adjacent niches and problems.

I’ve always been a little jealous of the way that it seems people like Byrne and Ben Thompson’s brains work. From the outside, it seems like they have a scaffolding in their brain, and then, whenever any new information comes in, they can simply hang it on that scaffolding. That’s why they can write five excellent essays a week when I struggle to write one.

I haven’t asked them about this, but what I think is actually happening – other than just raw horsepower – is something similar to Sarah’s white hot core idea.

Read a lot of high-quality stuff on a certain topic or time period. Recognize connections, reinforce them, prioritize retention over growth. Then, and only then, once your core is established, expand outward. It’s like constructing a map instead of dotting a bunch of dots."

'What do Republicans believe? or 'What do Democrats believe?' Those are bad questions. How should America approach immigration in a way that both lives up to the ideals of being city on a hill and ensures safety and prosperity? If guns are the leading cause of death for children, what should we do about that? Regardless of what the NRA wants.

And this goes beyond politics. Every position we seek to take we should be focused on asking the right questions and building a "white hot core" of knowledge. A latticework of thought around which to build a tapestry of perspective.

Embrace The Nuance

This year, I read the book Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver. I enjoyed it very much (and so did other people apparently, since it won her a Pulitzer.) The novel takes place in the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia. Broader Appalachia extends across Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and much of the Northeastern US.

The story is about a boy Damon Fields, but his nickname is Demon Copperhead because of his red hair and attitude. His experience extends across poverty, foster care, abuse, oxycontin, alcoholism, fentanyl, and relationships. If that sounds somewhat familiar, that's because it is many of the same themes in JD Vance's memoir, Hillbilly Elegy.

Kingsolver and Vance both grew up in Appalachia. They both saw a very specific culture that they wanted to capture. She used fiction, he used memoir.

But they represent very different perspectives. Many criticize Vance's book as "inauthentic," and trafficking in "ugly stereotypes and tropes." Kingsolver, herself, has expressed her disappointment with the book:

"He's entitled to write his memoir. But the fact that that got pitched and bought wholesale as my memoir too. The explanation of a people. [It] makes me so mad. Because he had no context. He didn't talk about structural poverty, he didn't talk about the history of this region. It was this bootstrapped story of ‘if you only work hard enough.’ What's heartbreaking about it is that it really validated the stereotype. It was so widely embraced by the rest of America because they want to hate on hillbillies. We are the last class of people that progressive people get to make fun of. A lot of us recognize structural racism, but structural classism is just not talked about."

Now, I liked Hillbilly Elegy. I read it in 2017. But I also did not grow up in rural poverty. So a lot of the imbalances that people like Barbara Kingsolver point out in criticism are fair. She a credible critic because of her lived experience.

I also really liked Demon Copperhead because it brought a raw and painful human experience to life for me in a way that made me empathize with the struggle and hopelessness.

On the one hand, JD Vance says that if you just work hard enough you can overcome these challenges of poverty and addiction. On the other hand, Barbara Kingsolver paints the story of why that isn't always the case. Why, in spite of your very best efforts, you will be meaningfully disadvantaged. And understanding that reality is a key aspect in helping improve anyone's situation.

The nuanced messy middle is that you can like Hillbilly Elegy and Demon Copperhead. You can believe that hard work can get people out of even the most hopeless situations. But you can also believe that it won't always work. You can believe in individual accountability AND the need for institution support of those whose individual capabilities won't be enough.

All of us could get more comfortable in that messy middle of nuance because, in my opinion, that's where the majority of truth resides.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Loved this post - clearly the work of a thoughtful and empathetic person. Turns out social scientist Dr Maryanne Wolf is weeping for the decline of deep reading - like the books you mention- because the process of reading books like that, especially deep reading in early childhood, is the scaffolding for empathy- and likely, the ability to hold opposable ideas and understand nuance.

Reading this was enlightening in and of itself. Regarding politics, the most difficult part was picking between good policy or good character. But I challenge everyone here to also look beyond what we've been told is bad character — plenty of people who have met Trump first-hand claims otherwise, and similar to the Bush anecdote at the start, he's neither the worst nor should media snippets define someone.