The Stories We Tell

I've never been a big sports fan. I played sports in high school but it was more of an angst-ridden sense of teenage responsibility born out of watching too many movies. I would tell my parents not to come to my games because I knew it was "so boring to watch."

When I was in college I got in a big argument with a friend whose entire identity revolved around his relationship with sports. And he made the first viable point that made me appreciate why people like sports. "It's the story. The story of hard work and difficult odds. Anyone can resonate with that."

When he said that I realized it was true. I loved sports movies. Everything from Remember the Titans to The Last Dance. What resonated the most was the story.

This extends to more than just sports. People have gone looking for stories elsewhere in places like public equity markets. We've seen an explosion of retail investors over the last few years. 15% of retail investors today got their start in 2020. Packy McCormick laid out this evolution perfectly in his piece, Business is the New Sports:

"The stock market is perfect [during quarantine] - on all day, the news cycle continues into the night, and if you follow it even casually, you never have to be bored. We treat our favorite companies more like our favorite teams, and our favorite business leaders more like our favorite athletes -- with all of the passion, frustration, and booing that implies."

The amount of consumer interest in business isn't just an interesting observation. It changes the way the "game" of business is played. Whether its how a valuation is determined (see "Meme Stocks") or how your marketing campaign just needs one meme-able moment and it’s nearly free. Companies have to adjust to the level of scrutiny and interest from the outside world. People become invested in the stories and then they become invested in how the game is played. The same thing is happening in venture capital.

The Story of Venture

When I started in venture in 2014 it was still a much more under-the-radar industry that few people talked about. The Social Network had only come out a few years before and Shark Tank wasn't much older. I've written before about the state of VC:

"Venture has been a cottage industry for decades with a lot of participants who believe themselves to be the protectors and deliverers of innovation while sitting on one of the most under-innovated models that exists."

While the majority of the broader venture market is still dominated by large traditional firms we're seeing more changes in the space than ever before. Celebrities are not only active angels but they're building firms whether its The Chainsmokers or Serena Williams.

Angel investing has exploded past $25B in capital invested and you're seeing a broader landscape of experienced operators investing in, and even leading rounds.

With more people aware of how venture works there has never been a better opportunity to step back and reevaluate how venture firms operate. There are a lot of firms reinventing themselves to better fit the ways the world is changing. It isn't just about paying high prices its figuring out how they'll differentiate themselves going forward.

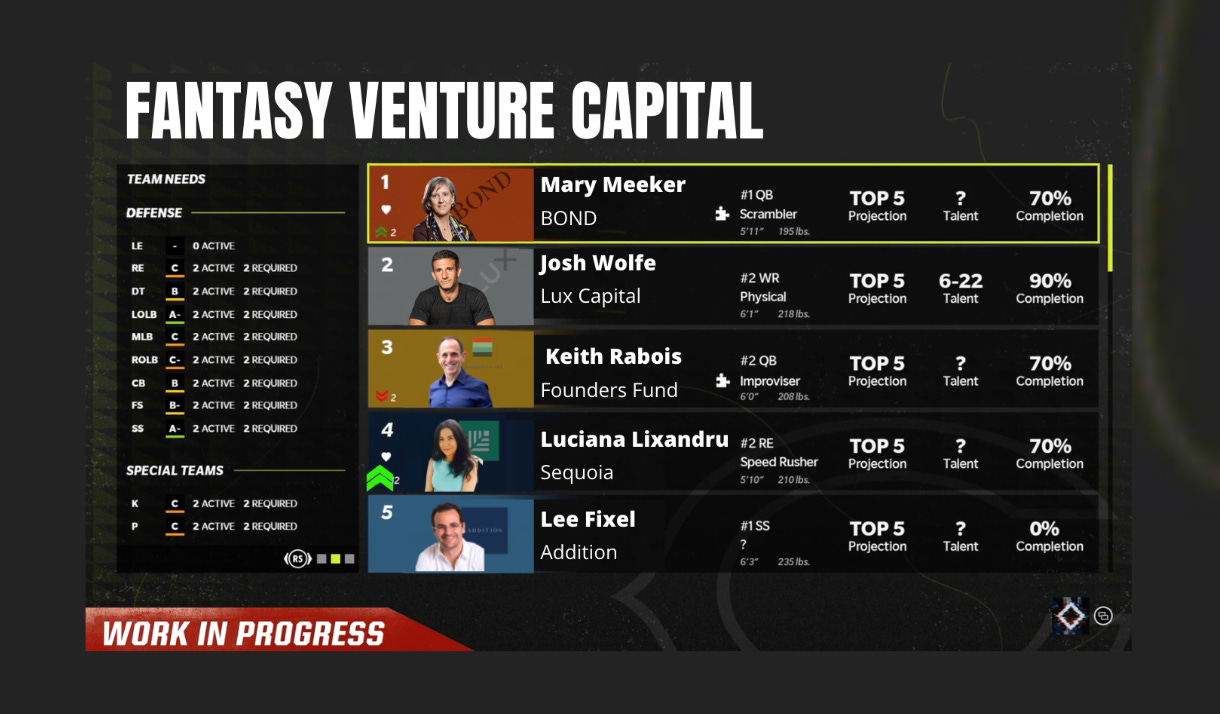

Over the last 6 months I've talked to over 100 different VCs at dozens of firms, many of them experiencing this change. I've written about some of these changes but I wanted play a game of "Fantasy Venture Capital" based on the 'dream scenarios' that some people have for the funds they work with and for.

Building a Better Venture Fund

Most venture firms have been around for decades and often have some symptoms of the innovator's dilemma where they struggle to innovate on their own model because it’s been working fine for them (until it's too late.) But what could a future-proof venture firm look like if it was built from scratch? These are the most common ideas that have come up in my conversations

Visionary leadership

An org chart that reflects value-creation

Product-led value proposition

Incentivizing collaboration and apprenticeship internally

Intellectually honest decision making

Like any good startup the most critical initial ingredients are the visionary founder and the initial team. So let's start there.

Visionary Leadership

The Fantasy: A visionary leader who clearly articulates the vision of the firm and works maniacally to bring that vision into reality through fundraising, hiring, and building the culture to collectively tackle that vision.

I've written before about the status quo among a lot of venture firms' General Partnerships:

"These partnerships were made up of mostly old white dudes and as far as the firm was concerned? They are God. They dictate every aspect of the strategy of the firm."

In a company there are a lot of drawbacks in having co-CEOs; imagine having 6+ CEOs. That's usually what it's like to work at a venture fund. When everyone is the leader? No one is.

When you look at some of the most successful venture funds they typically have a clear leader and that leader is the visionary tone-setter for the firm. Whether it's Marc Andreessen at a16z or Sequoia's recent leadership transition from Doug Leone to Roelof Botha.

This isn't about dictatorship. Social Capital is a great example of what happens to a venture firm when you have a dictator with all the control and limited vision. This is about people wanting to be led by someone who inspires them. I saw this over and over again when I wrote my piece on building talent vortexes into tech mafias.

Doug Leone made a clear point about leadership in a recent podcast: "The [leader's] job is to make the receptionist rich. If the [leader] makes the receptionist rich, then I guarantee everyone wins." You want a CEO whose vision is built around everyone being as successful as possible. Not every firm has a proper CEO but more of them could certainly use one.

Instead, what most venture firms have is a hot mess of internal politics where you often have to spend a good chunk of your time figuring out who has the power to get things done rather than pushing a shared vision forward. That lack of clarity around leadership trickles down into the org chart.

A Value-Based Org Chart

The Fantasy: An effective hierarchy that allows different "business lines" (investing, marketing, talent, IR) to control their own destiny while demonstrating the value they can contribute to the overall vision of the firm. There are no second-class citizens, only second-class ideas.

If there is one thing that I rant about more than anything its the uninspiring org chart that most venture firms have. Most venture firms are structured more like a loose collection of roaming wolf packs than any kind of proper organization.

A lack of clarity around the org chart creates problems for both investors and the talented people these firms have brought on to help their portfolio companies with things like recruiting, marketing, and business development. The closest analogy for what venture funds look like today would be a company run by a committee made up of the sales team (investing) who dictate the strategy to every other organization.

Firms like Paradigm are creating more effective org charts because they recognize that their value will come from being an effective organization with different strengths and they work to reward people accordingly. Someone who is world-class at talent should have just as much political sway as any investor. What you care about is the quality of the idea, the execution, and how it contributes to the overall vision of the firm. Not the political power of the person behind any of it.

Product-Led Value Proposition

The Fantasy: When anyone asks the question 'how is your firm different?' you have a clear answer and can point to specific aspects of the firm that demonstrate that unique difference. You can describe what "product" you offer for founders that addresses a particular 'job-to-be-done' even if that product isn't for everyone.

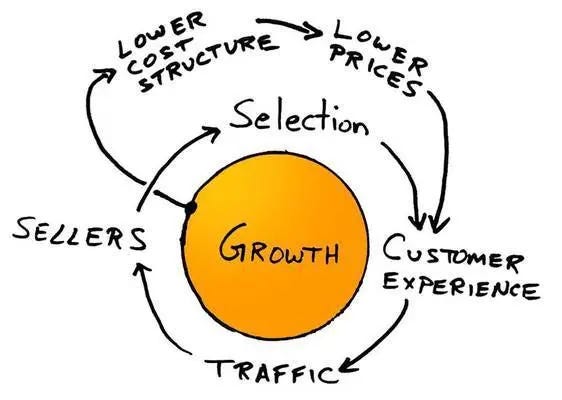

When I worked at Amazon we would print an image of the "Amazon Flywheel" on the front of every presentation we handed out. Legend tells the tale of Father Bezos etching it on to a dinner napkin in a fever dream of innovation.

Very few venture firms have a similar flywheel. They may have a funnel. And they may have aspects of what they do that feeds that funnel. But the problem with a funnel is it isn't self-perpetuating. A flywheel feeds itself.

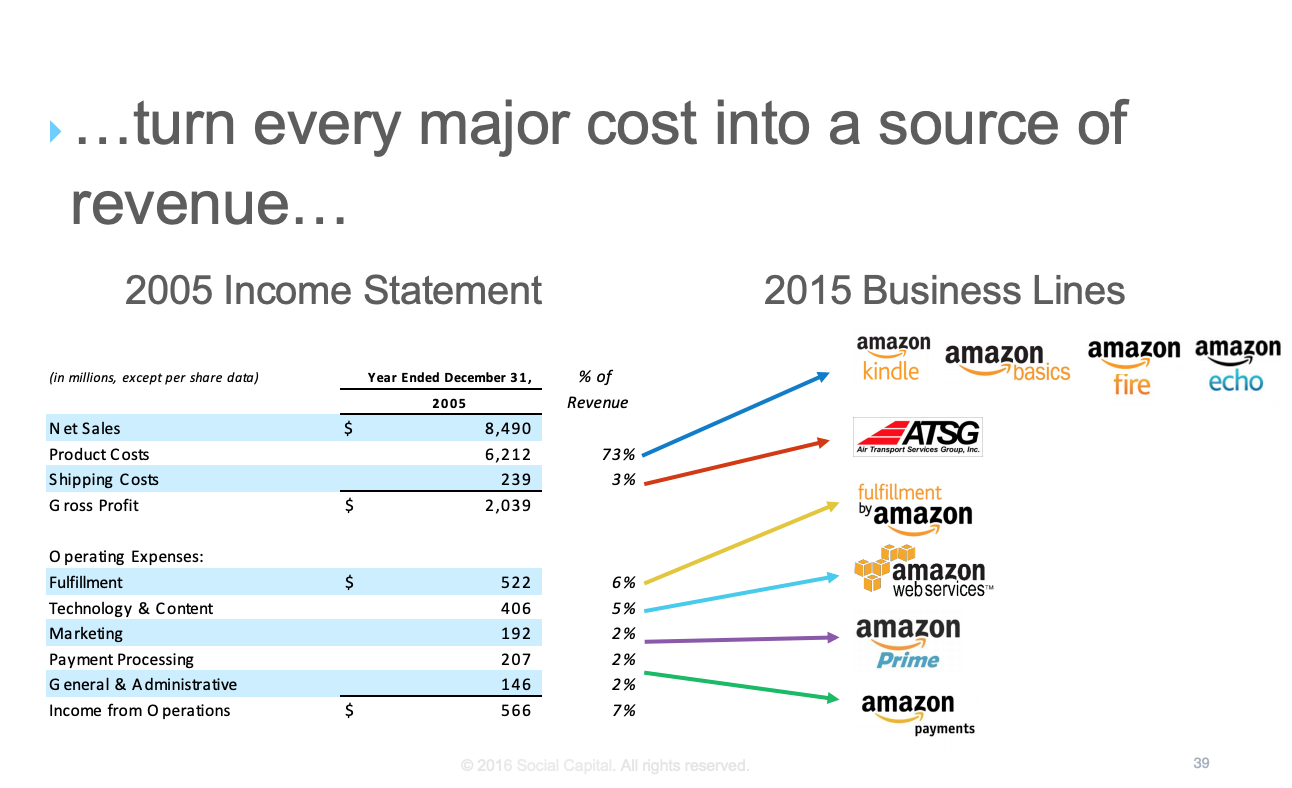

What, if anything, in a venture fund gives them leverage beyond their brand? There aren't many better examples of creating leverage than Amazon. They've built a collection of businesses out of leveraging their own needs internally.

Think about a P&L of a venture firm. The vast majority of what you pay for is headcount and swag. None of that creates any sustainable asset. One prominent crossover investor described the way venture funds think about firm building this way:

"For most of them everything is COGS. They just burn oil at what they need right now without really thinking about how it will last. Very few venture firms are investing in R&D."

The venture fund that most people want to work for is one that recognizes the expense in building a fund and finds a way to turn that into their unique product flywheel. What do you do as a firm? And how do you ensure that you get more and more effective at it over time? This is becoming more and more common as investors acknowledge the need for that clearly articulated product vision.

The vision presented by that visionary CEO? That is the product-led flywheel. When you can articulate what product your firm offers you can align everyones incentives not just around "doing deals," but around contributing to that flywheel.

Incentivizing Collaboration and Apprenticeship Internally

The Fantasy: Everyone's incentives are tied to contributing to the overall product flywheel of the firm making it easier to collaborate and support each other vs. competing for a single metric, like "eating what you kill."

In a venture firm internal political power comes from "getting deals done." When the main currency for the culture is getting credit for making investments it aligns every activity around deploying capital and judges it against that bar. That's one of the reasons other functional areas in a firm (talent, BD) are second-class citizens. If you can't directly correlate your contribution to "deals done" then your value is unclear. This would be like “closing a sale” being the only way anyone at a company can gain political power. Makes it real tough for engineering or marketing.

That "eat what you kill" lone-wolf culture exists in most venture funds. And its exacerbated by the emphasis most firms on specific deal-makers. A lot of VCs would prefer to work in an effective team that can all trust each other and contribute to exceptional success.

But the sad reality of venture is that most investors struggle to trust each other. There is so much effort required to ensure you get credit for as much as possible that you always have to be hesitant of folks that might take any of your credit. I've written before about the struggle that venture firms face in trusting each other internally:

"No one trusts each other and you don't know how to sort through people. So you let these people prove themselves until you trust them. And you usually don't really trust them until you've already established your own career. Trust is a luxury."

This may seem like an exaggeration but deal-specific judgements are frequent in venture firms. A lot of investors have a story of when a senior partner came to them about a deal they weren't happy about doing to say something to the effect of, "If this deal doesn't work out? You're fired."

That's not apprenticeship or collaboration. That's a recipe to breed risk aversion, which is ironic for a group of people meant to be taking on risks. But risk-aversion is rampant not only in the way VCs think about investments but also about their own people internally. They way you build a killer organization is keep a high bar when recruiting and then establish resources to help make those people better.

Because of the focus on the "eat what you kill" metric there is very little time or energy devoted to actual apprenticeship in venture. When you're aligned around a shared vision you recognize the value in building people up to more effectively contribute to that vision.

Intellectually Honest Decision Making

The Fantasy: Making decisions represent an intellectual exercise with honest ways of consistently evaluating investment opportunities and then frequently reflecting on decisions. 'Why did we get XYZ wrong?' There is no hiding your head in the sand when things go wrong. There is always an honest accounting of how decision-making can be better.

There is no complaint that I hear more frequently than the reactive decision making that most VCs fall victim to. They react out of FOMO and recency bias rather than long-term thinking. That complaint comes both from people working at venture firms and even founders (which is pretty embarrassing when you think about it.)

People often make the joke that investors think every company is a mediocre piece of vaporware that is dramatically over-valued, but their own investments represent conviction-driven bets in generational companies. But this translates into real behavior.

I've seen it play out so many times when an investor evaluates two different businesses with similar dynamics (e.g. growing, but questionably big markets). When it's their company? "We believe in the massive tailwinds." When it's someone else's company? "The market just isn't big enough to sustain a big company."

Without a framework for evaluating their own heuristics investors are left to gut-ridden guesswork. Once you have an organization that is led by a visionary leader, effectively incentivizing their team, and focusing their efforts around driving value through a clearly articulated product strategy you just won't abide crappy decision making.

A culture of evaluating the good and bad decisions a group has made is a natural result of an effectively crafted organization. And the rampant lack of that reflective culture among most VCs is indicative of the shoddy organization most of them have.

Lets Be Better

For some reason I think about this tweet from Mike Solana all the time. When I have conversations with VCs and I hear the frustration a lot of them have I bring this up. “I just want us all to be amazing.” Most of us want to better than FOMO-driven heat-seekers (at least I think so.)

Take the opportunity to reflect on these "dream the dream" fantasies that other VCs keep pointing out. And then see if we can't be better at what we do by making some of them a reality.