This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of investing in public and private tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

This is an exciting day for me! When I joined a new job a few years ago I met my new office mate Rex Woodbury He’s not only one of the most thoughtful and enjoyable people I know, but he was also one of the biggest inspirations for me to start writing more consistently. Rex writes a phenomenal weekly newsletter called Digital Native and it’s my go-to node on all things culture and internet trends. Couldn’t be more excited to blend our styles of macro and micro thinking in my first collaborative writing experiment.

We’re going to consider the question of how the current market downturn affects startups in 2022 and, more fundamentally, how does the “Everyone Is An Investor” trend hold up in a bear market?

This post originally appeared yesterday in Digital Native and I’m excited to share it here with all my favorite internet friends (and my Mom.)

Grabbing the Bear by the Horns

The bear came before the bull.

There’s an old proverb that goes, “It’s not wise to sell the bear’s skin before one has caught the bear.” In the 1700s, stemming from this proverb, the word “bear” began to refer to a speculator who sold stock. A “bear” would sell a borrowed stock with a delivery date specified in the future. The expectation was that prices would go down and the stock would be bought back at a lower price, with the bear keeping the difference as profit. A bear market thus came to signify a market in which prices were expected to drop.

But the bear needed a worthy opponent. In the 1700s, bears and bulls were widely considered opposites because of the once-popular blood sport of bull-and-bear fights (yup, it was a thing), so the term “bull market” came to signify a market in which prices are expected to rise. (Some people contend that the names also derive from how the animals fight: bears tend to swipe down, while bulls thrust up their horns.)

Many active investors today have never lived through a bear market; for all our professional lives, we’ve been blessed with a tremendous bull market. That’s changed this year, and it’s changed quickly. This abrupt shift is coinciding with the trend of everyone becoming an investor and everything becoming investable. The bear market and the investing boom are on a collision course, and the goal of this piece is to examine what the aftershocks will be.

Meet: Generation Investor

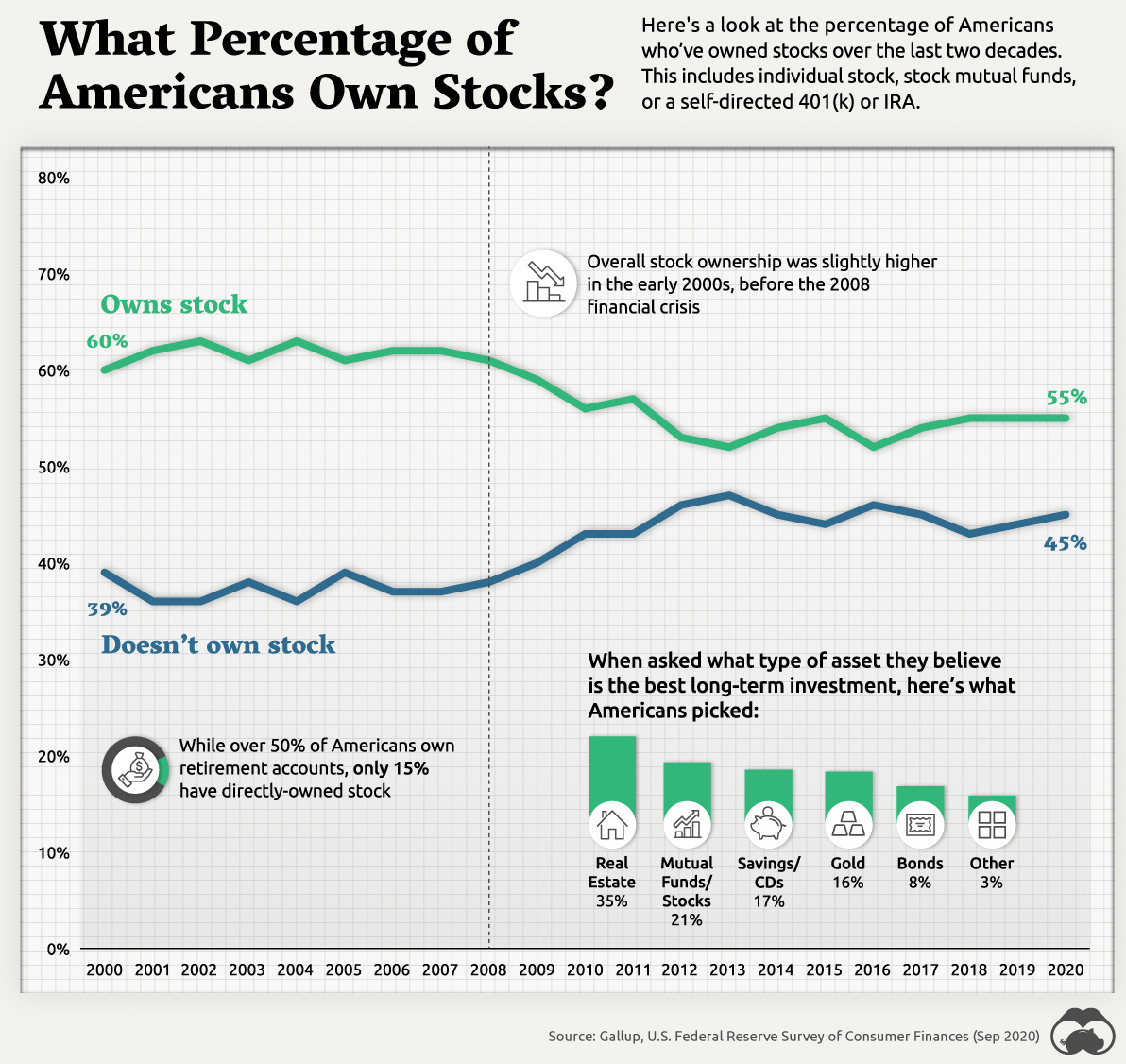

A dirty little secret of the stock market is that not many people take part in it. Only 15% of Americans directly own stock. If you count exposure through retirement accounts, that expands to a little over 50%. That figure has actually declined in recent years, sliding about five percentage points since the 2008 financial crisis.

Why does this matter? Owning stock is directly correlated with wealth creation. It’s difficult (maybe impossible) to reach the upper echelons of net worth on salary or hourly wages alone. As a result, the demographic most benefiting from the stock market—old white people—is the demographic that wields the most social and economic power in America. Baby Boomers hold 55% of stocks, valued at $22 trillion; Millennials own 2.5%, valued at $1 trillion. White Americans own a staggering 90% of stocks, with the average white investor owning 3x as much stock as the average Black or Hispanic investor.

And wealth begets wealth. Only 15% of families in the bottom 20% of income earners hold stock, while 92% of families in the top 10% of the income distribution own stock. The top 10% of income earners own 10 times as much of the stock market as the bottom 60%.

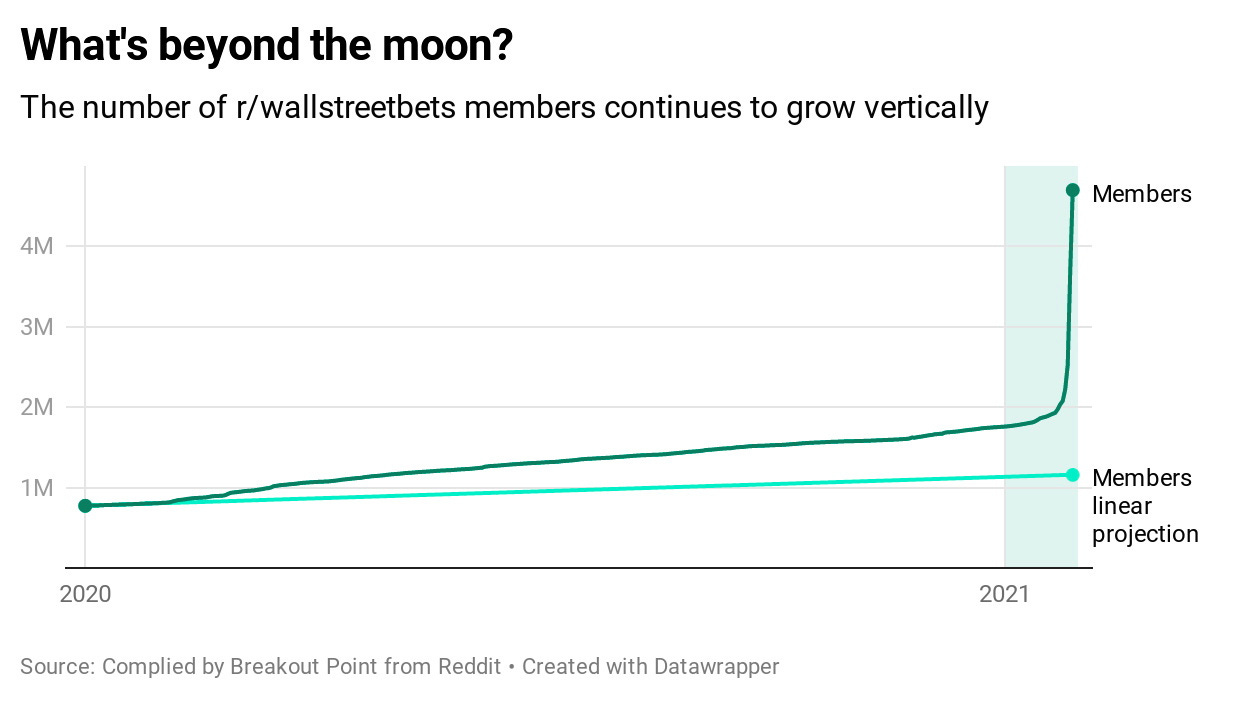

Skewed exposure to equity markets is a leading contributor to income inequality in America. This is what makes the recent boom in retail investing so exciting: 15% of the retail investors active today got their start in 2020. We saw this surge in the meme stock mania of 2021 and in the staggering growth of communities like r/WallStreetBets (now at 12.2 million members).

The emerging group of young investors has been called “Generation Investor” and they’re unlike any generation we’ve seen before. A NASDAQ survey found that 48% of Gen Z investors check their portfolios multiple times a day, while 24% check once a day. That compares to 39% and 22% for Millennials, 16% and 19% for Gen X, and 10% and 12% for Baby Boomers. Generation Investor is also more active: 34% of Gen Zs make trades a few times a week, compared to 26% of Millennials, 19% of Gen Xers, and 7% of Baby Boomers.

In a country in which only 14 states mandate financial literacy education in high school (no wonder people don’t know how to participate in the stock market), Gen Z turns to the internet: 91% report using social media for investing research. This has led to the rise of “FinTok” and “FinTwit”, the vibrant corners of TikTok and Twitter dedicated to analyzing the markets.

Of course, Generation Investor has come of age in the bull years of the past decade, and particularly in the frothy post-COVID markets. Now, the markets are in free-fall.

What’s Happening?

Members of Generation Investor have never experienced a bear market. For as long as they’ve been investing, everything has been up and to the right. (This also applies to many investors in the venture capital world—including us.) The last bear market was over a decade ago, when many of today’s investors were more preoccupied with prom dates, AP courses, and the Common App. The last time the S&P 500 ended the year down more than a few percent, Juno was in theaters, American Idol was the biggest show on TV (still with Simon, Randy, and Paula!), and we were all singing “Apple bottom jeans, boots with the fur.”

Year-to-date, the S&P is down 13%. Tech stocks have been hit particularly hard. The list of companies that have seen their valuations plummet is long, and the past few months have been especially punishing for companies that enjoyed a COVID boost: Peloton is down 91% from its high, Zoom is down 83%, and Shopify is down 79%.

In recent years, the market put a massive premium on growth: the companies that were growing the fastest often got the highest valuations. With a torrid pace of money printing in the US, that emphasis only increased; there was always cheap money around, so why turn a profit when you could pour cheap fuel into a growth engine?

But that calculus started to change as the Fed began to increase rates (effectively increasing the cost of capital). As interest rates go up, tech stocks will always go down. This is a basic principle: the value of tech stocks often lies in the promise of future earnings, and the time value of money changes with higher interest rates. (Remember that discounting math you learned in Econ 101?)

This new environment places more importance on companies that can turn a profit. Whereas high-growth stocks have plummeted in value (see: table above), companies with meaningful profitability like Apple, Google, and Microsoft have only seen ~20% drops from their highs.

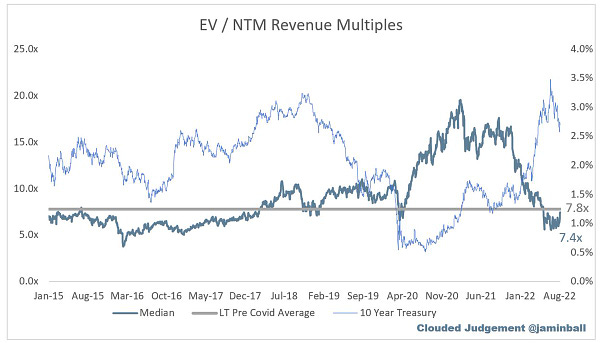

After skyrocketing to a 74x forward revenue multiple in November 2021, the top five software stocks have dropped to 18x forward revenue. The median forward revenue multiple across all software companies has even dipped below the pre-COVID average. That’s starting to come back a bit, but we’re not out of the woods yet.

A lot of people might point to venture capital as a safe haven from the manic mark-to-market of the public markets. After all, venture investments often have a five or 10 year horizon; venture is about the long game, not day-to-day, month-to-month, or even year-to-year swings. But there are plenty of trickle-down effects to venture funding. There’s a generation of VCs who justified a $1B+ valuation for a company by pointing to companies like Monday.com and Asana sitting at $19B and $26B valuations, respectively. But what happens when those companies drop back down to Earth at $6.4B and $4.6B? Paper mark-ups start to look a lot less assured.

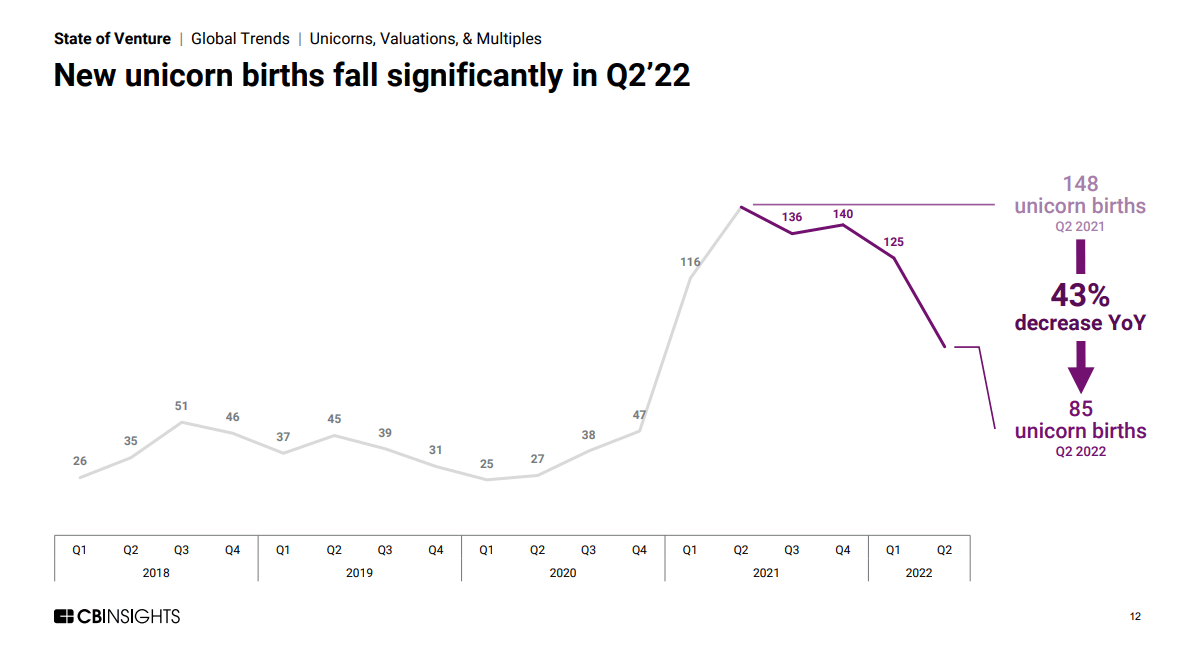

Venture investors aren’t only reevaluating valuations because they’re worried about their 401K. Assuming public market valuations (that ~7x forward revenue multiple Jamin talked about) don’t change dramatically in the next 5ish years, a lot of companies will struggle to make a return on their unicorn valuations. In Q2 2021, we saw 148 new unicorn valuations (!). In Q2 2022, that figure dropped by 43%.

Some (many) venture-backed companies will be fine. They’ll launch new products, they’ll expand to new geographies, they’ll generate more and more revenue. They’ll eventually grow into their valuations. But that isn’t the case for everyone. Index’s Mark Goldberg shares Dropbox’s story:

Since that tweet, Dropbox has dropped by another billion in market cap. Appreciating what something can eventually be worth is a critical piece of the investing equation. In the past few years, price discipline wasn’t always there, and there will be a lot of fallout in the years to come.

So does that mean investing is dead? Of course not.

The Night Is Darkest Just Before the Dawn

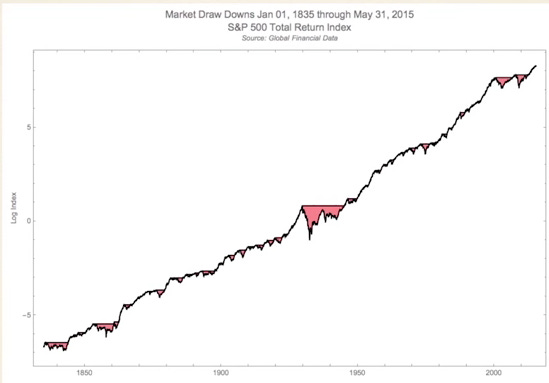

If there’s one consistent thing about investing, it’s risk. Investing is all about risk vs. reward. The only reason that there’s a return from investing (a reward) is because there was a risk that things could go wrong. Pain, meanwhile, is all a function of perspective. The longer the time horizon you look at, the more perspective you have. Zoom out to the last 180 years or so…

For decades and decades, the stock market has reliably trended up despite some extended periods of pain (the Great Depression, the Dotcom Bust, the Great Recession). We haven’t seen a catchy name yet applied to our current downturn, but rest assured that one will come.

When you look at the historical trends, the unfortunate reality is that this downturn could last a while. But luckily, we’ve been getting better at handling recessions. In early American history, it felt like you had a recession every time you had to replace your phonograph—1785, 1789, 1792, and on and on. What’s more, recessions would last 3 years, 4 years, 5 years. But since World War II, we’ve had only 13 recessions and the longest was the 2008 Great Recession at just 18 months.

This isn’t to belittle anyone’s pain. Economic downturns cost retirements, college tuitions, and livelihoods. There’s nothing fun about a market like the one we’re in. But when you zoom out, you start to appreciate how history has bent towards optimism.

One thing to be cautious of: market bounces. One (slightly morbid) way to describe a market bounce is the old saying, “Even a dead cat will bounce if dropped from high enough.” A Dead Cat Bounce has come to mean a fake-out in which you think the market is finally looking up, before it drops out from under you once again. For example, compare the markets from 2000, 2008, and today.

It’s safe to say that our recent rallies—like July’s uptick—are part of a long and gradual slide downward. In this chart, zoom in on the last few months and you see a lot of blues heading up before you catch some reds again:

The bigger takeaway from balancing optimism with a recessionary market is an adage we’ve heard many times from our P.E. teachers: short-term pain leads to long-term gain. For those privileged enough to remain long-term holders, being an investor will (eventually) pay off. The opportunity for everyone to be an investor already exists; the ability to be a successful investor in this market will require more thoughtfulness and discipline than in the market of the past few years.

Fortune Favors The Brave (and the Patient)

In a Crypto.com ad last October, Matt Damon declared, “Fortune favors the brave.” Since that commercial aired, Bitcoin has dropped more than 60%. Ouch.

Everyone from Tom Brady to Reese Witherspoon to Mike Tyson is in hot water for pumping crypto at the top of a bull market. And that makes an important point: this piece isn’t investment advice. None of us know what the market will look like tomorrow, much less five years from now. But there are some key principles that stand the test of time, like being patient and being diversified.

The opportunity that exists right now for every investor might feel relatively boring compared to the fervor of the last few years. Napoleon’s definition of a military genius was “the [person] who can do the average thing when everyone else around [them] is losing [their] mind.”

Plenty of people are losing their minds right now. But that isn’t new; plenty of people weren’t exactly in their right mind the last few years either. Everyone has stories of their neighbor’s nephew’s cousin who got in on the right token or the right stock at the perfect moment and was up 1,000%. But more often than not, the quickest returns are also the most speculative. High risk and high reward.

Instead, what we’re talking about is the opportunity to invest in generational assets that can genuinely stand the test of time. Here’s a story in three charts.

Chart #1: Apple from 1982 to 2000

From the time Apple went public in 1982 up through 2000, it was a fairly consistent company—always worth ~$8B give or take. In the run-up of the Dotcom, they shot up to be worth $22B.

Chart #2: Apple from 2000 to 2003

After the Dotcom Bust, Apple quickly plummeted further than that steady ~$8B, falling to a valuation as low as $4B and fluctuating up and down for a few years.

Chart #3: Apple from 2003 to Today

You know how the story ends. After watching a company plummet from $22B to $4B, you’d have to have a strong stomach to hang on for another 20 years. But for those who did? From that $4B low-point, Apple has swelled over 600x (!) to be worth $2.5 trillion. If you put $10,000 in Apple at its 2004 lows, you’d have $6,650,000 today.

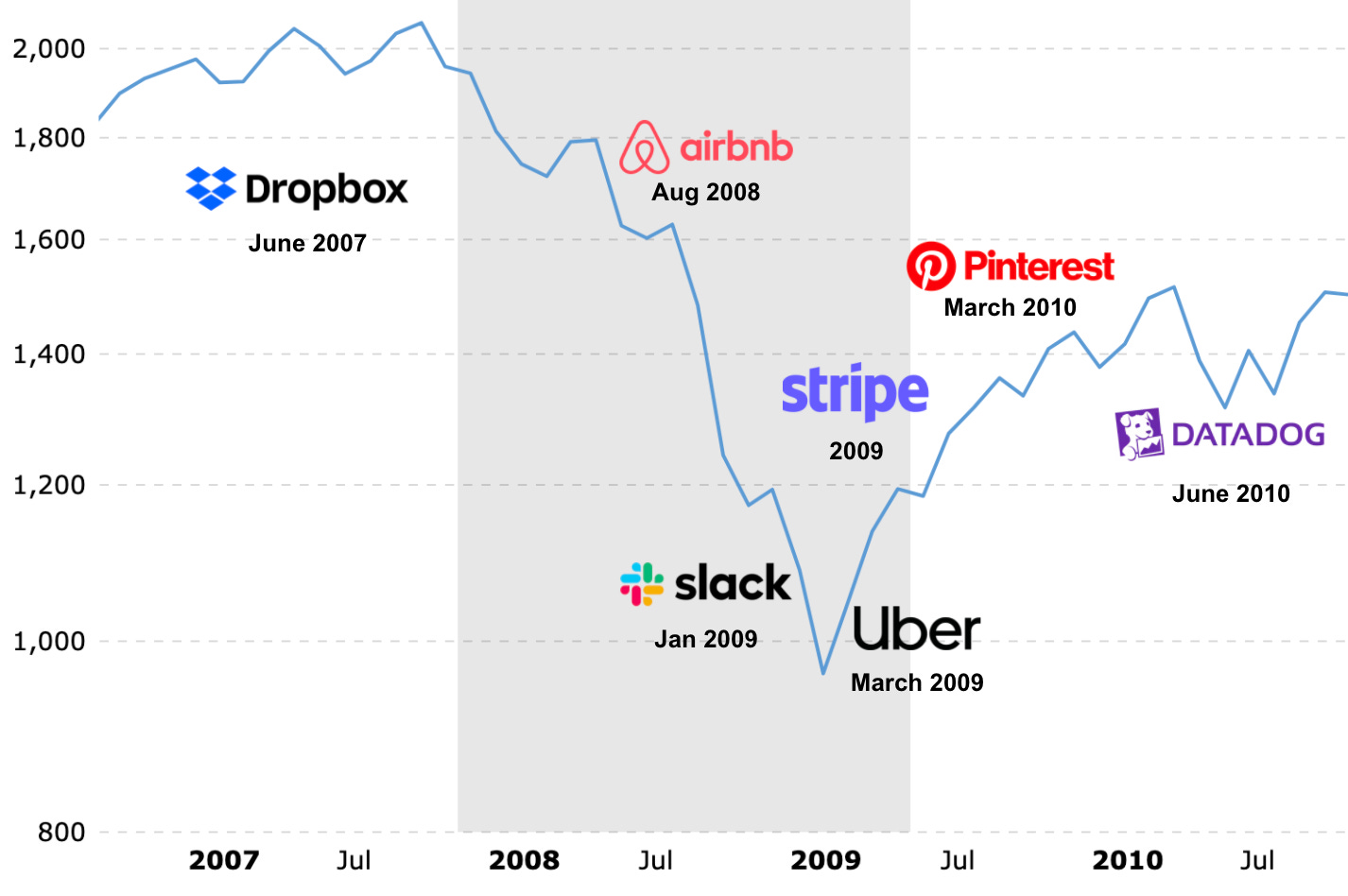

One important caveat: very few companies will be Apple. Or Google. Or Amazon. But a few will. And with a combination of thoughtfulness, research, and a lot of luck you can take a crack at investing in the next generation of phenomenal assets. The same is true of private companies. Some of the best venture-backed companies of the last decade came out of the Great Recession: Stripe, Uber, Airbnb.

The years of 2022, 2023, and 2024 might go down as the most formative of many venture capitalists’ lifetimes, with new iconic companies being created during the downturn. The key is to remain focused and to never stop investing. (To paraphrase Sequoia’s Don Valentine: “We’re in the business of investing, not not investing.”) For retail investors in the public markets, there might be an “Apple at $4B” opportunity out there; the key part is staying patient and picking the right horse.

As great as that 600x bagger on Apple was, it took a long time to compound. Investing in a company like Microsoft can be a generational opportunity. But take a look at the patience that generational investment would have required: over 16 years just to breakeven!

Investing is about patience and compounding over a long time horizon.

Everyone Is (Still) an Investor

In the 2010s, it became easier to invest. Investing came to mobile, with just a few taps on a phone to buy or sell a stock. Startups popularized no-fee trading, lowering cost barriers. A skepticism of “traditional” jobs bred by the Great Recession, Occupy Wall Street, and rising populism led to an interest in determining one’s own financial future, which in turn led to a generational mindset shift to thinking like an investor.

At the same time, there have become more options of what you can invest in. Here are examples of private startups that let you invest in various assets:

With Public, you can invest in stocks

With Dub, you can invest in an investment strategy

With Alt, you can invest in sports cards

With Masterworks, you can invest in fine art

With Fractional, you can invest in fractions of NFTs

With EquityBee, you can invest in startup equity

With Rally, you can invest in a person

With a different Rally, you can invest in collectibles

The list goes on. Of course, a key question here is: which of these assets are securities? The SEC is already going after many investing platforms, and as everything becomes a potential investment, more targets are sure to come.

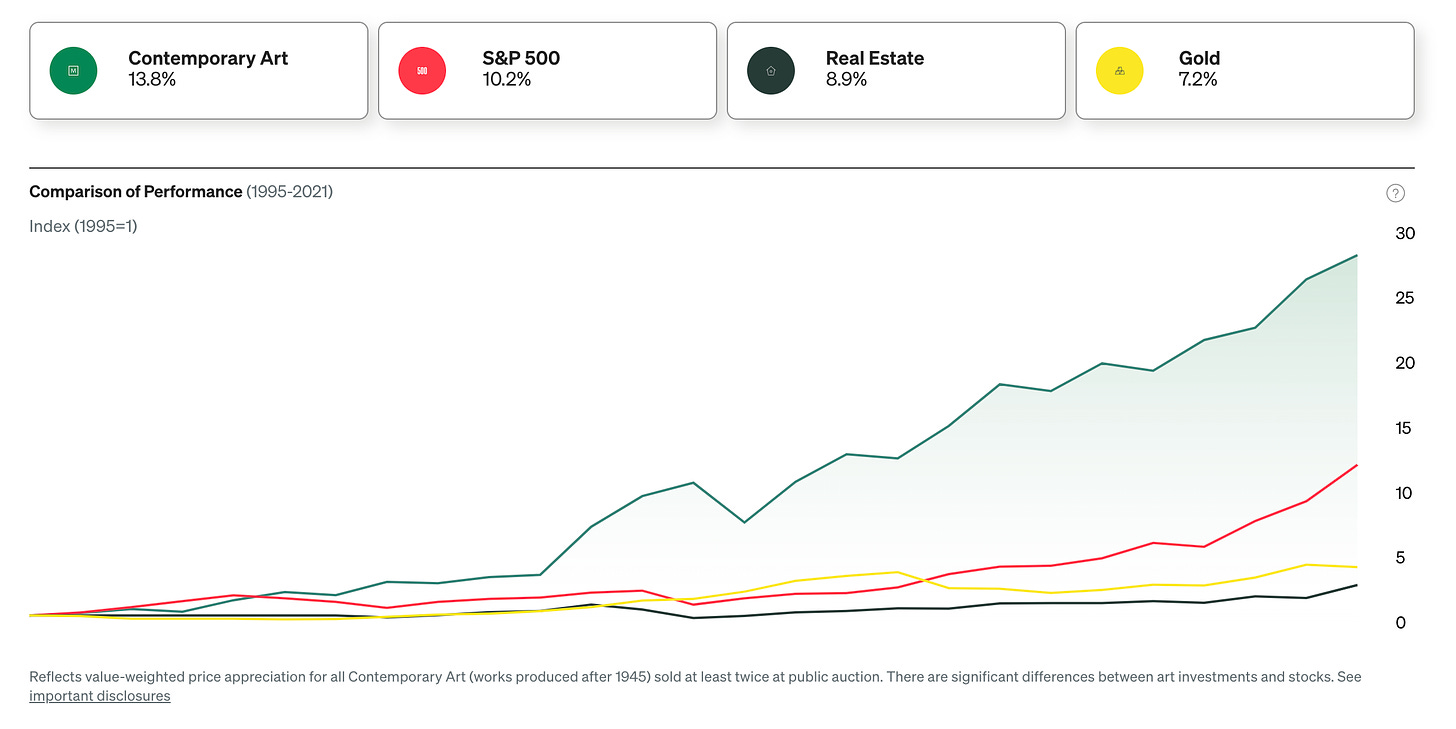

But this a fascinating shift because, for the first time, new asset classes are available as wealth-creating opportunities for more people. Take Masterworks, which argues that the fine art market boasts better returns than the stock market:

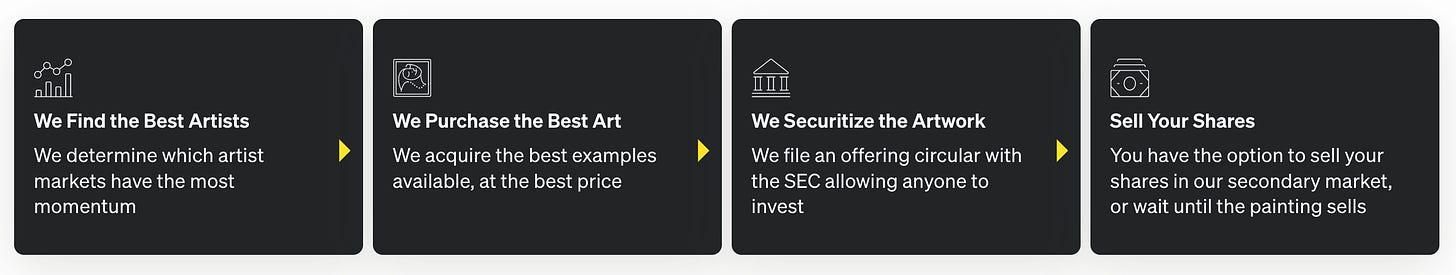

Masterworks buys art directly, then securitizes that art and sells shares in it.

If you can’t shell out hundreds of thousands for a Warhol or Banksy, you can buy a share of one and potentially earn double-digit annual returns:

The risk-reward calculus differs greatly among all of the various asset classes outlined above. And, of course, nothing should replace thorough research, patience, and above all, diversification in one’s portfolio.

But the gist is: now is still an exciting time to be an investor. Investing has never been more accessible, more social, more important. Investing is a critical path to real wealth creation, too often inaccessible or arcane in the past. There’s now a rising class of investors, more engaged than any generation before, and there are more opportunities to invest than ever before, with new platforms and technologies making nearly everything a potential investment. Even in a bear market, these things hold true. A bear market demands more discipline than was required in the frothy past few years, but it doesn’t change the long-term arc toward optimism and opportunity.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

I agree there's never been a better time to be an investor. Yet, I need to balance my optimism for financial markets with my experience selling and structuring derivatives and alternative products. All those new startups are a wonderful way to sell high margin products, but do they really benefit investors?