This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In many ways, I feel extremely blessed. The title of this piece comes from Psalm 23 as an expression of gratitude. But the term came to mind when it came to grappling with the overwhelming flow of constant information.

I've heard several variations of this idea: "we’re now exposed to as much data in a single day as someone in the 15th century would be in their entire lifetime." We read more than people ever read. We interact with more people than anyone would have ever met before. Despite Dunbar's number, I don't need to maintain a stable social relationship with everyone on the internet who still gets to live rent-free in my head.

All those books, movies, shows, tweets, podcasts, talks, YouTube videos, emails, and random interactions fill our heads with information, for better or for worse.

And the volume is only going to increase exponentially. Every AI pitch emphasizes this idea of "augmenting human capability." And, in many ways, those capabilities will enable users to sift through the noise to identify the signal more effectively. But in most non-structured use cases, there will still be a need for human capability when it comes to determining what to listen to (i.e. tastemaking). And on top of that, a ton of the use cases for AI are generative, meaning the volume of text and videos and information is only going to increase at an effective zero marginal cost.

When it comes to any attempt at garnering a clear, well-articulated insight from the mountains of information I'm exposed to, I often feel like I’m chasing a single butterfly in an ocean of fluttering wings, and I can’t quite grasp it.

That feeling of grasping at something I can't quite get my hands on leaves me thinking about this T.S. Eliot quote at least once a week:

"Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?"

This felt especially acute after finishing my first week of paternity leave where I wasn't tracking the news as closely, or funding announcements, or product releases, and when I sat down to catch up I realized that in my normal week, I was already just barely keeping my head above water.

So I set out to ponder the question of how I can better capture that information. Luckily, I'm evolving as a person so my conclusion wasn't a new note taking system. Instead, I landed on an idea I've been revolving around for a while since I wrote a piece called "The Inescapable Debate of Human Nature". In it, I said "Group membership should be a lagging indicator of your beliefs, not a leading indicator."

An important logical assumption from that is that before you can act, or decide anything, or join a group, you have to have beliefs. And too often, as I said in that piece on human nature, "When people substitute their own value system with a cookie-cutter platform from their in-group the first thing to die is nuance." So, instead of leaning on group membership, or group think more generally, for your beliefs, you should, instead, pursue the acquisition of wisdom that will shape your beliefs. Then, you can act on it.

The Moral Obligation of Wisdom Acquisition

I've referenced that T.S. Eliot quote enough times in my life that, when I turned back to each reference in my notes, I came across a collection of other related quotes, all of which start to form a picture of something that is not just a nice to have, but a moral obligation. The first, and clearest, comes from a reference to Confucius used in a talk by Charlie Munger:

"The acquisition of wisdom is a moral duty. It's not something you do just to advance in life. And there's a corollary to that idea that is very important. It requires that you're hooked on lifetime learning. Without lifetime learning, you people are not going to do very well. You are not going to get very far in life based on what you already know. You're going to advance in life by what you learn after you leave here."

And more than the point Charlie Munger makes about the importance of learning in our own progression, there is an obligation to learn that comes from a paraphrased idea attributed to Thomas Jefferson's:

"An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people."

So is learning important to help us grow as people? Most definitely. But is it also critical in maintaining any semblance of a free and informed democracy? Also yes. Without well-informed beliefs, we start to become reminiscent of Paul's description of children in Ephesians 4: "tossed to and fro, and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the sleight of men, and cunning craftiness, whereby they lie in wait to deceive."

As I sat with my own feelings of inadequacy when it comes to building formed opinions and belief, I landed on this idea: index your beliefs.

Index Your Beliefs

As I was unpacking what I meant by "index your beliefs," I was reflecting on the definition of the word "index" and I saw the word bibliography, and that felt perfect.

Take anything you feel strongly about, whether its technical, operational, political, religious, or anything else. Now, give me the bibliography of why you believe what you believe. That is your index.

I've referenced several times this quote from Charlie Munger about forming opinions:

"I feel that I'm not entitled to have an opinion unless I can state the arguments against my position better than the people who are in opposition."

Your ability to state the arguments for and against your position; that is the bibliography of your belief. The sources that have come together to construct your perspective. And if you haven't taken the time to audit why you believe what you believe, then, according to Charlie Munger, you may not be "entitled" to that perspective.

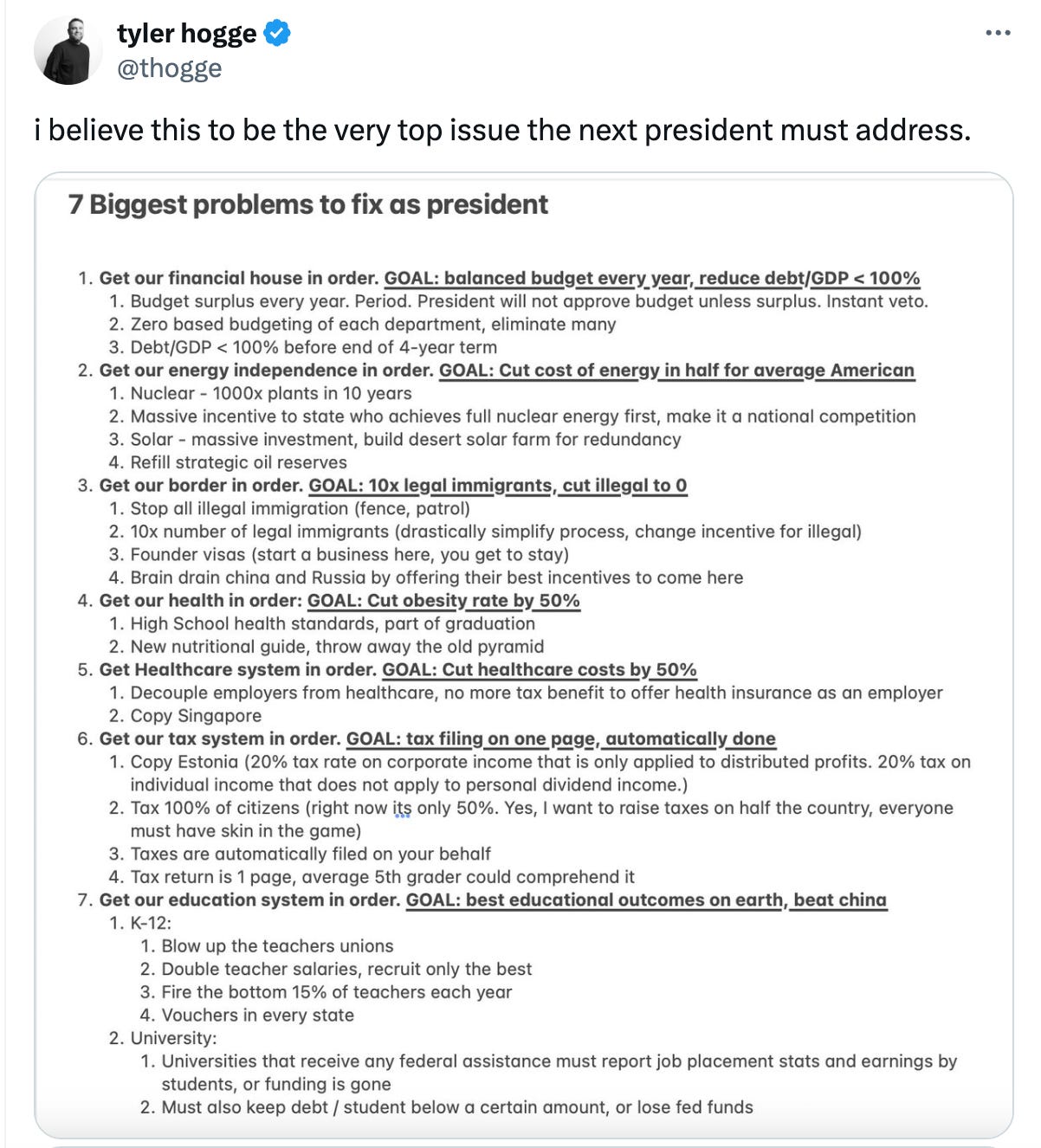

So as you form the index of your beliefs, what does that end up looking like? A big thank you to Tyler Hogge because it was one of his posts that made me frame the problem this way:

What Tyler did is, I think, the end result of indexing your ideas. Having them clearly articulated enough to rank them, and back them up with specific components.

But to go one step deeper in building a true index of your beliefs would require things like explaining why he thinks we should grow the number of nuclear power plants 1000x in the next 10 years. What is the information that has cemented that perspective for him?

Narrative Violations & Birthing Hype Cycles

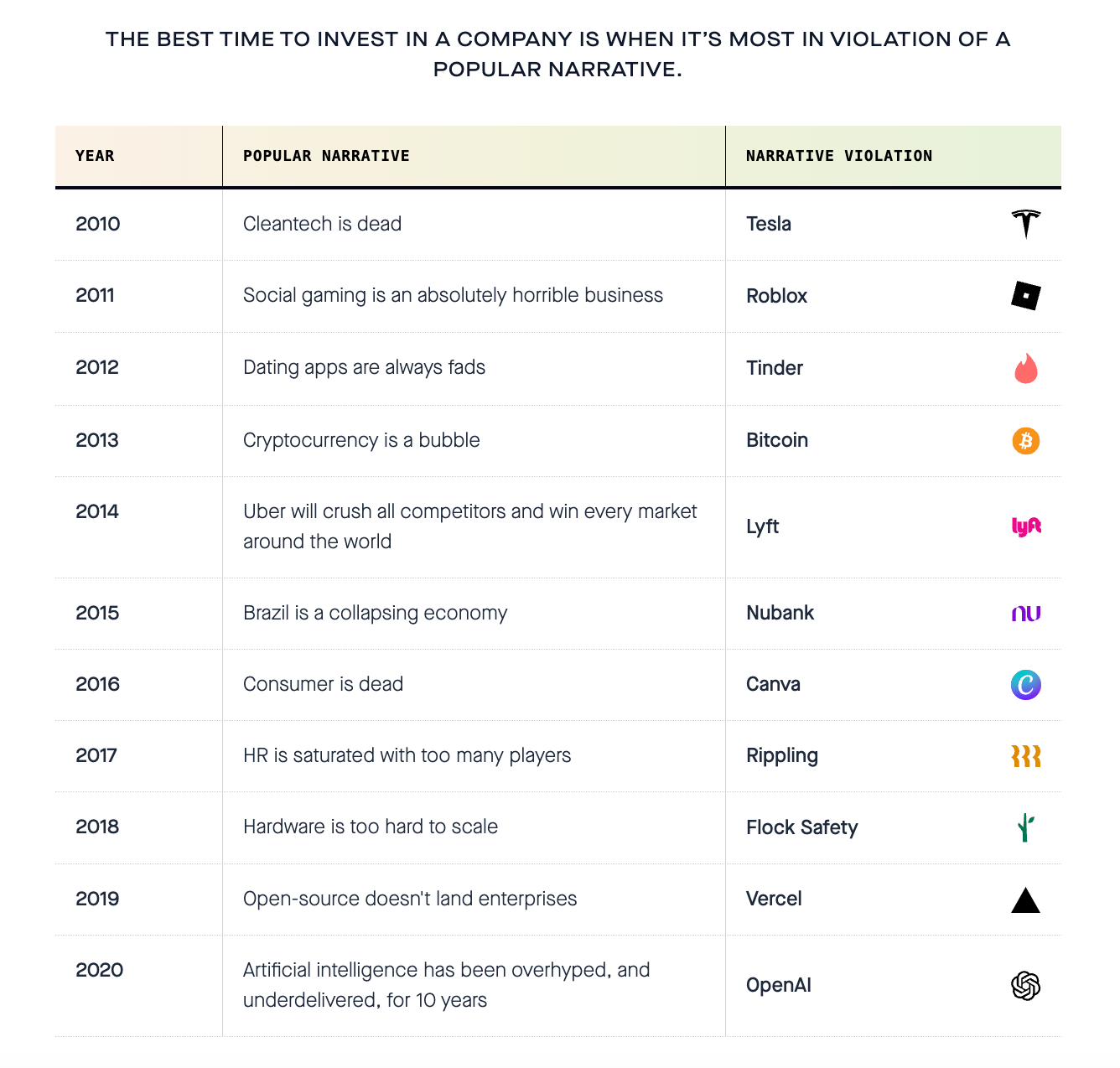

Before you set out to index your ideas, you'd be well served by revisiting an idea I've referenced before from Ralph Waldo Emerson: "never read a book that's less than a year old." In other words, there is a danger in any attempt at gathering information that you'll fall victim to the weight of popular narrative and recency bias.

One example of how to avoid falling in-line with the popular narrative comes from Bedrock, whose entire brand revolves around finding narrative violations.

A simple shorthand could be "do I think this company or solution is the best first-principles approach to something? Or do I think it is what most people think is the right approach to something?”

My very favorite framing of how to avoid popular narrative is to look for things that birth hype cycles, rather than ride them. Trae Stephens laid this out in a piece called "Venture Capital’s Space for Sheep." He explained better than I did how these hype cycles occur:

"The average investor does not spend all day simply searching for the best new company; they spend all day searching for the best new company in a socially approved technology “space.” Twenty years ago, that space was e-commerce, the “dot.com”-ing of brick-and-mortar stores. Fifteen years ago, “social-mobile-local.” Ten years ago, the “sharing economy.” Three years ago, gaming and crypto. Now, it’s artificial intelligence."

And most importantly, Trae makes it clear: "This herd behavior is not harmless." Read the full piece for his explanation of why, it’s great.

His piece lays out exactly how the best startups get built in ways that birth new hype cycles, rather than riding existing ones. And while he's specifically talking about how startups get built, I think the framing applies to most ideas:

A first-of-its-kind company can’t be categorized neatly in comparison to an existing company.

The founder is deeply passionate (even to the point of obsession) and knowledgeable about the sector their company is in.

The founder should have a “secret,” an understanding of a truth about the world that others have yet to recognize.

Not everyone would choose to invest.

The company has potential for a monopoly outcome.

With any idea you're exploring there is an element of ensuring that you're not following a broader group perspective into a hype cycle or popular narrative. Here's yet another Charlie Munger quote for you that I've also written about before: "Take one simple idea, and take it seriously."

The ideas that aren't what everyone else is thinking, that you can pursue with obsession to try and find an answer to, that you can exploit a secret you've uncovered, despite it not being popular with everyone, but that could end up being the most important idea or belief for you.

The Value of Ideological Exploration

There's so much more I think about this. But I've got a newborn, and a birthday party to take my eight year old to, and a plastic turtle my five year old just lost down the sink drain. So I'll leave the way I started; with a T.S. Eliot quote:

"We shall not cease from exploration. And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time.”

I want to index my beliefs and unpack a bibliography of the sources behind them so that I understand why I believe what I believe. Understanding what I believe will, truly, be arriving somewhere I’ve been before and knowing it “for the first time.”

And I think, despite the flood of information we're exposed to every day, we would be better suited if we took the time index our beliefs. Whether its the beliefs that determine how we live our lives, the religions we subscribe to, the investments we make, the companies we build, or the relationships we prioritize. Beliefs are made better through scrutinization.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Indexing feels like a really great method to slow down the overwhelm. I could almost visualize doing something like that on an excel sheet or notion. Loved the bit abt hype cycles especially! Great insights