The Regrets of a Tiger Mom

In 2015 my brother graduated from law school and the keynote speaker at his commencement was Amy Chua, a lawyer, Yale professor, and author of the book "Battle Hymn of The Tiger Mother." She was a captivating speaker and I came away impressed by the way she talked about grit and approaching life with determination.

I didn't think much about Amy Chua for the next 4 years other than knowing that her Tiger Mom book was on my list of things to read when I got the chance. In 2019 I finally read the book and was surprised by the contents. The book was much less Parenting 101 and more a long and uncomfortable story about what, to me, felt like verbal abuse and a tenuous relationship with her daughters at best.

She chronicled how she would berate, yell at, and ridicule her daughters into endless hours of practice on the violin and piano. I remember distinctly thinking to myself, "this doesn't seem okay. But then again, how many musical prodigy's have I raised? She must know what she's doing."

Soon after I finished the book I was googling Amy Chua and found out that in 2018 her husband (also a law professor) had been accused of sexual harassment. Any moral license I had been affording her for what felt like over-the-line parenting immediately went away. "No, there is a lot of weird stuff about her family. I don't think I'll listen to her."

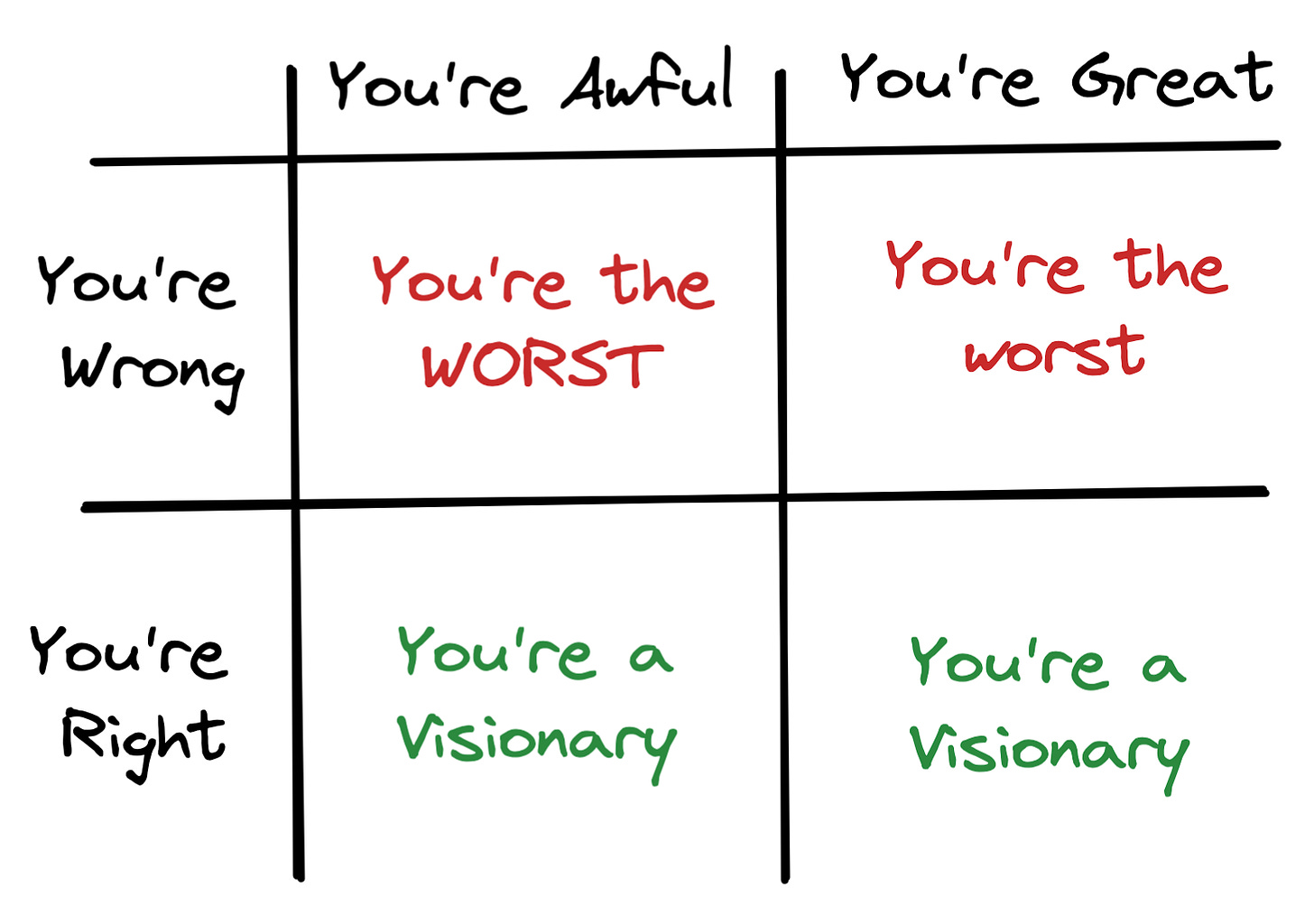

Now say what you will about tiger parents, law professors, and whether or not the bad behavior of a person's spouse should determine your perspective on them but the key point I often think about is this. The outcome, in this case, shaped my comfort with the means surrounding it. Whether we like it or not we're often not so much interested in the justification of the means so long as the outcome is something we can agree with.

In investing there is a question of whether something is a winner and, more importantly, whether you care very much about how it became a winner. I've always bristled at the idea in finance that any business has the fundamental purpose to "maximize shareholder wealth." That always struck me as a way to hide a multitude of sins. You can justify any number of behaviors as long as you "maximize shareholder wealth." Instead, it's critical to understand the good and the bad of the way you invest. Because whether you like it or not the ups and downs are part of the journey to get where you're going.

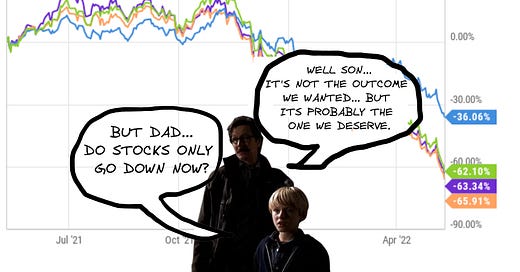

The Outcomes We Deserve

Very few people have been unaffected by the recent market downturn and looming recession. But think back to a long, long time ago in a different world, to mid-2021. Companies and investors alike were caught up in excess. Larger and larger rounds, bigger and bigger valuations, more and more dramatic amounts of burn. We're now looking back in retrospect and thinking "maybe X wasn't such a good idea after all."

A lot of people looked at one-click checkout as a massive opportunity. They laid out the thesis for how winning the race to control the customer checkout would be a great frontier opportunity in owning the relationship with the customer across merchant sites. After over $1B in funding you now have a defunct hype machine that never generated more than $600K in revenue and another getting sued by their largest customer.

In the crypto world we saw the recent implosion of the Terra Luna ecosystem. They launched with a big vision of getting people to use Bitcoin as a payments mechanism as opposed to credit cards. But when LUNA lost 99.9% of its value it led to $40B of value in the crypto market getting wiped out. When you consider the fact that Bitcoin can process ~4 transactions per second vs. 3K+ with Visa you start thinking, "maybe the world wasn't ready for this yet."

A lot of people are ready to jump up and down on these failures and even use the outcome as evidence of a bygone conclusion. But most of the time these are companies that got built around a lot of good ideas that just turned out to be wrong. And often investors are the fuel on the fire that is raging in the wrong direction.

"Private companies haven’t adjusted for today’s market—and venture capitalists are in part to blame for that. We collectively [told] companies to build [in] a very different culture than the culture we have today, economically. You read all of these blogs out there from investors saying, ‘Here’s what you need to do, companies,’ and the reality is, investors told companies to do a very different thing for the last two years. I think we collectively as investors need to acknowledge our huge role in this.” (Lydia Jett)

The insane prisoner's dilemma we've been in the for the last few years with investors and founders triggering each other's FOMO deserves a post all its own. But the key question that isn't getting asked enough among investors is "what role did I play in these companies that got ahead of their skis? What do I owe to those companies I've led astray? And how can I make sure that doesn't happen again?"

You'd Better Be Right

I've written before about two case studies of excess: Uber and WeWork. Uber is a $40B+ company generating $17B+ in revenue. WeWork is a ~$4B company with ~$2B of revenue. One company is seen as a success, one a failure. The failure wiped out ~$20B of capital invested. But the success had accusations of covering up sexual assault and harassment, property theft, and more.

The amount of cover an outcome can provide an investment is staggering. Bets on growth that don't work out are labeled ponzi schemes and huge financial successes are able to brush just about anything under the rug.

When you look at a company like Tesla, the reality is they've produced more cars than any company founded after 1967. Lots of people are still skeptical of the company, which is totally fair given Elon's unorthodox methods (to say the least). But those people will feel like they must be crazy because the outcome puts pressure on their healthy skepticism.

"I still, and I will sound like I'm absolutely crazy, but I still believe there is massive accounting fraud [at Tesla] and maybe it gets uncovered one day, maybe it doesn't." (Josh Wolfe)

The reality of capitalism may be that there isn't much you can do to change this. More investors, regulators, founders, and employees should try to hold companies accountable for the good and the bad that they produce. But if the outcome is making people money most of the time "the ends justify the means."

As an individual investor I can't change that that's how a large swath of the world works. But I can take that into account when I determine my own priorities and values. I can focus on my own circle of influence. I can work hard to make sure that my efforts are focused not just on the ends, but also understanding and feeling good about the means.

What Does This Mean For Venture Capital?

I love the writing Katherine Boyle has done on "American Dynamism." She's chosen to focus much of her investing efforts on companies "that support the national interest, including but not limited to aerospace, defense, public safety, education, housing, supply chain, industrials and manufacturing." She looks at venture as a vehicle that, for all its faults, is actually more effective in tackling these areas than a lot of government efforts.

"Venture capital is better at monitoring outcomes: it turns out that professional investors, even in a bull market, care more about value creation than bureaucrats who are not measured by or compensated for their success."

There is a "Good -> Better -> Best" framework in measuring outcomes in venture. “Business as usual” is focusing on investing in companies that seem to check the boxes and are on track to financial success. Having a focus on financial success vs. the alternative isn’t bad; it’s good. But there are better ways investors to align their efforts to the best outcomes.

The world needs more conviction-driven investors. Investors who aren't focused on what other people are doing or just on what can make money. Imagine the world you believe should exist, and then wonder whether the companies you're investing in will make that world more realistic or not.