This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Internet Friends

I have a few friends that are on my "just give me a call" list. We know that we can randomly call each other and if the other person is busy, they just won't pick up. It's fine. We'll catch each other next time. I was having a phone call with one such friend, and we were laughing hard. Like, "watching Hot Rod for the very first time as a 16-year old" brand of laughing.

Without thinking about it, I said, "Man, we gotta hang out more."

We chuckled. The chuckling slowed. We paused.

"We've never met in person, have we?"

You see, this was an internet friend. Someone I've met through the magic of Twitter, and probably wouldn't have met otherwise. As my friend and I talked about how weird it is to feel like such good friends, but to have never met, I started to think about it. And I realized ~75%+ of the people I interact with frequently (excluding people I work with), I've never met most of them in person.

Twitter Context

Twitter was a COVID discovery for me, I never really used it until the pandemic started. The combination of Roam and Twitter have dramatically improved my friend circle, my quality of thinking, and the volume of feedback I get on the stuff I'm working on.

This week, however, I had the unique experience of having thousands of people react to something I posted.

And two things happened: (1) I had a lot of people asking thoughtful questions about a company and outcome that was quite surprising, and (2) a lot of people questioning whether I was making the story up.

I wanted to address the second one first.

Now, my Mom tells me not to respond to criticism on the internet, and that I'm "special just the way I am." All good points. But one reason I wanted to spend some more time thinking about this is because I think I did a bad job of clearly communicating what I was trying to say.

Never at any point in my thread did I say, "look how right I was, aren't I a genius?" The model I built showed an aggressive growth path that, based on typical growth trajectories for a company, wasn't the most likely. The reason I thought it was such a fascinating story was because I happened to have landed at a $19.5B outcome 3.5 years before Figma got acquired for $20B. But in my model, I had that happening in 2025, and when they were at almost $1B of revenue. Not in 2022 when they're at $400M of revenue. So I was wrong.

But if you believe me when I say I know I was wrong, and the numbers matching up are just a coincidence, it should hopefully become easier to believe that the story is true. Also? Because I have the "receipts" to prove it.

Beyond me feeling obligated to defend my honor, there is a much more interesting discussion to have on this topic. I wanted to dig more into one of the ideas I talked about in the post, and some of the thoughtful questions people had like, "what did you see in Figma that made you believe in such a big outcome?"

Defying Gravity

I talked about this idea of financial gravity; basically that a company's ability to just continue to grow exponentially becomes increasingly difficult as they scale. And that you can look for the things that could make a company capable of defying gravity.

In Walter Isaacson's biography of Leonardo da Vinci, he has this great line about the rules of art:

"The Last Supper is a mix of scientific perspective and theatrical license, of intellect and fantasy, worthy of Leonardo. His study of perspective science had not made him rigid or academic as a painter. Instead, it was complemented by the cleverness and ingenuity he had picked up as a stage impresario. Once he knew the rules, he became a master at fudging and distorting them."

In investing there are some rules of thumb, some expectations, and guidelines. One such rule-of-thumb is the idea that a good company will see revenue growth where they triple-triple-double-double-double in revenue.

Other guidelines are thinking about what revenue or earnings multiples companies will trade at. This way of comparing different companies has become even more relevant during a market correction where private companies have 2-3x the valuation of public comps that have 4x more revenue.

Different idealogical templates for how to think about a business, how it will scale, the things they need to do, and the likely outcomes / upside all help form heuristics for what we can expect. These are like Da Vinci's rules of art. But instead of becoming academic, and believing those generalized rules are the only reality? We can instead look for the reality of the unrealistic outliers.

Figma: a Case Study

Before I dive into some thoughts that I had on Figma, I wanted to reiterate an important reality from my Twitter thread. I'm not trying to say I'm a genius, or that I called it. There's a lot I got wrong. And every company is different, and exists in a vacuum where they'll have a million different unforeseeable forces impacting their outcomes.

But there's a reason I felt comfortable enough to walk into an interview and try and defend a $20B outcome for a company that had ~$4M of revenue. And there is value in paying attention to some of the common characteristics that allow a company to "defy gravity." So I tried to lay out some of the characteristics I’ve seen.

Building "Delightful" Products

Every time I mention this concept it feels fluffy, and indefensible. "Oh, just build a good product? Yeah, no duh." But this feels like the bedrock foundation that almost every good company is built on, at least for companies started within the last 15 years.

Certainly, companies like Oracle or Microsoft have built products that aren't exactly delightful. Their approach has been more like a bad relative who moved in with you for a week to get "back on their feet," and now they're so deeply entrenched in your finances, and social circles, and TV-worthy comedy-dramas that you'll never get rid of them.

But even older companies, like Apple? Delightful products that people are obsessed with. That product love just does not go away. I always find myself coming back to this quote from Eric Glyman, the CEO of Ramp:

“As always, our top priority is empowering our customers with incredible products and building the team and culture to deliver on that. These inputs — customer focus, product obsession, and commitment to talent — are what we focus on every day. Growth is just the output.”

People love Ramp, not because it's the only corporate card, because it’s not. But because it's a ridiculously good product. And that product obsession keeps people coming back for more. It doesn't mean they'll never have any problems, but it increases the likelihood of outsized success.

You can build a company with products that aren't delightful. But the weight of gravity will always press down on you because your customers don't love your products. Figma's customers love their product.

Solving Problems That Exist

Another "no duh," but one that I can't stop thinking is fundamental. One, maybe surprising, example I saw recently in a thread about creator economy startups. A lot of these companies are struggling right now. The thread articulates really well why that might be the case, so I won't go into that. But the one creator economy startup that isn't struggling to monetize is OnlyFans.

Say what you will about their business, but the problem-centric reality is that many creator economy startups are solving problems that don’t exist, or doing it for an audience that can’t pay for it. OnlyFans identified customers that have actual problems for their specific audience (security, social verification, etc.) And it's an audience that is willing to pay for those solutions.

That's the two-fold aspect of solutions that solve actual problems. If the problems are meaningful? Then people will pay for them. Identifying a problem that is not only real, but palpable—that's the trick.

"What would someone pay to alleviate the problem they're having?"

You can build a company solving problems that don't really exist. But the weight of gravity will always press down on you because your customers don't love your products. Figma solve a problem that existed.

Addressing an Unaddressable Market

Market sizes can be fickle things, especially when they don't seem to be very big. It can be hard to address a market that no one can really see. For Contrary Research, we've written dozens of reports about different companies and we always start with the same section: the "thesis."

The way I describe a thesis is (1) what is the powerful tailwind that exists independent of this company? And (2) how is this company well-positioned to take advantage of that trend? The better you understand that first tailwind, the better you can assess the market.

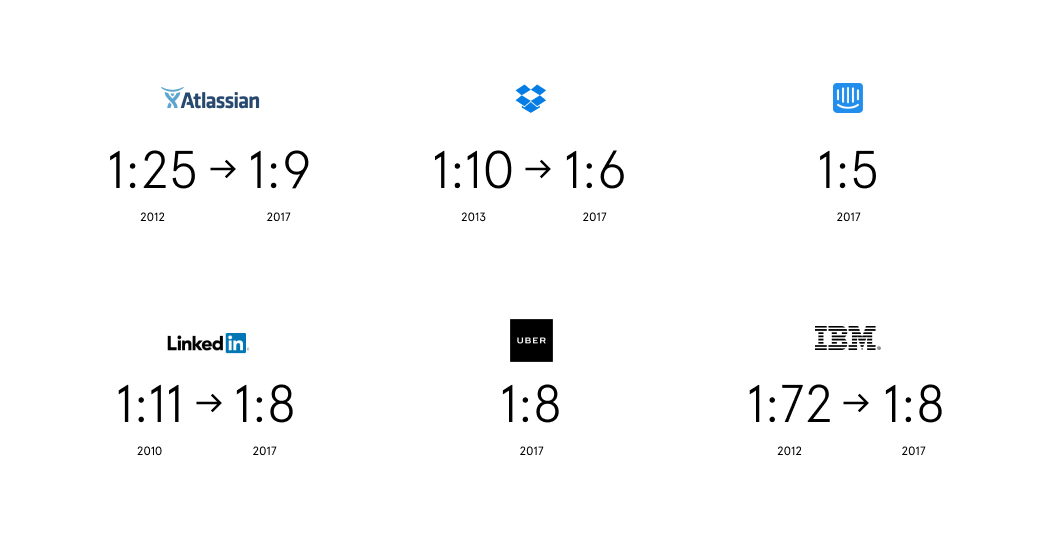

From the early days of Figma, the CEO Dylan Field, was already tapped into this idea of the increasing importance of design. He has a famous graphic that he wrote about in 2017 where he shows how the ratio of designers to engineers was starting to shift. You see companies like IBM go from 1 designer for every 72 engineers down to 1 designer for every 8 engineers.

That genuine market wave is often illusive because it’s hard to see it coming until it smacks you in the face.

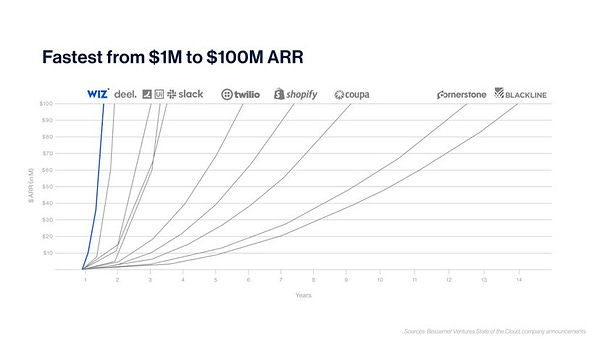

Another example is cloud security. The prevalence of the cloud has been rapidly increasing for years; AWS was founded in 2006! But cloud security only recently popped into the zeitgeist with companies like Wiz (founded 2020) and Lacework (founded 2015). The trick is spotting those markets that can enable a company to defy gravity.

You can build a company with a so-so market. But the weight of gravity will always press down on you because you have to scrap and fight for every single customer and dollar, because no one is looking for you. Figma tackled a market that was large, but more importantly? Growing.

Other Examples?

These are the kinds of examples that people should constantly be looking for, and studying: businesses that can defy gravity. Study the commonalities in how these companies’ unique positions set them up to defy any of these standards and rules-of-thumb.

When you look at some of the best acquisitions of all-time you see companies like Instagram or YouTube that have scaled at ridiculous rates.

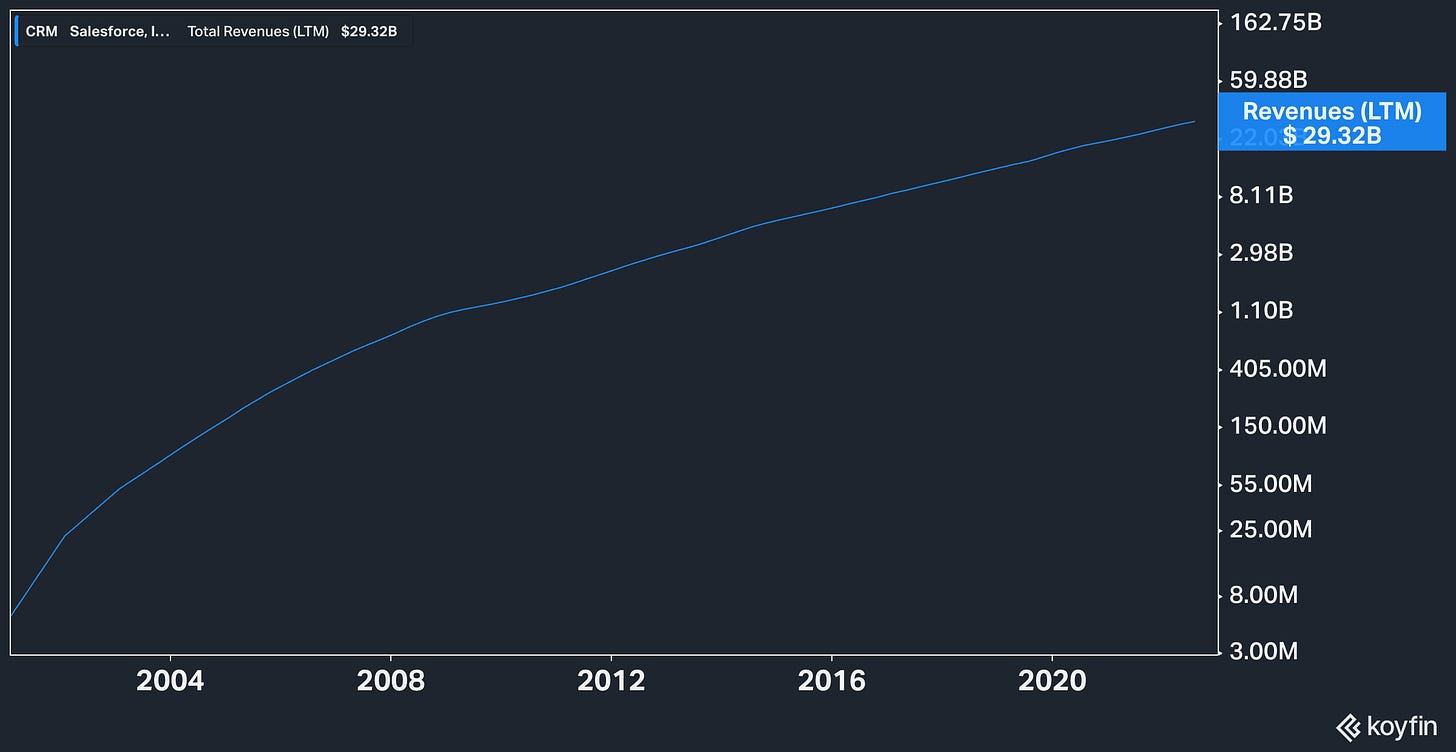

Or you have companies like Salesforce. From the time they went public in 2004 they had 14 quarters of 50%+ growth, and aside from a few quarters, they have grown at least 20% every quarter for almost 20 years straight!

What is Conviction?

At the end of the day a lot of these things can feel like platitudes. I've listed a few here that I have seen consistently across gravity-defying companies. They almost always have incredible products solving meaningful problems in a market that is unstoppable. But there are others. My key takeaway from looking back on Figma as an example wasn't to say, "here are the reasons I nailed it." It's to appreciate that the very best companies have exceptional characteristics that you have to look for.

And no, I don't believe that these kinds of exceptional outcomes are the simple result of massive waves of free money from the Fed, or whatever hand-wavey macro justification you want to try and slap on it. Every business is operating in the same economic environment. And yet, some still become exceptional.

But these gravity-defying characteristics aren’t the whole equation. It’s one thing to identify some characteristics that make a company special. But nothing matters if you don’t do anything about it. At the end of the day, I can ask myself “what do you have to believe about this company?” And make my pros and cons. But real conviction is becoming a part of the story. Investing in the company. Or better yet? Going to work there. No better way to go all in on something you have actual conviction in that to put your life and career behind it.

When I had that job interview I was focused on a different style of investing; more slow and stable. It’s one of the reasons that interviewer was so skeptical of my expectations. And that was a turning point for me, where I decided, “If I’m going to be investing in companies, I want to be investing in the companies that at least have the potential to defy gravity.” It’s one of the reasons I went on to work at firms like Coatue, and Index instead (both investors in Figma 😉).

That desire to invest in gravity-defying companies is also the reason I’m so excited about Contrary. The ability to back exceptional people, even before they start companies, gives me a front-row seat to some of the most exceptional builders, and I wouldn’t trade that for anything.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week: