This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In 11th grade, I got punched in the face. I remember vividly walking through the crowded halls of my high school. I saw a kid approaching me who I knew and had even sat next to in my physics class. He was almost skipping towards me. Before I knew it, I was simultaneously hearing him say, "I don't like you motherf*cker" and seeing his fist connect with the side of my face.

I didn't fight back. I don't even remember being mad. I also didn't get too hurt. After a check for a concussion, I was fine. See, I didn't grow up in a violent home or on a violent block. I didn't really get in fights. That was the first and only time I've been punched in the face. But despite my limited experience with violence, it is an ever-present backdrop of life that most of us try and put at the back of our minds.

From school shootings to home invasions to police brutality to testosterone-fueled brawls to CEO assassinations, violence is everywhere. And often we try and wrap all these different faces of violence into one narrative. Human psychology leads to particular outcomes for particular reasons. But the reality is that one key medium of violence is both fundamentally different than most others, and its dramatically more impactful than anything else. That medium of violence is geopolitical conflict.

I think about this similarly to how I feel about recycling. Worrying about smaller individual elements of violence misses the mark the same way that focusing on recycling misses the point. If the massive oil and agriculture businesses don't manage their emissions, our recycling doesn't matter at all. If global conflict isn't managed effectively, no smaller incidents of violence are going to matter as much.

As I am so wont to do, I've turned to movies to unpack my perspective on how to think about military might, conflict, and deterrence. And I'm in good company with people like Palmer Luckey using movies like Avatar to unpack similar concepts. In a wave of defense tech investments and American Dynamism, it's more important than ever that people shape their perspectives on what they are or aren't okay with believing.

Vision's Conflict Equation

I started thinking about unpacking my thoughts here after watching The Incredibles 2 with my daughter (more on that later). But where I landed for my first anchor point was remembering a line from Captain America: Civil War. The governments of the world have proposed mandating oversight of the Avengers in light of some missions gone awry. The line comes from Vision:

"I have an equation. In the eight years since Mr. Stark announced himself as Iron Man the number of known enhanced persons has grown exponentially. And during the same period the number of potentially world-ending events has risen at a commensurate rate. I'm saying there may be a causality. Our very strength invites challenge. Challenge incites conflict. And conflict breeds catastrophe."

A very similar argument has been applied to the United States. From interventionist policies to conflicts between growing great powers, the US most certainly projects strength that has invited challenge.

And with the Avengers, Vision's point is an accurate one. Plenty of the conflicts these superheroes have found themselves in have been the result of the rise of villains that their actions ended up causing:

Obadiah Stane (Iron Man): While Obadiah was already a corrupt arms dealer, Tony Stark's creation of the Iron Man suit led to Obadiah’s creation of a similar weapon, the Iron Monger Armor, that, but by the skin of Tony’s teeth, could have been sold to every terrorist organization in the world. Tony Stark's invention of Iron Man led to Obadiah's Iron Monger Armor.

Ivan Vanko / Whiplash (Iron Man 2): Ivan's father, Anton, was the co-inventor of the arc reactor with Tony Stark's father, Howard, but was later deported by Howard when Anton tried to sell the technology. Tony's use of the arc reactor technology led to Whiplash's rise.

Adrian Toomes / Vulture (Spiderman: Homecoming): Originally running a salvage company, Adrian is put out of work by the Department of Damage Control (DODC), a partnership between the Avengers and the U.S. government. The Avenger's involvement in the cleanup radicalized Adrian to becoming an arms dealer.

Ultron (Avengers 2): Tony Stark and Bruce Banner create an AI program called Ultron that comes to the conclusion that peace can only come through eradicating humanity. The Avenger’s use of one of the infinity stones led to Ultron as a threat.

Killmonger (Black Panther): The father of T'Challa, the King of Wakanda, was T'Chaka. In the early 90s, T'Chaka found out that his brother, N'Jobu, had been assisting black market arms dealers in stealing Vibranium and attempting to arm militant groups around the world. When N'Jobu threatens another Wakandan, T'Chaka kills his brother and leaves N'Jobu's young son to grow up with intense resentment towards Wakanda. The Black Panther's tactics led to Killmonger as a threat.

Situations like this lend credence to the idea that power invites challenge. If it wasn't for the Avengers in these situations, the conflicts may never have arisen. The same is true of America's power and interventionist policies over the last 50 years.

Vietnam (duh).

The coup that the CIA orchestrated to overthrow Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953, which led to the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

The 2003 invasion of Iraq under false pretenses that ultimately led to the rise of insurgent groups, including the Islamic State.

The 2011 toppling of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, which left the country in a state of ongoing conflict and instability.

There is an entire discussion to be had around attempts by the US to shape the world to their will and the consequences that has wrought. Much of the US's interventionist efforts in the Middle East are, face-palmingly, the result of power looking for problems. In 1991, Colin Powell quipped about the lack of formidable opponents on the world stage: "I'm running out of demons. I'm running out of villains.”

Lots of people at every key turning point throughout history have tried to make a similar argument that we're experiencing an "end of history." That massive conflict is no longer viable.

Palmer Luckey often tells the story of a book written in the early 20th century called The Great Illusion. In that book, an English economist and politician named Norman Angel laid out why war in Europe had become impossible and that spending money on building militaries that could deter conflicts was a waste since those resources would be better spent on building a utopia. The book was the number one bestseller in 1909. Five years later, World War I started.

That same idea has been perpetuated in each generation; the idea of the “end of history.” There are no more great wars. No more great power conflicts. But the reality is the opposite. And just like World War I shattered the overconfident triumphalism of Europeans as expressed in books like The Great Illusion, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has destroyed the complacent post-Cold War belief that great power conflict was a thing of the past. Trae Stephens put it this way:

“People are starting to realize that the geopolitical end of history did not actually occur, and there are still bad people that want to do bad things to innocent people in the world. And someone has to stand up for them, otherwise they’re just going to get walked over. I think it's less popular to think that we've reached an end of history than it was just even a few years ago.”

History has proven time and again that there are always people who believe they can accomplish their goals through violence. And though there are certainly unforced errors in the conflicts the Avengers have created for themselves, there are also conflicts that are caused by threats that would have existed with or without the Avenger's presence of power.

Danger With Or Without Response

In Captain America: First Avenger, the primary opponent is Red Skull, the leader of the Nazi science division, Hydra. Even if Captain America had never been created, Red Skull would still have found the Tesseract and would have still been on the war path to nuke major American cities. Captain America's strength didn't deter Red Skull, but it did defeat him.

Thanos was hunting for the Infinity Stones long before the Avengers had anything to say about it. Far from inviting the conflict, the Avenger's power actually was inadequate to prevent Thanos' successful genocide of half of all living things throughout the universe the first time. It was only the Avenger's collective strength that was ultimately able to defeat Thanos and save trillions of lives.

In our own world, there are threats that, whether the US was around or not, would still exist. While you can make arguments that relations with Russia or China have exacerbated certain conflicts, they have certainly not created them. Both Russia and China have demonstrated massive ambitions to rebuild the empires they believe to be their birthrights. China's century of humiliation. Russia's longing for a return to the Soviet Union, whose breakup they consider the "geopolitical disaster of the century."

Some might point to the idea of cultural equivalence. Russia, China, the United States. They have positives and negatives, each vying for strength here or influence there. But recognizing what is at stake isn't always as easy as it is in the movies. The guy with the scary red skull face who is also a literal nazi? Definitely the bad guy. The giant purple monster with the nutsack chin who wants to wipe out trillions? No brainer the villain. But make no mistake, there are villains today. The idea of cultural equivalence is misleading. Palmer Luckey, the founder of Anduril, doesn’t mince words when it comes to the stark contrast between the value system of the US and its peer competitors:

“No matter what your reservations about the US military are, and they’re not perfect, but they’re definitely better than Russia or China. You need people to understand that this idea of cultural equivalence is a lie. There’s this popular idea in certain groups of people that all cultures are different, but fundamentally equal in some way. ‘Our culture [isn’t] better than theirs, it's just different.’ And I totally disagree. There are cultures around the world where it is a legal norm, and a cultural norm, to execute homosexuals, not give women equal rights, lock up people of a certain religion in reeducation camps, kill journalists… These are things that are not just legally accepted, they’re culturally accepted. In the United States, our culture does not tolerate that. We believe in strong Western values of a liberal democracy, strong checks and balances, freedom for everybody. And there are, of course, pockets of problems here and there, but fundamentally, I think the US is nearly ideal as a culture.”

So first, we have to recognize that not all conflicts are unforced errors of our own doing. There are also threats from opponents that represent existential risk and span a dramatic difference of values. In response to those threats some people feel content to address these conflicts not through power or deterrence, but through infrastructure. Diplomacy, economic sanctions, and summits. That's the kind of response we see in the world of The Incredibles.

Incredibles vs. Infrastructure

The world of The Incredibles shows us a massive pool of liability against superheroes. A suicide attempt is foiled by Mr. Incredible and the wannabe dead guy sues. That unleashes a wave of litigation that sends superheroes into hiding. In particular, The Incredibles 2 shows us the infrastructure that society has built to deal with the conflicts that superheroes would have handled previously.

At the beginning of the film, The Underminer emerges, makes his villainous speech, and tunnels under a number of banks, breaking into their vaults and robbing them. While The Incredibles attempt to stop The Underminer, they're unsuccessful and end up arrested. In interrogation, they have this conversation:

Mr. Incredible: We didn't start this fight.

Cop 1: Well you didn't finish it either.

Cop 2: Did you stop the Underminer from inflicting more damage?

Mr. Incredible: (begrudgingly) No.

Cop 2: Did you stop him from robbing the banks?

Mr. Incredible: (defeatedly) No.

Cop 2: Did you catch him?

Mr. Incredible (frustrated) No!

Cop 1: The banks were insured. We have infrastructure in place to deal with these matters. If you had simply done nothing everything would now be proceeding in an orderly fashion.

And that's true. When I reflect on that particular conflict, infrastructure could have done the job. The Underminer would have come, robbed, and left. In a world of weird mole-esque villains, thats a risk that can be underwritten by banks.

The same is true of the core villain of Incredibles 2. Screenslaver, also known as Evelyn Deavor, rises in response to hating superheroes because their unavailability led to the death of her father. I would put that in a similar bucket as Ultron or Killmonger; an unforced error.

But when I reflect on other conflicts The Incredibles have faced, like Syndrome's robot, it's less clear. Granted, Syndrome wouldn't exist if he wasn't a spurned super fan of Mr. Incredible. So this one teeters on the edge of unforced error. But taking the robot specifically, Syndrome wanted to play hero, sell his inventions, and retire. But the robot was too smart, disarmed Syndrome's control, and was going to wreak havoc on the city unless it was stopped.

See, infrastructure can be used to address conflicts that are understandable and / or quantifiable. And while those conflicts exist, like The Underminer, or The Korean War, there are certainly exceptions. This brings us to Joker-style conflicts.

Watch The World Burn

The Dark Knight is another exceptional example of unpacking particular conflict psychology. In Batman's conflict with the Gotham Mob, they turn to the Joker. Bruce Wayne's analysis of the situation elicits this exceptional conversation with Alfred:

In response to Bruce Wayne's opinion that the mob has "crossed a line," Alfred responds, saying:

"You crossed the line first, sir. You squeezed them, hammered them to the point of desperation. And in their desperation they turned to a man they didn't fully understand."

Bruce Wayne is dismissive of this idea, saying "criminals aren't complicated. We just need to figure out what he's after." Alfred's response goes down in history as one of the greatest monologues of any movie, let alone any superhero movie:

"With respect Master Wayne, perhaps this is a man you don't fully understand either. A long time ago I was in Burma and my friends and I were working for the local government. They were trying to buy the loyalty of tribal leaders by bribing them with precious stones. But their caravans were being raided in a forest north of Yangon by a bandit. So we went looking for the stones. But in six months we never met anyone who traded with him. One day, I saw a child playing with a ruby the size of a tangerine. The bandit had been throwing them away. So why steal them? Because he thought it was good sport. Because some men aren't looking for anything logical like money. They can't be bought, bullied, reasoned, or negotiated with. Some men just want to watch the world burn."

Some conflicts, some opponents either cannot be understood or cannot be quantified. Take 9/11 for example. At the time, security protocols assumed that hijackers would typically use the aircraft and its passengers as bargaining chips to negotiate political demands and that the general strategy for dealing with hijackings should involve compliance, aiming to ensure the safety of passengers by negotiating or following hijackers' demands.

Kamikaze tactics, in general, are difficult for most modern military tactics to address because in most conflicts there is an element of each sides strategy that involves self-preservation and even maintaining the possibility of retreat. When the enemy is not only willing but eager to die, those can be conflicts that are hard to understand.

But the second bucket of conflicts are those that are hard to quantify. And more, even, than conflicts that are hard to understand, these unquantifiable risks are the biggest ones that are facing us right now.

Unquantifiable Conflicts

Right now, the conflicts staring the world in the face are difficult to quantify. And these are not desert skirmishes caused by unforced errors and American overreach. These are the makings of World War 3.

From Russia's invasion of Ukraine, to Iran's support of Palestine as a proxy for Russia against America's alliance with Israel, the protests in Georgia against a pro-Russian ruling class, martial law declarations in South Korea over North Korean threats, and Chinese threats in the South Chinese Sea over Taiwan.

This is not business as usual.

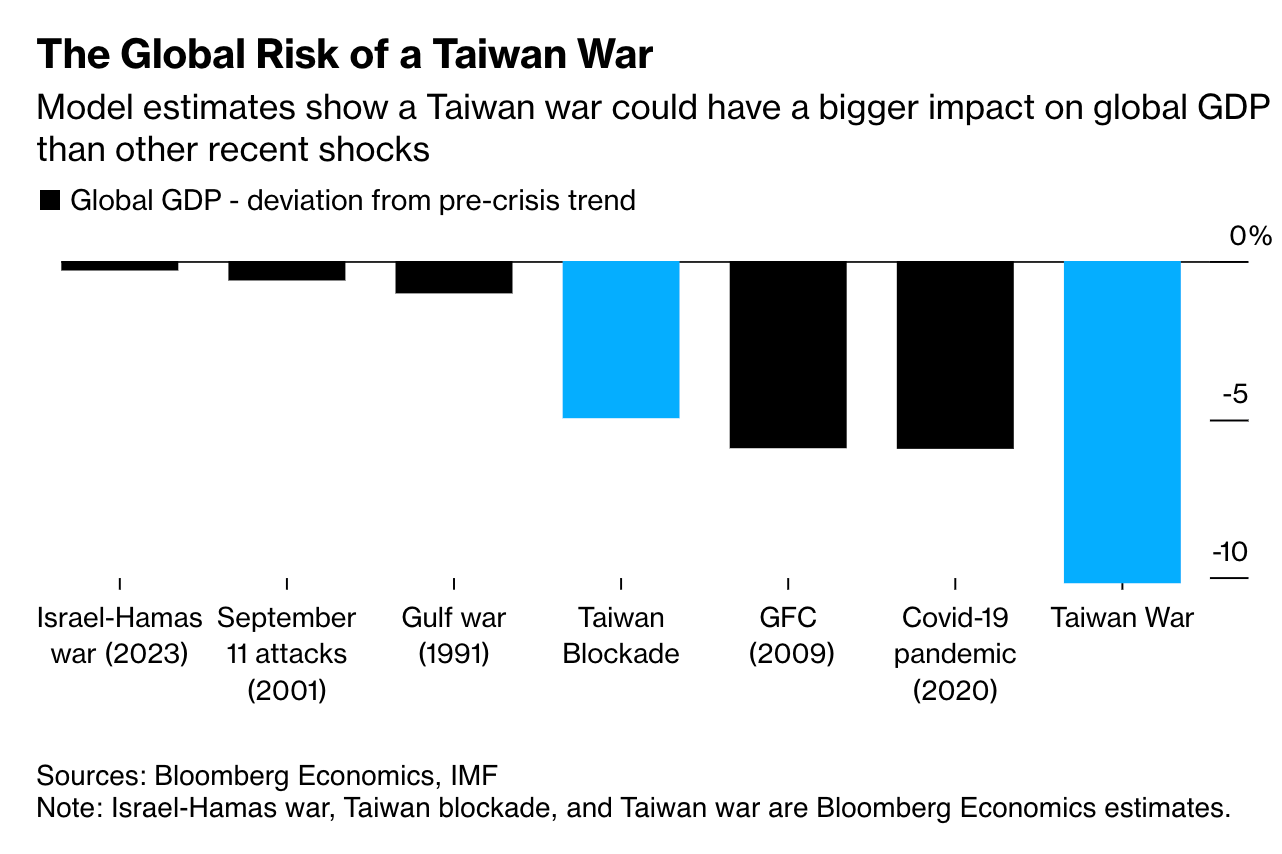

Take Taiwan as just one example. Given the central failure point of the entire semiconductor industry in Taiwan, the economic implications are almost literally unquantifiable. One estimate put the cost of a war over Taiwan at $10 trillion, dwarfing previous economic crashes like the financial crisis or Covid.

As a result, it's clear that "infrastructure" isn't going to cut it in the current conflict environment that we're facing. Economic sanctions against Russia are pushing them into the arms of the Chinese. Tariffs against Chinese imports or restrictions on things like chips into China are raising tensions. And while some still think we're in the "infrastructure can deal with these matters" territory, I don't think we are. On a panel in January 2024, retired Major General Cameron Holt said “there’s a lot of talk in the press about China. There’s a lot of good speeches about it, [but] frankly, I still don’t believe we’re on a wartime footing.”

That’s not casual talk. The risk is real and not within the standard underwriting parameters that our established infrastructure can deal with. We need something different. We need a hero.

Holding Out For A Hero

Reflecting on what superheroes like Iron Man, Vision, Mr. Incredible, and Batman have taught me, it leads me to the conclusion that we need a hero. And, unfortunately, calling the American military as an institution a hero could be considered a controversial take at best.

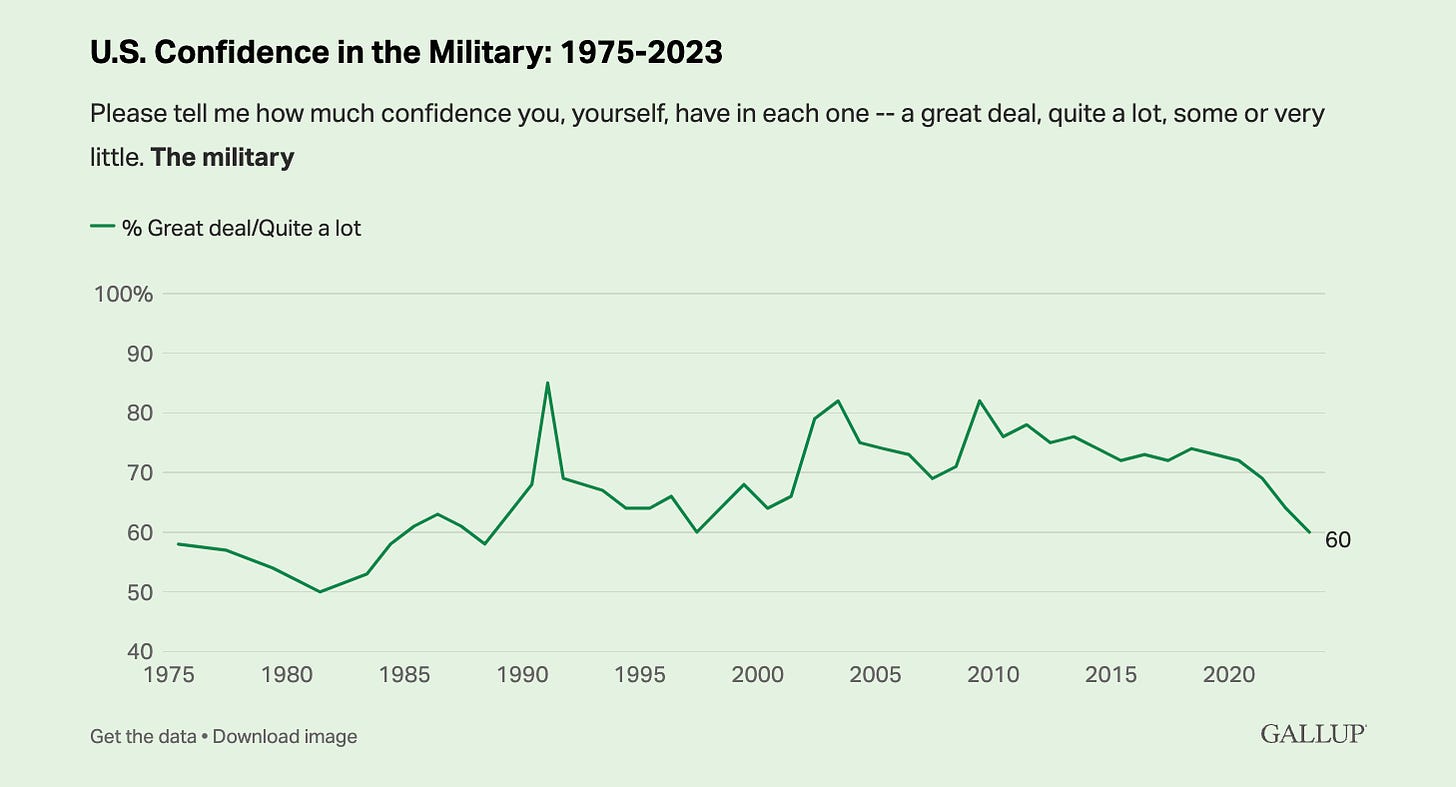

Don't get me wrong, when it comes to veterans, Americans have pretty consistently held the belief that, not only are they heroes, but they deserve more than they get. But the US military, as an amorphous institution, trust in that institution hasn't been as low as it is now since 1988.

But the reality goes back to the point that Palmer Luckey made earlier:

“No matter what your reservations about the US military are, and they’re not perfect, but they’re definitely better than Russia or China. In the United States, our culture does not tolerate [injustices like murder or imprisonment of journalists or specific religious groups]. We believe in strong Western values of a liberal democracy, strong checks and balances, freedom for everybody."

We may have unforced errors that, per Vision's equation, we've invited on ourselves through interventionist policies and international bullying. We may have quantifiably understood conflicts that infrastructure like diplomacy and sanctions can manage. But we're re-entering a world we haven't really known since the end of the Cold War.

John Mearsheimer's book "The Tragedy of Great Power Politics" explains the reality of our anarchic international system and how that compels great powers to seek dominance. His seeming conclusion is that this cycle is doomed to repeat itself unless the international paradigm changes. Barring the introduction of a Starfleet-like superpower of peace, we're in that cycle whether we like it or not.

So instead of decrying the reality of great power conflicts, we have to ask ourselves—who would we prefer to have power? And, increasingly, there is a visceral hatred and dismissal of the United States government. There have been pockets of that forever, particularly during Vietnam, Watergate, the Iraq War, etc. But in my perspective, that hatred of the US government is a privilege. It reminds me of the quote:

"I disagree with what you have to say, sir, but I will defend, to the death, your right to say it."

The very fact that you can hate America while being in America, taking advantage of the benefits of America is, in and of itself, a benefit of America. You don't have the same luxury in Russia or China.

So, despite the weaknesses of the heroes we have, we have to ask if we believe they are the heroes we need? Because if we don't, if we cast them off, if we demure in our responsibility to stand against authoritarians like Russia and China, then we may find that we didn't deserve the heroes we had. And the result will be a very different outcome.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week: