What's In a Brand?

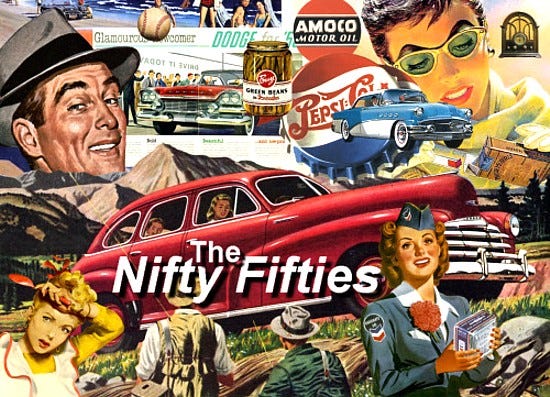

In the 1950s when brands had their Don Draper-drenched hey day people used brand recognition as a short-hand to recognize quality and trust. We drove our Ford Mustang to McDonalds for a Coca-Cola.

Fast forward through Vietnam, Watergate, Chernobyl, the Gulf War, and #FreeBritney we're all feeling pretty bummed out. Less than 35% of people have confidence in institutions and the default trust we gave to brands has been diminished.

More than ever we're interested in following people that we can empathize with and idolize. The most followed accounts on Instagram are people like Cristiano Renaldo, Kylie Jenner, and The Rock. Some of the most recognizable people in the world are right up there with the most recognizable brands like Nike and Coca-Cola in their influence.

David Perell Nailed It

The "Writing Guy" on Twitter, David Perell, wrote a fantastic series of posts on what he calls "Naked Brands." He walks through examples across basketball, fashion, and music but the core idea is this:

"Inspired by transparency, [popular influencers] have built loyal followings, and now, they are building companies. Successful influencers are perceived as genuine, sincere, and most of all, transparent. They differ widely from institutions built during the industrial era. Brands built during the late-industrial era garnered trust through mass marketing, as opposed to transparency. This is no longer a sustainable strategy."

The example that stuck with me the most was his description of the difference between the NFL and the NBA. In the NFL the focus is largely on teams and individual celebrity is more rare. But the NBA "encourages each athlete to showcase their individuality. The league encourages its athletes to assume vocal roles in politics, culture, and social action. It operates with an ethos of sincerity."

The increased emphasis that people are putting on individuals creates an unbundling of power in these industries. "Individual personalities replace gatekeepers as the drivers of style and culture." Where you traditionally had brands in fashion, studios in movies, and labels in music dictating what would rise to the top you're seeing a massive breakdown in the power of gatekeepers and an emphasis on the individuals with whom people empathize most.

The most poignant example of a gatekeeper mentality comes in the form of a quote from 2005 that my friend Rex Woodbury wrote about in his post, "Down with the Gatekeepers"

"There is not that much talent in the world. There are very few people in very few closets in very few rooms that are really talented and can’t get out. People with talent and expertise at making entertainment products are not going to be displaced by 1,800 people coming up with their videos that they think are going to have an appeal." (Barry Diller)

The year Barry Diller said this was the same year YouTube was created and proved that there were a lot more talented people in the world than anyone realized. Granted, in 2022 the vast majority of expressive and economic creation is still going through gatekeepers. But the world has woken up to the weaknesses of that model.

"I am emphasizing the self-service nature of these platforms (AWS, Fulfillment by Amazon, and Kindle Direct Publishing) because it’s important for a reason I think is somewhat non-obvious: even well-meaning gatekeepers slow innovation. When a platform is self-service, even the improbable ideas can get tried, because there’s no expert gatekeeper ready to say “that will never work!” And guess what—many of those improbable ideas do work, and society is the beneficiary of that diversity." (Jeff Bezos)

What Does This Have to Do With Venture?

When you look at the OG venture capital model it feels most like the monolithic brands. When the VC industry first got started in the 50's and 60's it was 20 people, all connected to Arthur Rock, a lot of whom were related. Fascinating enough, since then the names that started the show are a lot of the same ones who are best known today: Sutter Hill (1964), Mayfield (1963), Kleiner (1972), Sequoia (1972), and NEA (1978).

We've seen some meaningful new entrants, like a16z (2009) and Tiger's private market splash in 2021 (though they've been around since 2001). But by and large venture has stayed the same since its earliest days. Big monolithic brands used by founders as a short-hand for quality whose decisions are controlled by an investment committee behind closed doors.

When I first started as a VC the energy was very different than it is today. Investors have typically thought of themselves as gatekeepers (though probably not out loud.) Founders need capital for their businesses to survive and investors have the capital. It was a buyer's market to the benefit of VCs everywhere.

A lot has changed in the last few years, but two big things have shifted startup financing into a seller's market.

Starting a Company Got Cheaper

In the old days starting a company had a massive capital outlay. Founders had to rack their own servers and build everything from scratch. Even in 2012 Mark Suster had made the observation that the cost of starting a company had dropped dramatically.

The less capital required to start a company means there will be more companies. More shots on goal. And the number of winners didn't stay the same. There are more large-scale successes which means VCs have more and more companies to compete for.

The Amount of Capital Available Got Bigger

The amount of investable capital has also risen pretty dramatically with VC dry powder growing from $75B in 2018 to a record $222B in 2021. Some people think of this as a temporary stop-off for tourist mega funds from the public markets. I'm sure that could be some of it. But I think there is something bigger at play.

We're seeing the professionalization of startup investing as an asset class. The risk of starting a company has gone down and big money has caught onto the absolutely mind-blowing potential returns that some funds have seen and they want a piece of the pie. My guess is the amount of capital investing in startups will never normalize to previous lows.

Breaking Down The Gates

A lot of investors wish they could back to the way things were (again, probably not out loud.) A time when founders would flock to them, pay the gate tax, and thank them profusely.

One of the simplest examples of the diminishing power of VC's gatekeeping abilities? 50 years ago Sequoia set up shop at 2800 Sand Hill Road. One of their core principles? “If we can’t ride a bicycle to [the company], we won’t invest.”

Now? No one will go to Sand Hill Road. I started at a venture fund in Palo Alto and even 6 years ago it was tough to find times founders were making the trek to the South Bay. You have a generation of younger founders who hear "are you going to Sand Hill Road to raise money?" and it sounds as old timey as "are you going down to the soda fountain to play jacks?"

Founders don't come to you. You come to them.

The trends are early and venture still operates in much the same way as it has for decades. But every day I see more of the cracks breaking and I think we're closer to a fundamental shift in venture than we realize.

The VC Renegades

While Naked Brands is primarily focused on celebrities, influencers, and creators I believe there is an underlying element of truth that is impacting venture just as much. The reallocation of trust from brands to individuals is impacting the way founders view the types of investors they want to invite into their companies. The influence within venture has progressively decentralized away from the core brand into renegades leveraging the power of their own brand.

Monolithic Brands

For the longest time people thought often of VC funds as “The Firm.” These amorphous blobs that judged you harshly and spit out cash. Just look at almost every pop culture reference to VCs. In The Social Network you don't even see the VCs that Zuckerberg tells off. You don't need to. You know the gist. Long board room. Stuffy suits. Money pushers.

This isn't to say that the individual investors didn't make a huge difference for their companies, or win over founders based on their relationships. But the overall influence that VCs had over the market came largely from the sway of their firm’s brands.

Feudalism

Over the last 10 years there has been a shift in most ambitious venture funds. Funds recognized that the world was getting larger and the types of companies and founders was growing ever more diverse. And a monolithic brand wasn't going to have enough influence to be everything to everyone. So they started to modularize. Open up fiefdoms.

Doug Leone describes the decision Sequoia made to go into China pretty clearly. They decided to hire an on-the-ground team in China vs. starting it themselves, citing an episode of Hogan's Heroes. "We weren't sure someone else would get it right, but we knew we would get it wrong."

You start to see this again and again in different venture funds. The mothership acknowledges its own inability to be everything so they start to appoint nodes. Neil Shen for Sequoia China. Chris Dixon for a16z Crypto. Dan Rose for Coatue Ventures. Some firms start to decentralize decision making to further acknowledge the importance of these nodes.

Renegades

In just the last few years you've seen an increased number of renegades emerging in venture. These renegades are people who know the value of their own brand and reputation. They recognize the fundamental disruption going on in venture and are leaning into the opportunity it creates.

"One of our theories is to seek out opportunities where there's a major change. Major dislocation in the way things are. Wherever there's turmoil, there's indecision. And wherever there's indecision, there's opportunity. So we look for the confusion when the big companies are confused. When the other venture groups are confused. That's the time to start companies." (Don Valentine)

I’d say there is plenty of turmoil and indecision in venture these days. And this change goes beyond "solo capitalists." That model exists, but I think its an over-simplification of what's happening. The novelty of solo capitalists came from single individuals leading larger rounds without the support and resources of a traditional fund infrastructure.

The appeal of a Renegade goes beyond what governance structure they choose. Lee Fixel is a powerful brand, but he also has Addition as a traditional firm with 20+ people. Harry Stebbings has 4 people he's working with. Harry actually founded a traditional venture fund called Stride with a former Accel partner before stepping away from it to focus on his podcast and raising a connected fund, 20VC. The takeaway is not "fund = bad, being alone = good." It's a shifting of the focus towards the person. The influence they have as a renegade. Harry realized he could do more leaning into his own brand than trying to force himself into a monolith.

No one would argue these renegades are going to overwhelm the entire established venture community. The "kingdoms" of Sequoia, a16z, etc. are still powerhouses that aren’t going anywhere. But renegades exist in the ecosystem with them. They're not after-thoughts like regular angels that VCs might entice into a round to add flavor. They're frenemies that can contend for deals.

VC renegades have emerged from different backgrounds, whether from traditional celebrity (Serena Williams, Ashton Kutcher), new media (Harry Stebbings, Packy McCormick), operating roles (Elad Gil, Josh Buckley, Lachy Groom) or spin-offs from traditional funds (Lee Fixel, Katie Haun, Dave Yuan). And I think this is just the beginning of these kinds of investors.

The Magna Carta Moment in Venture

At the risk of leaning too heavily into the feudalism analogy I think there will be a "Magna Carta Moment" in venture for some of the existing nodes within traditional venture firms. Quick history ramble (brought to you by our sponsor, Wikipedia). Back in the day (much earlier than the 70’s) kings and queens kept nobles under control with things like taxes in exchange for protection in a hub and spoke model (feudalism). One of the things that broke that model down was the Magna Carta. An unpopular king was pushed to sign a document that initially ensured certain rights to nobles. Over time the Magna Carta has come to be respected as a foundational document for individual rights and liberties.

Think about some of the people you may know or have heard of working in venture firms. They seem significantly better than most of the other people at their firm. Or they have a super power. They can raise billions without blinking. They're the most connected talent partner. They're the most technically respected board member. And you wonder, "what is so-and-so still doing at XYZ fund? They should start their own thing."

Obviously every situation is different but you often see the monolithic brand mothership start to crush the spirits of highly qualified partners. This is even more true of "adjacent partners." People that run data science, talent, business development, engineering, or IR within a fund. They're frequently treated as second-class citizens.

For a lot of these people they'll eventually reach a breaking point and they'll either look for a firm acknowledgement of their own value (their own Magna Carta) or they'll strike out on their own. A lot of the same mentality that has driven an explosion in new companies getting started (controlling your own destiny, pursuing your own vision) will also lead people in venture to try and make it on their own.

Who Wins in the New World of Venture?

A lot of the people who stand still long enough to listen to me rant about this are quick to say, "maybe individual brands are garnering more power in early stages but they won't compete with large multi-stage firms." But again, this isn't about solo capitalists who can only swing so hard. Renegades will show up in all shapes and sizes. Their ability to win deals will depend on the value of their product.

There is no shortage of complaints about VCs asking how they can be helpful and then immediately taking to twitter to congratulate themselves before you've answered the question. But there is plenty of criticism for the value-add of super angels too.

For every unhelpful VC there is a story of an investor helping to make a game-changing hire or introduction. There is no binary yes or no answer to the question "are your investors helpful?" It's all a question of the quality of the product any investor can offer.

One thing I'm confident of: the funds that don't wake up and reevaluate their people and their processes are going to really struggle. There is a lot of under-appreciated talent trapped in these monolithic brands, be they folks focused on investing, talent, or bizdev. And there are a lot of funds that think their processes are cutting-edge while they’re simultaneously losing because they're too slow, too conservative, or not communicating any value.

Every firm is a product. They have a collection of SKUs. They need to ask if they have good product-market fit. Because if they don't they’ll be in trouble.

How Long is the Long-Tail?

With solo capitalists a lot of people ask the question "will everyone go solo?" And I agree with Sam Lessin, "I kinda doubt it." But again, the power of being a renegade in venture isn't just about being solo. You can choose whatever form works for you. The real trend is that more and more investor's influence is coming from the power of the individual rather than the firm.

"Big funds are absolutely going to have trouble competing for the next generation of investment talent. Now that you don't have to work somewhere big to be 'in the industry' it is way harder to justify going to work for a big investment firm." (Sam Lessin)

Some people are pretty skeptical that anything will change and monolithic brands will continue to run the show. But a lot of those people are also the same ones whose paycheck is dependent on things not changing. "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."

As for me, I'm on the ultra-optimist end of the spectrum. I don't think it will just be a few GPs with big twitter followings that leave their firms and start their own firms that look a whole lot like what they just left behind. I think the world has woken up to the exciting world of venture and they're getting pretty dang creative.

Super angels, celebrities, rolling funds, "investment 'clans' formed by founders, angels, solo capitalists, and influencers", family offices getting more aggressive about direct investing, popular media orgs making venture investments, talent agencies investing behind the people they place, college students and even high-schoolers being enabled to invest behind the most exciting trends, and corporate VCs becoming more effective players.

There is a long-tail of super talented people who may not be the best investor for everyone, but for a specific group they'll be the perfect investor. Think about it like the creator economy. Does everyone want to watch videos of mushroom foraging? No. But apparently there are 3.3M people who do, and that's enough to make a creator like Alexis Nikole Nelson a huge hit. We'll see renegades emerge in areas like climate change, crypto, mobility, consumer apps, healthcare, and every other category. They can't win every deal, but they'll win the deals they've built just the right brand to win.

one of the better things I've read. Loved your analysis

Thanks for a long, good read!

A direct consequence of that unbundling is VC fragmentation. The abundance of players makes it 10x harder for founders to navigate the VC landscape. Hence tools like openvc.app, signal.nfx.com etc.

Also - how will things pan out in a context where VCs overwhelmingly fail to bring differentiated value beside money?

Fragmentation + Undifferentation = Commoditization ?