This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I am not good at playing guitar. That's not false humility. That is an honest to goodness fact. But when you're younger, there is an appeal of the aura of certain activities that can exist regardless of your commitment to the activity.

Did I fail out of guitar lessons? I never took them. Did I teach myself? Never tried. But did I have a guitar that my brother left behind when he went off to college? Indeed I did. Two of them, in fact. And the aura of playing the guitar was too much for me. So my friend and I would often spend hours strumming away at these guitars together.

In our collective imagination we could harmonize and riff, but in reality you just had two dummies strum-a-dumbing on a couple instruments they had no fundamental understanding of. But the magic wasn't in having all the answers, and being perfect at playing. The fun came from being together in a collaborative way, both enjoying the journey rather than the destination.

When I was at Coatue, I had the privilege of working with Matt Mazzeo. He was not only a funny guy and a great human being, he also had an incredible network. I once bought him a golden plunger to thank him for always being to able to unblock us when we couldn't get in touch with a company.

But one of my favorite memories, and something that I still do to this day (and think of him every time I do it) is jam sessions. Reminiscent of my youthful musical collaborations, Mazz was the best at taking what could feel like a formal exchange of information and turn it into a casual meeting of collaborative minds. A jam session.

I was reminded of that this week when I saw this tweet from Terrence Rohan:

I don't totally agree with the sentiment. I think offering help, and opening up to collaborations both have their place at different points in a relationship. But, for me, it also brought back some thoughts I've had about the meme that VCs can often become when they ask the question "how can I be helpful?"

A few months ago I wrote about this same topic and unpacked both why the meme is so poignant, and how VCs really can be helpful, and some of the ways to improve people's perspective of VC usefulness:

Reframe the question to be more specific: "Here's how I can be helpful..."

Conduct a value-add audit to ensure impact

Encourage founders to ask for help

But I found myself wanting to go deeper in thinking about the psychology of venture investors, why they think they can be helpful, and why a little more soul-searching could do everyone some good.

Mistaking Activity For Impact

Sometimes venture investors can remind you of the Joker's dog analogy:

"Do I really look like a guy with a plan? You know what I am? I'm a dog chasing cars. I wouldn't know what to do with one if I caught it. I just do things."

There is a balance between under-activity and overactivity. In some ways, people don't do enough things. When I worked at Amazon, I had their leadership principles beat into me. One that comes to mind in this discussion is "Bias for Action." They describe the principle this way:

"Speed matters in business. Many decisions and actions are reversible and do not need extensive study. We value calculated risk taking."

And I think that is accurate. Too many people quietly strangle their dreams under the weight of their never ending considerations and contemplations. There is power in being willing to move quickly. However, there is equal criticism for "overactivity." In his 1986 letter to shareholders, Warren Buffett described this criticism:

"We should note that we expect to keep permanently our three primary holdings, Capital Cities/ABC, Inc., GEICO Corporation, and The Washington Post. This attitude may seem old-fashioned in a corporate world in which activity has become the order of the day. Despite the enthusiasm for activity that has swept business and financial America, we will stick with our ‘til-death-do-us-part policy. It’s the only one with which Charlie and I are comfortable, it produces decent results, and it lets our managers and those of our investees run their businesses free of distractions."

On the one hand you have hyperactive investors who feel the itch to make trades, make moves, make things happen. Were they good things? Who knows. But we did things. Peter Drucker has a great quote:

“What gets measured gets managed – even when it’s pointless to measure and manage it, and even if it harms the purpose of the organization to do so.”

I swear I heard this story somewhere, or something like it, but I've never been able to find it again to see if I'm telling it right. There is this idea about incentives. Somewhere, a country was trying to incentivize oil extractors to drill more oil wells. So the government said they would pay $1,000 for every foot these companies drill into the ground. But the cost of digging a well is meaningful, and turns out the first 100 feet are much easier to drill than the next 100 feet. So, because the government simply incentivized drilling, you had drilling companies going around drilling 100 foot holes everywhere to collect the easy money.

Charlie Munger likes to quote Pascal in saying "All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone." But the point Buffett and Munger are making is not that ALL activity is bad, but activity for the sake of activity. The same is true for venture investors. Believing that just "doing things" is a measure of success can do more harm than good.

Maybe the greatest example of this is Fast—the one-click checkout flame out. The company raised $120M and between skydiving trips, Hawaii getaways for all the employees, sponsored race cars, and custom-made action figures of the CEO, the company got to the point where they were burning $10M per month when they were basically pre-product. Were they doing things? Lots of 'em. Any of 'em good? Definitely not.

When I wrote about the topic of “let me know how I can be helpful” last time, I talked about this idea of a "value-add audit." And I think that being measured in how you're impacting your companies is a critical piece of the "how can I be helpful" puzzle. One great example of this is what Alexis Ohanian is building at Seven Seven Six where their system automatically generates an overview of what they've done to engage with their companies.

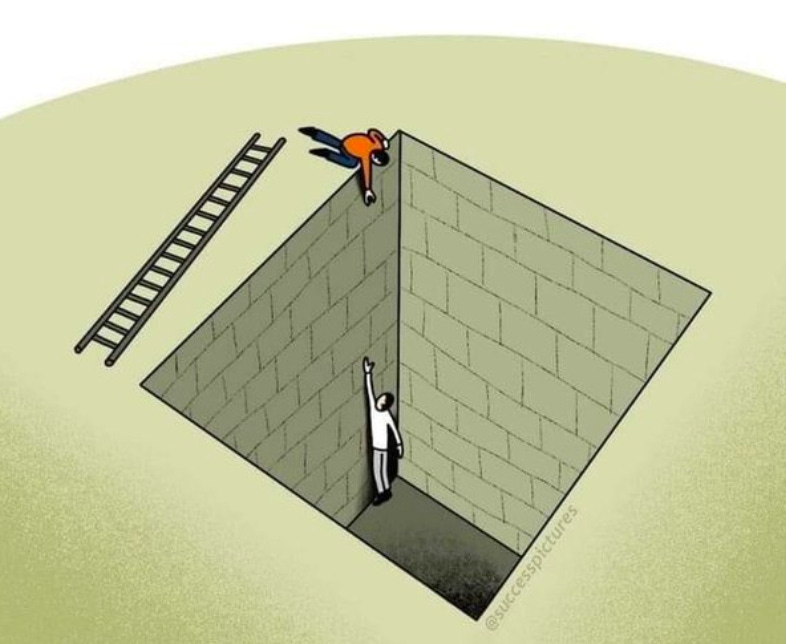

One of the reasons VCs have gotten such a bad name with the "how can I be helpful" meme is not because of hyperactivity, but rather because of a weird mutation of analysis-paralysis. Asking how you can be helpful is so passive, and puts on onus on the founder. Instead, venture investors could provide a more measured view of HOW they can be helpful, and then go about doing it.

Correlating Confidence With Competence

Venture investing is a sort of insane asset class when you think about it. The participants differ wildly, from suit-and-tie asset managers to shorts-wearing hacker nerds, and the approaches are exceptionally different, from cottage-esque micro funds to multi-billion dollar empires. But the majority of venture investing can feel like little more than guesswork, while the outcomes can generate literally billions of dollars in returns.

In one study of managers in different asset classes (e.g. buyout, mezzanine, venture, etc.) the outcome for venture managers? The data is mixed as to whether venture managers seem to "have little or no skill, either in the short- or long-term." One of the reasons I think venture investing has a less discernible skillset than managers in other asset classes is due to the wide variance in terms of what venture investors can do to yield success.

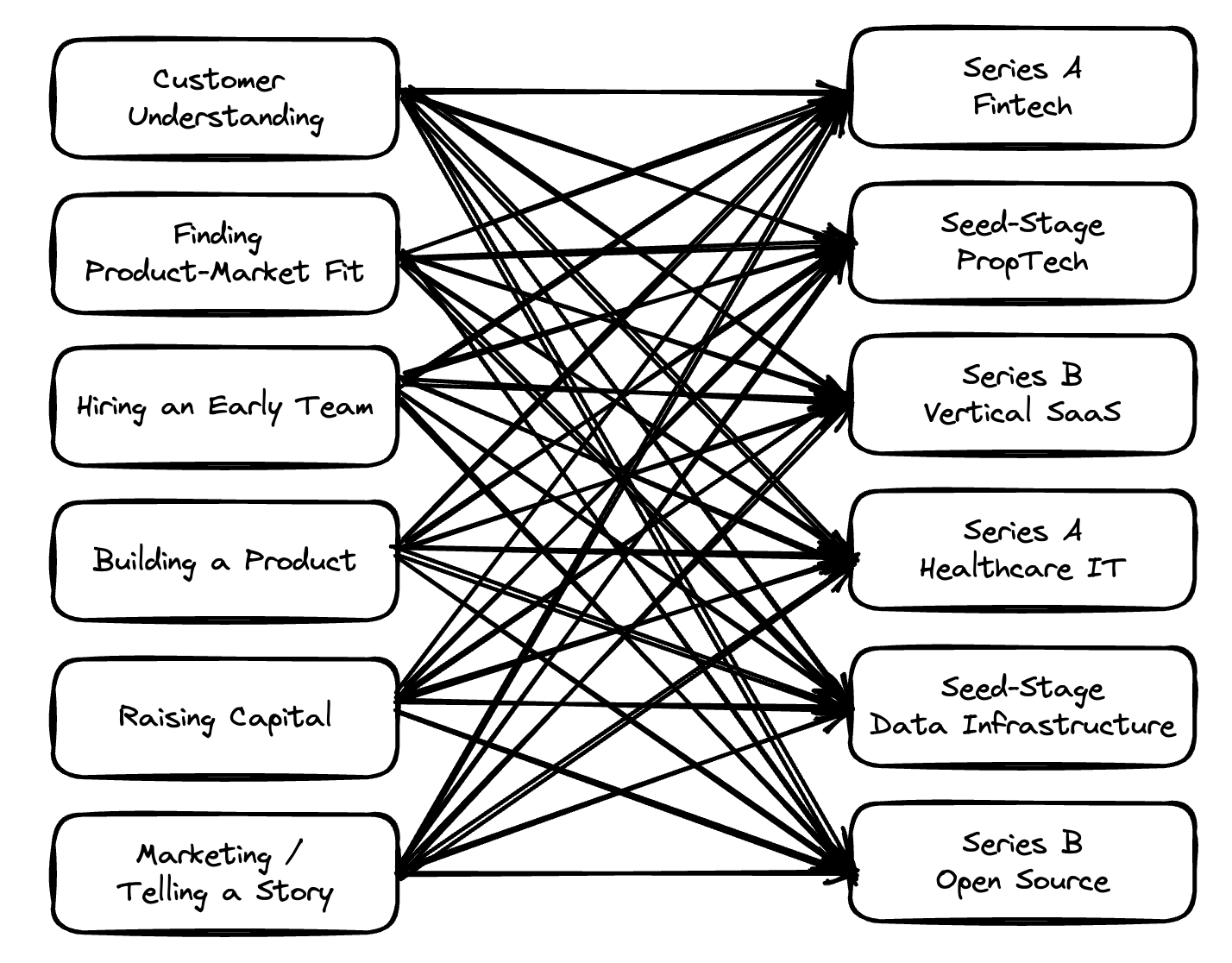

Most private equity firms or stock pickers stay in fairly specific swim lanes and look for replicable companies that fit their checklist. Generalist venture investors are primarily in the business of looking for outliers, so they're spread much further, both in terms of their potential skillset and the type of company they might apply that skillset to.

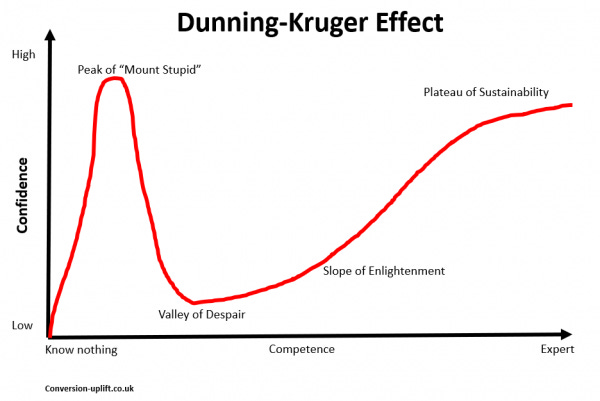

I've written before about how much venture firms want to try and be everything to everyone. But one of the dangers of such a broad set of use cases a firm can offer is that it opens you up to the Dunning-Kruger effect. The main idea is the disconnect that exists between someone who is bad at something vs. how good they think they are at it. The more things you’re doing, the more likely you are to be bad at them but think you’re good at them.

Another framing for this idea is that, at first, when your competence is quite low, you can have pretty high confidence until experience has had the opportunity to punch you in the mouth.

For venture investors who want to be helpful, there is an opportunity to avoid this over-inflated ego of competence. Competence is not a mindset. It is, in the words of Jeff Bezos' leadership principles, "a calculated risk." No matter how capable you actually are (or how capable you may think you are), there is always a possibility that your expertise could lead you and the company astray.

As a result, the best way to be helpful is not relentless gut-trusting, but rather an iterative exercise of data gathering, understanding, hypothesis testing, and reevaluation. Understand if you're helping or hurting, and then tweak the work to ensure optimal support. Wes Kao articulates it best:

The One In The Arena

This brings me back to the jam sessions with Mazz. Something he was incredible at was never coming across as condescending. He's a genuinely good person, and wants to see people succeed. He, to me, embodied the perfect combination of competent, and collaborative.

I've written before about my ideal framework for an investor (as illustrated by an episode of The West Wing):

"The President's deputy chief of staff is frustrated because he's failed to accomplish something. The president says, "the difference between you and me is I want to be 'the guy.' You want to be the guy that 'the guy' counts on." That summed up my desire as a VC."

Founders, men and women, are the ones sitting in the chair. And investors should want to be the person that that person in the chair can count on. One of the ways VCs lose sight of that is, to Terrence's point in the first tweet I shared, to assume "higher status." Because VCs are gatekeepers to capital, they start to breathe in their own fumes, and believe their own hype.

But the reality is that the one in the arena is the most important part of the equation. And some more self-reflection would help investors take a more thoughtful, measured approach to providing support beyond memeified platitudes.

What I'm Reading

How To Be A Good Writer: Amazon Style by Mukund Mohan

Mukund was kind enough to basically write this post for me, encouraging me to improve my writing. I've often been told my writing is easy to read because its very casual, and conversational. That's largely because I write the same way you talk to yourself. But that can also mean that my writing can be rambly and lack a coherent narrative. Mukund's piece helps me think more about the structure I should try and use.

It hides in plain sight by Rudy Havenstein

I stumbled on this piece from a tweet, and its the latest in a long line of instances where, the more I learn about how pervasive Jeffery Epstein's activities were, the more disgusted I grow with how the world works.

Musk Admits Twitter Purchase Wasn’t ‘Financially Smart’—And He Paid Twice What It's Worth by Nicholas Reimann

The acquisition of Twitter is one of the best episodes of Succession we could ask for.

Adobe’s Scott Belsky talks generative AI — and why it’s not going to end up like web3 by Ron Miller

I love it when people push towards making the argument for the practical use cases of AI. What I'm most excited about is not the surface-level "oohs and ahs," but the actual business use cases for these things.

Hunger Games by Ben Hunt

This is the like the bizarro Superman version of Packy McCormick's "Business Is The New Sports." This piece basically says, "oh its a sport alright. A blood sport." This idea of two narratives, the stock market is a great source of wealth, or as a great revolution? Both are suspect.

"Both of these stories are narratives for our very own Hunger Games, a spectacle that chews up the participants in the arena while delivering enormous profits to the networks (media, financial and political) that put them on."

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

so help by collaborating not for the sake keeping yourself busy !

Great piece. It was thought provoking for me. My version of the blanket ask/offer has always been, "please let me know how I may be of service to you." We are service providers, not merely capital providers.

Having said that, I also recognized that ask/offer still puts the onus on the founder. So we always offer support by letting our portfolio companies know the things each member of our team is good at, and give some frames of reference. We each have general skills and specific ones. For example, firing someone? I'm your guy.