This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Stop me if you've heard this one before. Two college students have been studying in the library late at night. On their way home, they stop at a Taco Bell for sustenance. They get home around the time that late becomes early, but they're not ready for bed. So they start to talk.

The conversation begins anchored in practicality. "Why is our roommate incapable of cleaning up their stuff around the apartment?" And then, as surprisingly undeveloped 19-year old brains are wont to do, the conversation turns from the practical into the theoretical.

Our roommate is messy. Is it nature or nurture? Can nurture have any real impact on a person's personality? Is everything simply a natural affect of brain chemistry? What is truth?

Asking what something really is may not only be the most difficult question to answer, but the quickest way to get a tired 19-year old to throw in the towel, finally declaring, "yeah, crazy, huh?" before going to bed. But as a philosophical exercise, there can be value in asking the question of what something is.

Since May 2022 I've wanted to write to try and unpack my thinking in answering the question, "what is an investor?" So let's dig in.

Investing In Investors Vesting Invested Vests

The term "investor" can so easily and often be used to lump a lot of different things together, thinking they're effectively all the same. In reality, your view of what an investor is will typically be skewed by your experience. If you're working at an early stage tech startup, you picture an investor as a venture capitalist. Maybe you've met some hedge fund / crossover folks at a party, but certainly your first thought is not of a bond or commodities trader. Are they investors too?

I've often talked about investing as "the art and science of allocating finite resources to create an optimal outcome.” And I stand by that sweeping generalization. Everyone is an investor of something, because everything has something finite that they're looking to make more of.

Every parent wants to maximize the amount of time they have with their kids, so they invest their time more meaningfully, hopefully making it feel as long-lasting as possible. It doesn't hurt that if you invest in healthy time with your kids, that time will also increase because if you don't suck as a parent, then your kids won't stop talking to you when they're adults.

Diving deeper into the question of "what is an investor?" is more a question of three key things:

What is being allocated?

What is their allocation strategy?

What is the ideal measurement of success?

While I've pointed to everyone being an investor of something, the most common focus is on investors who are allocating capital. Cash. Dolla-dolla-bills. So the answer to number 1 is simple: capital. The strategy is the real representation of investor differences. Let's unpack the matrix there.

Capitalists Galore

First, a caveat. Just like I mentioned before about how people's framework for what an "investor" is typically gets defined by what they're exposed to, I'm guilty of the same crime. I've never traded oil derivatives, and I've never bought self-storage units. So there is a swath of what I still think of as investing that I have a very poor mental framework for. So be gentle in your judgements of my perspective.

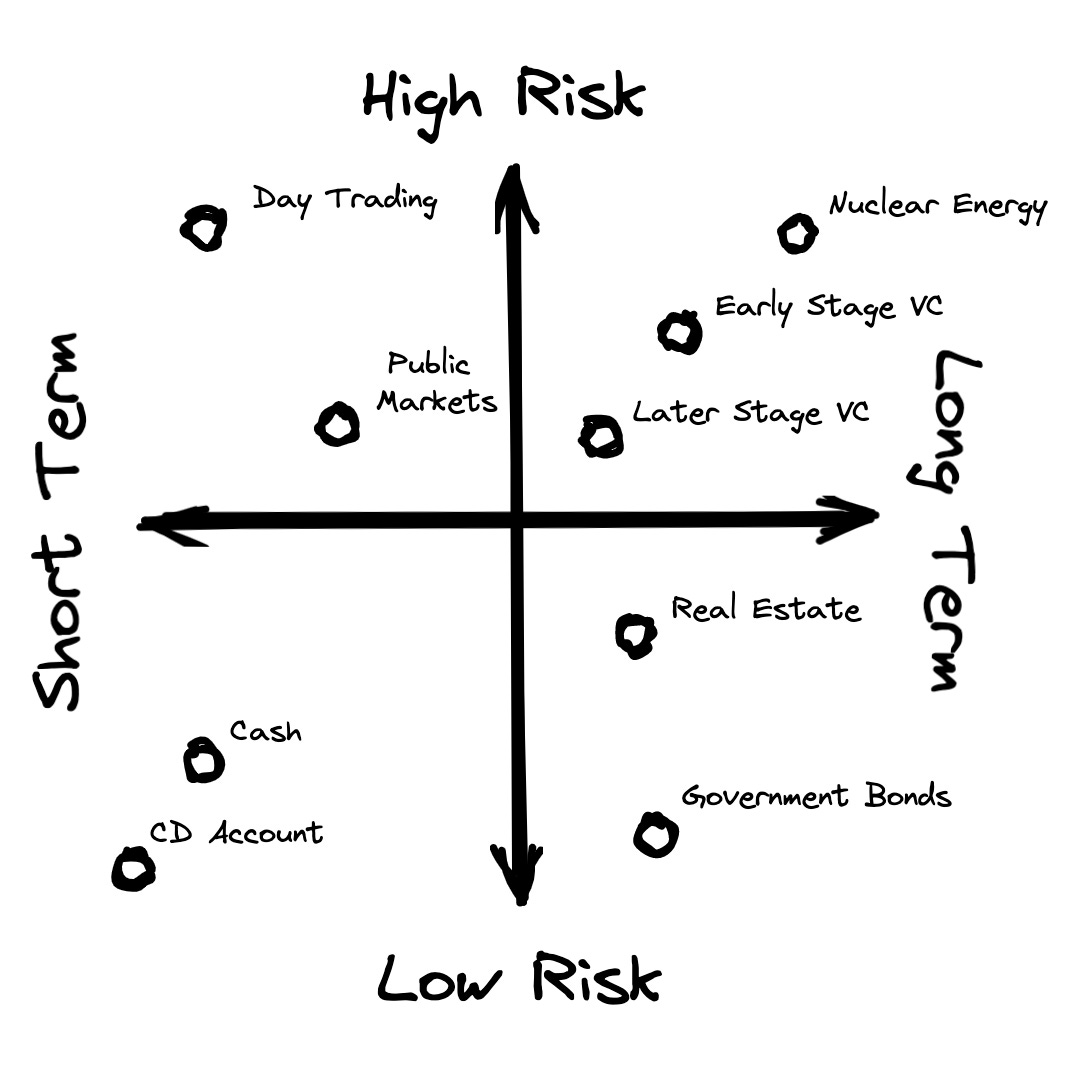

How do I bucket investors in my mind? Every now and then, I have young college students who reach out to wanted to "get into investing." Luckily, some of them have enough familiarity to know they want to get into venture specifically, but more than once the person's goal is simply "investing." Pretty big aperture. Here is how I often frame it for people to help them think about different buckets.

Now, certainly this isn't exhaustive. And every firm investing in one of these types of assets could use a very different strategy. Also, I don't typically use return expectations as the bar of measurement because those differ by strategy. In general, the old rule of thumb holds. Those looking for high risk also require high return to justify the risk.

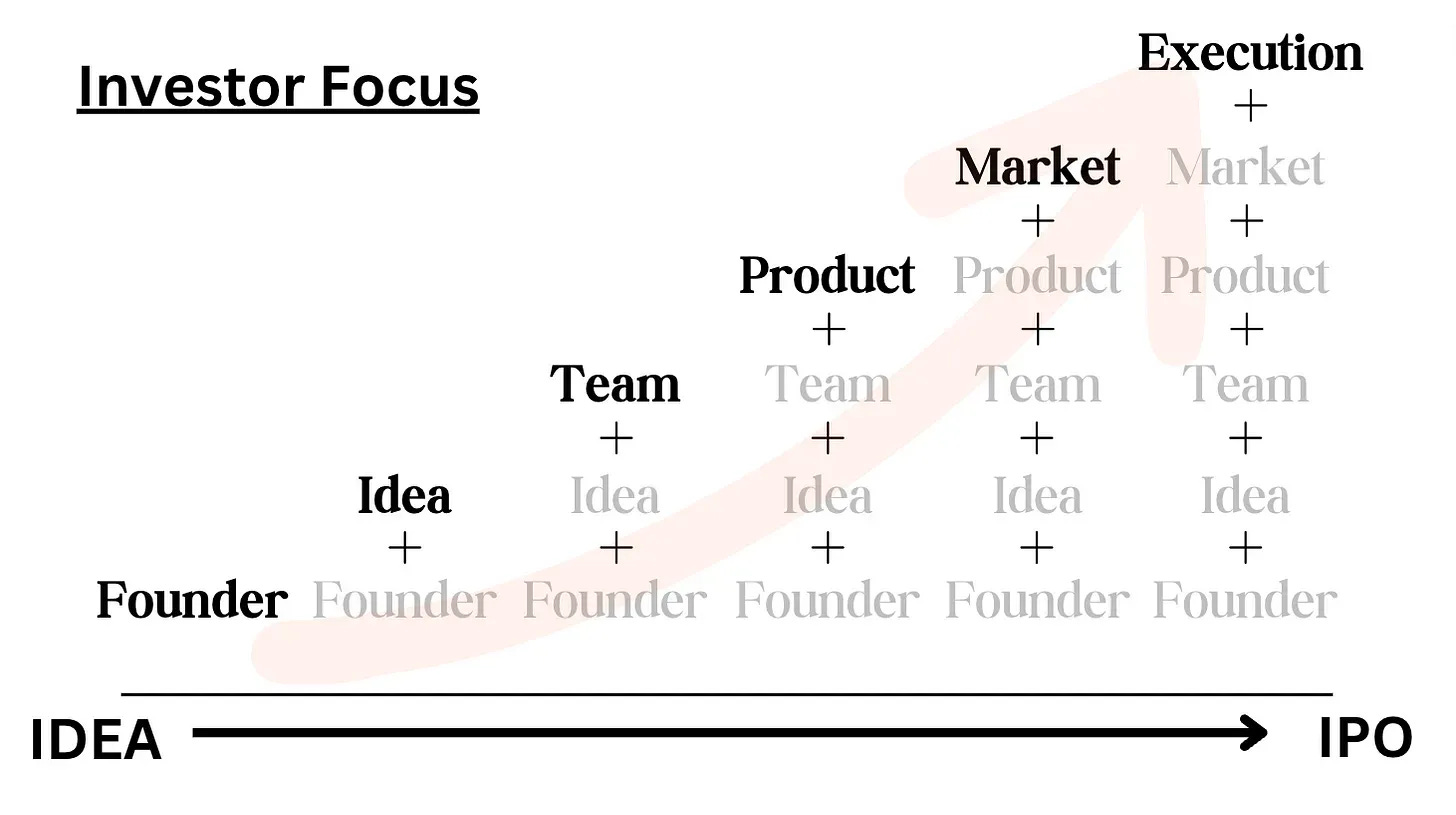

Investors who are getting involved throughout the stages of a company's life focus on different things. I've written before about how they often build one after the other on top of each other.

In the world of investing in tech companies, there are effectively public and private investors, with some nuances in the mix. In my experience public investors are most often focused on "what could go wrong?" while private investors are typically focused on "what could go right?" Let’s unpack some of that.

Crossovers: Rubicon Investors

The first ~5 years of my investing career was shaped by a crossover lens. First, working at TCV (where the firm's full name is literally Technology Crossover Ventures), and then Coatue where, even though I was focused on the private markets, the whole firm was shaped by public market perspective. I've written before about how I think every investor is better off with exposure to BOTH public and private markets.

One key lesson? How to avoid post-IPO blindness as a venture investor. Some venture firms I've worked with feel like they see a company going public as them graduating out of the reality that their startups exist in. Good for outcome benchmarking, but nothing else. In reality, an IPO is just another capital raising event, and nothing more. Every public and private company playing in the same space compete with each other.

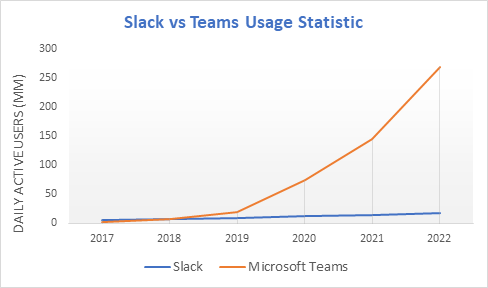

There are few better illustrations of this than any chart showing usage of Slack vs. Microsoft Teams. So many VCs chuckled at Microsoft's boomer attempt to replicate a popular tool. But they did, and they crushed it.

Other people joke about how stupid it is for an investor to ask "what if Google does this?" And to be fair, that's a poorly articulated question. But an even dumber answer is "oh, Google doesn't care about this space." An equally poorly articulated answer.

OpenAI is viewed with a similar, albeit flipped, blindness. Microsoft has invested $10B in the company. As exceptional of a company as OpenAI is, its inaccurate to think of it in the same vein as run-of-the-mill startup building. At this point, it is effectively a Microsoft subsidiary doing quite well in AI. Other AI companies could raise $100M+ and might still be running out of money after ~12 months because their business is so dang expensive to run.

Public investors are much better at understanding the ecosystem around a trend, rather than VCs who are so often focused on which horse they're backing. So while VCs look for the "next OpenAI," which is probably a pretty stupid framework to use, public investors are looking at the bigger picture, not only buying more Microsoft, but they're pushing stocks like Nvidia up 60%+ YTD because of the role their hardware plays in the overall ecosystem of the AI trend.

Venture Capital

There are lots of different ways to think about what it means to be a VC, and peoples views on different types of VCs.

Sometimes people are quick to say, "the only people who should be VCs are former founders." But the data doesn't support that. Sometimes articulating those different types make for great memes, like those from John Vrionis at Unusual Ventures.

Sometimes, people share full white papers on frameworks they've worked out with academic precision that are MECE in a pristine and beautiful way. Not me. This is a random framework I threw out in a 15 minute catch up with a friend. But it encapsulates some of the roles I've seen most often.

Tinkerers: They like to think about the inputs and outputs of business and investing, and how things work. They can go from the 10K foot view all the way down to the weeds on specific comp plans.

Disciple: Often have read Warren Buffett, and are most interested in the art of capital allocation. Often their biggest value add is being a "VC whisperer" because they know how their fellow investors think, and how a company can best appeal to them

Heat Seekers: They love the chase, the competition, and attribute all their excitement to external factors (e.g. how hot a deal is, whose talking about it, etc.)

Josh Lymans: I'll come back to this at the end.

There's no benefit in creating a big exhaustive list of types of VCs and what they do or focus on. In fact, my only point is that there IS a big exhaustive list of LOTS of different types. In my view VCs, even more than public market investors, can come in all shapes and sizes. This is, I think, one of the reasons venture is so hard to evaluate and measure. There are many different ways to be successful, and they can be mutually exclusive.

In one article criticizing some of the failings of venture capital, they make the point that you can't evaluate an entire industry on the anecdotal experience of a few performers:

"If, say, a restaurant chain were underperforming, would we say it’s because the restaurant model is flawed? Or would we not first guess that the restaurant needed to serve better food?"

This speaks to a topic I've written about many times before: the productization of venture capital. One of the biggest shifts in venture, and how venture investors will be defined in the future, will be based on their ability to articulate a uniquely differentiated value proposition for founders. "What is the job that founders hire my money for?"

[Early Stage] Venture Capital

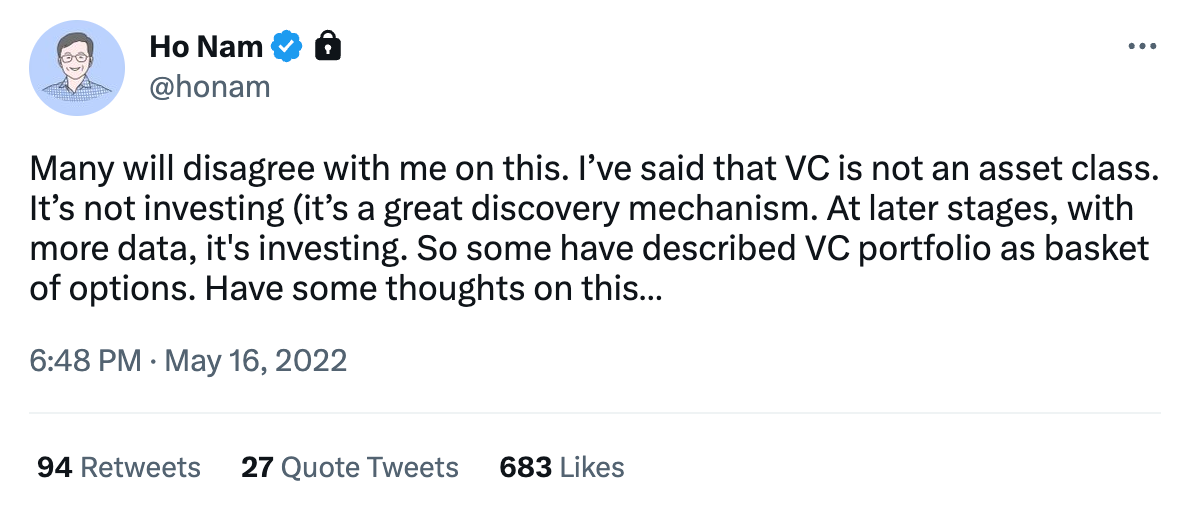

I'd credit Ho Nam with offering one caveat to the investor-types within venture with his response to the question, "what is an investor? Not a VC."

Ho Nam's dislike of comparing venture capital to investing is the humanity that is so inherent to company building. These are people's lives being poured into creating this business. And on the capital side, the focus on LPs and returns that come hand-in-hand with thinking of yourself as "an investor" can be detrimental to long-term value creation.

In my mind, Ho's point is around a frame of mind. VCs do have to think about portfolio construction, and ownership thresholds. But the ones who are mostly focused on that are likely not going to be that successful. The frame of mind that Ho is proposing is measuring success based on value created, not dollars returned. And if you do the first one well, then the second one is likely to follow.

The Venture Capital Success Equation

From the very early days when venture capital was an emerging art in the 1970s, VCs defined themselves by "activist capital." And I don't mean activist investors who make their money by stock swings as they pressure public companies, but rather people who roll their sleeves up with the consumers of their capital.

In a book on the evolution of venture capital, Tom Perkins, one of the early godfathers of VC, and founder of the firm Kleiner Perkins, has a great quote:

"We distinguished ourselves right from the beginning by saying: We are not investors. We're not Wall-Street, stock-picker, investor people. We are entrepreneurs ourselves, and we will work with entrepreneurs in an entrepreneurial way. We will be in it up to our elbows."

The name of that book is The Power Law, named after what many consider the core ethos of venture capital: the idea that one big winner can cover the loses of every other investment in a fund.

First, that quote by Tom Perkins brings us back to our existential college-dorm question of "what is an investor?" According to Perkins, Ho Nam, and others, the answer is "not a venture capitalist." Many of the VC greats have shied away from using the term "investor" to describe what they do. I think this is impacted by both (1) an evolution of the venture market over the last 50 years, and (2) at least in part a component of marketing.

The second point is the less interesting, so let's get it out of the way.

To some extent, avoiding the term "investor" is, in part, a marketing tactic. Founders don't want to hear about their VC's "allocation strategy," they want someone who will get into the weeds with them and help them push this monster undertaking up a hill. But the business model of venture capital is important not to ignore. Should VCs have the mindset of builders rather than portfolio managers? Yes. But would they have a business model if they weren't portfolio managers? No.

Now, for the more interesting point. What is the evolution that's taken place in venture?

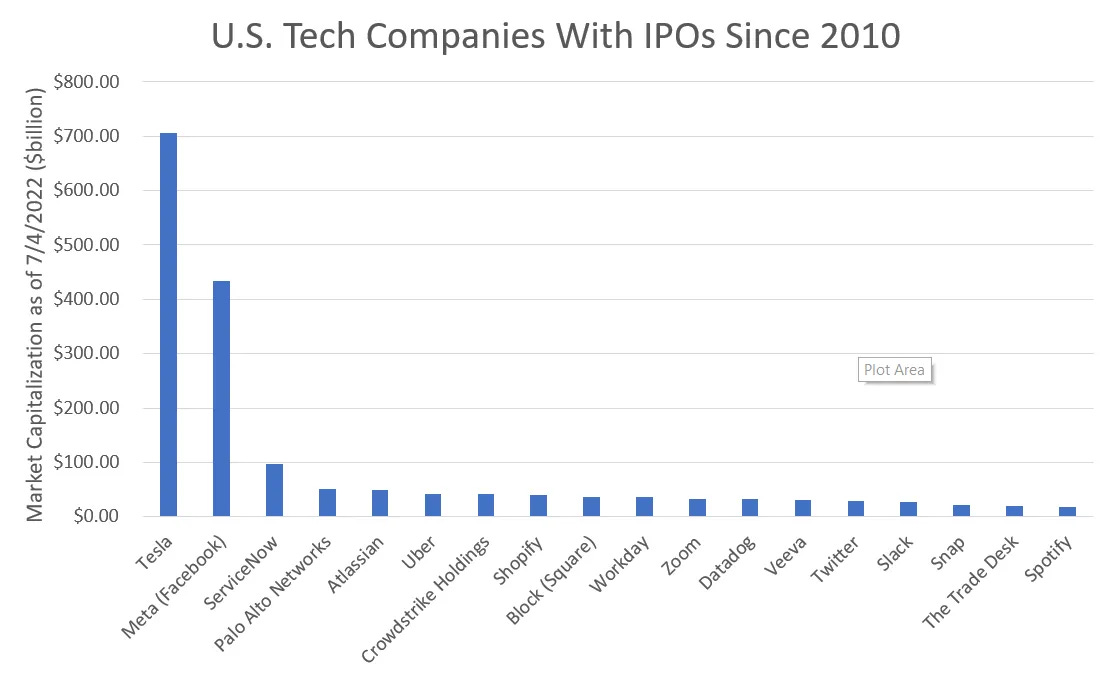

Noah Smith wrote a great article about whether venture will produce fewer home runs in the future. He remembers back to the Facebook IPO in 2012, and when he started wondering "what will be the next Facebook?" In reality, the answer is "ServiceNow, sort of..." It's not nearly as big as Facebook but outside of them, there are very few massive companies that have been created in the last ~10 years. Instead, the outcomes have been ~$10-20B companies. And with the current market correction, that's unlikely to change anytime soon.

The evolution in venture comes from what Noah discusses as "uncertainty" using the work of Frank Knight in making the distinction between risk and uncertainty:

"Knight hypothesized that truly outsized business profits come from taking on true uncertainty. If the probability of success is known, a bunch of gamblers will flood into the space, willing to roll the dice. Risk can be insured and diversified and limited. But if a space is truly a blue-water unknown, then gamblers won’t gamble — only a few bold adventurers will stake their life’s work and their fortunes on something where the chance of success isn’t even known."

Noah then compares starting a tech company in 1975 vs. 2015. The level of uncertainty is dramatically different, and the less uncertainty there is the more competition there is, which drives down the possibility of outsized success.

The fact that there hasn't been a $100B+ venture-backed company (unless you count Snowflake and Coinbase 2021 spikes) brings up the question: does it matter? Venture funds can still see eye-watering returns from $10B companies, why do we care about smaller outcomes? Noah articulates it really well this way:

"There’s the possibility that the establishment of a standardized, routinized VC ecosystem is actually discouraging talented entrepreneurs from doing truly adventurous, blue-sky exploration. Why stake your fortune on a ???% chance of creating a totally new industry and being a $100-billionaire, when you could enter a fairly established space and have a 4% chance of being a $1-billionaire? If the difference between adventurers and gamblers is purely a matter of temperament, then this is no problem, but if America as a whole is moving toward incremental innovation, it might be a problem."

In a rapidly evolving ecosystem, every investor should sit back and reflect on what it means to be successful. In all the conversations I had with folks about "what it means to be an investor," it came down to two core frameworks: (1) the different types of allocators and strategies (everything we've been talking about), and then (2) the role of luck vs. skill. So let's turn to that next.

Luck vs. Skill

This idea of skill and luck comes up again and again in conversations I have with folks. The very first conversation I had with my friend Kevin about this question of what an investor is, we immediately started comparing investing to gambling. Which are more similar? Or more different? It came up again in Noah's article about uncertainty: "if the probability of success is known, a bunch of gamblers will flood into the space, willing to roll the dice." Often, in fields with high uncertainty there is the possibility for not only large outcomes, but for skill to play a bigger role if they can create any advantages.

One of the most recommended pieces of literature on this is Michael Mauboussin's book, The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing. He's given a lot of great talks and written about this concept a number of times. In one summary he outlines it in at least two big parts:

Measuring Performance: "We have a strong tendency to dwell on outcomes without considering the role of process. Take baseball hitting statistics as an example. Some measures, including strikeout ratio, reveal a great deal about the hitter’s skill, while batting average, a more popular measure, includes a great deal of randomness. We need to find performance measures that reflect skill, or elements of the outcome that we can control."

Quantifying Luck vs. Skill: "We need to understand where an activity falls on a continuum from pure skill/no luck on one extreme to no skill/pure luck on the other. For instance, running races are nearly all skill — the fastest runner wins — and roulette wheels are all luck. Everything else is somewhere between the extremities. Quantifying where your activity sits is enormously useful in assessing past outcomes and for making decisions about the future."

People would argue the more exposed you are to the luck end of the continuum, the less of an "investor" you are. But if we're going to dig into the semantics of what an investor is, hopefully I've outlined above how (1) strategy, and (2) outcomes can't be conflated.

Don't Make It Personal

Day traders have capital they wish to maximize. Value investors have capital they wish to maximize. So, if investing is "the art and science of allocating finite resources to create an optimal outcome," then both are investors. What's the difference? The difference is strategy. How do you create an optimal outcome?

And the reality is that people's differing opinions of "what is an investor" often come down to their personal views. And people really do make it personal. The crypto bull market of 2021 is a perfect example of making it personal. People who were NOT making money on crypto took it pretty personal.

Similarly, now that crypto and stocks have plummeted, there are a lot of self-righteous investors saying their way is "God's way" of making money. You could insert any investing philosophy onto this meme, and I guarantee you know someone who fits the bill:

But guess what? There is no "right way" to be an investor. There are, certainly, more effective strategies. But strategies are like wigs: in some situations, they're the perfect fit, and in others you find yourself wearing a rainbow bee's nest to your grandma's funeral. Instead, the important thing is to find what works for you. In the words of Josh Wolfe:

"What are the characteristics that make someone successful? Most people would say it's hard-work, discipline, intelligence, passion, and a willingness to take risks. And you're very likely to find that any sample of millionaires has exactly those traits in common. But! You'll also find those exact same traits in people who have tried their hardest, struck out, and gone broke. It's the relationship between risk and reward. And too often, we mistake luck for success and perfect circumstances for personal competence. The fact of the matter is—many extraordinarily successful people (by the financial metrics we often superficially judge success) are just downright lucky. Right place, right time, right people. So the key is to position yourself in a way to maximize your luck. Frequent and calculated risk taking is one way. But you've got to have the self-esteem and confidence to counter the very thing Keynes described when he said, 'Worldly wisdom teaches us that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.' You can't care what others think. Whatever it is for you, go for it."

So what does this mean for me as an investor?

In a recent groan-inducing article, several young VCs were interviewed and compared leaving banking or consulting for a job in venture as being "catfished," now that the market has turned. What they wanted was hot deals, and what they got were cold market maps.

When people reach out to me asking "how to break into VC," my immediate answer is "probably don't." For people who see venture as a proven path towards fame, success, clout, or whatever, they're in for a rude awakening. Someone's motivations for being an investor can come from a lot of different places, but I come back to Noah's quote about "gamblers willing to roll the dice after known risks."

If you're gambling with a career in venture, then that's a bad gamble. Because not only will you probably not do well, you're also unlikely to do good. Doing well being investment performance, and not doing good being doing active harm to the companies you work with.

I started my career as a founder building a creator marketplace long before I knew to call it that, or even to call it a startup. When justifying my work to my mother-in-law, I always called it a project. Partly because I didn't want to trigger her criticisms of my company not being "a job," and partly because I didn't know what else to call it.

I built Sandbox as a way to help videographers, photographers, and graphic designers get jobs. What I loved most about my work was the ability to support these passionate people, and be a resource to them in making their dreams a reality.

After I sold my company, I didn't know what to do next. I described my love of helping be this resource for passionate people to a friend of mine and he said, "Well, that's sort of what venture capitalists do." I didn't know what those words meant at the time, but that was the beginning of my journey into figuring out what I wanted, my "why."

Later, I had that idea embodied by a clip from The West Wing (remember when I said we would come back to Josh Lyman?) You can watch it below, but here's the TLDR. The President's deputy chief of staff is frustrated because he's failed to accomplish something. The president says, "the difference between you and me is I want to be 'the guy.' You want to be the guy that 'the guy' counts on." That summed up my desire as a VC.

I sat in the seat as a founder (albeit my seat was never very big). I don't want to be that person. I want to be the person that founders can count on. Can call. Can work with to increase their odds of success. I want to build my venture firm as a product that expands my capability to do that.

So that's what an investor is to me. But the more important question? What is an investor to you?

Big thanks to Kevin G. for encouraging me to unpack this topic and to Caroline Newman, Zabie Elmgren, and Ben Laufer for riffing on it with me.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

i was waiting to hear which firm Josh Lyman was at and what his best investments were