Discover more from Investing 101

This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Everyone's first car-buying experience should be a hard lesson in negotiation, capitalism, and humility. I had always heard the traps that you can fall into buying a car, and I was laser focused on not getting screwed. The target? A Nissan Versa.

But I wasn't just going to walk in like some chump off the street. I knew two things: (1) dealerships will often offer "interest-free months" to bring in customers, and (2) they're trying to hit quotas, so they get real agreeable on the last day of the month. With that information, I waited.

Finally, February was interest-free month. On February 28th, at 9 AM I rolled in. I had my Dad waiting to answer the phone when I needed outside information. I met the agent, his name was Chris. And the battle began. We saw the car, we started talking pricing. We started talking packages. It was a battle royal. I was writing out amortization tables on scratch paper to illustrate different discounts.

I had my Dad on the phone calling other dealerships nearby. Chris would give me a $2K discount? I'd call and get them to match it. 10 hours later; it's 7 PM. We've gotten Chris down by 25%. We've got another dealership that will go down by over 30%. Will he match it? "Can't do it," he says in defeat.

With that, we rush triumphantly to the other dealership to get our discount. Elated, I'm not paying very close attention to the details. We're wrapping up, and the finance person is asking me a few questions. "Do you want the blah-blah warranty? Only an extra $35 a month" I chuckle to myself, "whats an extra $35? We'll take it." Again and again, bit by bit, death by a thousand cuts.

When all was said and done, and I reflected on my final price, I had wiped out over half of the discount I'd worked so hard to get, without even realizing it. Like I said. A hard lesson in negotiation, capitalism, and certainly humility.

The Questions To Ask

Buying any asset is an investment, whether it's a car, a stock, a house, or dogecoin. The broader question is whether or not its a good investment. The process most people use to determine whether it's a good investment, or not, is called due diligence. When people talk about getting into the weeds, this is what they mean.

The volume and veracity of due diligence can vary widely depending on the kind of investment you're making, but at the end of the day conducting diligence is knowing what questions to you need to answer. There are some "rules of thumb" and "common analysis," but they all come back to "what question am I trying to answer?"

So let's talk about the questions people are trying to answer, the environment in which they're trying to answer them, and why things have gotten a little weak sauce on the diligence front in the last few years.

A Boring Topic With A Lot of Press

Before I get into the meat, it's important to once again pulse check which of you are living under a rock (or living a healthy life not logging onto Twitter, which is the same thing.) In the last few months, the act of due diligence has really come into question on a few large transactions (if you can call the implosion of a crypto exchange, and disappearance of $10B a "transaction.")

The Free Speecher

First, there was Twitter. And boy, was that a roller coaster.

In his attempt to reawaken free speech on Twitter, Elon Musk got a lot of flack for "waiving due diligence," but then seemingly he also misunderstood that he'd signed a binding merger agreement even before he brought up his concerns about bots on Twitter. That felt like a big misstep.

On top of Musk's seeming lack of any diligence, you then had pretty significant capital providers flooding in with the famous promise of "no additional work required."

Some people make the argument that this isn't the same as a typical venture round where none of the information is public. This is a publicly-traded company with all their financials available. Understandable. But somewhat naive. Large private equity firms like Apollo, Thoma Bravo, and others spent $118B in take-private deals last year. You can bet they're doing a lot more diligence than texting their friends, even though the company is public.

The Fraud

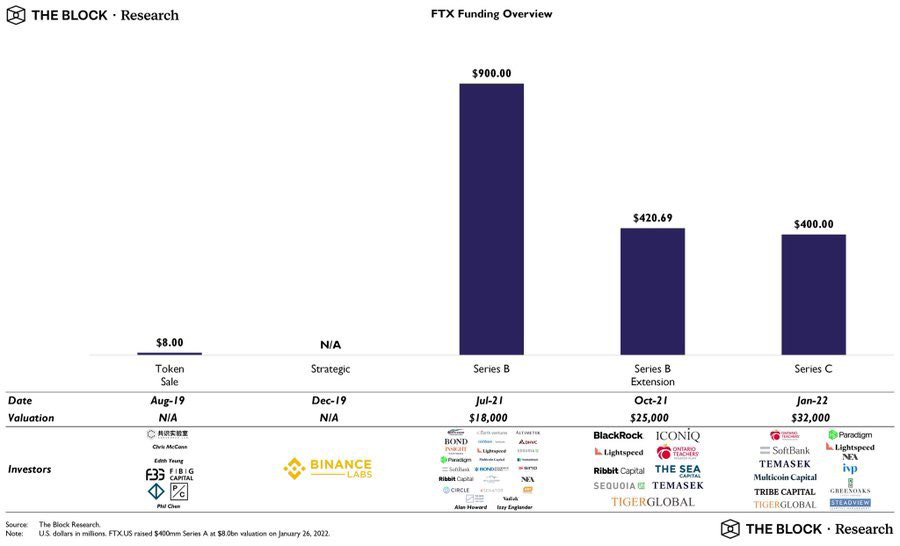

Next, we have the ridiculously well-covered and dramatic implosion of FTX. Most notably, FTX had raised over $1B from some very notable investors including Sequoia, Tiger, Temasek, and a host of others.

A few of those firms have responded to what happened, most notably Sequoia and Temasek. In both responses, these firms claimed to do "extensive research and thorough diligence." Temasek's response, in particular, was quite thorough. They're a ~$300B fund with 900 people investing across asset classes, and would live or die on their ability to conduct thorough due diligence.

"Similar to all investments, we conducted an extensive due diligence process on FTX, which took approximately 8 months from February to October 2021. During this time, we reviewed FTX’s audited financial statement, which showed it to be profitable. Advice from external legal and cybersecurity specialists in key jurisdictions was sought, with legal and regulatory review done for the investments. Separately, we also gathered qualitative feedback on the company and management team based on interviews with people familiar with the company, including employees, industry participants, and other investors. We recognise that while our due diligence processes may mitigate certain risks, it is not practicable to eliminate all risks."

And Everybody Else

These aren't the only isolated incidents of diligence coming under fire. 2021 was a boon for bad behavior, quick decision making, enormous hubris, and misunderstandings around fundamental economic models. Very few VCs are sinless in the "weak diligence" game, but what has been more interesting to me is to reflect on why this happened? Where does diligence go wrong?

FOMO Fever

The last few years have been a whirlwind of changes globally, in technology, and in culture. Keeping up with all of it can be difficult for anyone. The speed of change has created the perfect storm of FOMO for even the most disciplined investors. Regarding the FTX implosion, Jason Zweig had a piece pointing to some of the logic behind what happened to investor judgement in 2021:

"SBF may be at the center of what went wrong, but he didn’t act alone. Behind him lies a vast ecosystem of fantasy and fakery. It’s called the investing business. Despite their vaunted investing expertise, these firms all missed the many red flags fluttering high above FTX. And seldom in financial history have red flags been redder than this. I think the failure comes from what the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge called “the willing suspension of disbelief.” That “poetic faith,” he wrote, has the potential to make the supernatural credible to “every human being.”

Again, this is not something unique to these firms. The last few years provided easy access to capital, and made the act of being in the game more important than the strategy on the field. So while it's unlikely that these firms were doing zero diligence, or engaging in zero oversight, it was often cursory at best.

Ultimately, investors are responsible for their own allocation of capital, and if they're going to give hundreds of millions of dollars to someone playing League of Legends during their pitch meeting, then they can. But they don't have the ability to blame anyone for pushing them into that decision.

When founders take $100M+ in secondary off the table, that is similarly something that ultimately rests on the VCs that allowed their founders to de-risk so dramatically. Founders were operating in a market where there was demand for their stock, and they played the game on the field.

The Game On The Field

Ultimate responsibility falls on the investors who are making these decisions in terms of which companies to invest in, and how much work to require to justify their investment. One important thing to note is the environment that investors have been operating in over the last few years.

I remember when I started in venture, if I saw a company I was interested in announce a round of funding, I would put a reminder to reach back out in 6 months. They probably wouldn't even start thinking about raising before then. Last year? You'd see some companies raise 3 rounds within a 6-month period. Things moved ridiculously fast.

One recent story from the FTX insanity strikes a chord for a few reasons: (1) the data evaluation process in venture due diligence is riddled with obstacles, and (2) deal dynamics can hide a multitude of sins.

Data Evaluation

In an article by Fortune, the journalist got access to two spreadsheets that constituted part of the "data room" FTX had provided investors.

"I spent nearly two days pouring over the FTX documents, which were very unorganized and complicated. The spreadsheets are a far cry from audited financials; rather, they appear to be homespun Excel files, which are at times confusing and have inaccurate labels."

Anyone who has spent time doing diligence in venture knows exactly what they're talking about here. Every company is unique in how they compile their data, and in an even faster-paced world like 2021, venture firms will often take what they can get.

If a messy and disorganized spreadsheet is what the company is willing to offer, you might have a follow up call to ask questions, maybe get a few more cuts of that data, but you don't usually have months to go back and forth into the weeds because you know there are 11 other firms looking at this same company, likely moving faster than you.

The concern is always that fundraising takes a lot of time and effort away from the founder, but the reality is both founders and investors could do a LOT better job making sure the diligence process is thorough. Even if that means taking more time, and putting more work into the process vs. just what's passable.

It's also important to note that even if you do try and go deep, if a company is choosing to be deliberately fraudulent it can be pretty difficult to tell without conducting audited financial checks (which most large venture firms don't do.)

Companies like Headspin raised $100M off of made-up financial statements. I remember hearing stories about their data room, and how suspect things were. They had financial spreadsheets where all the numbers were perfectly round 🧐.

Deal Dynamics

The other aspect you see in that Fortune piece is a "not great" aspect of a lot of the investments that got made over the last few years.

"But whatever investors saw, there was a clear lack of oversight. None of FTX’s big-name backers received board seats. We do have some idea why this happened. One executive, who declined to invest in FTX because the valuations didn’t make sense, pointed to how the exchange raised their rounds. FTX often did not include a lead investor, meaning investors would get very small stakes. “You don’t get a board seat for 2%,” the exec said."

Several people have pointed out that, while investing $200M+ feels like a lot of money, for firms like Sequoia managing $80B+, it represents less than 1% of AUM. And then you factor in that the investment also amounted to owning less than 1% of FTX.

This is a dynamic that was played out literally hundreds of times in 2021, but just done at a ridiculous scale in the case of FTX. "Party rounds" often lead to lots of flashy names, but with no one player having enough skin in the game to do the hard work of ensuring oversight and controls.

And it's not just a function of ownership. Even firms who own 10%+ of a company, they're looking at investments right now that are likely dramatically underwater given current market dynamics, and many of those companies are unlikely to ever live up to their valuations. Which means those VCs will never make money. So is it better for them to dedicate immense time and effort supporting their losses? Or focusing on their next potential winners?

If you raised a round at a $1B+ valuation for <$10M ARR in 2021, and your VCs have stopped being as responsive as they were in 2021, you probably have dead weight on your cap table.

Where's The Focus?

Firms like Tiger Global started responding to this speed by paying hundreds of millions of dollars to Bain for consulting engagements where they could simultaneously run diligence on dozens of companies at once. And that work can be quite good; I've seen the output both at firms I've worked for, and in co-investing with firms like Tiger where they'll share the work they've done.

But often, the trickiest question to answer doesn't come from the outside-in view you can get from market surveys, customer calls, and competitive analysis. In terms of volume of work, that can often be 80% of it. Instead, the things that a company will likely live or die by are the 20% that comes from evaluating the internal engine the company has built. Those aspects require investor judgement.

And in a world where firms like Tiger were moving so fast that you heard stories of them not even opening a data room before issuing $100M+ term sheets, that economic analysis was often what fell by the wayside.

Emphasizing The Economic Engine

In 1986, Warren Buffett wrote, in his annual letter, some commentary on his diligence focus:

"If our success were to depend upon insights we developed through plant inspections, Berkshire would be in big trouble. Rather, in considering an acquisition, we attempt to evaluate the economic characteristics of the business - its competitive strengths and weaknesses - and the quality of the people we will be joining."

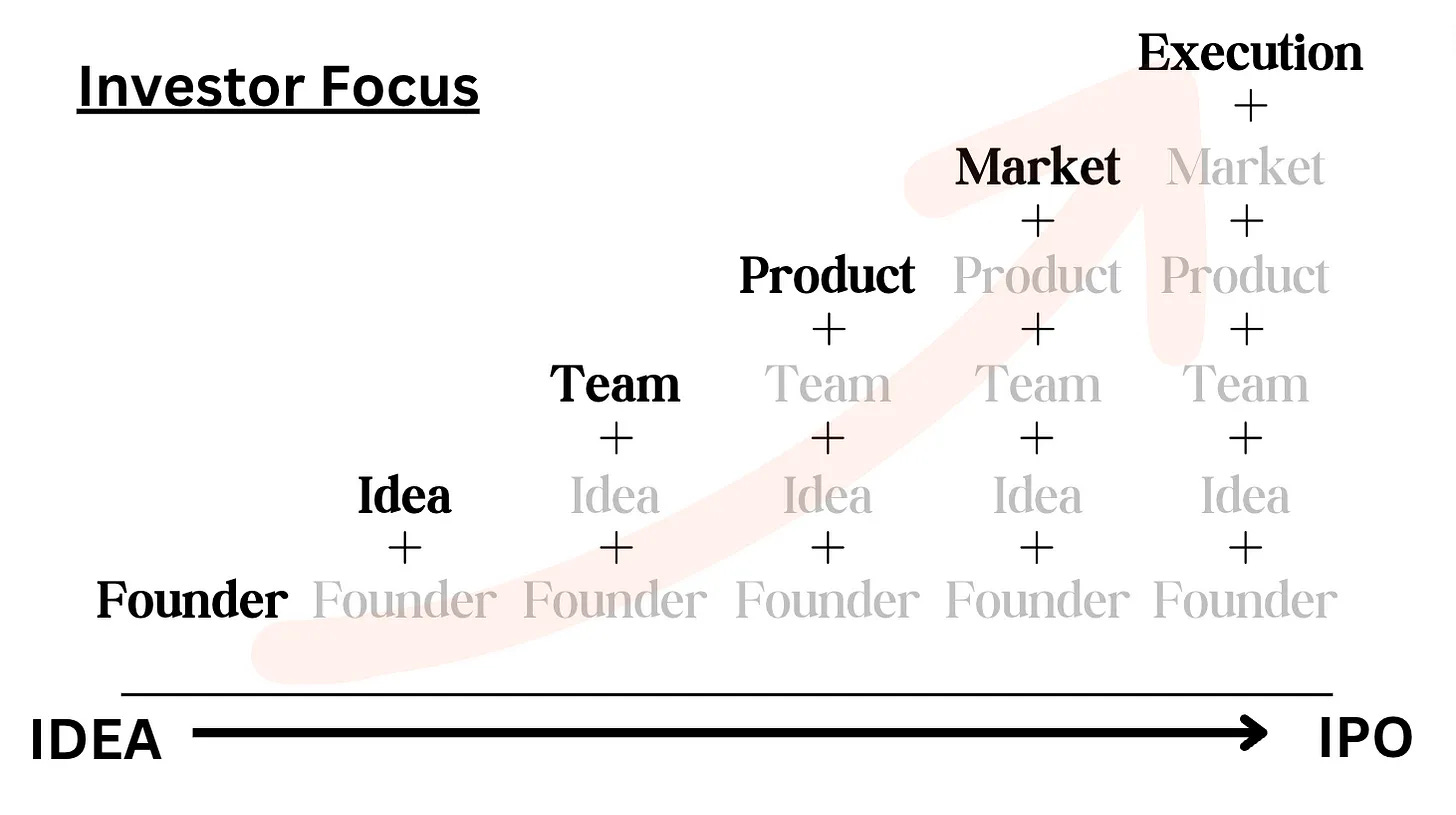

I've written before about this emphasis on understanding a company's underlying economic engine. I've also written before about the different kinds of focus an investor can have as they're investing over the course of a company's life, and how that focus can shift.

So when I talk about the emphasis on an economic engine, I'm not really talking about seed investing. They haven't built an engine. But if you're investing $100M then you had better believe the company has an economic engine, even if that engine is built to just light money on fire to no reasonable end.

And the reality is, there is a rich library of different kinds of analysis that you can do to better understand an economic engine. I think back to the investors I've worked with over the last 7+ years, and I see a myriad of insightful exercises to evaluate a company.

Gross-margin adjusted CAC payback.

ARR segmentation by market, geo, customer size, and buyer behavior.

DAU/MAU based on multi-feature usage.

And the list goes on. When I see companies try and do things like display their net dollar retention (if you exclude customers with <$1M in spend) you see a sort of intellectual dishonesty. The only way that kind of analysis makes any sense, is if you're spending literally $0 to acquire or service those customers.

Otherwise? It's better to unpack the entire story, the good and the bad. Because the reality is those investors are either going to uncover the bad after they become investors, or if they don't then they're probably not the best investors you could have.

What Does This Mean For Venture?

Venture investors could do a better job treating startups like the more professionalized asset class they’ve become, with playbooks and processes that can be consistently evaluated. It shouldn’t just be about finding the Zuckerberg-esque messy genius touting an idea attached to “a total addressable market of every person on the entire planet.” Startups can benefit from more operational excellence, and having informed investors that have seen a much wider variety of models than any one founder typically has. That way, they can push on the good and the bad of any given model.

Rather than having investors who hide their heads in the sand saying "the margins will improve with scale," you need more sophisticated analysts who want to get into the weeds, not just measure the heat that they're chasing.

Founders could do a better job holding their investors to a higher bar. Charlie Munger has this idea about finding a spouse that you can apply to finding an investor: "To find a worthy [partner], be worthy of a worthy [partner]." If you're looking for ways to obscure details, and tell the best picture, then you're going to get an investor who gravitates towards obscured details, and rosy pictures.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Absolutely loving your content Kyle, would you be open to allowing us to share it with our 60k+ audience as well?

Hey great piece!

Including this in Launch House's Homescreen newsletter to 20,000 readers coming out Monday.

We're doing some collabs with VC/founder-writers. Let me know if you ever want to write a short 300-400 piece for LH. Will 100% link back to subscribe button for Investing 101!

https://twitter.com/iamjasonlevin