This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

What's Left?

One of the oft-repeated words of parenting advice I see on TikTok is a way for teaching your kids about taxes and savings. This can be done in one of two ways.

First? When you give them an allowance, you talk them through the exercise of taking a portion of that allowance to pay “rent” or create a “family sharing pool.” Show them how money needs to cover more things than just the thing they wanted to buy.

The second way? When they ask you to help them open a candy bar, you open it and then take a big bite before mumbling, “that’s taxes for you,” and walking away.

I find myself thinking about this idea all the time whenever I dig into the weeds on a company’s P&L. “Oh, so that’s revenue?” Well, actually thats the total platform volume. “Oh, so then revenue is your cut of the volume?” Well, actually we have to pay carrier fees. “Got it, and then revenue comes from that.” Right, but we have all the marketplace take rates to pay out. “So, is that gross margin?”

With a lot of companies, you get down, and down, and down the P&L before all the sudden you find yourself with a very negative number, and a greedy owl that ate your lollipop. “What metric should I care most about?” is not always an easy question to answer.

What's In a Metric?

When it comes to evaluating metrics, investors span a broad spectrum. On the one end? Visionaries and storytellers. People so focused on "dreaming the dream," that numbers are just distractions. On the other hand? Some investors only care about modeling out earnings per share in 2037 for a Series A company, and no one asks the question "what does the company do?" unless it's a part of the broader question, "what does the company do in revenue?"

In reality, there is a much more intricate relationship between a company's story, large addressable markets, and the metrics a company pays attention to that doesn't get enough in-depth thought. In fact, I would argue one of the biggest drivers of excess over the bull market we had for the last ~15 years was driven by a disregard for that relationship between numbers and story.

One brilliant soon-to-be billionaire hedge fund manager I follow described it this way:

“Every business is making orange juice. And they tell their story as if it revolves around the entire addressable market of oranges. But there are different kinds of oranges. And different ways to juice them. But no one does a good enough job laying out the details of their method for juicing specific oranges. Everyone focuses on the headline number of oranges.”

You might be thinking, "but every business is unique. They're not all making orange juice." But if we remove a lot of the fluff, the vision, the impact, and articulate the value of a business in one simple way, what would it be? The discounted value of future cash flows.

In the world of building startups, it can feel overly simplistic to boil a company down to future cash flow. But at the end of the day, every company is trying to perpetuate its own existence by demonstrating that it has a viable long-term economic engine.

Let me double-down on the orange juice analogy. There is an ocean of "spend" in the world that includes everything: advertisers spending to put ads in front of consumers, consumers spending money on products, manufacturers spending money on software, software companies spending money on hosting. That spend represents all the oranges in the world.

But not every orange is the same. Different kinds of spend can be captured as different kinds of revenue. And the process for getting the juice can come with fairly different cost structures. Are you hand squeezing? Single juicer? Mass juicing?

Every business model represents a stick. One end of the stick is revenue. People decide what kind of revenue they want to pick up (Subscription? Pay-for-order-flow? Interchange?) But pretty often, they don't always articulate their story or operate their business with the clear understanding that they have to pick up the other end of the stick: the cost structure.

History Bends Towards Cash

Philosopher, and a man with an ear for cuisine, Mike Tyson once said, "everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face." In the history of taking private tech companies public, usually that "punch in the face" is going public (though that hasn't been as power-packed of a punch for the last few years.) When companies have been telling their story around how many oranges there are without articulating how the juice is made, going public can be a real punch to the face.

In 2011, Bill Gurley wrote a great piece called "All Revenue is Not Created Equal" where he lays out the case for how companies are evaluated. He makes the same case for (in a perfect world) being able to evaluate companies based on the discounted value of future cash flows (usually using a DCF analysis).

"The problem is that it is nearly impossible to predict with any accuracy what the long-term cash flows are for a given company; especially a company that is young or that might be using an innovative and new business model. Additionally, knowing what long-term cash flows look like requires knowledge of a vast number of disparate future variables."

Because the future cash flows of earlier stage companies are so difficult to predict, Gurley lays out a number of variables that can be evaluated instead, because they usually correlate to a higher revenue multiple. Things like competitive advantage, network effects, high switching costs, and more. It's a great read. But the underlying assumption of Gurley's piece is NOT "cash flow doesn't matter, so focus on this stuff instead." These are things that are typically indicative of future cash flows.

But over the last few years, a lot of people lost the big picture. Growth is good; not because it's the only thing that matters, but because it's indicative of future cash flows. Gurley puts it this way:

"While growth is quite important, and even though we are in a market where growth is in particularly high demand, growth all by itself can be misleading. Here is the problem. Growth that can never translate into long-term positive cash flow will have a negative impact on a DCF model, not a positive one. This is known as “profitless prosperity.”

In the late 1990s, when Wall Street began to pay for “revenue” and not “profits” many entrepreneurs figured out a way to give them the revenues they wanted. It turns out that if all you want to do is grow revenues, with disregard for the other variables, it is quite simple to “manufacture” awe-inspiring revenue growth. To prove the point, consider this oft-used example from the Internet bubble. What if I had a business where I sold dollars for $0.85? What would my revenue growth look like? Obviously, you could grow this business to $ billions in revenue tomorrow. While this may be tongue in cheek, the real world example of the “dollar for $0.85” metaphor is any business where the value transfer to customers and suppliers and employees cannot be sustained at a positive profit."

There are two key takeaways from this idea for me that I think haven't gotten enough attention, and it's why the market correction, and focus shift to profit, is so shocking to most people who have only operated in a bull market.

First: Not only is all revenue created equal, but each comes with a very different cost structure at the other end of the stick.

Second: Not every cost structure will eventually turn into 80% gross margin subscription revenue; some cost structures will always turn out very little juice.

Lets dig into the first one... first!

Different Kinds of Oranges

So let's go back to our orange analogy. A business that focuses their entire story on the global pool of oranges is trying to paint a picture of a large addressable market. They might articulate their particular orange of focus (revenue) as a huge opportunity. But what if that orange of focus is a seville orange that is infamous for being bitter? (Man, this analogy is really pushing me down the orange rabbit hole.) To Gurley's point, "not all revenue is created equal."

CJ Gustafson did a great job laying out different kinds of revenue a few months ago. Here's a quick snapshot of just how broad the universe of oranges can be:

Subscription Revenue (monthly, annual): Zoom, Miro, Datadog, Notion, Adobe, Figma, QuickBooks

Transactional Revenue (take rates, interchange, interest, FX): Stripe, Adyen, Airbnb, Uber, Substack, OpenSea, Coinbase, Patreon

Usage-Based Revenue (volume tiers, pay-as-you-go): Snowflake, Twilio, AWS, Digital Ocean, MessageBird

Advertising Revenue (per ad, per search): Snapchat, Indeed, Linkedin

One-Off Revenue (e-commerce purchases, consulting, in-app): Roblox, Strava

Subscription revenue has been held up as the gold standard because it’s more predictable. But again, every company picks up one end of a business model stick (revenue) that will bring with it the other end of the stick (a cost structure). And that relationship is not always apples-to-apples across companies. Just because it's a subscription revenue business doesn't mean it's the same cost structure.

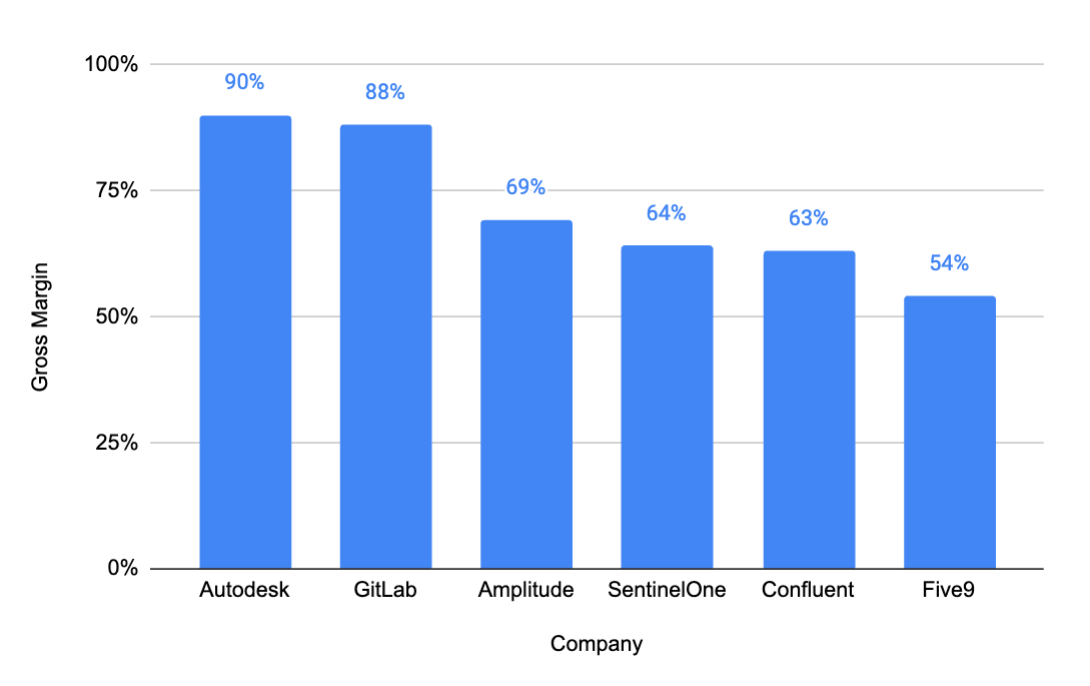

You have software companies that take full advantage of the benefits of cloud computing and have very few costs of serving their revenue, like Autodesk as one random example. But then you have folks like Five9. What's different about their structure? Tomasz Tunguz explains it:

"Five9 provides call center software and telephony software. Five9 buys telephone minutes from telephone companies and packages these minutes with their software so customers can make outbound calls through the Five9 software. The fees Five9 pays to telephone companies is a Cost of Goods Sold."

That same article from Tomasz does a great job of articulating this point: gross profit is often more representative of an apples-to-apples comparison across companies. That takes into account the "other end of the stick" on the revenue each company decides to pick up. People talk a lot about "revenue per employee" as a measure of efficient growth, but in reality a much better measurement would be "gross profit per employee."

We often don't spend enough time talking about those inherent components of a business model. Five9 has to pay telephone companies to connect calls. Twilio has to pay cell carriers to deliver texts.

Fred Wilson took Gurley's concept down the P&L with a piece called "Not All Gross Margin Is The Same."

"An example of that is the Dutch payment processing company Adyen. Adyen operated in the last twelve months with an 18.7% gross margin. Many would think that was a “very low margin business.” But the truth is Adyen is simply passing through that $2.1bn of revenue to financial institutions in the form of interchange and other fees. They do very little with that money."

Tech writers (myself included) often don't do a good enough job articulating these nuances. A decade-plus culture of focus on revenue and growth has pointed all roads towards the glory of subscription revenue, and we've started calling everything a spade. The focus should, instead, be pointed towards the "economic engine" that a business is building. Not just the revenue, not just the gross profit, but the entire engine of how a business translates value for customers into future cash flows.

Is The Juice Worth The Squeeze?

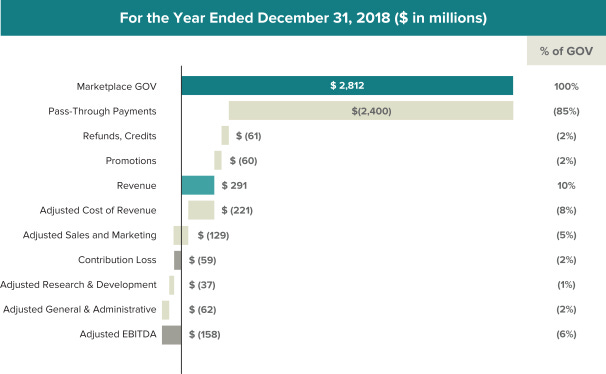

When we talk about an economic engine, there is a massive list of things to take into account for any given business. Take DoorDash as an example. In their S-1 they have this chart where they break down a broad swath of their economic engine, from the entire order volumes they drive, and then take that all the way down to EBITDA.

Understanding what that engine is (and sometimes more importantly, what it isn’t) is a critical piece of evaluating any company and its long-term potential.

The rise of "tech enabled" as an add-on moniker became a way for any business to trade at software multiples. You look at examples like Root Insurance who did everything it could to describe itself as a tech company. Here's their S-1 description:

"Root is a technology company revolutionizing personal insurance with a pricing model based upon fairness and a modern customer experience. The Root advantage is derived from our unique ability to segment individual risk based on complex behavioral data, a customer experience built for ease of use and a product offering made possible with our full-stack insurance structure."

The word "data" appears in their S-1 over 300 times. Great thread here on why this framing of becoming a "tech" company is so important.

So how has that worked out for these companies that try and take a traditional insurance model or real estate brokerage, and techify it? Not great. Companies like Compass or Opendoor are both down more than 75% YTD.

So are all "traditional" companies garbage? Not at all. Title insurance companies like C&F Financial Corporation or First Citizens literally have 100% gross margins. Should they be treated exactly like Root? No, because not all insurance is equal. Not all revenue is equal. Not all gross profit is equal. Not every economic engine is created equal.

Similar dynamics exist in content creation. Netflix and YouTube are neck and neck in terms of revenue, with each generating ~$30B in revenue. The difference? Netflix spent $17B producing content, YouTube pays out 30% for user-generated content.

Is one bad and one is good? Not necessarily. They're different economic engines. Every company will eventually have to answer for the intricacies of their engine, for better or for worse. This is probably one of the most complex points. Companies will often make the argument that at their scale their economic engine will shift dramatically. Burn now, achieve scale, and improve economics later.

And that's not without merit. Around Snap's IPO they still had negative gross margins because the cost to service their massive audience outweighed their revenue. They've steadily improved those gross margins as they've achieved scale.

But some businesses may never improve their engines. That tipping point will be different for every company, and we could all do a better job of articulating that. When we talk about companies with subscription revenue, or interchange revenue, or usage-based revenue, there is a lot of nuance packed into that. And we could do a better job for employees, and investors, and future public markets, to better articulate those intricacies. While markets may ebb and flow in terms of how much emphasis they put on growth vs. profitability, the core thread not to lose is this idea:

"What drives true equity value? Those of us with a fondness for finance will argue until we are blue in the face that discounted cash flows (DCF) are the true drivers of value for any financial asset, companies included."

What Does This Mean For Venture?

The most important concept to take away is how every investor can do a better job of thinking about each company in terms of the economic engine that they're building.

That doesn't mean early stage VCs need to make a seed bet based on the future cash flow generation engine. But at some point, that muscle needs to kick in. Series B? Series C? Depends on the business. But certainly once a company is generating hundreds of millions in revenue, if someone isn't taking a really close look at the underlying economic engine then someone is making a mistake.

When evaluating a potential economic engine, Bill Gurley's 10 characteristics of a future cash generating machine are great. You can use incumbents when possible. People weren't being unreasonable when they would say "Compass is a real estate brokerage, no matter how good their tech is, so what does that engine look like?" Uber is basically like taking a taxi. Airbnb is basically a hotel (or worse, since its like a hotel when you’re the cleaning person). We do need to dream the dream. But we also need to remember that “base” case isn’t supposed to be bull case - 10%. The base case is meant to be the most realistic take you can make.

There is also a lot of first principles thinking that you can apply to understand what an engine might look like at scale. What do payment volumes look like at scale? Text message usage? Data center utilization? Customer acquisition? Early on we all have to dream the dream. And throughout the company-building process there is always a need to dream the dream, and tell the story.

But analyzing a company with an economic engine that is starting to turn is a metrics-driven, first-principles process that more people need to do. And the people who are doing it need to always look for ways to do it better.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Great read. At the end of the day, regardless of what revenue may say, you are what your gross margin says you are.

Great read. I feel like I'm going down a rabbit hole with your articles recently.

I'll read Gurley's article next.

Memo to myself: https://share.glasp.co/kei/?p=SaD15wof34iI2YUZXyWG