The Storytelling of Investing

"The universe is made of stories, not of atoms." (Muriel Rukeyser)

Do you ever have the experience where you watch a movie, or read a book, and you wonder, "how is the whole world not obsessed with this?" The movie gets a 60% on Rotten Tomatoes. The book was on the bargain shelf. Certain stories can resonate with you more meaningfully than they do with other people for whatever reason. That happened to me in 2003.

I watched the movie Secondhand Lions and loved it. Crazy enough, that was almost 20 years ago! And I still think about a particular scene. A young boy is living with his two elderly uncles and one of them has been telling stories of the other's exploits in Africa. The boy is desperate to know from the could-be adventurer if the stories are true. So one night he finally confronts his uncle. "I need to know if those stories are true." I've thought about his response a lot over the years.

"Doesn’t matter if they’re true. If you want to believe in something then believe in it. Just because something isn't true that's no reason you can't believe in it. Sometimes, the things that may or may not be true are the things that a man needs to believe in the most. That people are basically good. That honor, courage, and virtue mean everything. That power and money, money and power, mean nothing. That good always triumphs over evil. Doesn’t matter if it’s true or not, you see. A man should believe in those things because those are things worth believing in."

Some people emphasize the idea that "believing in true things is Good and believing false things is Bad." But I think the world is more complicated than that. You strive to believe in things that you hope are true or in things that are definitively not always true (e.g. good always triumphs over evil). But whether in politics, religion, investing, or anything else—our reality is dictated by the stories we tell. So understanding the ways stories are told is pretty important.

We Are What We Believe

In the book Sapiens, a critical part of any VC starter kit, Yuval Harari makes one of his key points, and a similar point to Secondhand Lions:

”There are no gods in the universe, no nations, no money, no human rights, no laws, and no justice outside the common imagination of human beings. Whether or not something is true doesn’t impact whether you believe it.”

I'm a religious person, and I believe in God. But so do lots of people, and they believe in different Gods than me. So when you start to abstract to only what you can see and touch there are a lot of concepts that feel much more squishy. Google is a corporation. A dollar is worth more than the paper it's on. But money and corporations only really exist because we all collectively agree they do. That "common imagination" Harari talks about is pretty powerful.

In investing a significant part of the process is answering questions like 'what do you believe?' and 'what do you have to believe?' Most people try to be as data-driven as possible in answering those questions, but just like in religion or politics there are mountains of unknowables and so we simply do our best with the information we have.

I've written before about the implications of these collective stories on things like a company's potential and how that translates into a valuation:

"If you had a hedge fund analyst and a venture capitalist on a game show you could ask the question "a company's valuation is primarily based on BLANK." The analyst might say "the cash flows that a business will produce in the future." The VC's answer? "The narrative."

Dan Loeb put it this way in his Q1 2022 letter, "to be an investor is to live constantly at the intersection of story and uncertainty." I spend all day wrapped in the storytelling of investing so as I sought to better understand it I came to focus on two key areas:

(1) The culture of communication. Lots of investment firms and startups alike have built their culture around writing. Learning that skill forces you to understand the fundamentals of storytelling.

(2) The toolkits for telling tales. We use a lot of short hands for telling modern stories. We've traded in cave drawings for pitch decks and spreadsheets. John Culkin said “we shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us." So what are our tools?

The Culture of Communication

Certain cultures have built their organizations around effective communication and storytelling. That focus often emphasizes writing, or what Mario Gabriele has written about as "soft power."

"Soft power acts more gently, like a story. No explicit demand is made of the listener, and as a result, a state of openness is achieved. The content of soft power is more symbolic or metaphorical, enforcing values and norms through narrative."

External content can build soft power. But certain organizations have used writing internally to drive the stories that emphasize their values. Amazon, Stripe, Berkshire Hathaway, Bridgewater. These companies, to me, represent the unique culture of Wordsmiths. I could write an entire post about each individual culture. And in the same way I write Renegade Spotlights about venture firms I plan to write Wordsmith Spotlights to better explore these chronicler cultures.

When you read books like The Everything Store and Amazon Unbound you hear countless stories of writing at the center of how people communicate.

"PowerPoint decks or slide presentations are never used in meetings. Instead, employees are required to write six-page narratives laying out their points in prose, because Bezos believes doing so fosters critical thinking. 'PowerPoint is a very imprecise communication mechanism,' says Jeff Holden, Bezos’s former D. E. Shaw colleague, who by that point had joined the S Team. 'It is fantastically easy to hide between bullet points. You are never forced to express your thoughts completely.'"

Writing pervades the Amazon experience as early as the hiring process where candidates are often asked to write responses to prompts like "the most innovative thing I've ever done" or "the most customer obsessed thing I have ever done in my career."

Not only are major projects written out in narrative form but even decisions like adding air-conditioning units to warehouse facilities require their case written out. In that specific air-conditioning example one executive laid out the argument for installing AC units which was rejected because of the cost. When the media reaction was negative the author-executive was skewered by Bezos. The exec pointed to his original written proposal but Bezos fumed that it had been poorly written, ambiguous, and lacking any details on media reaction or cost savings potential. "[This] is what happens when Amazon puts people in top jobs who can't articulate their ideas clearly and support them with data."

Stripe is famous for high quality documentation, but it's more pervasive than that. David Nunez, the person who spent the last 5 years reinforcing Stripe's writing culture, saw this from the top down. “The first emails I saw from Patrick Collison literally had footnotes." The impact on everyone's thinking is palpable

“Writing forces you to structure your thoughts in a manner just not possible when you verbalize it. When I write, I have to offer structured, precise thoughts.”

So much of company culture is defined by this focus on writing. There is, first and foremost, the internal impact that it has on the people who experience that culture. And within each of these cultures there is an element of discovery occurring in their writing exercises. That's how Jeff Bezos described it:

“You can write down your corporate culture, but when you do so, you’re discovering it, uncovering it—not creating it. It is created slowly over time by the people and by events—by the stories of past success and failure that become a deep part of the company lore.”

Writing in general can have a significant impact on company culture. But in investing the impact of writing—and by extension, thinking—can be even more impactful because the entire outcome revolves around your clarity of thought. There aren't as many incremental product failure points in investing vs. building companies. In investing it's mostly just a question of should you invest or not? And the answer to that question depends on your thinking.

The absolute best argument for this is Mark Seller's Harvard MBA address entitled So You Want To Be The Next Warren Buffett? How's Your Writing? He starts out with a stark reality check: "You have almost no chance of being a great investor. You have a really, really low probability, like 2% or less." So what makes a great investor? It's not reading a lot. It's not a Harvard MBA. It's not even having experience. He lays out seven characteristics that make a great investor; things like obsession with the investing game, ability to stand by convictions in the face of criticism, and others. But the most important?

"Most important, I believe you need to be a good writer. Look at Buffett; he's one of the best writers ever in the business world. It's not a coincidence that he's also one of the best investors of all time. If you can't write clearly, it is my opinion that you don't think very clearly. And if you don't think clearly, you're in trouble. There are a lot of people who have genius IQs who can't think clearly, though they can figure out bond or option pricing in their heads."

Beyond clarity of thought there is a sense of confidence that comes from writing. The more clearly you can articulate your thinking the more trust you can build, both with your investing partners as well as your own investors who are trusting you with their money. Morgan Housel has a great interview with David Perell where he lays out another case for writing in investing (the quote is longy but a goody):

"I think Warren Buffett and Howard Marks were really the forerunners for all of this. They were not just giving their investors more information, but they were using their ability to communicate as a bridge towards trust. And that’s really what it was.

So many investors will say 'Oh I went back and read Warren Buffet’s letters to shareholders and they’re so enlightening.' I think, for the most part, there’s actually not that much technical information in there that most people didn’t already know. If you have a finance background, you understand a free cash flow and value and margin of safety. You get all of that. But Buffett’s letters instilled the sense of like subconscious trust. The way Buffett describes things gives you this view of: 'Hey, you’re not trying to screw me.' Buffett and Marks more or less had permanent capital because their investors trusted them. And because of that trust, all these other hedge fund managers and private equity managers that during a bear market, their investors would have said, “I don’t trust you anymore. I’m out of here. Give me my money back.”

But investors didn’t do that for Buffett or Marks, and that’s a massive competitive advantage right there. So put all that together. Buffett and Marks used content to instill trust, trust gave them permanent capital, and permanent capital gave them a massive financial advantage over other investors.

Newer funds have started to latch on to the power of storytelling, like the recent launch of Mario Gabriele's Generalist Capital: "Narratives move the world. For early-stage founders, an impactful story is magnetic to talent, capital, and customers. Generalist Capital exists to help great entrepreneurs create and capitalize on narrative momentum."

Like I said before, there is so much rich insight to learn from studying Wordsmiths. And I'm excited to dig into that more in the future. To reinforce these cultures of communication there are also tools that drive the narratives forward.

Toolkits For Telling Tales

In the investing world our canvas for storytelling is often investment memos, slide decks, and financial models. The components of these tools are driven by narrative (e.g. investment thesis) and include a combination of numbers (historical and forecasted), anecdotes (customer calls, partnership references), and synthesis (market context around a company or product).

Narrative

I've written a whole piece all about what's in a thesis so I won't go deeper here other than to emphasize that the "narrative" of an investment is about adding context to facts. The storytelling aspect answers the question "why should we care?"

Forecasting

Going back to Yuval Harari, he focuses on numbers. "A person who wishes to influence the decisions of governments, organizations, and companies must learn to speak in numbers. Experts do their best to translate [every] idea into numbers."

Morgan Housel put it another way:

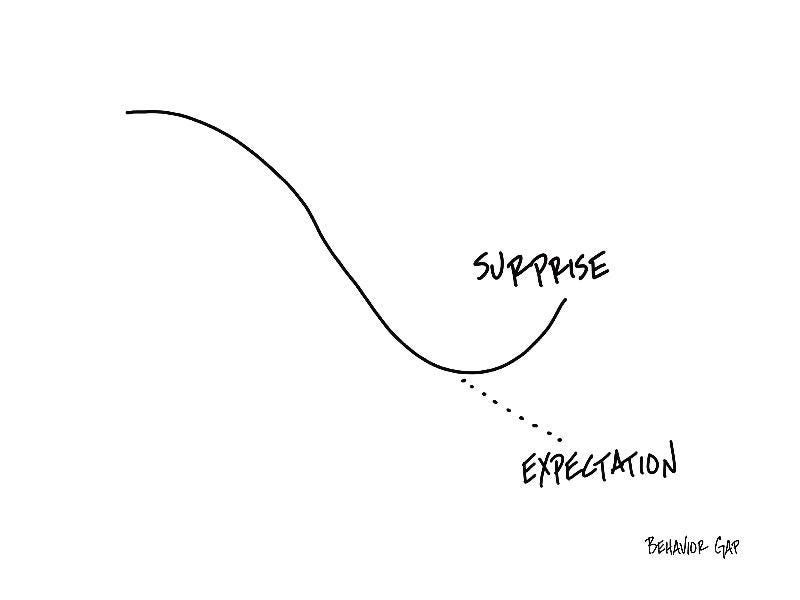

"One way to think about this is that there are always two sides to every investment: The number and the story. Every investment price, every market valuation, is just a number from today multiplied by a story about tomorrow."

But in the world of investing you're entering the danger zone. The world is filled with examples of how very foolish forecasting the future can be.

Sometimes its "fun to look back on" examples of just how much people underestimated great things. Like in 2007 when analysts predicted Amazon would have ~$30B of revenue in 2020 and Amazon went on to generate $386B in 2020. Others leave us in confusion about the state of the world right now. Like when Citi says oil will collapse to $65 a barrel and JPM says it could go up to $380 a barrel.

In reality there is a lot of truth in the words of Warren Buffet: "The forecasts may tell you a great deal about the forecaster; they tell you nothing about the future."

The value of building a financial model and attempting to forecast what a company is capable of provides more value simply from the fact that you do it rather than from the output of the model. A financial model is a physical(-ish) representation of what you believe about a business. How can their margins improve over time? How many customers can they add? Can they derive more value from each customer?

But as soon as you start to believe your "mental exercise" starts to represent definitive reality? That's when you get in trouble.

Anecdotes

Going out and talking with actual customers about their experience or with competitors about how they differentiate or with partners about how they sell a product; these are all anecdotes. They can add valuable context to the overall story that you're telling.

The danger in becoming over-dependent on anecdotal evidence is the often incorrect extrapolation that comes from those conversations. Very rarely can you talk to every customer past, present, and future. As a result you run the risk of assuming that a small sample size is representative of reality and then you're caught off guard. Maybe you talked to the 5 most negative customers and so you expect the company to trend downwards. And then you're surprised.

Synthesis

The danger of being completely story-driven comes from whether you're actually telling a compelling story that represents aspects of reality? Or if you're simply telling yourself a story you want to buy into? In the words of Charlie Munger, "you're the easiest one to fool."

Starting with the narrative, the investment thesis, and then synthesizing the insights you get from numbers and anecdotes is the process through which you form an investment case. Understanding the story you're telling and the pieces that make it up will allow you to better identify the failure points in your own thinking.

What Does This Mean For Venture?

In 1999 Bill Gurley wrote a piece that a lot of people could have benefitted from reading again in 2021. During the run-up in the dotcom you saw an increasing emphasis on storytelling. But the kind of storytelling Bill is talking about is the dangerous kind; the hype-machines that point you to proxy metrics that help spin their tales (the community-adjusted EBITDAs of 1999).

There is a quote floating around in my head that I've never been able to find again. The basic idea is this: "Bad ideas with strong support will often do better than good ideas with poor support." As uncomfortable as many people may be with storytelling impacting outcomes the reality is storytelling is a weapon that can be wielded for good or evil.

Storytelling can quickly become a slippery slope if it's not coupled with significant amounts of intellectual honesty and a spirit of humility. Both of which are things the VC world could use a lot more of.

This is a great read. Here are my favorite quotes:

“You can write down your corporate culture, but when you do so, you’re discovering it, uncovering it—not creating it. It is created slowly over time by the people and by events—by the stories of past success and failure that become a deep part of the company lore.”

"One way to think about this is that there are always two sides to every investment: The number and the story. Every investment price, every market valuation, is just a number from today multiplied by a story about tomorrow."

"Bad ideas with strong support will often do better than good ideas with poor support."

And here's my learning: https://share.glasp.co/kei/?p=T9qGFcZ41jpvA2AG4aZ5

I always think of the following line: "Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?" and I think it echoes true here as well.

You can also see this in the political world. So many movements are driven by narrative, and many times that narrative is actually incorrect/inaccurate, yet people sacrifice so much to advance it and uphold it. Sometimes they discover the facts afterwards, but that does not change the meaning and/or impact of their own work too.

Finally - the power or narrative when it comes to privacy & AAPL, Google, META and TikTok also comes to mind :)

Great article!