This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

When I was in 4th grade, I remember learning what a googol is (the digit 1 with 100 zeros after it). I could see zeros running through my head, and it was hard to conceptualize the number. I remember it so vividly, I could take you back to the exact sidewalk I was walking down after school, trying to understand what that even meant in the context of the numbers I already knew.

More recently, I watched a video that talked about the difference between $1M and $1B. If you earned $1,000 a day every day, it would take 1,000 days (or just under 3 years) to earn $1M. But it would take 1,000,000 days to earn $1B (over 2,700 years).

The power of large numbers is significant. Numbers that you don't appreciate (or as a 4th grader, can’t even conceptualize). If you add a compounding effect on top of an already large number, it becomes very difficult to predict the size of future outcomes.

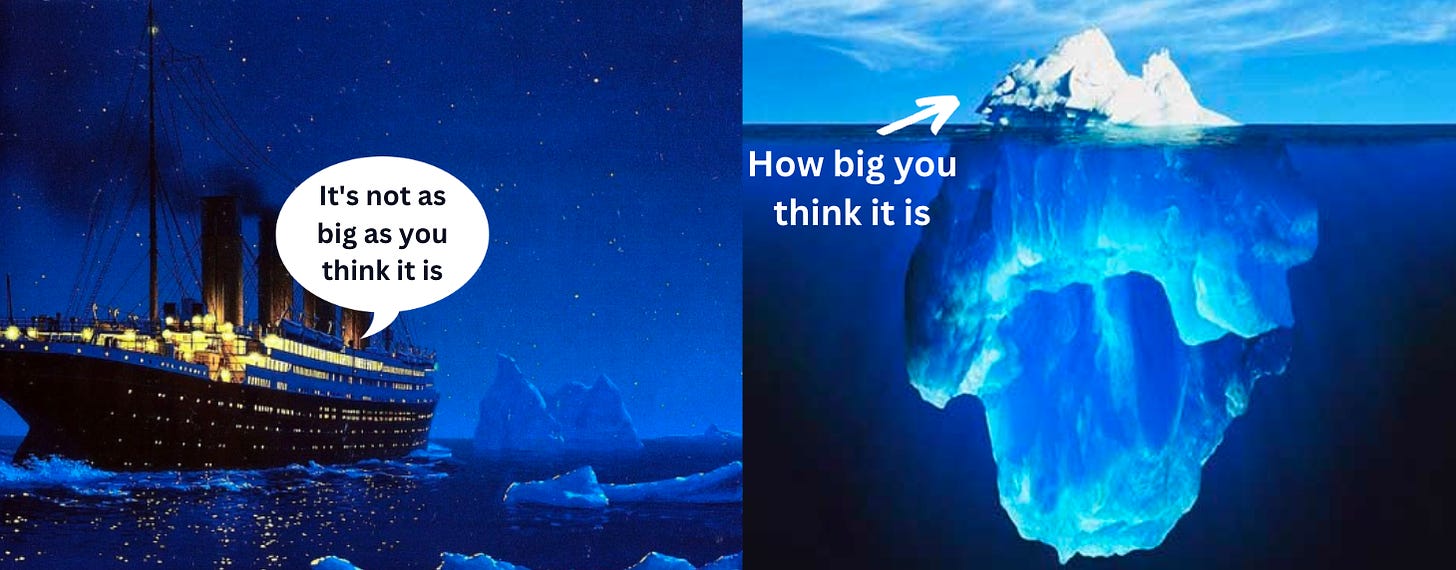

The same can be said of markets. Understanding how big a market really is can be difficult. Market sizing can be an exercise in futility. No one can predict the future. But the act of attempted futurism can have a clarifying effect on your perspective.

Introducing TAM Arbitrage

A few weeks ago, I had the chance to sit down with Harry Stebbings for an episode of 20VC. In it, we talked about the things I'd learned from the venture firms I've worked at. When we talked about Coatue, there was one lesson that has impacted me more than anything else I learned there: this idea of TAM arbitrage.

The core idea is that if you, as an investor or a founder, can do the work and understand a market better than anyone else, and appreciate that its actually bigger than anyone gives it credit for, then investors can pay higher prices, founders can be more aggressive with burn, and experiment more broadly.

Like anything in investing, there are a hundred interconnected variables to a company's success. So just because a market is big doesn't mean you automatically win. Success is also a function of timing, founder quality, and execution. But when it comes to understanding markets, the more perspective you have the more it can give you an advantage.

First, what do I mean when I say TAM arbitrage?

Arbitrage is when you're buying or selling in one market to take advantage of different prices in different markets. For example, if I can buy DVDs of Seinfeld for $2.99 in Palo Alto, ship them to Anchorage, Alaska for $3.99, and sell them for $12.99, I'm benefitting from the fact that Alaskans are willing to pay more for DVDs than Palo Alto...ites.

I've written before about the role that storytelling has, especially in the private markets:

"If you had a hedge fund analyst and a venture capitalist on a game show you could ask the question "a company's valuation is primarily based on BLANK." The analyst might say "the cash flows that a business will produce in the future." The VC's answer? "The narrative."

I use the word arbitrage because we're not talking about different markets in different geographies. We're talking about different markets that exist in different people's minds. If I can fundamentally understand, and believe in, a market more clearly than any other investors then my equation can change in ways that give me an advantage.

Valuation, growth, burn, and ambition are all a function of the size of the opportunity. High valuations, high growth, high burn, and large ambitions are all pretty foolish if the opportunity is small. But sometimes? The opportunity turns out to be so big that it was foolish not to pursue them more aggressively.

First, I want to share some examples of TAM arbitrage that help illustrate the idea. Then, I rightfully have gotten some push back on the concept of TAM arbitrage, so I want to address some of those things.

TAM To Spare

Amazon

Amazon is the example I think of most often, because its not actually some magical event that gave Bezos any unfair advantage. It was simply appreciating the present as it was. I would also argue there were two examples of Amazon's journey that represented an arbitrage opportunity in terms of TAM.

The first? Selling things online.

Bezos was a trader with some exposure to internet companies, but this wasn't a years-long journey of discovery and understanding. This was a dude who read a stat on some random website, and thought "there's something here."

Throughout the Amazon journey there was intense skepticism of everything he was doing. Early on, most of that skepticism came from an inability for a startup to compete with large established retailers.

Granted, a lot of them saw the "death blow" to Amazon coming when the big established retailers started selling online. So while Amazon was born out of an initial appreciation for the growth of the internet, they stayed on top with execution. The ability to execute in an internet-native model vs. the transition big-box retailers were trying (and failing) to execute on.

That wasn't the only big skepticism that Amazon faced. The second? In 2006, they had the idea that there would be advantages to hosting other people's applications and AWS was born. A few years later in 2008, the entire market for cloud computing was a little north of $5B. Today? AWS alone is generating over $80B in revenue.

Again, this doesn't have to be a deep multi-year fundamental understanding of a market. This often comes from an appreciation of reality as it is. The internet is growing 2,300% and it seems to have legs. Building infrastructure is really hard, and we've gotten really good at it. That's how one story describes the early days of AWS in talking to Andy Jassy:

"The company was growing quickly and hiring new software engineers, yet they were still finding, in spite of the additional people, they weren’t building applications any faster. The executive team expected a project to take three months, but it was taking three months just to build the database, compute or storage component.

They realized they had also become quite good at running infrastructure services like compute, storage and database (due to those previously articulated internal requirements). What’s more, they had become highly skilled at running reliable, scalable, cost-effective data centers out of need."

That theme of appreciating reality as it is will come up later.

Stripe

In 2010, Patrick and John Collison started working on Stripe. At the time, digital payments weren't anything to sniff at, with ~$500B in volume. But that was just the tip of the iceberg. Online payments have exploded, ecommerce represents $6T+, and we're still in the early days of online penetration as more transactions move online.

The insight certainly came from appreciating reality as it was, but several companies had already done that. The question wasn't whether people would transact online. PayPal was over a decade old at that point. The insight was how big the market for simpler payment processing online could really be. John Collison put it this way:

“Stripe really did come about because we were really appalled by how hard it was to charge for things online."

Algolia

Jason Lemkin shared this example of his investment in Algolia. The company that provides search-as-a-service was staring down the barrel of a market made up of non-buyers. People would build this themselves.

So how many people were buying search providers? In 2012 when he invested, the company had a $2M TAM. Believing that there is a shift coming in how people buy represents a fundamental bet that you make, believing more people will pay for something in the future than pay for it today.

The Pushback

When Harry shared the clip on TAM arbitrage, there was a great discussion in the comments with phenomenal investors like Ho Nam at Altos Ventures, Mike Maples at Floodgate, Roger Ehrenberg at IA Ventures, and operators like Jason Lemkin at SaaStr and Jon Oberheide, the co-founder and former CTO of Duo Security.

One thing that came up again and again was the focus most of these investors had on the founder.

And rightfully so, most of them have built their success around investing in companies at the earliest stages, usually seed. My career has been more focused at the later stages, and as I reflected on the discussion, I thought of this framework for how an investor's surface area increases as the company progresses.

This isn't to say that execution doesn't matter until IPO. But simply that the surface area of what you have to believe increases as the company progresses. You're often investing more money at higher valuations, so you have to make multiple considerations. At the Series B or C, it's not usually enough to just say "the founder is a visionary," if the product metrics are terrible, the GTM is stalling because the market isn't materializing, and the team is sinking the ship. So the ability to focus on markets and the size of the opportunity often comes as a later stage investor.

People's questions around TAM arbitrage came from questioning who was predicting the future; founders or investors? Can you even predict the future? And do markets ever really change? So let's dig into some of those.

The Oracles of Tech

I'm a firm believer that founders are the people who can predict the future. In large part because of this:

"The best way to predict the future is to invent it." (Alan Kay)

As an investor, you can try and find founders who are predicting the future. I've articulated this same idea a different way before. If I could talk to anyone about the future of X, would I call this founder? I'm looking for someone who has positioned themselves to most dogmatically understand the future for a particular industry or technology.

Predicting The Future

So as investors, what's are job as it pertains to the future? Jon Oberheide shared this quote from Matt Cohler that I'd heard before, but really appreciated in this context:

In a Quora AMA, Matt Cohler elaborated on what he meant by that:

"First of all I should clarify that when I talked about noticing the present first, I meant it in the context of surfacing and pursuing new investment opportunities. Once a venture investor is actually working with a company it's critically important for that person to be able to see around corners -- not to predict the future many years out, but to have the experience, pattern-recognition and judgment to know what's coming next and to help an entrepreneur and company make good decisions by making use of that knowledge."

I think there are two skills articulated here:

See the present very clearly (Bezos appreciating the internet growth for what it was, or the complexity of setting up infrastructure)

See around corners in terms of what a company can expect

This approach feels very pragmatic, and I agree with it. See the trends clearly that matter. You're not extrapolating into the future dramatically, you're just being more observant of the reality you're in.

But there is an aspect of futurism that I think more investors could benefit from. Thoughtfully imagining the future is what all investors are doing, whether we like it or not. Michael Dempsey puts it this way:

"We help companies build, survive, and scale, but one of the main components of my job is understanding how and when the world is going to change. Our portfolio is a collage of various futures that we believe in, and our capital and expertise are assets to hopefully pull these futures forward."

I don't think of this as an affront to the idea that "no one can predict the future." It is, instead, a statement of belief. You're putting your capital and resources behind a future you believe in. Will Bezos' 2,300% internet growth be long-term? Or more volatile, like OpenSea's NFT volumes?

I like this framing from Mike Maples: "dominating the present with insights."

TAM Execution

The final question is whether "TAM dreaming" can translate into dollars and cents in terms of valuation and execution. It's fair to say that none of the futurism we've talked about thus far is grounded in any precise science. Forecasts have only one thing in common; they're all wrong. But appreciating directional size for a market can impact the equation.

Often, companies are underestimated because people believe the market isn't large enough, and the execution will have risks. Look at Crowdstrike. When they went public, a combination of TAM hesitations and execution risks pushed analysts to estimate their revenue potential in 2022 (3 years after IPO) as being sub $1B in revenue. Now, they're trending towards $2B in revenue.

So how does that translate into the valuation I can pay today? If you have a fundamentally different belief about the size of the market then you believe that the company will be able to address more customers, and generate more revenue.

Take Figma as an example. One of the biggest skepticisms of Figma was the comparison of the product design market to something like the market for software engineers. There are over 3M software engineers in the US compared to 70K product designers.

The "future" that those skepticisms doesn't take into account includes the growing importance of design, the increasing number of companies building software, the collaborative role that engineers, marketers, and ops has in design. All of those things are aspects of the future someone believes in who believes in the potential for Figma beyond a per-seat license for 70K designers.

What Does This Mean For Venture?

Like everything in venture, there is no ONE reason any investment works. Every company is a complex web of variables. But when considering the opportunity in a market, it's important to be willing to dream big.

Think of it as a dream exercise around value creation and value capture. Are there more people who would benefit from this thing than you might initially expect (e.g. Facebook becoming more than just a college network)? And is there a model for capturing more and more value?

Early on, big things might start out feeling like a toy. But their ability to extend from one value proposition to the next, and address more and more of a market is the secret sauce you want to dream about. That's where high net dollar retention comes from. Companies that are able to drive usage (more volume of the same thing) or modules (adjacent pieces of the same thing) will find themselves with more more market to address.

As VCs imagine the future for any given company, take the time to go through that exercise. Talk to the founders and operators who understand that market most intimately. What do people believe will happen? What could they be wrong about?

Dream the dream vividly.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week: