This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

If you've read enough of my writing, you'll know that the majority of my personality and frameworks for my life come from movies. I'm obsessed with stories. When I sat down to think about courage, two stories came to mind.

The first? A Hobbit's tale. Bilbo has this moment before he sets off to join the company of Thorin Oakenshield, where he feels briefly relieved that the dwarves are gone. But before he realizes it, he's racing across the Shire to catch up. That moment reminds me of a quote from Bilbo Baggins that comes from The Lord of The Rings instead:

“It's a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don't keep your feet, there's no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

Second, a favorite from Night at the Museum. When Teddy Roosevelt tells Larry Daley that it's time for his next adventure, he expresses his worry that he has no idea what he'll do tomorrow. Robin William's Roosevelt has this response: "How exciting!"

Adventures today are not always grand journeys or great challenges. Often, they are intellectual adventures. And increasingly, many people are content to sit as NPCs letting the challenges pass them by, instead choosing to take the easy way out. Whether you're investing in startups, building companies, working on someone else's something, or seeking to change the world—there are plenty of people who would rather take the easy way out.

A Cornucopia of Cowards

One of the dangers of my writing is that I spend so much time ruminating on similar ideas, that they sometimes blend together. My fear is that particular topics start to contain too many moving parts for me to effectively opine on. But all of these ideas fit together in my head, and the purpose of my writing is to unpack my own thinking. So intellectual cowardice is where I landed.

The variety of different ideas that I'm unpacking started to revolve around some key examples of intellectual cowardice:

Refusing to change your mind, or refusing to believe something radical.

Refusing to accept ideas that go against what you'd prefer to think.

Choosing only to believe hard things once they move into the mainstream.

I Don't Want To Think

I started out thinking about this piece as an exploration of optimism vs. pessimism. But the more I read, the more I kept coming back to the intellectual effort that optimism requires. People don't want to take the time to think about what could happen (optimism), so they default to not thinking at all, or at least not beyond the thinking they've already done (pessimism). And that's not only lazy, but it's dangerous.

When you ask any number of investors why they like investing, one of the most common answers you'll get is due to the "intellectual stimulation" that the job provides. I certainly agree with that. But the amount of intellectual stimulation that is going on can very much ebb and flow.

I've written several times about the incentives for investing, and for venture capital in particular. And in the same way that most venture capitalists are not long-term investors, they're also not necessarily focused on making the best decisions:

"Venture funds, contrary to the marketing framework they like to reinforce, are not long-term thinkers. They’re a collection of short-term careerists focused on maximizing the amount of success they’re associated with. As an individual investor, your economic interests are not as easily connected to long-term success, but instead short-term performance."

As a result of the incentives of venture funds, I'm reminded of the idea that success has many parents, but failure is an orphan. Given the incentive to associate yourself with as much success as possible, while distancing yourself from as much failure as possible, you end up with more of a decision-making committee, each trying to maximize and minimize the good and the bad respectively.

All of these incentives often lead to a group of investors who are not necessarily interested in thinking. Certainly they're not thinking very deeply. Instead, it is easier to criticize the outlandish ideas. As a result, a lot of venture firms begin to consolidate into a committee of critics. David Senra shard this great quote from David Ogilvy about criticism:

"In my experience, committees can criticize, but they cannot create. Search the parks in all your cities; you'll find no statues of committees."

The very best investors are those who think deeply about what the future holds. I've always loved Accel's concept of a "prepared mind." The willingness of people willing to think deeply, and to dream the dream will ultimately allow those same people to see the stars that can be produced by simplicity.

Pessimism will always sound smarter. And it will always play into the hand of someone desperately trying to avoid failure. The constant pressure of conformity makes contrarian optimism nearly impossible. But in the end, the ultimate successes will come from optimism. And optimism is hard work.

I Think What I Think

Often, pessimism is the intellectual wet blank that people wrap around the responsibility to think more deeply about something. I've been in any number of investment committees where people seem physically incapable of changing their mind.

I've argued with older investors who passed on a company at the seed. I try and do the Series A, but they passed at the seed. I try to do the Series B, but they passed at the seed. It isn't until that company is acquired for billions, or goes public, that they suddenly wake up and say "we need to reevaluate our processes to make sure we don't make that mistake again."

There may be no "I" in team, but everyone is desperate to avoid the "me" in blame.

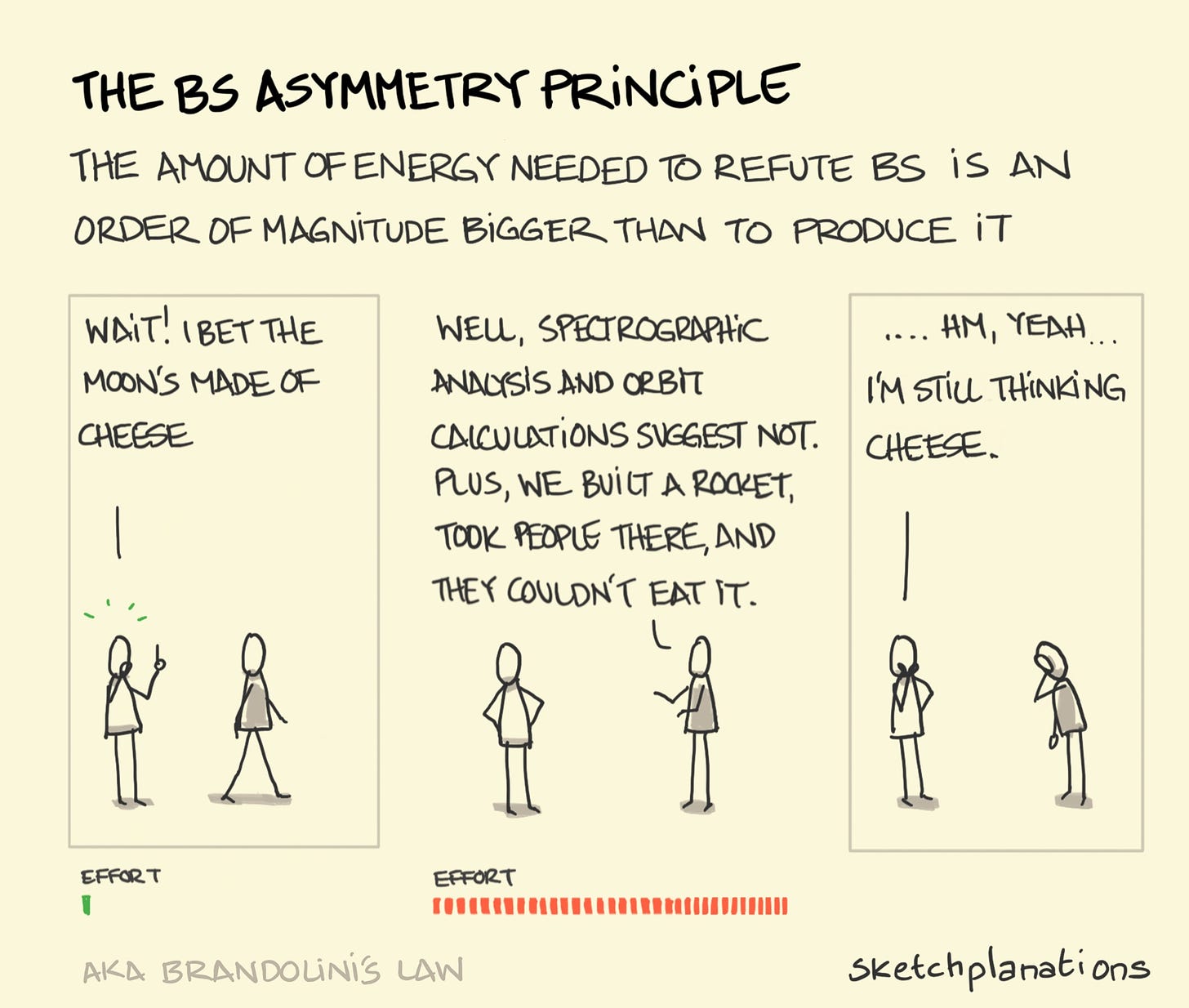

That inability for investors to change their mind may seem more sophisticated because its about capital allocation and long-term decision making. But the reality is its the same brand of BS that you see apparent in education, politics, gun control, and most any other category. The fact is its so much easier to believe your own BS than it is to believe someone else's hypothesis.

In investing, saying "no" to a potential investment isn't super cut and dry. Its a complex web. Sometimes its complex because you've come to an informed conclusion. But other times that web is a mixture of laziness because getting to the right answer requires work, while saying no is much easier.

As an investor, I've had plenty of experiences where I'll do dozens of customer interviews, evaluate product benchmarks, crunch the numbers on a company's traction, and spend hours with the founder, only to have the investment shot down because someone looked at the end market two years ago and it was "too tough."

Deciding to just think what you already think isn't necessarily as lazy as wanting to simply stay negative and avoid thinking. Instead, there is often a significant amount of effort that often goes into people who are convinced that they're right. Their hard work, however, is less an exploration of truth, and more like reinforcing their own beliefs with additional confirmation bias.

Bit of a tangent. I'm a very religious person. The idea of "not being willing to change your mind" can often feel uncomfortable for religious people. For whatever reason, I haven't had a problem with that. I think the ultimate question of "is there a God?" seems to me to be as unprovable as the statement, "there is no God." Instead, I focus my powers of discernment around the details, not the dogma.

I seek to apply critical thinking into every individual decision about how to live my life, what to believe, what I think is critical for my family, and what is the biased opinions of human beings creating rules for no reason but status quo. In every religion, including my own, there are aspects of the orthodoxy that I'm sure their/my God doesn't care about, even if he/she/it is actually real. The philosophies of men, mingled with scripture.

When it comes to religion, I'm more interested in getting to heaven and having God say "you got all the details wrong, but you were the best person you could be. Let me teach you the right details," rather than showing up and having him say, "well, you got all the details right. But you were a terrible person."

For some people, they stand by their existing perspectives aggressively. For others, there is honest answer seeking. Then, there is always the opportunity to say, "I don't know." But that brings with it all its own baggage.

I Think What You Think

Finally, we have the lemmings. These are the kids who, when they asked questions, got the answer, "because I said so," and they loved it. These are the people who, when asked what they want to be when they grew up, responded with "whatever you tell me drill sergeant."

There are so many people that have been programmed to look for the safe answers. The standard path can be so very comfortable, that it makes it impossible to wander outside the intellectual safety lines.

In venture, that can often manifest in the form of the question, "who else is investing?" That's a common enough question that its become a meme of its own. I think that can actually be a more complex question than it first appears. But the more egregious form is the wishy-washiness of the last few years.

There are plenty of about-face bouncers from hot thing to hot thing. I can think of a few recent examples. Since I've already gone on a bit of a religious rant, I'll throw in the way Jesus Christ said it:

"So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will [spew] thee out of my mouth."

I would rather you be cold or hot. I would rather argue with those that have strong opinions for or against. But those who "talk less, and smile more" demonstrate the worst kind of intellectual dishonesty. As anyone is want to do, we'll go from Michael Dempsey to Jesus Christ to Hamilton:

"But when all is said and all is done Jefferson has beliefs. Burr has none."

I Think, Therfore I Am

The pursuit of complex ideas, nuance, complicated problems, and earth-shattering progress and ideas are the most important aspects of what it means to be human. There is a great tweet from Scott Belsky where he quotes Karen Baker, someone who researches imperceptible wavelengths of sound:

"Humans tend to believe that what we don't perceive does not exist. So, we miss a lot."

The idea of the imperceptible world (which Belsky calls mind-blowing) is a fundamental part of artificial intelligence. Something that people have called a "black box" is becoming more philosophical as people can't think of this stuff in generalities, but start to think about it in practicalities. Another great quote on this came from Sam Altman. When asked the question, "After doing AI for so long, what have you learned about humans?", Sam Altman's response was legendary:

"I grew up implicitly thinking that intelligence was this, like really special human thing and kind of somewhat magical. And I now think that it's sort of a fundamental property of matter..."

Until I started writing this, I didn't realize how much this post touched on my religious beliefs, but intelligence is the core of everything I believe. Organized hierarchy, whether religious, political, technological, or otherwise, will always be built upon the foundations of orthodoxy. In other words, commonly held beliefs. In other words, simplified heuristics. In other words, in-group rules.

But progress is often an act of heresy.

The Virtues Of Heresy

In a world increasingly controlled by cowards, it starts to feel heretical to require analytical rigor and question asking, or to display intense optimism in the face of programmatic skepticism. One of the best talks I've heard on this came from Visakan Veerasamy. At the Thesis Festival, he gave a talk called "The Clustering of Citizens Who Can Change The World." Sadly, I don't think the conference captured the whole talk on video. But these citizens who can change the world, he called deviants.

"Most human creativity is spent suppressing human creativity. Deviance is punished by social regulation. That's why we don't have 1000x the greatness that we could have every year."

This same concept of deviants, who are willing to do crazy stuff that spits in the face of tradition or status quo, reminded me of Benjamin Franklin's perspective on heretics as well:

“I think all the heretics I have known have been virtuous men. They have the virtue of fortitude, or they would not venture to own their heresy; and they cannot afford to be deficient in any of the other virtues, as they would give advantage to their many enemies; and they have not, like orthodox sinners, such a number of friends to excuse or justify them.”

The idea of heresy starts fundamentally opposed to hierarchy. The concept of believing something because someone above you, or in charge, or with power tells you to? That doesn't fit into the framework of heretical thinking. I've written before about a book called "The Founders," describing the early culture of PayPal and what made it so unique. This counter-culture of anti-hierarchy was a critical piece:

"This was not a place for the faint of heart. It was a place with really high IQ points and a lot of intense battling over ideas. Building a team that has the capacity to do that strikes me as one of the hardest things to do in business. Because it requires a few things. One, you have to be courageous enough to walk into a room with [one of these people] and tell [them] that [they're] wrong. Which is not easy. The second is you have to actually think very hard about what the right answer is in a given context. Not what you think about the person presenting the idea. You have to think about the idea itself. And then the third thing is you have to do this despite the fact the person talking to you might be a subordinate or three levels above you. It has to be done irrespective of hierarchy because the thing you care about is the idea. We as human beings have the tendency to slouch in the direction of hierarchy absent other things."

The debate of ideas has been largely displaced by the debate of identities. Whether you're conservative or liberal, religious or atheist, capitalist or socialist. We are, in most instances, arguing more about the identity of the person leading the argument, rather than the merits of the idea.

The path to progress more often is built on the value of the ideas themselves, and the execution of those ideas. I think that's why I experience so much cognitive dissonance when it comes to characters like Elon Musk. I can simultaneously think a lot of what he does is gross, while having immense respect for his ideas and execution. But a lot of people can't seem to divorce his character from his contributions.

The Place For Pessimists

In the path to progress, I also think sometimes we lose sight of the balancing forces of uninhibited optimism and unrelenting skepticism. Whenever I consider the valuable role of skeptics and critics, I think about the relationship between Walt Disney and his older brother, Roy O. Disney.

In some ways, Walt Disney was only capable of building the empire he did because his brother's financial and business sense managed to help him to avoid a number of bankruptcies. But in other ways, Roy's pragmatic skepticism was the thing that ultimately ended Walt Disney's vision prematurely. One biography on Walt Disney told this poignant story between Walt and Roy:

"One of the chief reasons [Roy] resisted Walt's pleas and emphasized fiscal accountability was Walt's own management style, which was capricious, idiosyncratic, extravagant, and hopelessly inefficient but what Walt had justified on the basis that creativity, not efficiency, was what counted."

While Walt Disney was in the process of building his most ambitious project ever, the Experimental Prototype Community Of Tomorrow (EPCOT), he passed away. After his death, Roy gave a radio speech seemingly committing to uphold Walt's legacy:

"'There is no way to replace Walt Disney. He was an extraordinary man. Perhaps there will never be another like him.' But, Roy promised, 'We will continue to operate Walt's company in the way that he had established and guided it. All of the plans for the future that Walt had begun will continue to move ahead.'"

But that, unfortunately, isn't what happened.

"A few months after Walt's death Marvin Davis presented the Imagineers' EPCOT plans to Roy. 'Marvin, Walt's dead,' Roy said. And so was EPCOT."

There is always a balance between the inspirational optimists and pragmatic skeptics. On the one hand, I'm heart broken by Roy's lack of vision. When you read about the potential for what EPCOT could have been, it makes sense that people want to believe the vision of Walt Disney is cryogenically frozen. On the other hand, I have so much respect for the dedicated operators that make the visionaries possible. Gwynne Shotwell for Elon Musk. Tim Cook for Steve Jobs. Roy Disney for Walt Disney.

The Pessimists Archive turned me on to a great article written in 1943 in the New York Times entitled "We Need a Fraternity of Pessimists." In it, the author, Arthur Koestler, refers to World War II as a fight against "a total lie in the name of a half-truth."

He talks about how the war was fought against racism, while racism still raged at home in the United States. Or in defense of democracy, while the closest ally of the United States was far from democratic. Half-truths. One key point is that all our horizontal structures—governments, churches, and otherwise—are filled with half-truths:

"The outstanding feature of our days is the collapse of all horizontal structures. That our truths are half-truths is a direct consequence of it. And unless we overcome our reluctance to chew, swallow, and digest the bitter pill, we shall neither be able to see clearly where we stand nor the next steps to take."

Rather than a resounding defense of constant pessimists, the article ends instead with an explanation of short-term vs. long-term perspectives that resonated with my own mindset perfectly:

"Those who are basically optimists can afford to face facts and to be pessimistic in their short-term predictions; only basic pessimists need the dope of the half-truth... What we need is an active fraternity of pessimists (I mean short-term pessimists)... They will watch with open eyes and without sectarian blinkers for the first signs of the new horizontal movement. When it comes, they will assist its birth."

Packy McCormick wrote a similar idea in a different way. Criticism is one important piece of a much longer vision for the optimistic future:

"Optimists move the world forward. There’s something deeply optimistic about entrepreneurship, the idea that it’s possible to create things that have never existed, and find a market for them. Science, too, is optimistic: to run experiments in order to better understand the universe assumes a belief that we can discover more than we already know, and use it to improve the world. Again, that doesn’t mean believing everything and hoping that it will all get better. That’s the opposite of how science works. As Deutsch writes, “there is only one way of making progress: conjecture and criticism.”

Criticism is crucial, but pessimism – “a tendency to see the worst aspect of things or believe that the worst will happen; a lack of hope or confidence in the future” – is actively harmful on both individual and societal levels. If pessimism causes people to stop having kids out of fear, that’s bad. If it makes people give up on trying to improve their environments, that’s bad. If it discourages entrepreneurs from starting companies, or encourages them to play their ambitions safe when they do, that’s bad."

Defaulting To Optimism

When I was at Index, I worked with a woman named Adrianna Ma. She was one of the most eclectic and thoughtful people I've worked with. And we often talked for hours about the ways a venture firm gets built, and how successful it can be. One conversation we had always stuck with me where she talked about balance:

"Every venture firm is a balance. Every idea brings out the skeptical pessimists against the idea, and the enthusiastic optimists for that idea. Every potential investment will have some of each. But the skeptics can't always win, or we'll never take big swings."

In a recent piece, I called myself an optimism maximalist. However, a lot of my writing is criticizing the way people think, the way they make decisions, the incentives they allow to influence them. So I can come across as increasingly pessimistic.

But instead, I agree with Arthur Koestler. I'm so eagerly tied to the potential for the future and the optimistic picture of what the world can be, that I'm willing to accept the short-term problems. I’m willing to swallow the bitter pill. I'm not trying to dull my senses to the intellectual negativity or complacency around us. I'm more interested in understanding the problems that plague us, and then helping to paint the picture of what the future could look like.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Thanks for this salve for the innovators soul.

I loved your reference to Accel's Prepared Mind principle, so I dug into to one of Rich Wong's interviews. Apparently Louis Pasteur brought this up in a lecture in France in 1854 - "In the fields of observation, chance favors only the prepared mind".

Great example of how wisdom endures