The Existential Dread of Cognitive Dissonance

“So much of our lives is meaningless, a self-canceling vacillation and futility."

This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

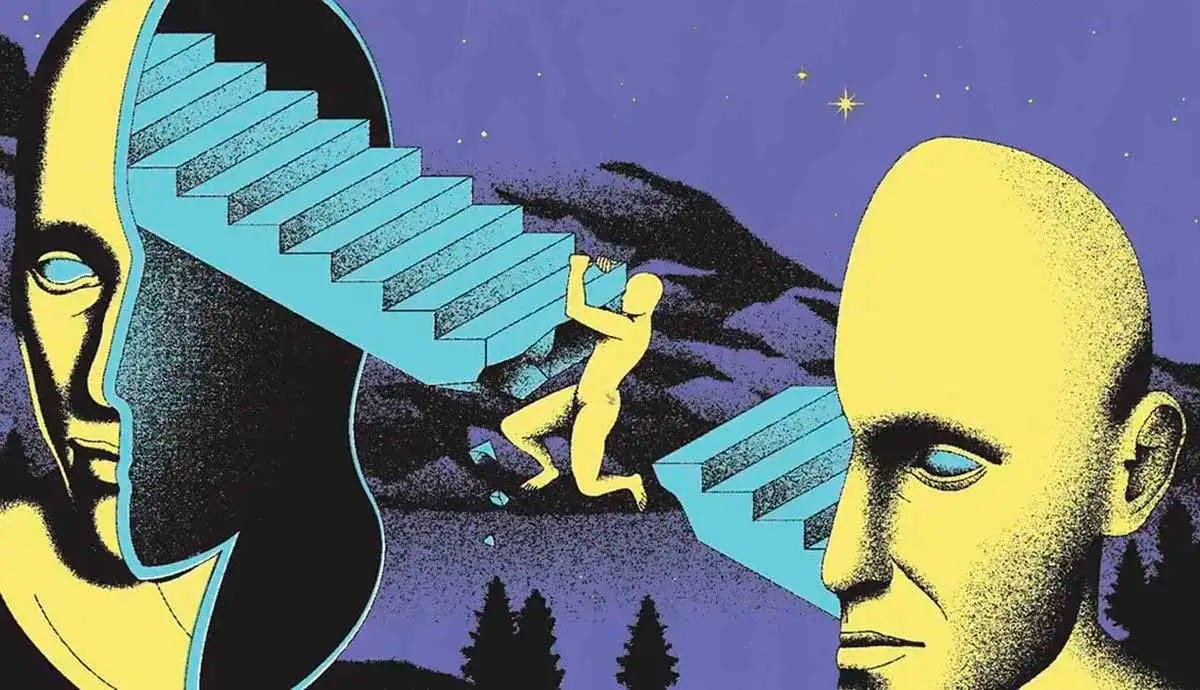

When I was in 10th grade, I had to do a writing assignment. Over the course of the year we were supposed to read two books by the same author, and identify common themes and style choices that say something about the author.

I assumed everyone would blow this off until the last second, which is what I proceeded to do. Days turned to weeks, and weeks turned to months. After a while, I started hearing from my fellow students about the books they had finished.

"Finished?" I hadn't even picked an author, let alone finished anything. In a moment of panic, I went to a library and asked what authors they thought might have the shortest book. That's when I was introduced to every procrastinator's favorite word: "novella."

Still constituting a "book," but dramatically shorter. Perfect! The librarian led me to a few books she thought would be just the right fit for me. The books? Notes From Underground, and The Gambler by Fyodor Dostoevsky. Both shorter than 200 pages, exactly what I was looking for.

I don't remember what I got on the assignment. I actually still have the paper I wrote, and reading it makes me think I probably didn't get a great grade. But that chance encounter with Dostoevsky was my introduction to existentialism, and Russian literature more broadly. I discovered books like Crime and Punishment and Anna Karenina that would become some of my favorite books.

When I re-read that paper that I wrote thinking about the existential place I often find myself, I was struck by this quote from Will Durant:

“So much of our lives is meaningless, a self-canceling vacillation and futility. We strive with the chaos about and within, but we should believe all the while that there is something vital and significant in us, could we but decipher our own souls.”

Deciphering Our Own Souls

So what got me into such an existential quandary that led me back to the Russian existentialists of my youth? My wife and I had dinner with some friends this past week. Neither of them work in tech, or have much exposure to venture capital. So they were asking casual questions about it.

One topic progressed to another, and we were deep into the weeds on the types of excess and hubris that exist in venture capital and building technology companies more broadly. In my mind, I kept coming back to this tweet from Delian.

The final piece of the puzzle that pushed me into a cognitive tailspin was a text conversation I had with one of my VC friends a few weeks ago after IRL shut down. My friend and I had talked before about the excess of companies that have gotten built and ultimately destroyed wealth, often while still leaving the bad actors enriched.

Then my friend perfectly captured the things I'd been feeling (edited for clarity and anonymity):

"It just sucks. Our industry should be more responsible. Obviously it’s first on the founders themselves, but let me hold a tiny bit of cynicism for the VCs. So many examples in our industry these last few years (SPACs, crypto) where you ‘did your job’ by making money but shit the bed ethically.

It helps to thrive on the good stuff and good people, living your values, being a truth teller (including punching up), and making sure you're using your own scorecard, not someone else's. Yes, there are performance benchmarks that wrap us (as VCs) into competitive brackets, but it's not a winner-take-all world, and you can make it a single-player game and still win.

Getting bigger forces you to say yes to things you might not otherwise say yes to. I'm more interested, instead, in punching our industry in the face by helping as many VCs as possible succeed, building competitors to the most mediocre of VCs so that they can get eaten faster."

I realized that a lot of this same frustration is why I wanted to join a firm like Contrary. I wanted to do things differently in an attempt to do things better. Conveniently, as I was brewing all of this in my mind, Paul Graham published a great essay today to go along with it called "How To Do Great Work."

In it, he set out to articulate a recipe for answering this question: "If you collected lists of techniques for doing great work in a lot of different fields, what would the intersection look like?" Here was a snapshot of it:

“Four steps: choose a field, learn enough to get to the frontier, notice gaps, explore promising ones. This is how practically everyone who's done great work has done it, from painters to physicists."

The rest of the essay is exceptional, but this key idea of noticing gaps and exploring the promising ones resonated with me. My writing is so often about the art and science of investing itself, rather than just company building, because its a reflection of my own exploration into my chosen field.

My main piece that kicked off my process for exploring changes in venture capital and then writing about them was in "The Unbundling of Venture Capital." In it, I used a quote from Don Valentine that is very similar to this idea from Paul Graham:

"One of our theories is to seek out opportunities where there's a major change. Major dislocation in the way things are. Wherever there's turmoil, there's indecision. And wherever there's indecision, there's opportunity. So we look for the confusion when the big companies are confused. When the other venture groups are confused. That's the time to start companies."

That's what I want to be doing. Identifying the gaps in how companies get funded and built, and then exploring the most promising gaps that could lead to fundamental changes.

Choosing Good Quests

Finally, I was led to another piece I wrote about last year. Trae Stephens and Markie Wagner wrote a phenomenal piece called "Choosing Good Quests. Read the whole piece.

As it relates to my feelings about venture capital, it comes down to what we're incentivized to build. I often find myself articulating this by using Hollywood as an analogy. The "business of blockbusters" has pushed movie studios to focus on spin-offs, sequels, and reboots. While this can lead to exciting movies, it rarely leads to unique stories.

I'm reminded of a story where Steven Spielberg complained that he had almost been forced to release his film, Lincoln, as a mini-series instead of a full feature film because he couldn't get anyone to fund it! A movie made by Steven Spielberg, starring Daniel Day-Lewis! But the studio model had pushed those unique stories into the periphery in favor of massive blockbuster potential.

Venture capital is facing a similar problem. The economic model pushes for bigger and bigger outcomes, that require more and more capital. This leads to larger funds, larger rounds, more cash burn, and more exorbitant ambitions. And don’t get me wrong, I don’t have any problems with ambition! I want to see the full unlock of human potential. Automation, robotics, diseases cured, and space traversed. But the ambitions are, so often, luxury dog houses dressed up as solutions to the housing crisis.

The world of change-making would be much better off if venture capitalists would leave the financial engineering to the "growth investors" and focus, instead, on being the idealistic enablers that they were meant to be. Nerdy fans of science fiction, human progress, and Utopian idealism. The world, instead, moves further and further from manifesting the imaginable, descending deeper into a culture war of frustration and fear.

There is something vital and significant within each of us, if only we're willing to decipher our own souls. And I intend to do all the deciphering I can.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Man, I love your way of thinking! I agree that too many VCs are chasing after meaningless things just to fulfill some vanity metrics. I really hope that firms like Contrary succeed in the long term, to show the market that there are alternatives to the current paradigm.

I've been in the startup space since 2016 and this is the best summary that encapsulates why startups work, but also why the system fails them and itself. It's a vicious cycle.

The quote around finding the gap that also leads to big change is a great one. And I really like Contrary's focus on the individual

I'm gonna shoot my shot here since this write up resonated with me so much, but I'm currently targeting the idea to first customer stage of founders, where there is a clear gap on how the industry guides these individuals. Letting 98% if them down, since the incubator acceptance rate is on avg 2%. We flip the industry standard of passive learning through content for the 98%, and are using a question based approach. Think TurboTax but for startups.

In the end, by collecting the responses to the TurboTax like questions, we are creating a dataset that has 0 survivor-ship bias, insight into the founders and their thought process, and it allows us to create personalized AI and tools for them. This data drives are higher vision of providing tools and streamlining the whole startup space since all of it is based on this startup data... Granted very manually right now.

Startup is Dium (www.startdium.com) if this does pique your interest and we have 64 users for our MVP