This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

There are a few things that stick in my mind so much it feels like they're a fundamental part of my personal source code. Movies, songs, sayings, quotes, commercials for Campbell's chicken noodle soup. One such entry in my repo is the 2006 movie Night at the Museum. But the part of the movie that made the cut might surprise you. I think all the time about the first 7 minutes of the movie.

At the beginning, Larry (the main character) goes to pick up his son from his ex-wife's house, and chats with her goober fiancé, Don. Don is a bond trader who wears a beeper, cell phone, and Blackberry attached to his belt like a Wall Street Batman (2006 was a simpler time). After Larry takes his son, Nicky, to his hockey game, they're walking through Central Park.

His Dad is telling him what a good job he did, and how the NHL might be a serious possibility.

Nicky: I don't really wanna be a hockey player anymore.

Larry: All right. What do you wanna be?

Nicky: A bond trader.

Larry: A bond trader?

Nicky: Yeah it's what Don does. He took me to his office last week.

Larry: But you love hockey.

Nicky: Yeah, but bond trading is my fallback.

Larry is an entrepreneur, with dozens of failed business ideas like virtual reality golf courses or the snapper (the clapper, but with snaps). A lot of kids idolize their Dads, regardless of professional outcomes. But Nicky, who is ten years old, has latched onto his soon-to-be stepdad's career as a bond trader! Why?

Kids absorb what they get exposed to. Especially before kids get into their teenage years, ego and paranoia haven't set in yet, and so they are able to be uninhibited sponges soaking up everything they see, hear, and experience.

My perspective: the biggest disservice we do to our kids comes from two key forces:

(1) What your kids are exposed to is the path of least resistance

Life is too noisy to leave you alone. If parents don't help their kids get exposure to a broad variety of experiences, then life will put something in front of them. And the loudest, flashiest thing is unlikely to be the best experiences life has to offer.

(2) As we focus more on outcomes than experiences, we leave our kids with anxiety, rather than resilience

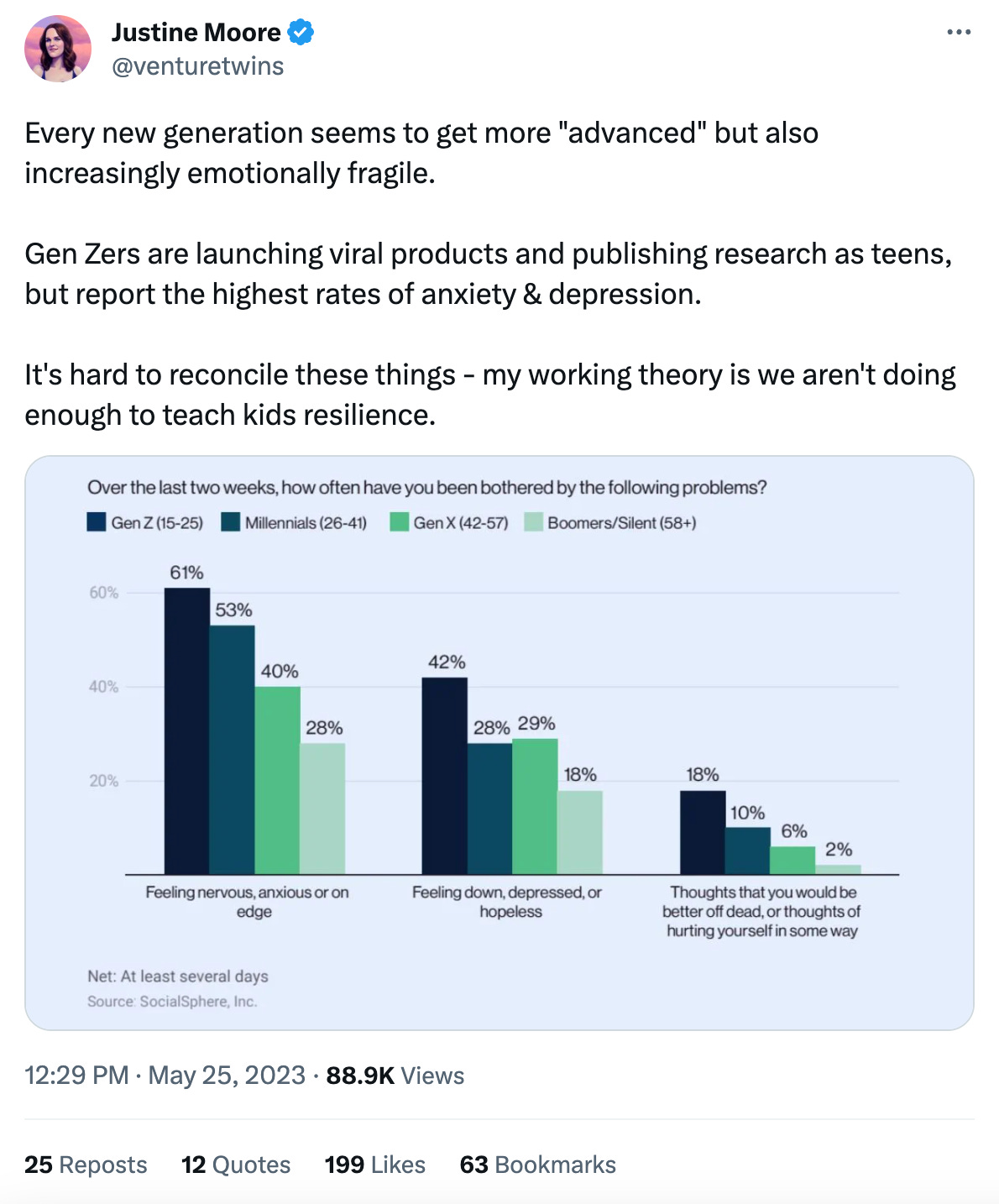

Grades. Colleges. Medals. Awards. Kids lives revolve around outcomes. Parents feel good about outcomes because they're measurable and easily compared to the outcomes of other kids. And to kids credit, they're stepping up. They've risen to the occasion, and are often producing the outcomes their parents pushed them towards. But at what cost? "Gen Zers are launching viral products and publishing research as teens, but report the highest rates of anxiety & depression."

Justine has a good follow up point to make here:

"People blame social media/the Internet, but I think parenting plays a big role. Many parents want to make life easier for their kids + give them a leg up, and go out of their way to remove obstacles. This might be beneficial in the short-term, but has long-term consequences."

If your focus, as a parent, is on your children's outcomes, then what are obstacles but simply things to be removed to get to the actually important stuff? But what that leaves you with is a well-credentialed kid riddled with anxiety about the next outcome.

And that has implications for the startup ecosystem as a whole. The cultural vibes of startups has changed dramatically in the last few years. How we parent our kids impacts the types of innovation that will happen going forward.

The Path of Least Resistance

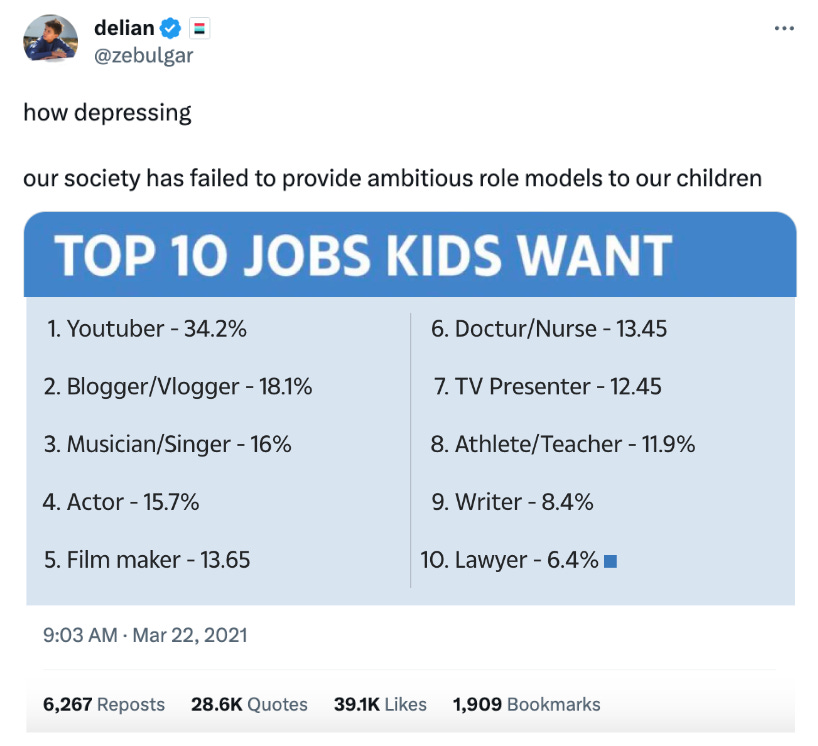

The aspirations of the rising generation often revolve around what they spend so much of their time doing: being online. The numbers Delian is referencing above is based on a 2017 survey of 1K kids. Here, I think you have two forces at work: (1) outcome-based pressure (e.g. doctors, lawyers), and (2) no pressure at all (what I see is what I want to do).

Being a Youtuber is the "bond trader" of most young people's lives. It’s what they’ve been exposed to. What they're exposed to is what they absorb and shapes who they are, and how they think. Now, if I was grouchier than I am, I might just write this off as "we don't do a good enough job of inspiring kids to be something useful, rather than Youtubers." But I frame it differently. We don't do a good job of shaping kids expectations of what they can accomplish.

Whatever You Are, Be A Good One

Mike Birbiglia is one of my favorite comedians, and I have to credit him for telling a joke that brought this phrase to my attention. So even if Abe didn't say it, I still like the saying:

"I stayed at a hotel last week in Washington, D.C. It was the Abraham Lincoln Suites, and they have these Abraham Lincoln quotes everywhere. And one of them was like, 'Whatever you are, be a good one.' I just don't feel like he should get credit for generalities like that. Like, 'How Are Ya?' -- Abraham Lincoln."

When you hear cliché parents in cliché movies say cliché things like "you'll never make it as a rock star!" I'm reminded of this quote that my friend Rex Woodbury showed me from a 2005 interview with Barry Diller:

“There is not that much talent in the world. There are very few people in very few closets in very few rooms that are really talented and can’t get out. People with talent and expertise at making entertainment products are not going to be displaced by 1,800 people coming up with their videos that they think are going to have an appeal.”

But the reality is that there are, in fact, a LOT of talented people in the world. And the internet has unlocked them.

When it comes to Youtubers, think about Mr. Beast. He has dozens of businesses, a $500M net worth, turned down a $1B acquisition offer. I love seeing TikToks of him on podcasts talking about the maniacal focus he has on his craft. He's posted something like one video every 10 days on average for a decade.

He's not just a weirdo posting complainey videos in his Mom's basement. He started as a little bit of a weirdo posting videos of himself pseudo-rapping commentary on Call of Duty releases. But his maniacal focus, distribution, and capabilities are as good as any tech founder! He's built what Alex Lieberman calls the combination of "a modern-day holding company (think Pepsi/Unilever) with a media behemoth. It's like if HBO bought Hasbro or ESPN merged with FanDuel."

So to some extent, I'll disagree with Delian. It's not that being a Youtuber is a failed aspiration. Being a Youtuber has enabled Mr. Beast to give away millions of dollars, offer hundreds of people eye surgery, and so much more. Instead, it's about recognizing that you can set out to be anything, but you should strive to do it well.

So does this contradict what I said about emphasizing experiences over outcomes? Let's unpack that.

Experiences Over Outcomes

I come back to this quote from Alan Rickman all the time, where he’s giving advice to aspiring young actors:

"Forget about acting. Whatever you do as an actor is cumulative. Go to art galleries, listen to music, know what's happening on the news, in the world, and form your opinions, develop your taste and judgement. So that when a quality piece of writing is put in front of you your imagination, which you've nurtured, has something to bounce off of."

Is he saying "don't be an actor"? No. He's not invalidating the outcome entirely. Instead, he's emphasizing the role that experience plays in shaping who you are when you finally arrive at that outcome.

Every person is capable of so much more than they typically accomplish. And I'm not talking about unreasonable expectations, grind culture, or unhealthy comparisons. I'm saying that within every person there is more capacity than they typically take advantage of. Enabling kids to do hard things, and learn along the way, is the way to unlock that capability.

The Capabilities of Kids

One of my "quake books" is the biography of John Quincy Adams, which is a pretty weird one to choose. But I love the stories of both John Adams and his son, John Quincy Adams. They were for sure flawed people, but they had exceptional characteristics that I've learned from. From journaling, to education, and more.

One story that I think about all the time comes from a time when John Quincy Adams was serving as the U.S. Ambassador to Russia in 1809. His 8-year old son, George, was with him and I think about this passage from the biography by James Traub:

"Adams spent the spring and early summer practicing the law in his desultory way, reading, and seeing to George's education, as his parents had seen to his. Every morning before eight he and George took turns reading to each other four chapters of the Bible, and then father and son talked about the meaning of the passages. He showed George the countries of the world on a map. He took George to a performance of Hamlet."

Again, John Quincy Adams had tons of flaws. After he served as President, he forced his family (including his grandkids, to call him "the President.") In the families of both him and his Dad, there were suicides, bankruptcies, and alcoholics. These are not blank role models for parenting. But just picturing the education of an 8-year old boy being so one-on-one, its nearly unheard of in education and parenting today.

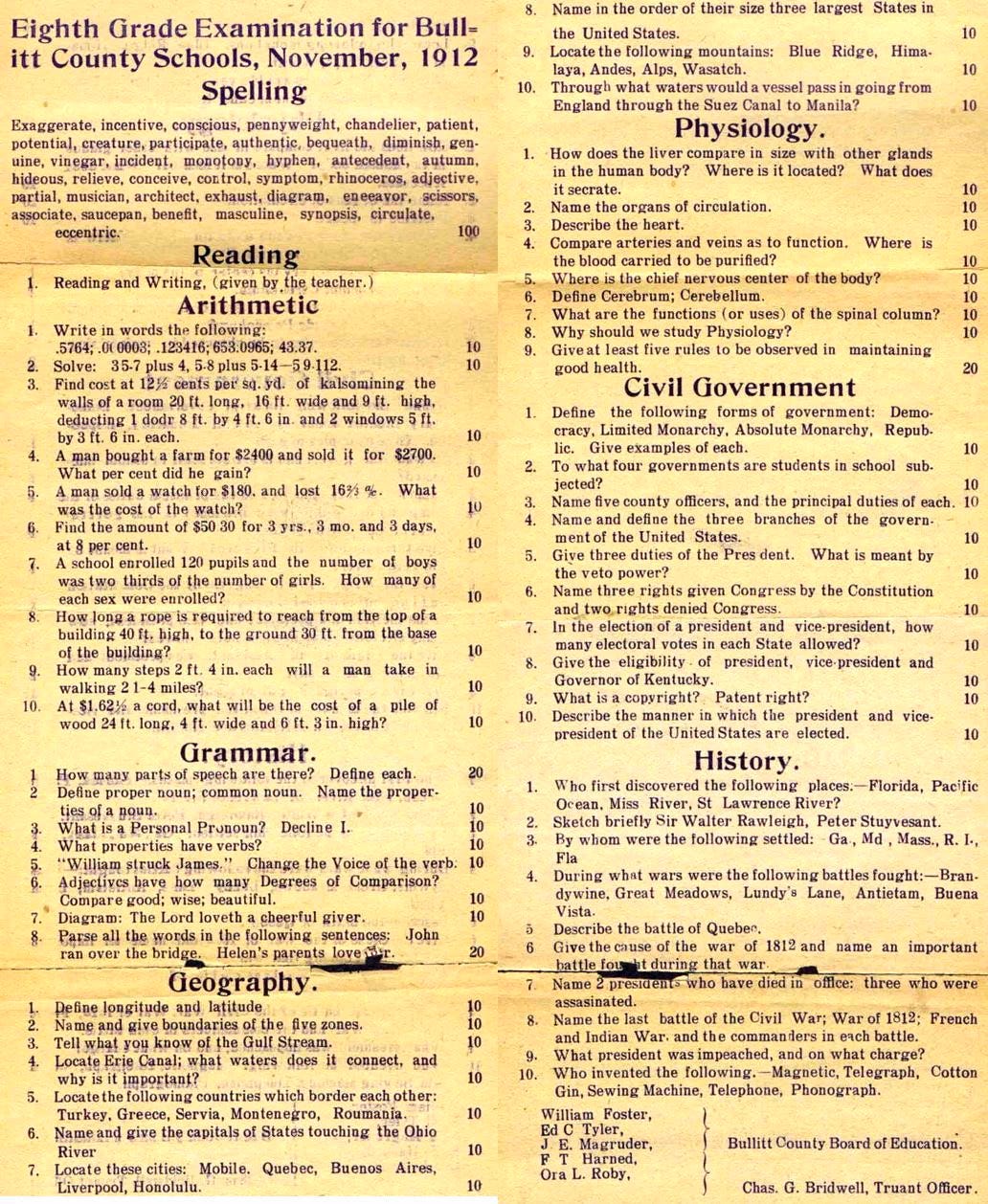

That also reminds me of this exam from 1912 I saw on Twitter that was for 8th graders!

To some extent, we've lost sight of what young people are capable of. The average age of Hollywood stars goes up by 0.75 years every year. CEOs at the age they were hired has gone from ~45 in 2005 to ~68 in 2019.

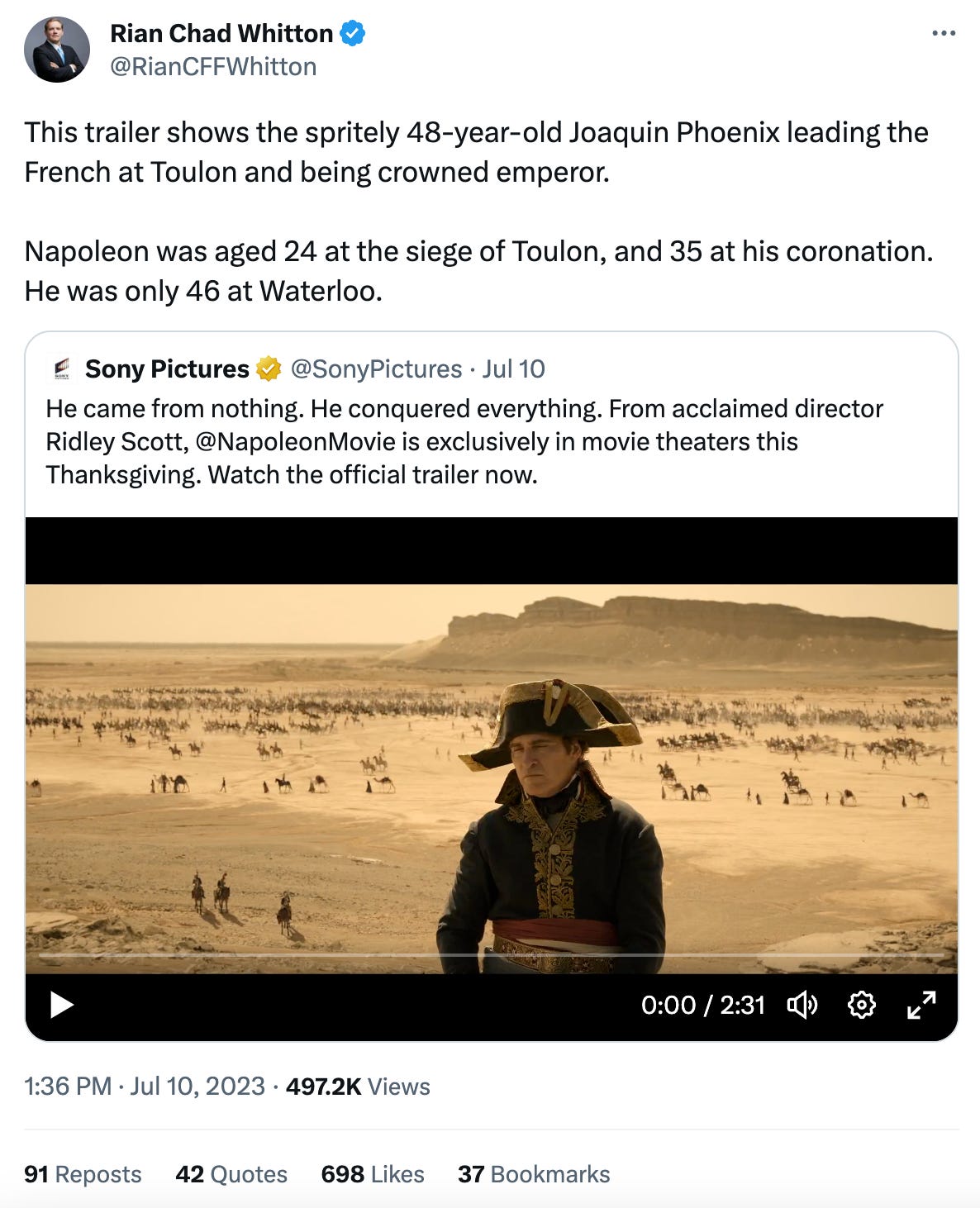

Liberty had a great post about Napoleon and young leaders back in July when a trailer for a new Napoleon movie came out. He credit Rian Whitton for making this point about Napoleon's age:

In Liberty's post he asks the question, "Is this because audiences couldn’t suspend disbelief if Napoleon was played by an actor of the actual age of Napoleon during these events?" Are we so far removed from witnessing the capabilities of young people that its outside the realm of possibility in our imagination?

I think about this every time I tell my kids they can't do something, or I think they need my help doing something. There is so much that parents have been programmed to see as unnecessary obstacles that its their job to remove. When in reality, we need a lot of reprogramming ourselves to see that kids are capable of much more than we give them credit for. The more we can reprogram our expectations, the more our kids are enabled to do for themselves.

All of this makes me think about Derek Sivers who, after selling his company, is effectively living a dream of a life just writing and raising his children. From his book, "Hell Yeah or No":

"Since my son was born five years ago, I’ve spent at least thirty hours a week with him, just one-on-one, giving him my full attention. But I’ve never written about parenting before because it’s a touchy subject — too easily misunderstood. So why am I writing about it today? Because I realized that the parenting things I do for him are also for myself. And that’s an idea worth sharing."

The Silicon Valley Vibe Shift

So what does all of this have to do with investing and company building? You've let me ramble about the thoughts going through my parenting head, now I'll bring it home. In 2007, when Facebook was just 3 years old, Mark Zuckerberg spoke to a group of YC founders:

"Young people are just smarter. Why are most chess masters under 30? I don't know...Young people just have simpler lives. We may not own a car. We may not have family."

In the book The Power Law, it goes deeper into this early Silicon Valley mentality that Paul Graham was a big proponent of. The emergence of startups as a viable career path for younger people rode in tandem with the rise of the internet. Paul Graham wrote in June 2013:

"When I graduated from college in 1986, there were essentially two options: get a job or go to grad school. Now there's a third: start your own company. That's a big change... That kind of change, from 2 paths to 3, is the sort of big social shift that only happens once every few generations. I think we're still at the beginning of this one. It's hard to predict how big a deal it will be. As big a deal as the Industrial Revolution? Maybe. Probably not. But it will be a big enough deal that it takes almost everyone by surprise, because those big social shifts always do."

While Silicon Valley as an idea has always been one for rebels and outcasts, it hasn't necessarily been exclusively for young people. The quintessential birth story of Silicon Valley is the Traitorous Eight who left Shockley to found Fairchild Semiconductor in 1957. At the time, the average age across all eight was ~32 years old. Not exactly the 19 or 20-year old archetypes we saw with the founders of Microsoft, Apple, or Facebook.

I do, in fact, recognize the discomfort of having to acknowledge in writing that people my own age now were not, in fact, young.

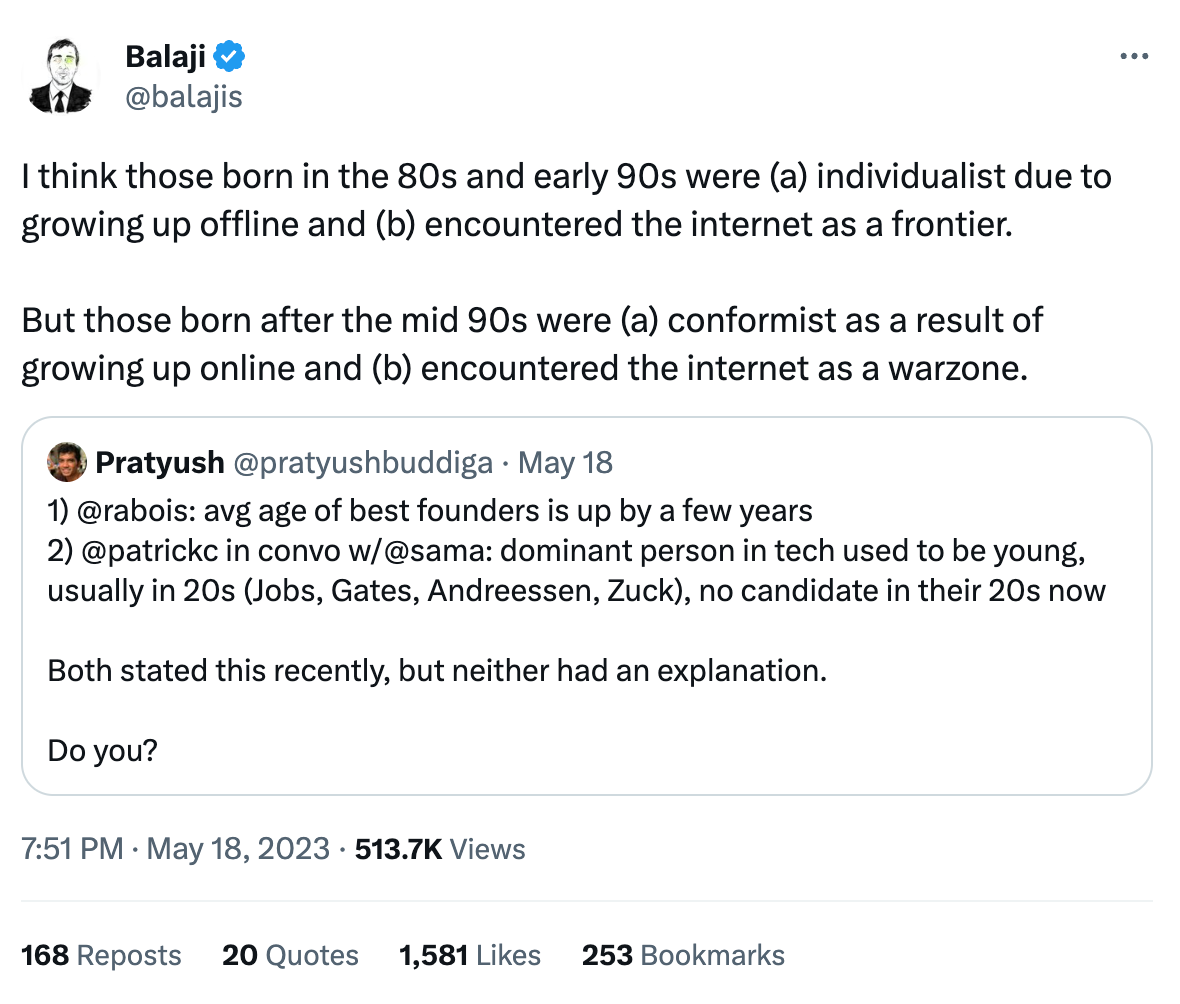

Balaji Srinivasan has a great thread that I think brings this point home. Over the course of a week or so in May, Keith Rabois, Patrick Collison, and Sam Altman all made the observation that the dominant players in tech are no longer 20-year olds.

I still remember the day my family got dial-up internet. I remember the screech of hope as my computer logged online. I remember the first websites I went to. I remember learning to write HTML so I could customize my MySpace page. Describing the internet as a frontier to people who logged on in the 90s and early 2000s is soulfully accurate.

Since then, the internet has increasingly devolved into tribalism. Balaji makes the point that the founder, creators, and influencers who are thriving in the current internet age are "tribal leaders." Call them taste makers, aggregators, curators, whatever you want.

It can sometimes be easy to think of "Silicon Valley" as established, tried and true. We forget how young all of this still is. Gordon Moore, one of the traitorous eight, and the source of Moore's Law only died in March of this year! Fairchild was founded ~60 years ago, personal computing is maybe 50 years old, the internet is only ~30, mobile is like 16 years old. All of this is so new, so to think that its not going to change dramatically is naive.

The question is HOW Silicon Valley will change? And what role do young people have in building the next generation of great innovation and technology?

Venkatesh Rao has a great piece called "Silicon Valley Generation Shift" that I'm going to quote from extensively because his observations so well captured my perspective on what is happening in terms of where the sharpest people, both young and old, are congregating. In the piece, he talks about this concept of Silicon Valley in time:

"People often talk about Silicon Valley in space, and speculate about where the next Silicon Valley might be, but they rarely talk about Silicon Valley in time, and things like inter-generational dynamics. Cohorts in Silicon Valley are surprisingly separated. The hungry young people trying to make it and the established older people who have already made it don’t usually mix much, outside of pitch meetings and conferences. They inhabit relatively separate cultural scenes. The streams don’t cross."

He goes on to explain how the next shift is enabling a decoupling from a specific geography:

"The next generation of technology is notable in that a big chunk of it is not in Silicon Valley. It is notable that my travel in relation to my latest work in the crypto and climate/energy ecosystems has had me heading to very different places — Bogota, Denver, Sacramento.

The most interesting thing about the younger set cycling into the region this time around is the people who are not there. The talent that is choosing to operate from elsewhere. The region is no longer the obvious smartest place to move to. During the last two busts, in 2000 and 2008, things slowed down, but Silicon Valley remained the obvious default destination. This time, it’s different. Thanks in part to videoconferencing finally being basically free and good."

Now, before the SF loyalists freak out, I don't even think this is just a knock on SF as a place to live. Much more broadly, the new vibes are just more spread out. Even people who are "based" in the Bay Area are still often spending a lot of time elsewhere. Industries like defense or carbon capture are in LA and Denver more than they're in SF.

Then, Venkatash turns to AI as a big catalyst for a lot of this cultural shift:

"Finally, the curious culture that is emerging around the emerging AI industry. Even though everybody in tech is talking incessantly about AI, they mostly talk like spectators rather than players. Even though several of the major institutions of AI are in the region (Google, Facebook, Stanford, OpenAI, Tesla) it does not feel like Silicon Valley spiritually “owns” AI the way it did Web 2.0."

Even Microsoft, who between their acquisition of GitHub and their massive partnership with OpenAI, is seemingly the biggest player in the current AI boom, is based in Seattle.

Balaji makes a similar point in his thread about the cultural undertones of AI as a movement of people, and processes.

General social networks will give way to micro social networks. Interests and skill sets will become the most important identities. That feeling of many of the people talking about AI talking as "spectators rather than players," that is a reflection of the forming of a new out-group.

AI, nuclear fusion, high speed air and rail transportation, robotics, genetic food alternatives, direct carbon capture, and several others—those are the new frontiers. And they have a lot more barriers to entry than my dial-up internet.

Does that mean all tech companies need to shift to fit those frontiers? No. Lots of good companies can be built in all sorts of ways. In and out of tech. But I do think companies building a wide variety of models, whether its run-of-the-mill SaaS, reinventions of old financial processes into fintech products, or even a better model for building laundromats and HVAC repair, they all need to be aware of the different games that are being played.

It's dumb to think a model that can fund nuclear fusion is automatically also the best fit for a personal finance app. So we should revisit that sometime.

But to bring it back to my core reflection on the rising generation. I want my kids to be aware of the frontiers. And I want to help them to be capable of overcoming the barriers to entry, and engaging with these challenging and compelling frontiers that exist, to solve hard problems.

The last thing I want is to find myself with a 30-year old son, in the midst of a nuclear fusion renaissance, and for my son to say "Dad, weren't you paying attention when this revolution began? Why didn't I know about it when I was a kid?"

Let's Ask Dax

To wrap it up, and keep me grounded, I took the topic to my kids. My oldest son's name is Dax. He'll be 7 years old in a few months. This morning, he came down to say good morning and I asked him, "What do you want to be when you grow up?" His response?

"A Ninja."

Then he paused for a bit.

"How do I get good at karate?"

I'm proud of him. We'll see how his ninja aspirations play out. But even more than that, I'm proud that his first thought is to ask the question "how" do I get what I want? That's a good first step towards appreciating the journey as much as the destination.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

So a great article.

You lost me at Balaji