This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I'm not a sports guy. We are not a sports family. Growing up, my parents loved sports, and watched them a lot. But it wasn't my thing. That has reflected in my children. A few years ago when my oldest son tried soccer, we spent most of our time trying to get him to stop going up to the ref every few minutes asking, "hey, how much longer do we have to do this?"

So my sports stories and analogies will almost never come from real life. They'll either come from true classics, like Remember The Titans, or from comedians relaying sports stories much more entertainingly than anything I've ever seen on ESPN. One such comedian is Nate Bargatze.

He tells this story of playing baseball when he was younger. He's up at bat, and gets walked. When he gets to first base the catcher is still holding the ball, as if daring him to run. So he does. The catcher throws to second, but overthrows, so Nate keeps going, making it past third. Everyone's losing their minds. "This is about to be an inside the park home run off a walk. This is the biggest thing to happen in sports."

Finally, he slides into home plate. The umpire looks down at him and says, "it was only ball three." (For those of you that need some context, in baseball you actually need four balls to get walked. I had to google it to be sure.) So he has to stand up, pick up his bat right where he left it, and he's already got two strikes. The next pitch? Immediately strikes him out. The umpire says, "Okay, now you can go."

I couldn't care less about baseball, but I couldn't love that story more. The interesting turns our lives take, huh? At the end, Nate Bargatze has this great line:

"I did learn something though that day. What I did learn was that if you're confident, you can get away with quite a bit, you know? Cause why didn't anyone stop me? No one stopped me. They knew I wasn't supposed to be going, but I was so confident about it. [The kid holding the ball] was like 'is he supposed to be doing this?' And then I run to second, and it's like 'well no one is that much of an idiot. I guess I wasn't paying attention.'"

Life is, contrary to what every drunk little league dad is convinced of, not like sports. Sports have specific rules. As confident as you are, you might be able to convince people for a few seconds as confusion still reigns. But when the dust settles? It was ball three. And then you're out. The rules come for everyone (unless... you know, like roids I guess.)

In life, we play games that are riddled with a lack of rules. And, to Nate's point, confidence can get you quite far. Because so many of the games we're playing are pretty stupid games.

The Games We Play

In April 2021, Ev Randle, who was then at Founders Fund, and has since jumped to become a partner at Kleiner, wrote a piece called "Playing Different Games: Why Tiger Is Eating Your Lunch (& Your Deals)." This was the peak of Tiger's dominance in the zirpy days of fast-moving, high-priced rounds that never seemed to end. A company would be preempted 3 times in 9 months.

Now, no disrespect to Ev and his writing because (1) I think he is a sharp guy, and (2) I still think his piece is an exceptional exploration of changing business models within venture that you can learn a lot from. But there are some things that went very wrong and, with the benefit of hindsight, can be instructional.

In the piece, Ev lays this groundwork for the discussion (and remember this is in 2021, a year that Tiger would go on to do 356 investments(!)):

"Ask 10 VCs for their thoughts on Tiger et al and most of them will react with a mix of dismissiveness and disgust. They’ll say that crossovers are drastically overpricing rounds, not doing enough diligence on their investments, or are in some other way breaking the spoken & unspoken “rules” of venture. By breaking many long-held but outdated rules & norms of venture/growth investing, Tiger has developed a flywheel that enables them to offer a better/faster/cheaper product to founders while generating more $ gains than their competitors."

There are those rules again. It felt like Tiger could "break the rules" in 2021 because rules don't really exist in the same way they do in baseball. Ev's piece outlines how Tiger is playing a different game by pre-empting rounds, moving quickly through diligence to term sheet, paying very high prices, and taking a lightweight approach supporting companies.

Again, with the benefit of hindsight we know that this leads to a basket of overvalued positions, a huge drawdown from your hedge fund, a fire sale via an investment bank, and disgruntled employees making up salacious memos about your firm. They weren't just playing different games, they were playing stupider games.

In terms of rules, I actually agree there are very few "rules" in real life, but there are powerful forces. Forces that can be difficult to escape from or avoid. As powerful as gravity, but as made up as capitalism. And some of these forces shape the way that companies are made, and capital is deployed.

Company Building Games

I'll start first with an example that I talk about quite a bit when talking about the AI hype happening right now. After the incredible whiplash of 2022 where venture investing dropped by ~60% from a peak of $214B in Q4 '21 to $79B in Q2 '23, I've tried very hard to wrap my head around how the AI hype can be just as fervent as 2021. Didn't we learn anything?

The important distinction is that within the AI landscape there are three distinct "games" being played, and failing to understand that those games are, in fact, different games is, in and of itself, a stupid game to play.

These buckets are completely made up by me, and I'm sure much smarter people would disagree entirely. But this is how I've thought about the different things playing out in AI:

Corporate Fiefdoms: Companies that have aligned themselves to large corporate interests, often driven by their cloud computing businesses.

Tools of the Trade: Companies that leverage AI but spike in other areas (e.g. Replit is a code environment that leverages AI), or a tool that powers the overall ecosystem.

Wrappers & Vaporware: Things that are almost entirely indefensible, often with episodic revenue, and are primarily powered by something from one of the first two buckets.

Here's where the danger of stupider games comes into play. So many companies are looking at OpenAI and saying "yup, that's the game I'm playing." Your golf app that "leverages AI" to suggest personalized swing recommendations is definitively NOT playing the same game as OpenAI.

Recently, Sam Altman said he felt bad about all the advice he gave when he was running YC because they ignored 90%+ of if in building OpenAI. But Garry Tan, the current president of YC, made this point about different games:

Don't get me wrong. OpenAI is an exceptional company. They've positioned themselves incredibly well in an AI boom, and that's what has allowed them to supposedly reach a $1B revenue run rate in just two years. But building a company like OpenAI is a dramatically different game than building Stripe, for example.

So companies who not only base their operations on OpenAI, but also their valuation expectations, will end up finding themselves playing stupider games.

I wrote a piece over a year ago called "What's In a Valuation?" where I tried to unpack the "valuation stick" that founders pick up when they decide to raise at a massive valuation. When you pick up one end of the valuation stick, you end up picking up the other end that is fraught with significant expectations of outcome.

Every company wants to have the biggest aspirations. And often, those hungry ambitions are what makes a great founder. But anchoring your expectations in a different game will almost always lead to dissatisfaction. Michael Jordan was the greatest basketball player of all time, but a middling baseball player. The games we play should shape our expectations about our potential outcomes.

Granted, it isn't just founders that are shaping these expected (and often dramatically inflated) outcomes. The business model of venture capital has done a lot to force founders to focus on very different games because investors need very different outcomes to make their own math work.

Capital Allocation Games

My primary subject in my writing is about the business model of venture capital:

But the framework of different games is the most important distinction that I can make when it comes to understanding that business model. Was Tiger playing a stupider game in 2021? Yes. But that wasn't a one-off blip. That was an over-extended version of a business model that is alive and well in venture capital.

Venture capital, as an industry identifier, is not an effective catch-all. Different firms are playing (at least) one of three games. And failing to understand that those games are, in fact, different games is, in and of itself, a stupid game to play.

There are a myriad of ways you could segment any group of firms, and most firms have lots of different defining characteristics. None of these are necessarily bad. But understanding their business models are critical.

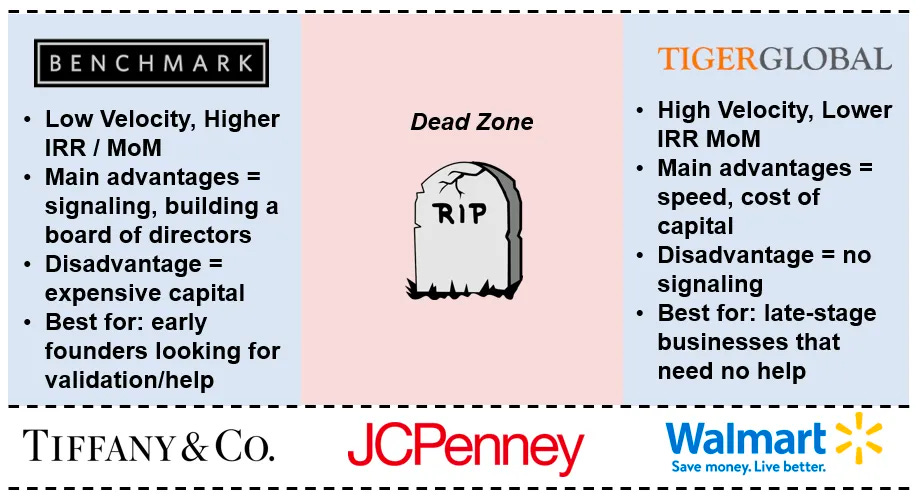

In Ev's piece on Tiger, he has a similar dichotomy with a much starker takeaway:

Understanding the different approaches and models of different firms are instructive. Ev’s piece is still informative, even if he got his praise of Tiger wrong, he got his breakdown of the dichotomy in VC business models very right.

Even outside of AI, there have been a few rounds done this year during an otherwise bone dry funding environment that have been reminiscent of 2021.

Some of those rounds get done by firms that are desperate. They're clinging on to relevance, and in a desperate attempt to remain in the conversation they're winning deals by putting up the biggest numbers. Those firms aren't long for this world (though time, to a venture fund, is relative, and the death of any venture fund comes slowly.)

But another swath of these non-AI zirpy investments have come from specific firms. Firms that I call "capital agglomerators." These are firms that are truly playing out the vision of becoming the Blackstone of Innovation. The goal is just to raise as much capital as humanly possible. It is unlikely that any of these kinds of firms would do what Founders Fund did a few months ago in cutting its latest venture fund in half.

People will ask, "how, in 2023, can you do an investment with a few million of ARR for a $1B valuation?" Because capital agglomerators, by attracting massive LPs who are giving them $250M a pop, are playing a dramatically different game. No LP expects 10x returns on $250M of capital. They're more than happy with 2-3x returns. So those firms are underwriting very different outcomes. They just need those $1B entry prices to become $2-3B companies.

Is this the stupider game? Not necessarily! It's just a different game. So what's the stupider game? For other VCs, its not realizing that you're competing with someone who is playing a very different game. For founders, its realizing that to these firms you are a rounding error. Going from a $1B to a $3B valuation isn't always a herculean effort. But when you're at $8M of ARR? Getting to be a $3B business is such a statistical anomaly.

As a founder, at that entry price, you have now picked up the valuation stick. On the other end of that stick? The requirement to have an outcome of a certain size. If your last valuation was $100M post? Then a $300M or $400M outcome could be life-changing for you. But when your last valuation was $1B? That $300M outcome is often a failure for your investors, your employees, and you.

Choosing your investors comes with a lot of structural baggage. Your investors have expectations that you may not have. Their game has certain forces at work that require certain outcomes. And if they don't get the outcomes they hope for? It can lead to bad behavior.

The Greatest Game? Or The Greatest Con?

I mentioned earlier the fact that there are very few rules in the real world, but there are forces. I've written before about the gravity of business-building. In that writing, I mentioned a quote about Leonardo Da Vinci and how, "once he knew the rules, he became a master at fudging and distorting them."

But back to Nate Bargatze's comment; "if you're confident, you can get away with quite a bit." Sometimes too much. The lack of rules in the variety of games we play can often mean that the confidence game becomes the Rome to which all roads lead. Just a question of who can be more confident. But just remember, con man comes from the idea of a confidence man. Who plays confidence games. 😳

Perhaps the Michael Jordan of confidence games is Mr. In The Arena himself.

I don't listen to the All-In podcast. I can't handle it. But when I saw that Chamath addressed the "man in the arena" meme-storm that happened this week, I listened to that section. And it perfectly crystalized the danger in playing different games. Here's his response:

"People got upset because what I said was the truth. Telling the truth, especially when its so clear and so obvious, sometimes can really touch a nerve... There are all these people who are constantly doing things. And then we come into X and we don't confuse X with the arena. We don't do stuff in X. We talk in X. But then we go back and we actually do things. And success is never guaranteed. But there is a small strain of people who just violently hate themselves, or hate the fact that you're doing things, and then that you talk about them... I just wanted to take a direct line of attack on people who are constantly blaming others for everything."

Gross.

Just remember. This was in response to people saying, "hey... we believed you. You told us to buy into these SPACs. And we believed you. We had confidence in you. And we lost everything." His response was "I didn't inflict any losses. Do your own research!"

Also, it was hilarious to me that, when describing the meme-storm, Calacanis only showed a meme of Chamath superimposed on Russell Crowe in The Gladiator looking ✨so badass✨. I prefer this meme, which seems to more accurately reflect Chamath's response:

But he didn't cause losses on Twitter! These weren't memes, or hurt feelings. These were people who listened to a guy who said "trust me. Have confidence in me." And then listened, and lost their money. And he goes on to call them "f*cking losers" if they're not trying things and ✨iterating✨.

But now we come back to the danger of playing different games. Because, as much as it makes me throw up all over myself, I have to say I agree with Chamath. He didn't cause losses per se. He played a game. And he played his game well. Did he screw hundreds, maybe thousands of people in the process? Yes. Did he make off like a bandit, while leaving employees, investors, and shareholders in the mud? Yes. But he played his game.

Do I approve of his game? Hell no. Do I want to play his game? Absolutely not. But his game is not even the stupider game! Is it an awful game? Yes. Is he an absolute ass-hat for playing his game? Indeed. But is it a stupid game? If the goal of the game was to make millions of dollars, then no. It wasn't a stupid game. Maybe an evil game. But not a stupid game.

So What Is A Stupider Game?

Stupider games are not realizing that other people are playing different games. OpenAI is playing a different game. Capital agglomerators are playing different games. Chamath is playing a different game. One of the biggest obstacles to most of the systems in the world, whether its healthcare, criminal justice, mental health, housing, or capitalism itself—all of them are filled with people playing different games.

Quick tangent with a caveat to conclude.

My kids are vaccinated. We got the COVID vaccine. I don't hate vaccines. But honestly, I understand where the conspiracy theories come from when it comes to healthcare. Something feels off because you start to feel the sneaking suspicion of someone else's profit motive. In Jim Carrey's infamous CNN discussion on autism and vaccines, he said it pretty clearly:

"I don't think we can afford to assume that the people who are charged with our public health any longer have our best interest at heart all the time."

I don't believe that conspiracy theory. But the same skepticism of the healthcare complex, the military complex, the prison industrial complex, all of these things are based on the skepticisms derived from other people's profit motives. In other words? People feel like they've been playing stupider games. And they're trying to wake up to understand what different games other people are playing. And how those games impact their own games; their own lives.

In the world of building and investing in companies, there are a LOT of different games at play. The only way to avoid finding yourself playing a stupider game is to look around and understand the games that everyone else is playing. And adjust accordingly.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Wow, solid essay with very clear examples and expanded on topics. I have a saying that "you can't play a game that you don't know the rules for". Perfectly fits with having to known what game you are playing, whether or not you decided or got put into the game without your consent. Having agency could be a good follow up piece since agency and self awareness like you said, are the only ways to avoid being some else's sacifical pawn

This is really well written.