This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I'm not very good at planning and setting goals. But I have an incredible imagination😉. Which often leaves me subject to disappointment. A few days ago, I was tossing and turning in bed, feeling overwhelmed by all the categories of things I didn't feel I was doing well enough at. But in my mind, a plan started to weave. I had this vision of what I would do, how I would lay out my goals, actions, outcomes, and finally get on top of my seemingly overwhelming to do list.

The plan sounded great. Then I woke up. And 100% of it was untenable.

I think often of a quote from Mike Tyson, when asked if he was worried about his opponent's "fight plan." Tyson's response was “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” Whenever I think about the face punch that is reality, I think about this quote. So much of life is formulated in some shape or form as a "plan." But reality is, for everyone, a punch in the face. You're always surprised because life is unpredictable.

Not to go too deep down the boxing rabbit hole, but the rebuttal comes from another world champion boxer, Mr. Rocky Balboa himself:

"You, me, or nobody is gonna hit as hard as life. But it ain't about how hard you hit. It's about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward. How much you can take and keep moving forward."

Being surprised by life is inevitable. What is determinable is how we react when things don't go according to plan.

The Land of Unicorns

In the last ~3 years, we've seen hundreds of companies reach unicorn status. Many of them are now armed with their $1B+ valuations, years of runway (maybe), and in almost every case, less than $100M in revenue. I can't tell you the number of companies I saw raise at $1B+ valuations on <$5M of revenue.

A lot of VCs are predicting that many of them will fail, in some instances as high as 50%+. I also think that a lot of companies who are overvalued are going to face a significant punch to the face. Many of them are reacting dramatically to the changing market. But I've been surprised how many are sort of going along business as usual. So I started to put down thoughts on how that might play out, for better or worse (mostly worse).

For many of these companies, the biggest reality that they will have to face is that for most of these companies, any valuation mark from 2020 - 2021 aren't just one of many data points. They're irrelevant data points.

In the words of Bill Gurley, "forget those prices happened."

As I reflect on the most likely causes of death for a company in the current market correction, there were a few key areas that came to mind:

Misunderstanding investors expectations

Avoiding down rounds

Being unwilling to control burn

Being uncomfortable with layoffs

Investor's Expectations

As much as VCs want to be partners in helping you build a business, at the end of the day their business only works if they're realistic about what your company can eventually be worth. That equation dictates the entirety of their returns. No matter how helpful you find them, or how impactful they are on your business, if your company doesn't go on to be worth more than they paid, then they don't make money.

One of the things I've often been surprised by is that investor math isn't always common knowledge or very obvious for founders when they think about why investors are looking at the valuations they are. So here's the basic idea behind most investor's back-of-the-envelope math.

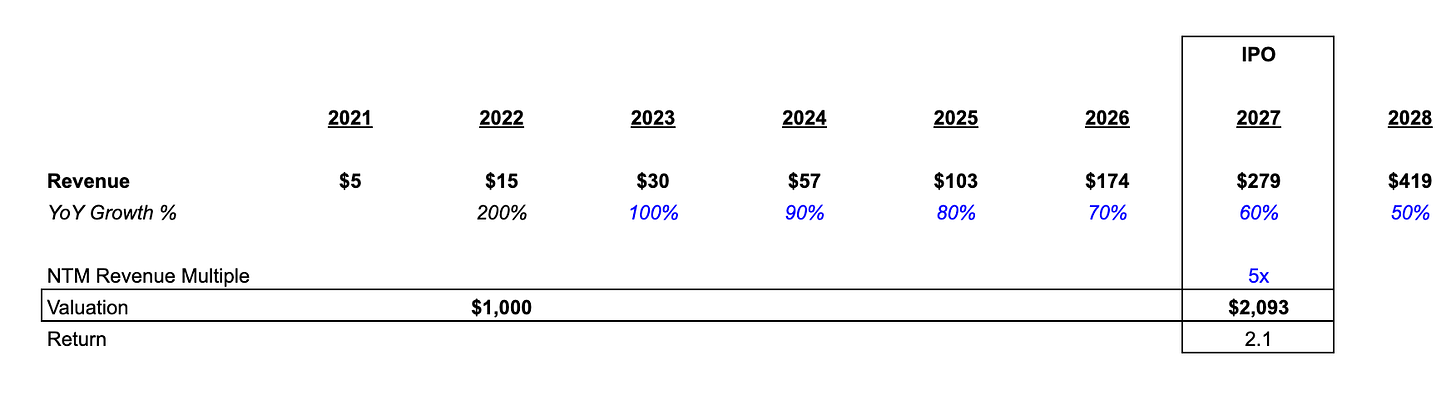

Lets say you're a Series C company at $15M in revenue at the end of 2022, growing 200% year-over-year. You got preempted 3 times in 2021 so you went from seed to Series C in one year, and now have $150M in the bank.

Then let's say over the next 5 years you see your growth slow from 100% to ~60% (pretty normal) and in 2027 you look at an IPO. If you could trade at 10x NTM revenue, you could be a $4B+ company, expecting $400M+ of revenue, growing 50%. If your Series C was $1B it could be a solid return for your investors.

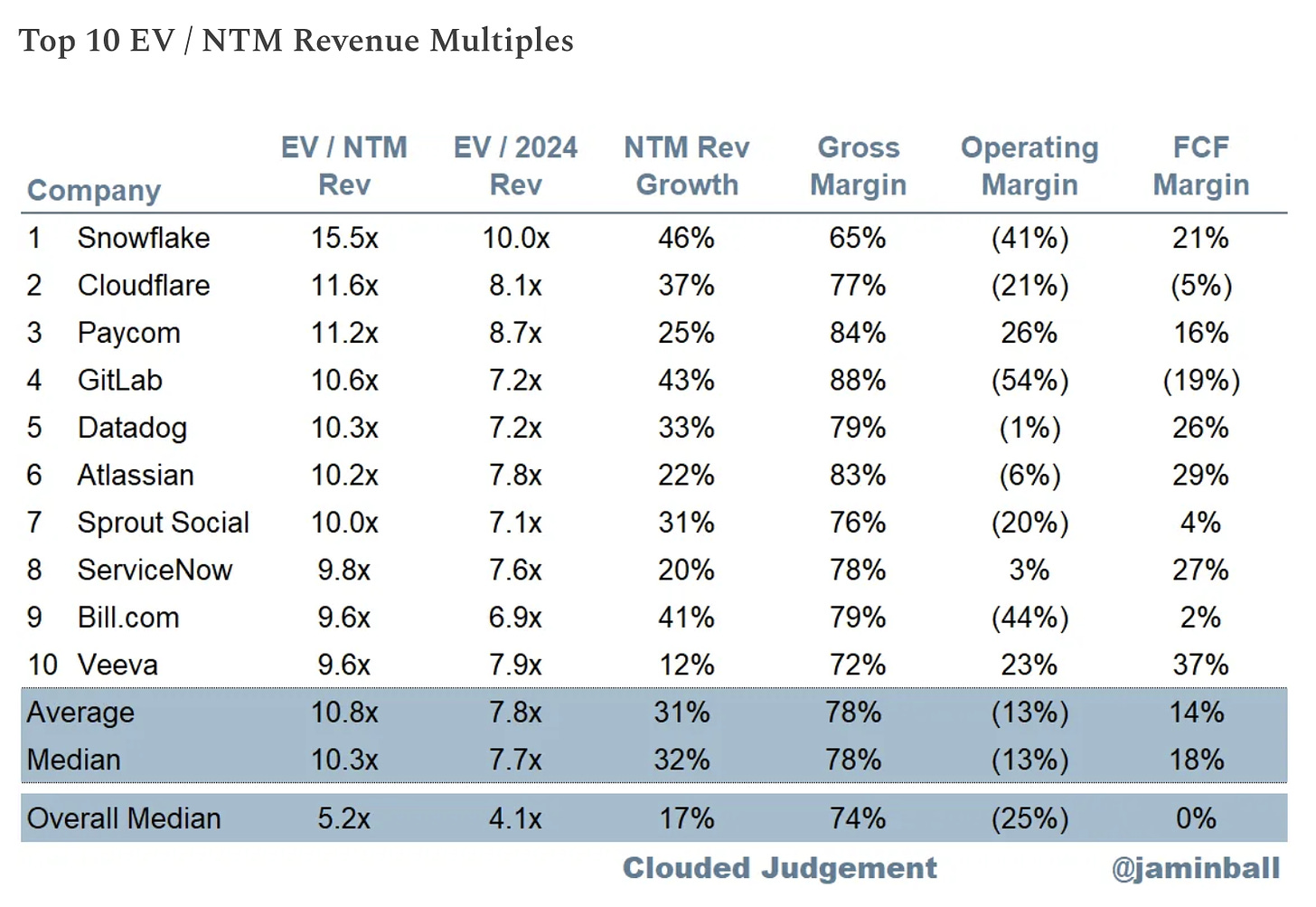

But here's the thing. Only a small handful of the top 10 companies by valuation multiple are trading at 10x or more. On average? Companies are trading at 5x NTM revenue.

Granted, the macroeconomic market is unpredictable and who knows what the future will look like. But banking on a better market in the future is what go us into this mess. As Bill Gurley points out, anything above 10x is just unreasonable.

Okay, so now you're expecting $400M+ of revenue, growing 50%, and trading at 5x NTM revenue. Now, you're worth $2B, up from $1B. Not much of a return even after adding hundreds of millions in revenue.

And this is far from an intellectual exercise. A number of companies have had this same experience seeing their valuation flatline even after significant execution and growth. The public markets are a perfect example of a goal post that keeps moving. As your growth slows, or your margins don't improve, or customer sentiment turns against you you'll find a very different environment and appetite for stock in your company than you might have expected.

Today, investors have some specific expectations about unit economics, profitability, and overall performance. Granted, for some of them that's also a moving target. They're not exactly sure how to price certain rounds or types of companies. But due diligence has made a roaring comeback.

Those expectations are shaping investors view of what valuation makes sense. The significant gap between investors expectations and founders expectations will keep the funding market moving slowly, if at all.

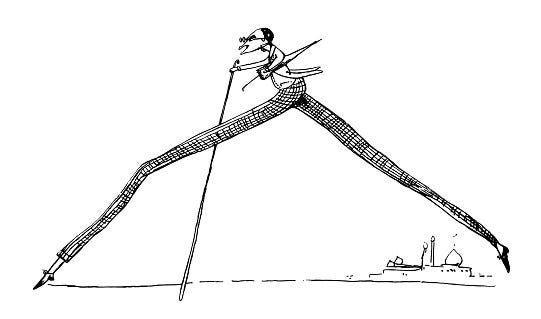

Think of it this way. Valuation and traction are like your left and your right leg. How far you step out with your right leg is your valuation. If you only take a small step forward on your left leg (traction), then it becomes that much harder for your right leg the next time you take a step. The same is true of raising a round. Investors will be expecting you to take full steps in order to justify another full step on the valuation leg.

Without recalibrating your understanding of those expectations, you're likely to find yourself flat-footed. And if you can't adjust quickly enough, you’ll be cut off from capital you might need to stay alive.

Avoiding Down Rounds

In conversations I've had with founders, there is a meaningful psychological aversion to down rounds, and for good reason. The reset in equity can completely demotivate your employees, investors, and usually yourself as a founder. But the reality is that survival may often require getting knocked down pretty hard (remember reality's punch in the face?)

Down rounds are the uncomfortable equivalent of public market price corrections. One reason raising a down round can feel so much more psychologically painful is you have to WORK for them. In the public markets, stock price just sinks regardless of what you do, for better or worse.

For most high growth tech companies, debt is a pretty limited option, especially when you're burning ~$5M a month like many of these companies are. Even convertible notes can be a pretty expensive source of capital. Sometimes you'll have to bite the bullet and be willing to take a significant down round if traction isn't keeping up.

Holden Spaht, a Managing Partner at Thoma Bravo, put it this way:

"The truth is, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. The funding route you take has enormous consequences for the future of your company, and so it shouldn’t be clouded by ego or driven by media appetites."

Granted, it's worth noting that technology private equity firms, like Thoma Bravo, are poised to make a killing in a market of good assets that are overpriced and looking for alternative sources of capital to growth-focused venture. They've already started getting after those types of opportunities in the public markets with buyouts like Ping Identity and Coupa Software. They want founders to open up to the idea of selling their business vs. raising another round (assuming its a solid business, that could use some fat-trimming).

When you think about the mechanism of a down round, that re-pricing activity is effectively the law of supply and demand at work. What is the "demand" for stock in your company? Almost every company has a clearing price where people who weren't interested before, are interested now. Market participants are going to do what they see as in their best interest, and the prices of different assets are going to reflect that.

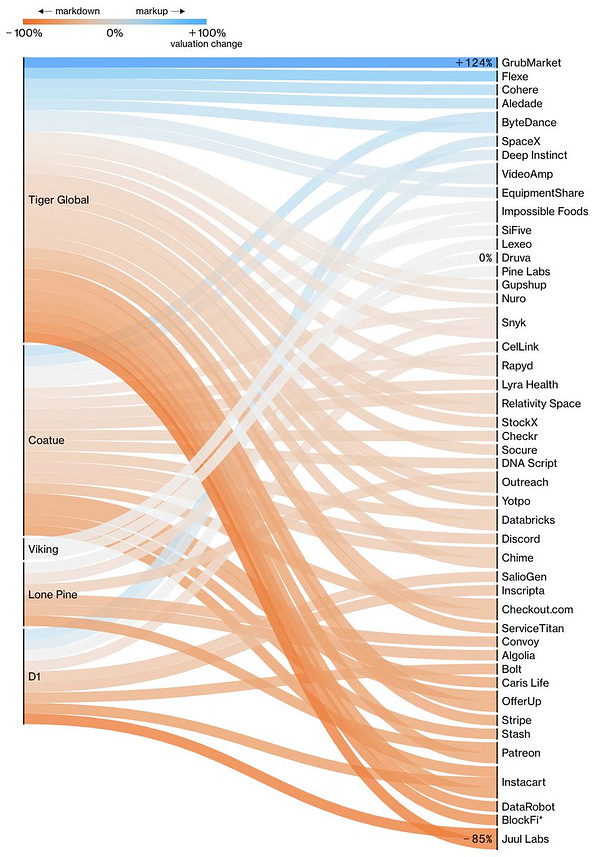

Hedge funds and mutual funds that manage more liquid pools of capital have certain requirements that force them to disclose their internal valuations for private companies more often. In a recent Bloomberg article, they laid out how some of the private companies have faired who raised from these types of large crossover investors. For the most part, it ain't pretty.

Secondary markets are another pulse showing the lack of demand that investors have for these overvalued companies. In a Crunchbase article (that has strangely been deleted since), they mentioned two secondaries marketplaces and the trends they've seen recently:

"Many tech companies have performed mass layoffs and cut costs in the past year in an attempt to cling to their valuations. But those valuations are all but worthless on the secondary market, where it’s all about what a buyer is willing to pay for a slice of a private company. In November, Forge Capital saw companies trade at around 47% lower compared to valuations set with their most recent rounds of funding. EquityZen reported stocks were trading at an average of 40% lower."

Sometimes a down round is the only way to reset your price, which will then increase investor demand. Like I mentioned before, over the last few years I saw dozens of companies raise at $1B+ valuation with <$5M ARR. Those companies probably couldn't raise for more than $300M now.

If you can grow into your valuation, do it. But if you're looking at your cash, your traction, and where you need to be for a next round and the math isn't adding up you may not be able to ignore a down round.

Unwilling To Control Burn

I've been pretty shocked by the number of companies I'm hearing about where burn is still incredibly aggressive. A lot of this comes from over-confidence in a company's "War Chest." Many of these companies that raised multiple rounds super quickly have $100M+ of cash on their balance sheet.

They'll do the simple runway math: "I have $150M, I'm burning $5M / month, so I have 2.5 years of runway!" But let's go back to our forecast with the Series C company at $15M of revenue. And let's say they don't want to run out of cash so they raise in 2 years (when they have $30M of cash left, assuming they don't increase burn). Where are they at that point?

It's the end of 2024. You're at $50M+ revenue, growing 90%. But you're burning $5M a month ($60M a year!) If you try to raise a $100M Series D, that only gives you another ~1.5 years of runway. If the VC market hasn't changed from 2023, you might not raise.

The other thing that people aren't being as cautious with is the impact this environment is going to have on financial performance. A lot of companies have seen exceptional growth over the last few years, often seeing 10x revenue growth in the early days with seemingly little difficulty.

But what if, instead of growing 100% in 2023 and 90% in 2024, you see significant uptick in churn? Longer sales cycles? Now your growth is worse, and burn is only going to get worse if you have less revenue coming in to augment your cash balance. What if your top customer is 20% of your business, and churns? What if your top competitor gets bought by a public company, and they can afford to drop prices when you can't?

A lot of companies will find that they have less of a war chest, and more of a leaky cash bucket. If you're a founder, and don't have a handle on exactly where cash is going? That's a problem. If you're on an executive team and you're not having discussions about burn? That's a problem. If you're at a company continuing to hire and spend without any discussion of runway? That's a problem.

Uncomfortable With Layoffs

Even for those companies willing to look for fat to trim, a lot of founders will dogmatically avoid headcount reductions. The impact to morale, the promises they've made to employees, the knock on productivity... In their mind, it's not worth it.

When you read about big company layoffs in the news, the numbers can feel staggering. Thousands of people impacted! But in the context of the overall business it’s a small percentage of overall headcount. Those are often over-blown as negative signal for large public companies, even though for each of those individuals it's heartbreaking.

But for a startup, you feel it much more. Having 200 employees and losing even 15 can feel personal for everyone. A lot of founders don't want to break promises they've made to employees, or damage their livelihood, or face the negative press in having to let people go.

But when it comes to company survival, everyone has a responsibility to push for relentless execution. Even when it's painful. A "shared common goal" and willingness to be relentless in pursuit of survival are table stakes now.

This is a topic worth a full post, but if you're working in a startup and don't want that relentless pursuit of survival? That's okay. There are other jobs that are more secure. But the statistical likelihood of death working at a startup (which was already quite high) has increased in the last year.

Founders have to understand that if the options are (1) negative implications of layoffs / down rounds / spend reduction, or (2) death? It shouldn't be as difficult decision, even if it will lead to a lot of difficult discussions.

What Does This Mean For Venture?

As I reflect on the companies I work with, I see a lot of people who are proactively evaluating their current financial picture, their unit economics, their runway, and adjusting their plan to ensure survival, even if it sacrifices some aspects of the growth path that they've been on. Even for companies who haven’t seen an impact on their growth and performance, they’re being thoughtfully cautious.

It is also important to note that VCs are largely to blame for the period of excess. The "fear of missing out" on a massive outcome drove capital providers to throw money at companies that not weren’t ready for it, but also used tactics to convince founders that they were ready.

Bill Gurley's thread continues to be the best I've seen on the lessons that need to be unlearned from the last few years. The reality is that companies have always needed to justify their long-term existence, independent of the appetite in the capital markets. A company whose ability to survive is dependent on a market that is fickle with each quarter is unlikely to be a sustainable business long-term.

Venture investors need to do a better job of helping companies understand the criticality of survival. Immortality was on the wind a lot over the last few years, but for those who aren't careful — the winds have changed, and death is on those winds.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Very thoughtful writing. Great article! I too love that Mike Tyson quote hehe.

Great post.

However, I would be a buyer of that IPO in the $2b scenario.

Why?

The math (EV of $2,093m, $419m ARR = 5.0x at 50% growth) shows an EV/Rev/Growth of 0.10x.

Sector median EV/R/G is 0.27x today (per Meritech comps table). So a 63% discount. Good risk reward for the IPO buyers.