This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I’m quite late today on two accounts. First? I’m about 27 hours later than usual because I was enjoying a weekend with the very talented community in Contrary at our annual retreat. So this piece is dedicated to all those folks whose company I got to enjoy this weekend.

I’m also about a week and 27 hours late because I wanted to write this piece the Saturday before Labor Day. This piece represents almost 10 years of me collecting notes and thoughts on unions, and labor, and work. Unfortunately, even with a near 10 year runway, I still couldn’t land the plane just right. But I imagine I’ll look back on this piece each Labor Day from now on. And after 9 different labor days coming and going, leaving me disappointed that I didn’t write this piece, I can now feel a bit satisfied.

Alright. On with the piece.

The Podcast That Started It All

Memory is a funny thing. I often can’t remember someones name by the time I’m done shaking their hand but I can remember exactly where I was when I listened to a random podcast almost 10 years ago. That's exactly what happened in April 2015 when a new episode of Planet Money came out. The title was The Square Deal. I didn't know much about the topic, but I hit play.

That podcast episode is what put unions on my radar. Ever since, I've carried a folder or tag across Evernote, Notion, and finally Roam, collecting different quotes and ideas about unions. Every Labor Day since 2015, I've thought "I'd like to write about this stuff." Yet, every Labor Day comes and goes, mocking me for my inadequacy. Well, hopefully today is the day I put that self-doubt to rest.

Now, I'm not gonna lie, unions were never something I thought about growing up. My Dad wasn't part of one and if my grandpas were in chicken ranching or forest ranger unions, it never came up when we were playing cops and robbers.

Instead, what struck me about the podcast episode, and probably solidified it in my memory, was the initial discussion of something I've written about again and again and again. The topic? City building.

The episode tells the story of George F. Johnson, the co-owner and president of the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company. As George F.'s Wikipedia page explains:

"Endicott-Johnson was the first company in the shoe industry to introduce the 8-hour workday, 40-hour workweek, and comprehensive medical care. This 40-hour work week was a unit-production based wage rather than an hourly based wage. Despite paying some of the highest wages in the industry, Endicott-Johnson was consistently profitable."

For his employees, George F. created a new kind of town. Workers could live there and he built libraries, parks, hospitals, golf courses, swimming pools, merry-go-rounds, theaters. All for free, or very low cost. Healthcare was totally free. Every baby born to an Endicott-Johnson employee was given a bank book with $10. The Endicott-Johnson company got into the business of building affordable houses, selling each employee a house at a net loss to the company of $1K.

He called all of this "the Square Deal."

This seemingly utopian-esque town was what initially caught my city-building eye. But George F., as a leader, is what really stuck with me. There's a radio speech recording the episode plays of him where he lays it out clearly:

"I want you to understand. Everything you have done has made everything I have done possible."

Even when the Great Depression came, George F. made an announcement:

"We're not going to lay anyone off, we'll just take what we can get. There are fish in the river and dandelions on the hill. We'll have to live on that."

Despite the promise of not getting rid of anyone, it meant that each worker was getting fewer hours and less pay. As a result, Endicott-Johnson started to get pulled towards the same labor movement that was sweeping the country as workers fought for better pay. When Endicott-Johnson workers started talking about unionizing, George F. went down to talk to them "with tears in his eyes."

"You don't need a union. They can't give you anything more than I can give you."

Eventually, 15K workers went out to cast a vote for or against the union. At a time in the US when the vast majority of workers were unionizing, often in violent demonstrations, and while the US was passing legislation like the Wagner Act to make organizing even easier, the Endicott-Johnson company saw a whopping 80% of its workers vote AGAINST the union. George F.'s Square Deal had kept them loyal.

When the rest of the country was boiling over with labor violence, and union strikes, George F. took pride in saying "it doesn't happen here… We've proven that labor and capital can live in harmony."

You can see how this story captivated me! In an age of robber barons, you have this one man who believed it was the “responsibility of the modern, progressive up-to-date employer to take care of the welfare of his employees. Really believed that if you took care of your workers, you could be more competitive!”

It reminded me of a story from the Book of Mormon where there is an ancient civilization in the Americas around 90 B.C. And the civilization is ruled by a King, but he's worried about the possibility of a future King being a corrupt ruler that would make his people suffer. So, instead of passing his Kingship down to his children, he organizes a system of judges with higher judges and lower judges that sound quite a bit like the checks and balances in the US.

In explaining to his people why this move away from Kings he says, in effect, "if it were possible that you could have just [rulers] to be your kings, then it would be expedient that you should have a king." If every company could be run by a George F., then we wouldn't need labor unions and collective bargaining.

But alas, we don't. Yet, despite the increasing reality that we do have unjust people controlling how people work and are paid, unions are still not all they used to be. So, after years of collecting notes, I tried to dig into why, and whether that's a good thing? Or a bad thing?

So you were born in the 90’s and don’t know what a Union is…

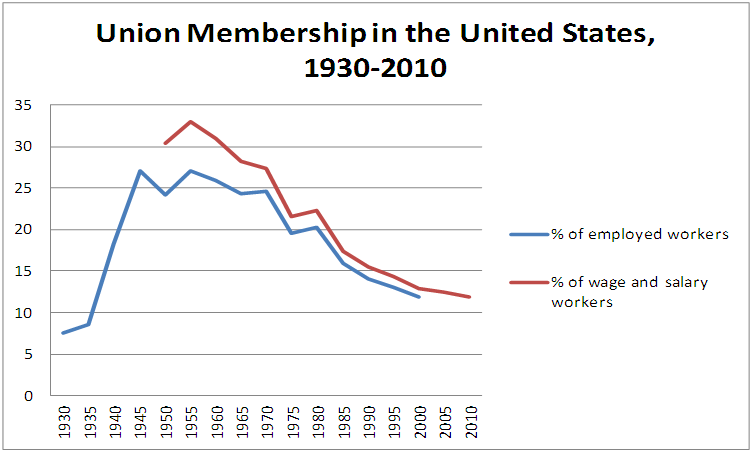

For a lot of folks, one of the reasons you might not know much about unions is because they've gone down dramatically, both in power and prevalence. Like I mentioned before, the Wagner Act of 1935 was passed to "guarantees the right of private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, and take collective action such as strikes." As a result, you saw a massive uptick in union membership from <10% to a high of almost 35% between 1935 and 1945. But it didn't stick.

That chart ends in 2010, but as of 2023 it was pretty close to the same, with ~10% of workers in the US belonging to a union. There are a number of drivers in that decline, from offshoring industrial and manufacturing capacity to globalizing the labor force, automation, and a decline in public perception after corruption scandals like Jimmy Hoffa's ties to organized crime in the 70s.

In particular, employer pushback against unions has gotten more and more aggressive. I remember reading Nickel and Dimed in high school and feeling the sarcasm dripping off the page as she described Wal-Mart's anti-union training as they're watching a video called "You’ve Picked a Great Place to Work":

"Here various associates testify to the 'essential feeling of family for which Wal-Mart is so well-known,' leading up to the conclusion that we don’t need a union. Once, long ago, unions had a place in American society, but they 'no longer have much to offer workers,' which is why people are leaving them 'by the droves.” Wal-Mart is booming; unions are declining: judge for yourself.

But we are warned that 'unions have been targeting Wal-Mart for years.' Why? For the dues money of course. Think of what you would lose with a union: first, your dues money, which could be $20 a month 'and sometimes much more.' Second, you would lose 'your voice' because the union would insist on doing your talking for you. Finally, you might lose even your wages and benefits because they would all be 'at risk on the bargaining table.' You have to wonder—and I imagine some of my teenage fellow orientees may be doing so—why such fiends as these union organizers, such outright extortionists, are allowed to roam free in the land."

I remember reading a book in 2017 called What You Should Know About Politics . . . But Don't that had an interesting section on labor and social security. One of the points that struck me in its overview of unions was where some of the criticisms came from:

"Labor laws are costly because meeting and enforcing the regulations add to the expense of doing business in the United States. If you want to manufacture a manhole cover in America, it's much more expensive than it would be in India, where workers aren’t even required to wear shoes in a metal foundry. Some industries’ unions are often harshly criticized: the favorable and expensive concessions on wages, pensions, and health care won by the United Auto Workers in Detroit are seen by many as a reason that low-cost American cars have lost ground to Asian makers since the 1970s."

Teacher's unions, in particular, get similar criticisms. The idea is that, because teacher's unions emphasize seniority over capability, it makes it basically impossible to get rid of underperforming teachers. In the book, The Smartest Kids in The World, the author, Amanda Ripley, follows several American exchange students to Korea, Finland, and Poland to experience other, higher performing education systems. One of the things that struck me was a comment from a teacher in Finland in conversation with Ripley:

"When I asked him if he had any advice for the United States, he said: “You should start to select your teachers more carefully and motivate them more. One motivation is money. Respect is another. Punishing is never a good way to deal with schools.” Autonomy mattered as much to [this teacher] as cash."

In a similar conversation about the principal at the school in Finland, Ripley made this point:

"In her eight years as principal, [this principal] hadn’t dismissed any of [their] permanent, full-time teachers. As in the United States, Finnish teachers almost never lost their jobs due to their performance. They were protected by a strong union contract. However, it was easier to manage inflexible workforces if employees arrived at work well-educated, rigorously trained, and decently paid from day one."

When I read that book (also in 2017), I wrote down a note to myself, saying "unions work well when the employees are well trained. When they become shackles that tie employers to bad employees they will never be super popular." And that reminded me immediately of George F. Johnson, believing that if you took care of your workers, you could be more competitive! Being able to achieve consistent profitability "despite paying some of the highest wages in the industry."

All of this context on unions, both for and against, may very well not be context you're familiar with. I know each time I discovered a new nugget about unions it felt new for me.

One of the reasons a lot of folks in the tech world may not be as familiar with unions is because we just don't have very many of them. Though, a few of the more ambitious tech companies that have ventured outside of cyberspace into the real world have occasionally run into these types of organizations.

"I Dabble"

You could argue that unions and tech aren't typically in the same sphere. But the collective tech community certainly dabbles in unions. One of the most union-exposed tech companies in the world is Amazon.

Before 2014, Amazon had been dependent on USPS, UPS, and FedEx for deliveries. To try and improve that part of the experience, Amazon began formulating a way to build out their own last mile delivery logistics network. Despite the fact that this would involve a massively complex web of logistics across their 244M customers at the time, the complexity wasn't their biggest concern. It was unions.

In the book, Amazon Unbound, Brad Stone points this out:

"Delivery stations would have to be placed in the urban areas where most of Amazon’s customers lived—places like New York City and New Jersey that were the locus of the organized labor movement."

Rather than implicate themselves with the complexities of a union, Amazon created "arm's-length deals." Stone goes on to explain:

"[Amazon] wouldn’t directly hire anyone but instead create relationships with independent delivery companies—DSPs (delivery service partners)—that employed nonunion drivers. That would allow it to pay lower labor rates than UPS and to avoid the prospective nightmare of drivers bargaining collectively for higher wages, which could destroy the already fragile economics of home delivery.

Such arm’s-length deals with drivers would indemnify Amazon from all of the unseemly and inevitable corollaries of the transportation business—such as botched deliveries, driver misbehavior, or worse, car accidents and deaths. Economists called this kind of arrangement, where companies outsourced specialized forms of work to subcontractors, “the fissured workplace,” and blamed it for eroding labor standards and fomenting a legalized form of wage discrimination that exacerbated inequality. This was a decades-long trend propagated not just by transportation providers like FedEx and Uber but by hotels, cable providers, and other tech companies like Apple. Amazon’s size, of course, spread it that much further, and policymakers, whose job it was to protect workers, were caught flat-footed."

Throughout my exploration of unions, I keep coming back to these nuanced arguments for and against.

Did unions help prevent things like child labor? Yes.

But did it also possibly contribute to the decline in competitiveness of the US auto industry in the 70s? Also yes.

Do unions help prevent worker exploitation in physically demanding jobs that are highly commoditized? Yes.

But could unionized labor also destroy the unit economics of things like home delivery, making it much less viable? Also yes.

Like most large corporations, Amazon hasn't been that interested in tackling the nuance. Rather than deal with unions, Amazon's typical response has been what it was "at a Seattle call center in 2000, at German fulfillment centers in 2013, and soon, in France, at the start of the deadly Covid-19 pandemic."

"In all those cases, when talk of unionization and worker strikes came up, Amazon either tamped down on growth plans in the region, temporarily shut things down, or walked away from a site altogether."

Despite their best efforts, Amazon had its first labor unionization in April 2022 when warehouse workers in Staten Island joined the Amazon Labor Union (ALU).

While unions occasionally enter the picture with tech companies that touch the physical world, whether its Doordash with dashers, Uber with drivers, or Tesla with auto workers, its by and large not something that the majority of people who are actually working with on technology itself are exposed to.

As a result, it creates a sort of "Not-in-my-backyard" or NIMBY mentality when it comes to unions. But that's been changing.

NIMBY Unionism

Speaking of NIMBYs, I'm reminded of a rumored response from a famous venture capitalist when discussing the types of people who most often belong to unions. People that work in industrial towns where labor is a core part of their survival. People that are, often, lumped together as "middle America."

“I’m glad there’s OxyContin and video games to keep those people quiet.”

So on the one hand, I feel an intense wariness of people who don’t seem to care about people who have rough jobs, make very little, and have almost no power.

On the other hand, I recognize the intense razors edge that most businesses walk in trying to make increasingly better products in a way that can still be profitable.

The problem with nuanced issues like unions is that I feel the pressure of not being able to make any hard-fast conclusion about whether or not things like unions are good. I want people to have good working conditions. But I also want US companies to be globally competitive. I also recognize the obstacles of some regulations that, while they improve people's lives here, make it impossible for US companies to compete with countries who specifically do NOT follow those same rules.

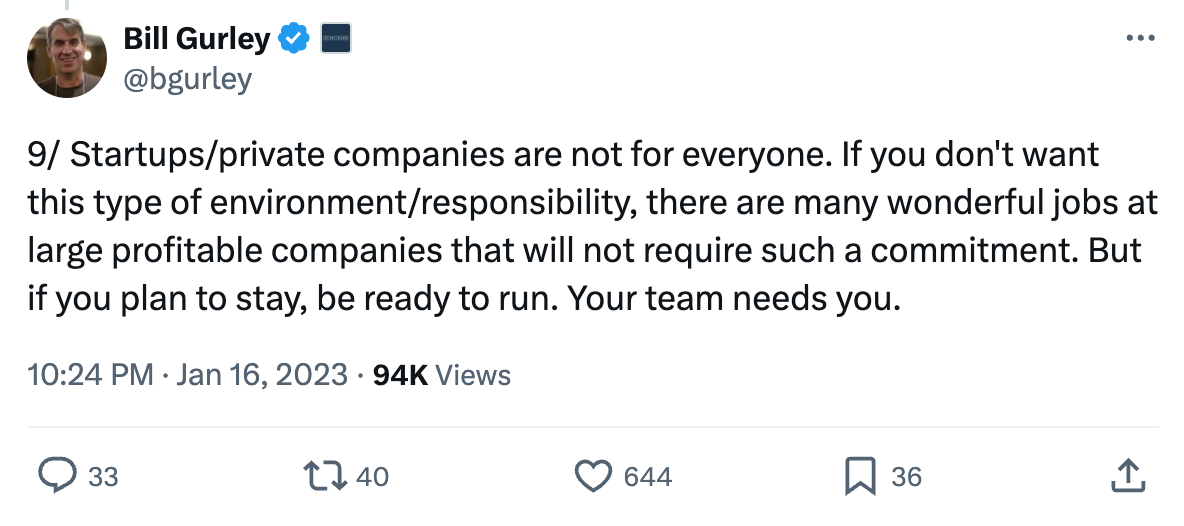

And often, the conversation of unions in tech turns to a defense of the "rise and grind" culture that should exist in startups. Immediately I feel mentally chastened by the words of Bill Gurley:

And he's right. Startups are hard work. And they require intense commitment from the people building them. In these particular incidents, there is an absolutely justified demand for people who are willing to work hard and make sacrifices. I've written about the struggle between work and life over and over and over again.

But there is an important nuance. The monikers of "tech" and "startup" for a company were, for a long time, synonymous. If you're building in tech you were, by definition, a startup. A scrappy upstart just struggling to bring your utopian dream future to life.

But that's not true today. Companies like Amazon are most certainly tech companies, but they're very much NOT startups. Amazon is the second largest company by employee count. Not largest employee count among tech companies; largest across the US. And, increasingly, companies like Target, Starbucks, etc. are becoming "tech" companies as well.

And as tech grows up and becomes less fringe, and more mainstream, that relationship with organized labor is likely to change.

Coming To a Tech Company Near You

The first driver of change will be the reality that, increasingly, more companies will touch unionized labor markets. One clear example is AI in Hollywood. A few weeks ago, I wrote a piece that pulled heavily from Mario Gabriele's piece on A24. One of the things that he touched on was right in this vein:

"Hollywood is in crisis. After more than two months of striking, the unions representing screenwriters and actors remain locked in a stand-off with the industry’s big studios. The use of artificial intelligence is just one of the issues at stake, but it casts a long shadow. Already, the technology shows signs of upending content creation as we know it."

Companies building technology for heavily unionized industries are going to increasingly have to acknowledge their impact on those groups of workers. Generative AI for things like special effects is just the latest in a series of that kind of impact.

But beyond that, there is an increasing movement within tech workers to unionize. That happens when massive employers with hundreds of thousands of workers can no longer hide behind the scrappy excuse of "startup." And, back to Bill Gurley's point, I think the "scrappy excuse of startup" is a valid one for people who are working to build a company out of nothing.

But there are a LOT of people who, even as engineers, don't want the risk and grind of working for a startup. They want to build technology in a well-organized corporation for reasonable pay and benefits, recognizing that that means less reward. But that's okay. What's not okay is for people who want to work in that situation being forced to feel like they're working for a scrappy startup. Or, even more commonly, for them to be treated like inhuman commodities that can be switched out like lightbulbs.

You've started to see this happening at gaming companies like Sega, as well as companies like Google and Microsoft, the latter of which has even said it "won't stand in the way of workers who want to unionize and signed an agreement not to interfere with any efforts by Activision Blizzard workers."

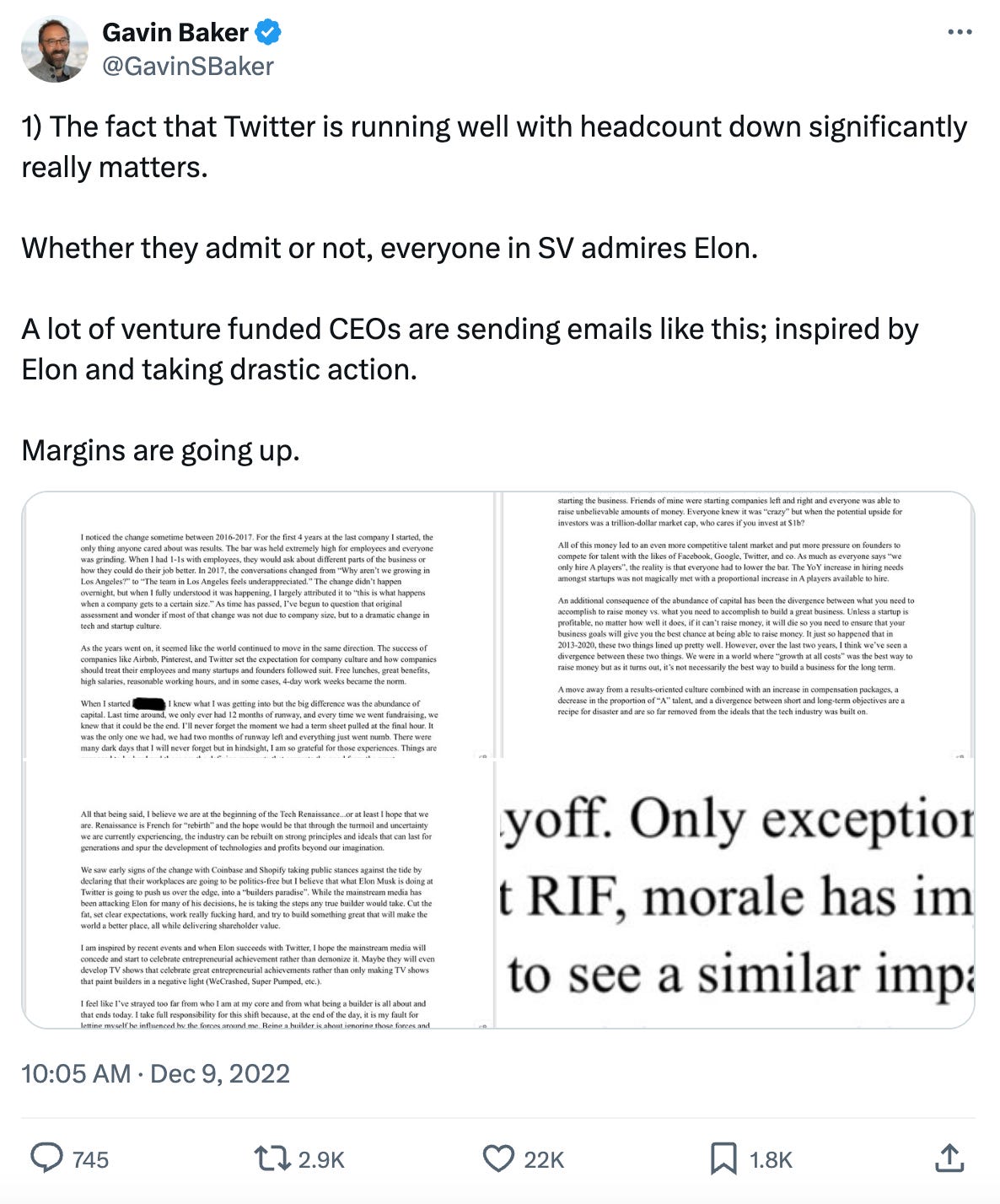

And I can hear the tweeter voices in my head; "those are just entitled engineers." Or "those are just replaceable non-essential employees." "Elon Musk fired 6K employees, and Twitter X works just fine."

This all goes back to the nuanced position these questions can contort you into. If a bunch of engineers at a Series A startup wanted to unionize, I would question the quality of those engineers. They signed up for a tour of duty and are surprised when they don't get to sleep in.

Corporate bloat, like Twitter most assuredly had, can present on opportunity for healthy and meaningful staff reductions. If Twitter was unionized, you could argue that Elon Musk's inability to fire people could have led to an even worse result for the company. There are some great perspectives out there on what Elon Musk has been doing, and what it means for the rest of us.

But you can't deny that there are situations where unions could present a meaningful mechanism to ensure higher quality working conditions for workers that are engaged in some pretty difficult work.

One such example is a group of YouTube music contractors who are employed by Cognizant, but argue that Google's involvement in their work makes them a joint employer (taking a page out of Amazon's "arms-length" employment strategy.) In April 2023, those contractors pushed to unionize.

Google's response, like most large employers when faced with unruly labor dictums, is simply to act like a Civil War surgeon and just cut off the problem. In May 2024, Google simply refused to renew its contract with Cognizant, effectively cutting off the employees in retaliation for their efforts.

And again, you could argue this is just a nuanced "cost of doing business." If Cognizant can't control / satisfy its employees, then partners like Google won't do business with them. But its a little more unfortunate than that.

Does the name Cognizant sound familiar? Some of you might remember it from a series of stories from Casey Newton that came out in 2019 where he went super deep into what he called "the trauma floor." In that piece, and another one called "Bodies in Seats," Newton delves into the truly horrific world of content moderators. People who are daily exposed to huge volumes of "hate speech, violent attacks, [and] graphic pornography."

Cognizant is a contractor for some of the largest companies and it has a rich and disturbing history of mistreating employees, brow-beating them into secrecy and NDAs, while many of them walk away with diagnosable PTSD. Is that not a group of people that deserve some support? Some collective power to avoid being absolutely destroyed?

[Dis]Union

I told you right from the beginning — I don't have an answer to this dilemma. The nuanced back and forth of labor vs. capital, basically. Its been a conflict for a long time, and I'm not going to solve it in one blog post. Not even in two. But I keep coming back to the need to acknowledge the reason why unions existed in the first place. Despite the often inefficient and occasionally corrupt results they produce, they are meant to serve a purpose.

That thinking reminded me of a piece that Nathan Baschez wrote in June 2020, around the time of George Floyd’s murder. The piece was called "What good is strategy right now?" In it, he covered a range of issues. But two paragraphs struck me as he contrasted the need for creating business value with the need for enabling quality humanity, despite the business implications:

"For example, when I read about how it’s strategic to limit the “bargaining power of suppliers” from Michael Porter, it’s impossible to not think about the history of collective bargaining in America, and how it could have helped millions of workers begin to accumulate a bit more wealth and stability, which would have had compounding effects over time, and resulted in a much more equitable society today. But the business community leveraged its power to resist the labor movement, and unions were decimated. It’s impossible to not think about the disproportionate impact this has had on black Americans, who have too often been denied management opportunities.

Of course, unions are not without drawbacks! In fact, police unions seem to be a major obstacle to solving police brutality. But most unions focus on getting workers paid more and having reasonable working conditions. Many countries have found a way for management and labor to work this out, but in the US, business owners traditionally have taken a loud and “principled” stand against the downsides of anti-competitive behavior from labor, while happily glossing over their own anti-competitive (i.e. “strategic”) and rent-seeking behaviors."

So where do we go from here? Unclear. But for me, where my mind wanders is something I've talked about before: the push for businesses and people to have to internalize their negative externalities.

Internalizing Negative Externalities

This idea of internalizing negative externalities is, I realized today, up there with other topics I've touched on a lot. From VCs to startups to governments, I've written over and over and over and over again about how one of the biggest weaknesses of these types of massive institutions is either the lack of ability or willingness to deal with the problems they cause.

In May 2024, I wrote a piece called The Value Cycle. In it, I explained an important concept when it comes to trying to understand negative externalities:

"The act of Value Creation has, in some cases, gotten a bad rap. I think this comes from the concept of Gross vs. Net Value Creation. Gross Value Creation is just taking into account every good thing that comes from a particular product or service. Net Value Creation is when you take into account the negative externalities as well. When people crap on venture capital and tech as terrible, its because they're measuring things in terms of Net Value Creation, rather than Gross.

iPhones have immense Gross Value Creation. But you get more bummed when you start to think about anti-socialization, addiction, and even the child labor leveraged to create them in the first place. Facebook, same thing. Connecting, entertaining, and informing people can have a lot of Gross Value Creation. But Net Value Creation of the service gets fuzzier.

Typically, it's too difficult to create a product or service with Net Value Creation in mind. Often, because you don't know what negative externalities will rear their head over time, or at scale. So you build the best product you can and then try to address any negative results that may come as offshoots of what you've built."

And that's the reality. Most people who set out to build technology will often set out with the best intentions. And that's good. But intentions are only part of what make up your character. Even your actions can only define so much of who you are.

When you're faced with the consequences of your actions, that's when you demonstrate who you really are. And the unfortunate reality is that the majority of large organizations who have taken upon themselves the responsibility for tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of employees and workers are typically more keen to push off the consequences of their actions, rather than deal with them.

There is some clear evidence that "income inequality is lower where the unionized share of the workforce is higher, and higher in places with lower rates of taxation."

There is some clear evidence that “the poorest 40 percent of the US population is in desperate straits. Many industrial jobs have disappeared, either replaced by technology or shipped overseas. Unions have lost their punch. The top 20 percent of the population controls 89 percent of the wealth in the country, and the bottom 40 percent controls none of it.”

Did Amazon or Google or Microsoft cause this? No. But do they have a responsibility to try and help where they can? Yes.

Think of George F.

As I wrap up my thinking on this, I come full circle back to George F. Johnson; the co-owner and president of the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company, and his Square Deal.

His ability to build exceptional living environments for the employees he cared about. Free healthcare, affordable housing, cheap entertainment and amenities. And he did all of this while turning out consistent profitability. And during the Great Depression, no less.

When whatever "job-to-be-done" unions solve for came to popular attention in the 1930s, it may have been a need for a lot of people. But not for the employees of the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company. 80% of their employees voted to say, "we trust our employer; we don't need a union."

But what happened when George F. Johnson passed away? In the words of a former Endicott-Johnson employee:

"All the sudden they were bringing in this Vice President, or that new President. 'We're not making any money on that? Lets shut that department.' And then you've got people saying, 'now wait a minute. It wasn't like that when George F. was here.'"

"If it were possible that you could have just [rulers] to be your kings…”

Gerald Zahavi, who wrote a book about George F. Johnson titled "Workers, Managers And Welfare Capitalism," added this unfortunate commentary:

"I think the Square Deal is an anachronism today. People don't expect much from corporations, period."

Breaks my heart. It breaks my heart to hear the words of George F. Johnson after he managed to convince people he could take care of them; that they didn't need a union. The hope that he had has, very much, not carried through to today:

"We have proven in this valley that its possible that labor and capital may live in peace and harmony. And I hope a great good will come from this demonstration."

So... is Zahavi right? Is the Square Deal an anachronism? Are people right to expect nothing from big corporations? More importantly... in fact, scratch that last question. The only thing that matters... is it right that companies can get away without offering any expectations? That they can exist without bearing the brunt of any of their negative externalities?

Especially in a world where instances of both fair treatment AND exceptional profitability were achievable… could that be achieved again? Could Tesla be more competitive, not less, if it took care of its workers? Could Amazon be an even larger, more successful company if it had hundreds of thousands of champions vs. negotiating table enemies?

Why not hold companies to a higher standard of trying to clean up their own messes? Take some of those immense resources they use to optimize clicks, conversions, or ads, and allocate that brain power and money towards creating better and better organizations. Not just higher, and higher shareholder returns.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

In Sweden, the unions say that the only technology they're afraid of is old technology. That costs jobs.

I can imagine a version of regulated capitalism where unions are irrelevant but I don't think we live in that world nor am I sure I want government deciding all of those tradeoffs. So overall let the government set the basic floors on employment law and then let workers organize and negotiate for more (collective bargaining in general seems quite essential in a modern economy).

There are absolutely examples of unions creating barrier to competition, pushing for their own version of regulatory capture, and behaving in ways that are corrupt. But same applies to companies and CEOs.

So I believe I come down on the side of "unions with guardrails" versus no unions.