This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Movies are my thing. From the age of 10 to 19 all I wanted to do was go to Hollywood. I voraciously consumed the Coen Brothers, Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan, Martin Scorsese, Rian Johnson. I was inspired by stories like Jared Hess, a fellow BYU grad, writing and directing Napoleon Dynamite for $400K and making $46M.

The main problem was I was never a very good filmmaker. My magnum opus was Pokemon Love Song. Good... not great. But that hasn't stopped me from being obsessed with movies.

Even in this blog, as a way to explain my thinking, I've talked meaningfully about Children of Men, Idiocracy, Serenity, Time Machine, Logan, Her, Arrival, The Butterfly Effect, Midnight in Paris, Lincoln, Tom Sawyer, Night at the Museum, The Last Unicorn, Secondhand Lions, and a bunch of others.

What an odd filmography.

One of the things I find myself pondering often when it comes to movies has direct implications for how venture capital is playing out as well. I've written about this twice before.

First, in The Death of a Venture Fund from May 2022, I touched on how the focus on bigger outcomes is limiting more risk-taking and experimentation:

"VCs are facing the "Big Budget Effect" that is plaguing Hollywood studios right now. In the year 2000 you had just three movies that had made $1B+. Titanic, Jurassic Park, and Star Wars Episode I. Today you have 45+ movies that have made over $1B, and some of them have made $2B+ like Avengers and Avatar.

As a result of these much larger outcomes we've built a movie-making system that is focused on big hits because the business model can't really absorb too many massive flops. So you get sequels, prequels, and spin-offs. Established IP and bankable stars. No big risks. And you don't get nearly as much experimentation, innovation, or creativity.

The same is true in venture. With such big funds and such fast deployment cycles its so much more difficult to take big bets on much riskier technology. But as the world becomes more capable of building technology VCs will have to earn their big fees by chasing ever bigger "unknowns." If they don't? They may miss out on the next internet."

The second time was in The Existential Dread of Cognitive Dissonance from July 2023 where I unpacked how the size of the model can dictate the quality of the "quests" that get funded:

"Trae Stephens and Markie Wagner wrote a phenomenal piece called "Choosing Good Quests.

As it relates to my feelings about venture capital, it comes down to what we're incentivized to build. I often find myself articulating this by using Hollywood as an analogy. The "business of blockbusters" has pushed movie studios to focus on spin-offs, sequels, and reboots. While this can lead to exciting movies, it rarely leads to unique stories.

I'm reminded of a story where Steven Spielberg complained that he had almost been forced to release his film, Lincoln, as a mini-series instead of a full feature film because he couldn't get anyone to fund it! A movie made by Steven Spielberg, starring Daniel Day-Lewis! But the studio model had pushed those unique stories into the periphery in favor of massive blockbuster potential.

Venture capital is facing a similar problem. The economic model pushes for bigger and bigger outcomes, that require more and more capital. This leads to larger funds, larger rounds, more cash burn, and more exorbitant ambitions. And don’t get me wrong, I don’t have any problems with ambition! I want to see the full unlock of human potential. Automation, robotics, diseases cured, and space traversed. But the ambitions are, so often, luxury dog houses dressed up as solutions to the housing crisis.

Whether its the "big budget effect" or the "business of blockbusters," the focus of this line of thinking has always come back to the idea that, increasingly, the models of both Hollywood and venture capital revolve around "hits." The hits business is, in many ways, just a reflection of the power law. 20% of the inputs will lead to 80% of the output. But I think its more complex than that. The shape of the industry is changing under the weight of these increasingly centralized focal points.

The Silver Screen & Silicon Valley Parallel

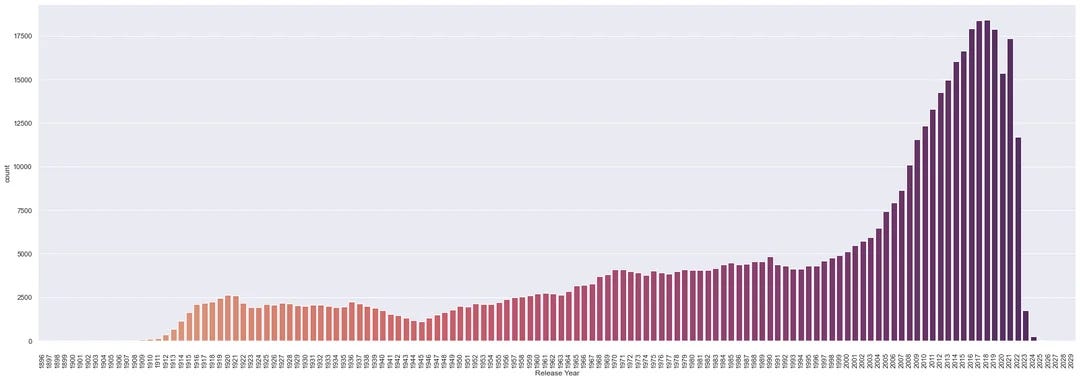

There are two charts that give off the same energy. The first is a chart showing the number of movies released over time, jumping to more than 15K per year after 2013:

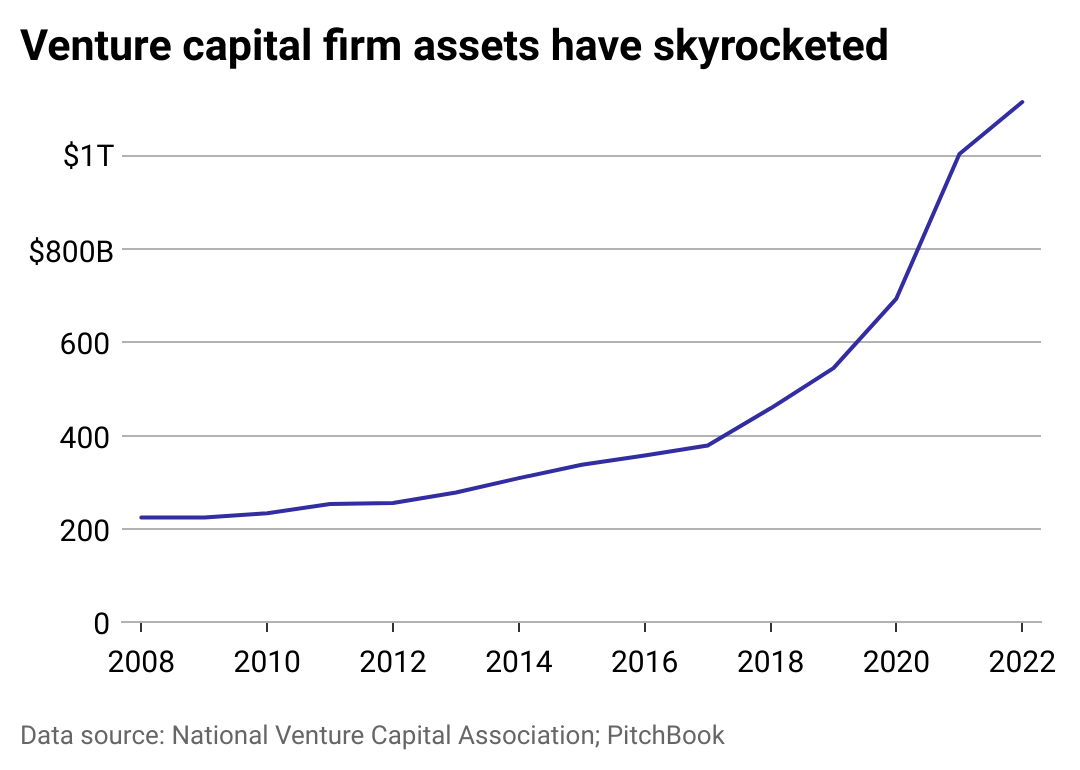

The second is the a chart showing the AUM across venture skyrocketing to $1 trillion over the last 15 years:

Something clearly changed in both of these industries to justify the shift. Granted, its several things, many of which I'm not qualified or smart enough to unpack (e.g. fiscal policy, globalization, etc.) But one thing that has certainly played a role in this rapid acceleration is the increasing consistency of hits.

For tech, it was the rise of FAANG (or whatever we're calling it these days). In 2012 the only tech company in the top 10 names in the Fortune 500 was HP. Today, that same list has Apple, Amazon, and Alphabet with a long line of other big successes.

For Hollywood, it was the increasing bankability of blockbusters. While Jaws, in 1975, is considered the "first" big summer blockbuster, it was more a function of exceptions vs. rules. But when you look at the highest grossing films, those that have made over $1B have certainly gotten more consistent. In the 90s and early 2000s there was less than one billion dollar movie per year on average vs. into the 2010s you saw an average of 3 per year.

The existence of big hits further justified the pursuit of big hits. And while you occasionally had big outcomes from original ideas (e.g. Titanic, Avatar... h/t James Cameron btw), the vast majority of the biggest outcomes came from sequels, reboots, and franchises.

The Power Law

Right up there with pattern recognition, the power law is one of the most frequently used concepts to talk about venture capital. So much so that one of the best books about the industry took it as its title. When people have unpacked industry returns for venture funds they often find the majority of the returns are driven by just a handful of companies out of thousands funded each year.

The same is true in public markets where, for example, a few big tech companies, like Microsoft, Nvidia, Amazon, Google, and Meta, make up almost 40% of the S&P 500. Across thousands of stocks there is so much attention and power pulled towards a select group of names.

One important distinction is that, while these select few names that make up the "20% of inputs" are critical for the market in aggregate they are not always the most important thing at the individual level.

Macro Outcomes vs. Micro Outcomes

In some cases something like a small acquisition could be life changing money for the company founders and employees. In other cases running a small lifestyle business could be a huge boon for an individual. Or even just owning real estate can make someone meaningfully wealthy.

But the larger the starting number, the harder it is to avoid the gravitational pull of the power law drivers. If you're starting with nothing then a $50M acquisition can be life-changing for you. But if you start with $1B then $50M is chump change.

Your Size is Your Strategy

I've written about this dynamic several times before in pieces like The Blackstone of Innovation and The Puritans of Venture Capital. Your fund size is your strategy. And, as I pointed out in Playing Different (Stupider) Games, is having a big fund a stupider strategy?

"Not necessarily! It's just a different game. So what's the stupider game? Its not realizing that you're competing with someone who is playing a very different game."

For many of these large funds their strategy has become "2% of the biggest number." How can they rack up the largest pools of capital possible to feed their ambition engines? In venture funds the motivations here are more opaque; its driven by the ambition of the founder of the fund or the budget demanded from a larger team strategy. But in Hollywood its a bit more transparent.

Greed is Good Growth

I'll say this again before I get ranting. Pointing out a particular strategy exists isn't necessarily the same as passing judgement on that strategy. Having a bigger fund, only investing in sequels and reboots, none of it is definitively bad. It's deliberate. And it carries a particular weight of implication. And sometimes those implications are bad or good.

In one particularly judgey piece about Hollywood's obsession about reboots, they make this point in explaining what attracts Hollywood to this tried and true method of swinging for the fences:

"The pivot to the IP Era feels simple, because it feels familiar. It’s because tidy, consistent, sustainable profits aren’t enough. There must be growth. There must be domination. There must be Shared Universes."

Most Hollywood studios are either publicly traded companies themselves, or are part of public companies. So there is the ever-present overhang of earnings calls and stock prices to contend with. That's why you see things like David Zaslav, the CEO of Warner Brothers, saying explicitly that the studio would focus on tried-and-true IP:

“We’re going to focus on franchises. We haven’t had a Superman movie in 13 years. We haven’t done a Harry Potter in 15 years. The DC movies and the Harry Potter movies provided a lot of the profits for Warner Bros … over the past 25 years.”

That was in November 2022. Despite what increasingly feels like audience fatigue with multiverses and extended universes, the profit motive reigns supreme, making the studio execs willing to say the quiet part out loud.

The AI bubble we're experiencing right now feels comparable. The audience fatigue with sequels is comparable to people's wariness with the "grow at all costs" playbook. The presence of a profit reality keeps the tenuous music playing.

Are audiences getting tired of big bulky sequels and reboots? Maybe. But then Inside Out 2 becomes the fastest movie to hit $1 billion at the box office. So we're gonna keep doing what we're doing.

Is "grow at all costs" a dangerous strategy? Maybe. But OpenAI burned through $8.5B to get to $3.4B in revenue, doubling every 6 months. So we're gonna keep doing what we're doing.

Again, I'm not passing judgement on these strategies. To each their own.

I'm not the kind of cinephile to decry massive IP plays as a bastardization of the art. In fact, I just saw Deadpool & Wolverine which was an egregious display of IP exploitation, and I loved it.

Nor am I an angry socialist that thinks tech companies shouldn't exist and we should just give everyone money. I love the concentration of capital into companies like SpaceX or Anduril because I want them to exist, and I massively respect what they've accomplished.

But here's the key difference. I don't love Deadpool & Wolverine or SpaceX or whatever just because they're big. I love them because they're good. I'm not attracted to the monopolistic profits. I'm attracted to the quality-of-life improving outcomes. But, in many cases, the pursuit of the big will come at the sacrifice of the good.

Building Big Good Outcomes

Out of the hundreds of movies I've seen in my life, I've never been more disappointed by a movie than I was by Batman vs. Superman in 2016. I can still remember the feeling in the theater as the movie ended; completely devoid of any joy or satisfaction. Was it big? Absolutely. The movie cost $300M+. Was it good? Absolutely not. And I'll argue with anyone who thinks otherwise.

There's a whole nerdy ocean of debate about Marvel vs. DC, and how they each built their respective cinematic universes. I've contributed plenty to that conversation in my life. But I'm willing to concede that even Marvel, despite a glorious run of a golden age from 2008 to 2019, fell victim to the same fallacy as DC after Endgame. The pursuit of big came at the sacrifice of good.

In the venture world I often see the same danger. People willing to sacrifice good in pursuit of the big.

Bigger funds, bigger brands, bigger teams, bigger swings, bigger outcomes, bigger capital requirements.

Does a bigger fund mean not as good of returns? Yes.

Does a bigger brand usually mean you're not as good for a specific industry or subset of founders? Probably.

Does a bigger team mean not all of them are as good of investors? Usually.

Often my sense is the people pursuing the big believe that it is mutually exclusive with the good. They're satisfied with the "good enough." But I think that's wrong. I think thats as wrong in moviemaking as it is in company building. You can build outcomes that are just as big while also focusing on what is good. Whether thats a good movie, in terms of quality, or a good business in terms of profitability, externalities, and overall outcomes.

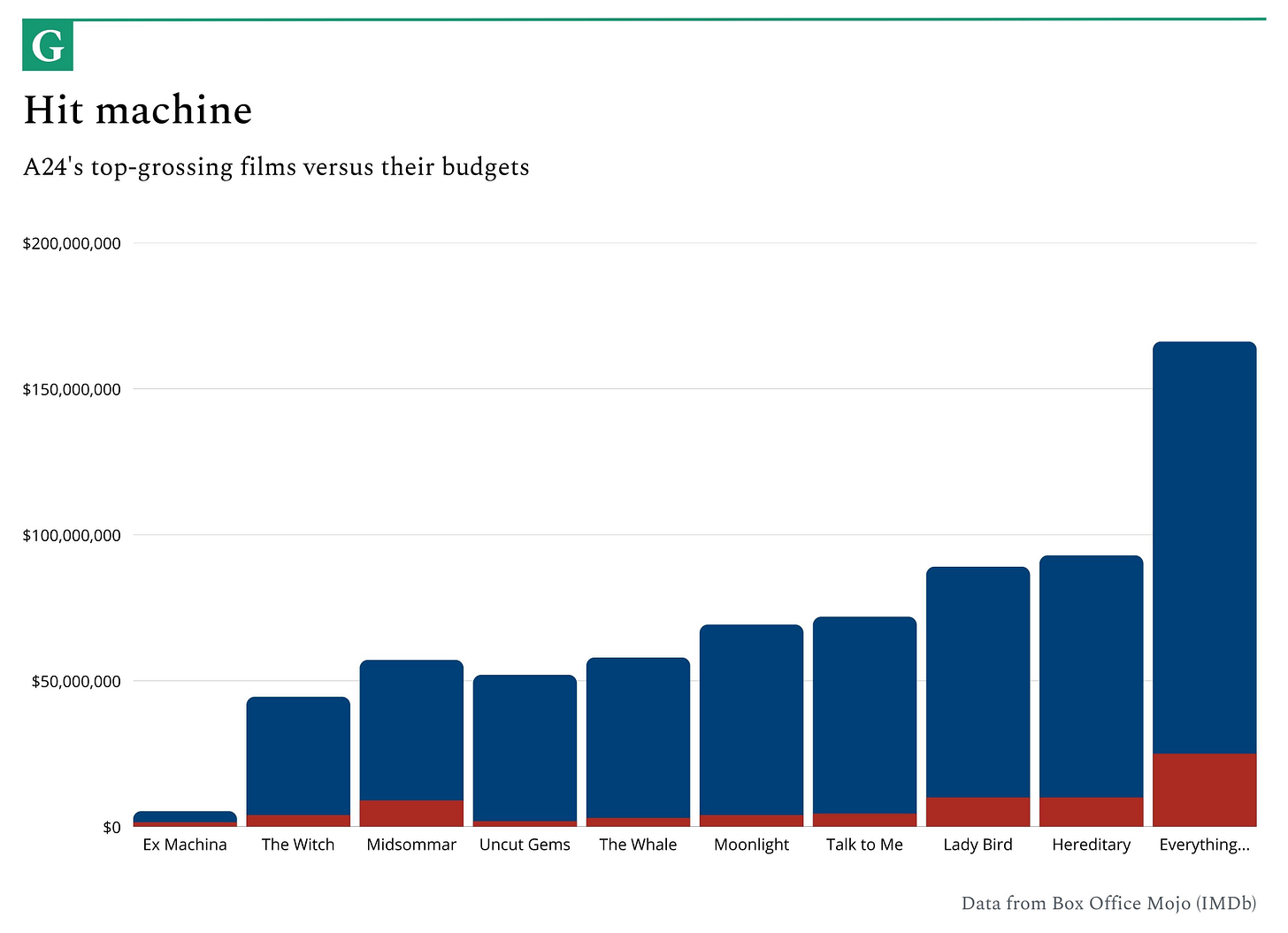

One of my very favorite pieces about the movie business came out last year; Mario Gabriele's A24: The Rise of a Cultural Conglomerate. In it, he tells the story of the independent entertainment company, A24, that was started in 2012 and went on to helped bring to life movies like Everything Everywhere All At Once, Uncut Gems, Lady Bird, and Moonlight, among others.

There is so much in his piece that I can't unpack here; you should read it. It's exceptional. But in re-reading the piece, I realized that there are several takeaways from how A24 has built its business that can be instructive for how we could improve the way companies are built and funded.

At the Mercy of the Zeitgeist

Throughout Mario's piece on A24, he makes it clear that one critical advantage the company has is its focus on embracing and understanding culture; the zeitgeist, the general vibes.

There's a whole other piece I could write on Thomas Tull's empire, Legendary Entertainment, and the formula he used to weaponize globalization, and in particular the Chinese market, to achieve sizable success. But its quite afield from what I take away from A24. Tull and other big studios have realized that they can create a better shot at bigger outcomes if they create fairly generalized, un-opinionated, mass appeal movies that can succeed in every international market.

A24, on the other hand, took the position that what the cultural vibe participants were desperate for was unique perspectives. Noticing the increasing emphasis on sequels to the detriment of original IP, the company made a bet, as Mario explains:

"A24’s founders had noticed this decay. Rather than bemoaning it, however, they spotted an opening. Just because big studios didn’t want to make opinionated indie films anymore didn’t mean that audiences didn’t want to watch them. On the contrary, amidst an increasingly homogeneous cultural landscape, projects with a genuine point of view could have an outsized impact. “Films didn’t seem as exciting to us as when we started our careers,” Katz noted. “And that signaled an opportunity.”

One key difference between a creator, like Mr. Beast or MKBHD, and a company like A24, is that creators represent tastemakers while A24 is a taste connoisseur. And in order to attract the right tastes, you have to have a pulse on the market. For entertainment, social media represented that pulse. Understanding "internet culture, fandom, and customer acquisition has been critical to [A24's] success."

That may seem obvious today but it very much wasn't in 2012 when A24 got started. "Over the past decade, no studio has more efficiently inserted itself into the online zeitgeist, seasoning our feeds with satanic goats and Oscar Isaac dance sequences."

Increasingly, A24 is taking advantage of that cultural pulse to expand its empire into TV, music, publishing, physical experiences, and cosmetics. This represents a meaningful departure from most other studios who, rather than pursuing tasteful "good," they're focused on tasteless "big." As Mario explains:

"Though many may love the stories they tell, few would consider themselves Paramount obsessives, Columbia Pictures devotees, MGM ultras. Like Disney before it, A24 is an exception to this rule. And like the House of Mouse, it has started extending its consumer relationship beyond the screen. Over the past few years, A24 has pushed the borders of its empire, moving into TV, music, publishing, physical experiences, and even cosmetics. It takes little imagination to see the contours A24 is following, to find a redux of Walt’s strategy designed for the 21st century.

Taking lessons from Disney and A24's taste focus is instructive in what does well in company building and funding. There is a zeitgeist in company building. When you look at companies that capture "the moment," they so often revolve around a particular cultural vein. Sure, things like crypto has its ups and downs often in line with gambling culture, or COVID-inspired teleconference startups were never long for this world. But take the current AI boom. It awoke something in people not because they're fascinated by the sophistication of the transformer architecture; it was because the capability of ChatGPT made them feel something.

There are lots of defense companies, but Anduril captures the zeitgeist of Western values.

There are a lot of finance software companies, but Ramp captures the zeitgeist of commitment to quality.

There are a lot of design software companies, but Canva captures the zeitgeist of the democratization of creation.

There are a lot of workforce management companies, but Deel captures the zeitgeist of a global workforce.

Building good often means building alongside a cultural vein.

Defining Auteurs

I remember in 2005 watching Batman Begins and thinking, "this is not what I was expecting from a Batman movie." Even as a kid, it felt different to me. Unique. Almost intimidating. I remember finding myself reading the Wikipedia page for the movie, which led me to reading up on Christopher Nolan, and that was where I stumbled on the word "auteur."

Often, not really deliberately, I've been attracted to people that fit that bill. People like Quentin Tarantino, the Coen Brothers, or Martin Scorsese. Artists that truly embody the concept of becoming the "author" of their films.

Even Steven Spielberg, as generational of a talent as he is, doesn't always fit this description. I remember being frustrated by Spielberg's treatment of Ready Player One as a "popcorn movie." I loved the book and thought, in the hands of someone who treated the source material with a certain authorship, the film could have been generational vs. largely forgettable.

Wikipedia has always been my go-to for movie information, more so than IMDB, because I'm as interested in the context as I am the details. I want to read the stories about how movies are created. And I often found myself loving it when I saw movies where the same person played 2-3 or more roles at the top of the page. Director, writer, producer, actor, editor, etc. People who own so much of a creative experience.

Once again, Mario illustrates how A24 embodies this emphasis on finding and backing these types of artists. He tells a great story about how A24 came to distribute the 2016 film, "Swiss Army Man, the debut of directing duo Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert."

"While major studios were scared off by a movie about a farting corpse (played by Harry Potter), A24 knew that would be exactly what their core audience – terminally online, culturally-adventurous millennials – would love to watch."

While Swiss Army Man was a modest success, grossing $5.8M against a $3M budget, it laid a particularly important foundation for A24. Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (known as “the Daniels”) would go on to write and direct 2022's Everything Everywhere All At Once. That movie would win seven Oscars and gross more than $140M globally on just a $25M budget. Mario explained it this way:

"As a former studio executive remarked, 'You get to an Everything Everywhere All at Once because A24 nurtured the Daniels.' Rather than looking to underwrite safe bets, founders David Fenkel and Daniel Katz look for true auteurs – then back them to the hilt. While other distributors and producers often tried to subdue directors’ stranger creative instincts, A24 took the opposite approach, leaning in. 'Every project they do is ride or die,' one streaming executive said of A24. 'And they make creators feel that way. It’s their superpower.'"

In the world of building good companies, there is a direct and obvious parallel. I've always thought to myself about backing a management team, "if I could call anyone in the world about a particular topic, is this who I would call?" And there's some nuance to that perspective. Because if you were backing a space company, wouldn't you want to call the Administrator of NASA? But if you'd done that with SpaceX in 2002, Sean O'Keefe probably would have told you SpaceX was a terrible idea.

In learning from the auteur mentality, it is less about finding the most qualified person, and more about finding the most passionate person. Were the Daniels or Spielberg more qualified to make Everything Everywhere All At Once? But who was more passionate? Going back to the example of Ready Player One, it would have been a better outcome in the hands of someone less qualified, but more passionate.

I think often about the story in 2006 when Yahoo offered to buy Facebook for $1 billion. In considering taking the deal, Zuckerberg reportedly said "he wouldn't know what he'd do with the money — and that if he accepted, he'd probably just create another social-media platform similar to Facebook." Zuck might not have been the most qualified social media exec at the time, but he sure was the most passionate about building the thing into what he envisioned for it. He was "the author" of Facebook.

The Talent: Thriving or Throttled?

I'll touch on this one briefly because this is a whole other piece I've also wanted to write about unions. But when you look at things like the SAG-AFTRA strike in 2023 that shook the TV and film industries, you see a largely under appreciated labor pool. Or other reports that highlight a "crisis" in the working conditions in the visual effects industry.

You're seeing the same thing as interest in unionization in tech starts to pick up.

Building big has often left labor in the lurch because the model is focused on pushing fast, hard, and big, often with a mentality of extraction. How do we extract as much value for as little as possible?

From creating good movies to building good companies a reverential respect for the people who build the things is critical. One recent example of the pursuit of big sacrificing good is the visual effects on Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania. For those of you who haven't seen it, I'll summarize in saying... it's garbage.

Everything was there. An interesting story, access to what was meant to be the introduction of the big bad, and the quintessential Paul Rudd. But you can't create good outputs if your only motivator in determining the inputs is "make it big."

Profitable Swings

Finally, I'll end with something that is a definitive part of A24's strategy. Mario explains it this way:

"When it comes to investing in a project, A24 makes purposefully small investments. It does so to spread the risk around and ensure that a couple of bad bets don’t jeopardize the viability of the enterprise itself. This was particularly important in the firm’s early days when it operated with a more constrained budget, though it remains true today. “We specifically size films so that they’re not massive swings,” one executive remarked."

You can see it as A24 has continued to make exceptionally profitable movies, almost all of which achieve critical success as well.

This is often the art of making good movies. Not even just making a movie as cheap as possible. And not even the magic of "creativity loves constraints." But its just about allocating deliberate resources.

Look at, for example, the contrast between Batman vs. Superman and Deadpool and Wolverine. Both films are big amalgamations of IP, the combination of two beloved characters, and a LOT of expectations.

Batman vs. Superman had a $325M budget, has been out for 8 years, and has made $874M with a 29% Rotten Tomatoes score.

Deadpool and Wolverine had a $200M budget, has been out for 19 days, and has made $924M with a 78% Rotten Tomatoes score.

Bigger does not mean better. But good does not mean small.

Side note: Ryan Reynolds, Rhett Reese, Paul Wernick have absolutely acted the role of auteurs when it comes to Deadpool as a character. And Ryan Reynolds is a real auteur in everything that he does, from film to business. Mad respect.

Big AND Good

I'll repeat the line cause its the whole crux of what I'm saying:

Bigger does not mean better. But good does not mean small.

Some think it might be a bifurcation between those who have scale and those who have taste. But increasingly the winners will be those that have both scale and taste. Once again, Mario does a great job of illustrating how this is true with A24:

"Greta Gerwig’s Barbie has grossed over $1.4 billion. It is just the fourteenth film in history to do so and the highest-grossing film helmed by a woman. Though the movie was neither produced nor distributed by A24, it’s a vindication of the studio’s model. On one level, Barbie is a glossy, hot-pink commercial for a doll. More fundamentally, though, it’s the expression of a unique artistic vision, a genuinely auteur-driven film. Without Gerwig’s humor, knowing wink, and subversion, Barbie would never have become a megahit. In less inspired hands, it would be an anodyne flop, a shameless corporate cash grab, another indication of Hollywood’s creative bankruptcy."

Movies like Barbie represent what seems to me like the future of Hollywood. An "auteur-driven" love letter to a particular story. And some of those may be classic A24 profitable movies, not as big of outcomes, but quite profitable. While others can still be well-told stories that are supercharged by familiar IP. Mario makes this point as well:

"Increasingly, other studios and big IP holders are realizing what A24 has recognized all along: there is no substitute for true artistry, for a real sense of voice. The last decade of sterilized superhero fare has made this even more apparent and left audiences ever keener for something that feels different. It is now almost passé to play it straight, as shown by Amazon’s superhero show The Boys, Todd Phillips’ Joker, or Gerwig’s Barbie."

The same is true in company building. Can you build small, but profitable companies? Absolutely. I've referenced Indie Startups before.

Can you build big, soulless, monolithic companies that are optimized for pure profit motive, whether through hype or holy wars? Sure. WeWork was a thing. I'll never stop loving Matt Levine's summary of Adam Neumann's business model:

"Adam Neumann really did figure out how to make money. He figured out maybe the best and funniest way anyone has ever made money in the history of capitalism, which is "act crazy around Masayoshi Son until money spews out of him." Figuring out how to rent out office space for more than you pay for it has absolutely nothing to do with it."

And Neumann's at it again. We'll wait and see how it turns out.

But the real question is can you build meaningful companies around cultural movements headed by visionary auteurs and still drive outsized returns and impact? I think yes. But they're harder to build than they are to throw money at. So the industry can't just devolve into the hits business. We have to find room to build these unique gems. Empower these unique auteurs. But make no mistake; they're out there.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Really enjoyed this piece reminded me a lot about Jim Collins "Good to great".

That analogy really works. I loved Mario's piece on A24 so great to revisit it.

to make the comparison fully apt, box office for a movie would be reported over a 10-12 year period, during which a bunch of qualitative/quantitative indicators could be used to claim success, and the movie producers would rake in the dollars regardless.