This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Before the Linkedin haters come after me, the title is a joke. It made me chuckle. And for those of you that love Linkedin (and B2B sales) unfortunately for you, the subtitle of this piece is a lot more the point than the title is.

Also. Fair warning: I'm going to spoil the crap out of the 1939 Wizard of Oz movie, the 1995 book Wicked, the 2003 musical of Wicked, the 2024 movie of Wicked, and (tangentially) the 1950 Japanese classic Rashomon.

Alright. Now, on to the main event.

I've said it before (and over and over and over again), but I'll say it again. Movies are my thing. My jam. I love stories. I love narrative. And, more than anything, I love when stories keep going. I remember reading some quote from Christopher Nolan when he was making the Christian Bale Batman movies where he said, "Movies aren't like comic books. They aren't meant to go on forever." And then Marvel (to their detriment) responded by saying, "Hold my beer."

I, like many MCU fans, have been disappointed by almost everything they've made since Endgame. But that's not because its too much of the stories I love. It's that the stories aren't good. I would be more than happy to have a new Marvel release every month if the story was good.

L. Frank Baum, the author of the original Wonderful Wizard of Oz novel in 1900, had the same attitude. Fun fact, he wrote 14 Oz books over the course of 20 years! Are they good? I'm not sure. I haven't read any of them. But I respect his vibe. When I was a kid, we had a children's book adaptation of the 1985 movie sequel to The Wizard of Oz, called Return to Oz. The cover art alone left an impression.

That's how I knew the Wonderful World of Oz was weirder and more extensive than I would have thought beyond just the original movie. That weirdness is, perhaps, what primed my intrigue when I was in my early pre-teen years and I started seeing these other books in bookstores that seemed connected to that Wonderfully Weird World.

Given some of the books more racy scenes, I'm not sure why my family owned Wicked, nor why I was allowed to read it as an 11 or 12 year old. But it has stuck with me ever since. This unusual story revolving around usual characters. The hints of an unknown narrative being grounded in what felt known.

I saw Wicked the musical for the first time in London in 2008 and then again on Broadway in 2013. And I remember walking away from the musical thinking, "that's not how the book was at all." I can't say that I dug into the weeds when I saw the musical, I just kind of reflected on it and then went on my way.

But the release of the 2024 movie has let me reflect back on it and return to a concept that, although Wicked was probably one of my first introductions to the practice, it's something I think about often. The concept? Revisionist history. And the more I've thought about it, the more I've realized that it plays a key role in storytelling. Because any good storyteller is capable of making a story moldable; something that can be retold, reframed, and reused.

Revisionist History

In preparation for Wicked, the movie, coming out this year, I re-read the novel. But beyond just revisiting the story, I wanted to unpack the motivations behind Gregory Maguire's repackaging of a beloved story, especially his focus on one of the most one-dimensional, iconically evil villains in cinema: The Wicked Witch of The West.

In the early 90s, Maguire talks about his desire to explore the nature of evil and how even what we name "evil" and refer to as "wicked" can be a self-fulfilling prophecy:

"If everyone was always calling you a bad name, how much of that would you internalize? How much of that would you say, all right, go ahead, I'll be everything that you call me because I have no capacity to change your minds anyway so why bother. By whose standards should I live?"

Margaret Hamilton's 1939 portrayal of the Wicked Witch of The West feels like it doesn't contain a lot of nuance. She has basically no redeeming qualities. She's just a caricature of what should scare you.

But Maguire wove a story that is so much more complex than that. The novel is a much more subtle journey of a character who is misunderstood and frustrated. The musical is an even less subtle exploration of someone who has clearly articulated goals and runs into the most meaningful obstacles to becoming what she wants to be.

The 1995 novel is a revisionist history of the original 1900 novel and 1939 movie. In turn, the 2003 musical is a revisionist history of the 1995 novel and the 2024 film is a slight revisionist history of the 2003 musical. The 1900 / 1939 iterations portrayed evil. The 1995 novel explored evil as a narrative. The 2003 musical unmasked evil as an emotion. And the 2024 film presented evil as a matter of perspective.

In the 1995 novel, the character of The Wicked Witch is a very gradual creation. Elphaba, the main character, sorts of adopts it with a smirk. People want to think she's wicked? Let them. Maybe they'll leave her alone.

In the 2003 musical and 2024 film, its much more deliberate. There is an exceptional song that represents a perfect foreshadow of what's to come: The Wizard and I. In it, Elphaba talks about how meeting the Wizard has been something she's always wanted:

When I meet the Wizard

Once I prove my worth

And then I meet the Wizard

What I've waited for since, since birth

And with all his Wizard wisdom

By my looks, he won't be blinded

Do you think the Wizard is dumb?

Or like Munchkins so small-minded? No.

Meeting the Wizard, working with him, achieving what she's always wanted, she sees a vision of what that could lead to:

But I swear, someday there'll be

A celebration throughout OZ

That's all to do with me!

And she's right. From the very beginning of the story, we know that all of Oz would celebrate in her name, but in honor of her death. And what she's wanted her whole life ultimately becomes her undoing. After meeting the Wizard, she asks for his help in supporting Animals who can talk and have souls. But he's not only indifferent, but incriminates himself immediately. He's the perpetrator of, effectively, a genocide against thinking, talking Animals.

Later, in Defying Gravity, Glinda says she should just apologize to the Wizard and she can still have what she's always wanted. Elphaba's response is as honorable as it can get:

"But I don't want it. No, I can't want it anymore."

So how does the Wizard and his ilk respond? An immediate Oz-wide announcement warning everyone of the Wicked Witch that can't be trusted or believed. A character formulated in 1900, and given a face in 1939 was given a seed of humanity in 1995 that exploded into an emotional journey in 2003 and exposed for the propaganda that it is in 2024.

A one dimensional caricature becomes an impactful emotional character through the power of storytelling. An exploration of evil, an introduction of relationships, and a few killer Broadway songs, and you have a story that is transformed to powerful effect.

The key takeaway lesson from this story evolution is the power of one key exploratory phrase: "what if?"

What If...

Revisionist history is best crafted by asking the question "What if?" Famous examples like The Man in The High Castle or 11/22/63 ask the questions "What if the Nazis won?" and "What if you tried to stop the assassination of JFK?" respectively. Those two feel like some of people’s very favorite “what if” questions.

I thought I had written about this before, but I couldn't find a mention of it. In middle school, I remember randomly stumbling on a book called "The Never War." It was one entry in the broader Pendragon series where a boy named Bobby Pendragon travels through space and time to complete certain missions. In that book, he finds himself in 1937, not long before the Hindenberg disaster. At first, he thinks his mission is to prevent the crash.

At one point in the story, Bobby is able to travel forward in time to the 51st century in the year 5010, and visit the New York Public Library. He gets access to a super computer that has "every bit of information that exists," and is "12 billion times more powerful" than the computers that existed in 2003 when the book was written.

Re-reading this section of the book, I wondered what the estimate would be for today just 20 years later vs. 3,000 years later. When you compare Earth Simulator (NEC) in 2003 vs. Frontier (Oak Ridge National Laboratory), its about 33 million times more powerful. So this future super computer is pretty robust.

The librarian with the super computer explains that because the computer is so powerful, you can treat every event as a massively complex mathematical equation. As complex as it is, change even one variable? And you change the whole outcome. The calculus of "What If". They use the computer to determine the "What If" future of if they prevent the Hindenberg crash. The results were pretty surprising, with the librarian telling them it took all of this massive computers resources to calculate:

"We saw Washington D.C. hit by an atomic bomb. New York got slammed too. London was history. If the Hindenberg arrives safely, then (through a chain reaction of events) Germany will be the first to develop an atomic bomb. We saw a view of New York City. There were people waiting in line for food. Children slept in the streets, cold and hungry. Tents were set up where the roads had been. Thousands upon thousands of people lived in the rubble like rats. But this wasn't right after the bomb. This is a view of New York City on Third Earth, over three thousand years later."

Stories like Wicked, like Pendragon, they captured a key aspect of storytelling. Knowing how stories can be rearranged, whether its fiction or reality that you're rearranging.

One of the best examples of "What If" storytelling I've been exposed to recently is actually something I wouldn't have watched if it wasn't for this blog! Back in August I wrote a piece called Science Fiction's Dueling Fates and one of the comments turned me onto a TV show that perfectly encapsulated "What If" storytelling.

For All Mankind

After getting this recommendation, I consumed the first 4 seasons of For All Mankind in about 1.5 weeks (granted it was right after our baby was born, so I had a lot of sitting around time.) And the show is a perfect example of "What If" storytelling. "What if the Russians beat us to the moon in the 60s?"

From there, everything is a trickle effect. The space race never stops, we colonize the moon, we unlock nuclear power, we get to Mars. Electric cars are common in the 80s. The oil and gas industry is demolished. On and on.

That show is an exceptional example of what I've written about before as Solution Science Fiction. People ask the question of why we should explore space when we have problems at home, but the show demonstrates the solutions. The more we're tackling the scientific frontier, the more technological progress we make.

For me, there are three key takeaways from revisionist history:

(1) It's fun! It is SO much fun to rewrite stories. Whether its fiction or reality. For example, Marvel literally has a TV show called "What if?" where they explore alternate realities in the Marvel universe, and it's lethargic. There are so many stories that the MCU did tell that I hated, so getting to see a different flavor is nice. In fact, it's so much fun that I've got a 10,000 word google doc with ideas for Indiana Jones fan fiction I want to write called The Jones Diaries, much of which would be revisionist history.

(2) It's an exceptional approach to science fiction! Like I said about For All Mankind, looking at what could happen is how I wish we would write more science fiction. I never resonate as much with the other-worldly sci-fi "in a galaxy far, far away." I want sci-fi that has one foot anchored in our reality. Even if its thousands of years in the future, things like the Foundation series or The Expanse or Red Rising. But also, I think more people could use the "What if" paradigm right now to write near-future science fiction about solving climate change, colonizing the galaxy, curing cancer, or any other technical challenge that, today, feels like a hopeful dream at best, far from reality.

(3) It's a critical aspect for framing any pitch, whether as a founder or an investor! This is the one I want to end on. When people talk about pitching, whether its for funding, hiring, partnerships, or customers, they're talking about storytelling. More founders, investors, and operators would be better suited if they studied storytelling. And what revisionist history teaches us about storytelling is that Perspective is a key character.

Perspective: A Key Character in Every Story

I've written before about how long before I wanted to get into startups, I had wanted to go to Hollywood. My original major in college was Film. And like any good film major, I've watched a lot of Akira Kurosawa movies. The great auteur.

One of his most famous films is Rashomon, and it is a perfect example of framing Perspective as a key character in your story. In the movie, several people tell their own version of the story of how a samurai was murdered in a forest. Each person's retelling is changed to try and frame themselves in the best light.

That movie is the quintessential example of how Perspective is a character in any story. Knowing your audience, knowing their bias', knowing their perspective. Any good story is capable of evolving to encapsulate different people's perspective at different times.

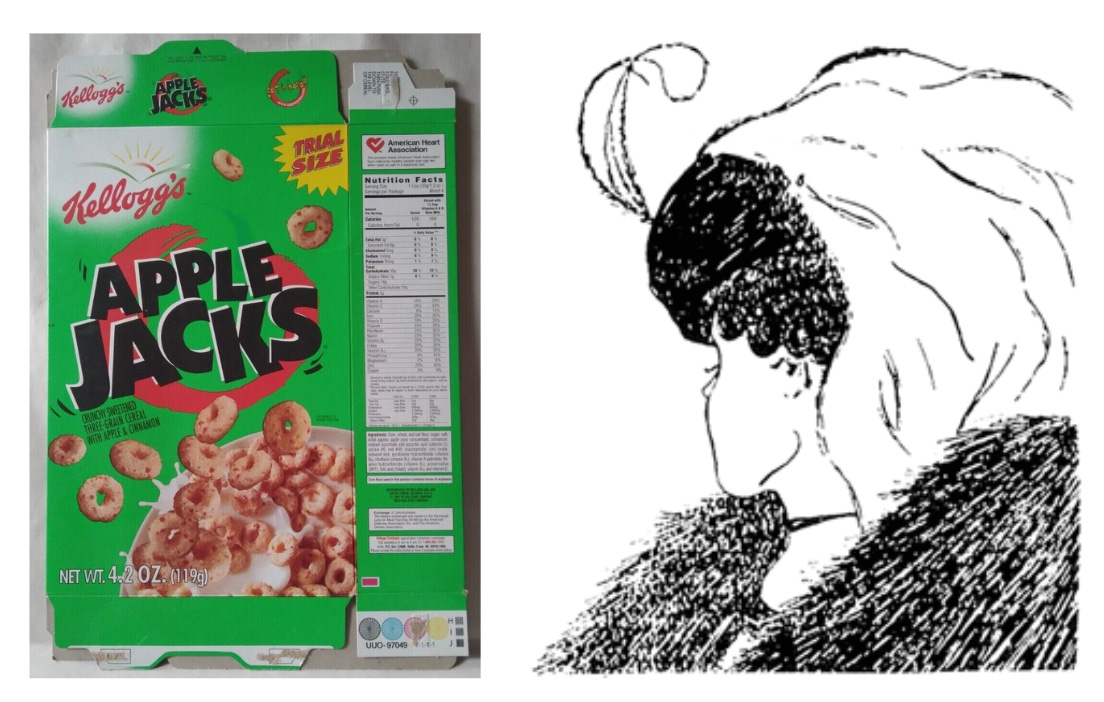

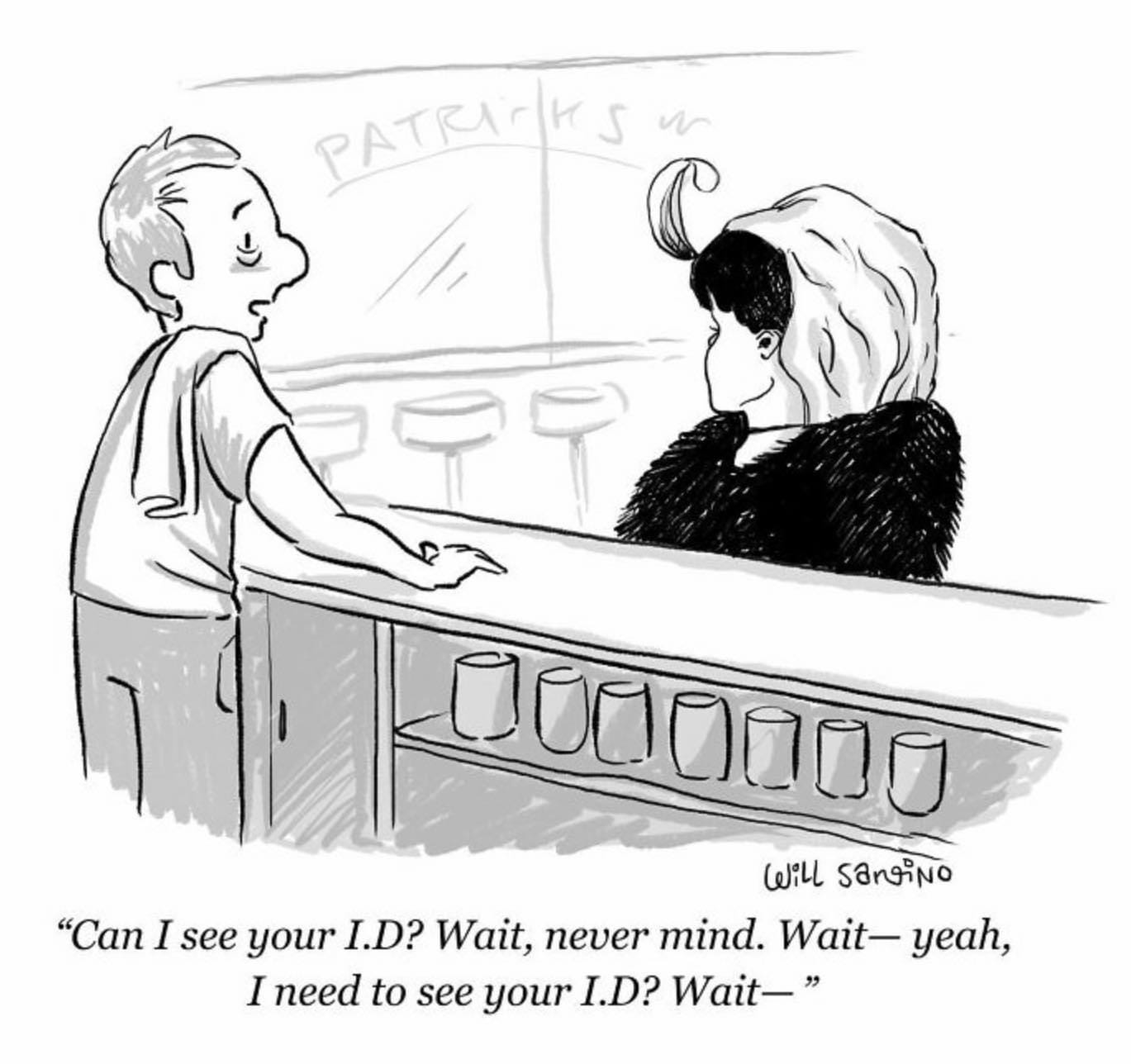

Thinking about this reminded me of the Apple Jacks boxes of my youth. I couldn't find a picture of the actual back, but they used to always have optical illusions. The one I remember the most was this one.

Is it an attractive woman with her head turned to the side? Or an older woman with a large nose? Side note, this cartoon made me laugh.

Your perspective matters. What you think it is, what you want it to be, what you wish it wasn't.

A lot of times, tech companies get ragged on for being boring. Developer tools, backend infrastructure, etc. etc. But it makes me think of a collection of things.

First? As Palmer Luckey explains, "You don't need to care what everyone thinks. You need to care about that 1% of the world that is going to be your ride or die." So don't care what anyone says. Tell a story that a specific group of people or type of person will resonate with.

Second? Every good product addresses a "job-to-be-done." And if someone wants a job done its because they can envision a world that doesn't currently exist. And if your product can help make that world a reality, then critics be damned. Build for the world that audience wants to exist.

Finally? We need better storytellers. You need to get better at finding stories that are worth telling. Worth believing in. Whether its the company you want to build, or work for, or invest in, or even compete with. Everyone needs a good villain. Companies like Anduril exist not just because of the company they want to build, but specifically because they want to take on existing defense primes.

So get out there and revise history. The future may depend on it.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

This has to be my favourite piece so far. Thank you for writing it