Science Fiction's Dueling Fates

Painting Two Dramatically Different Worlds in Our Collective Imaginations

This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Quick Announcement: Contrary Research is hiring for a Research Analyst. To apply, reach out to research@contrary.com. Alright, on with the show!

I have been coming back to science fiction more and more lately. I first really dug into my thinking in one of my favorite (though not most popular) pieces, Historical Futurism in July 2023. I laid out how I saw the way dreaming about the future shaped the way we lived today. Next, in Life Imitates Art in April 2024, I reacted to a new sci-fi movie trailer that had bothered me for a movie called Atlas. The movie hadn't come out yet, but my expectations were pretty much met when it did.

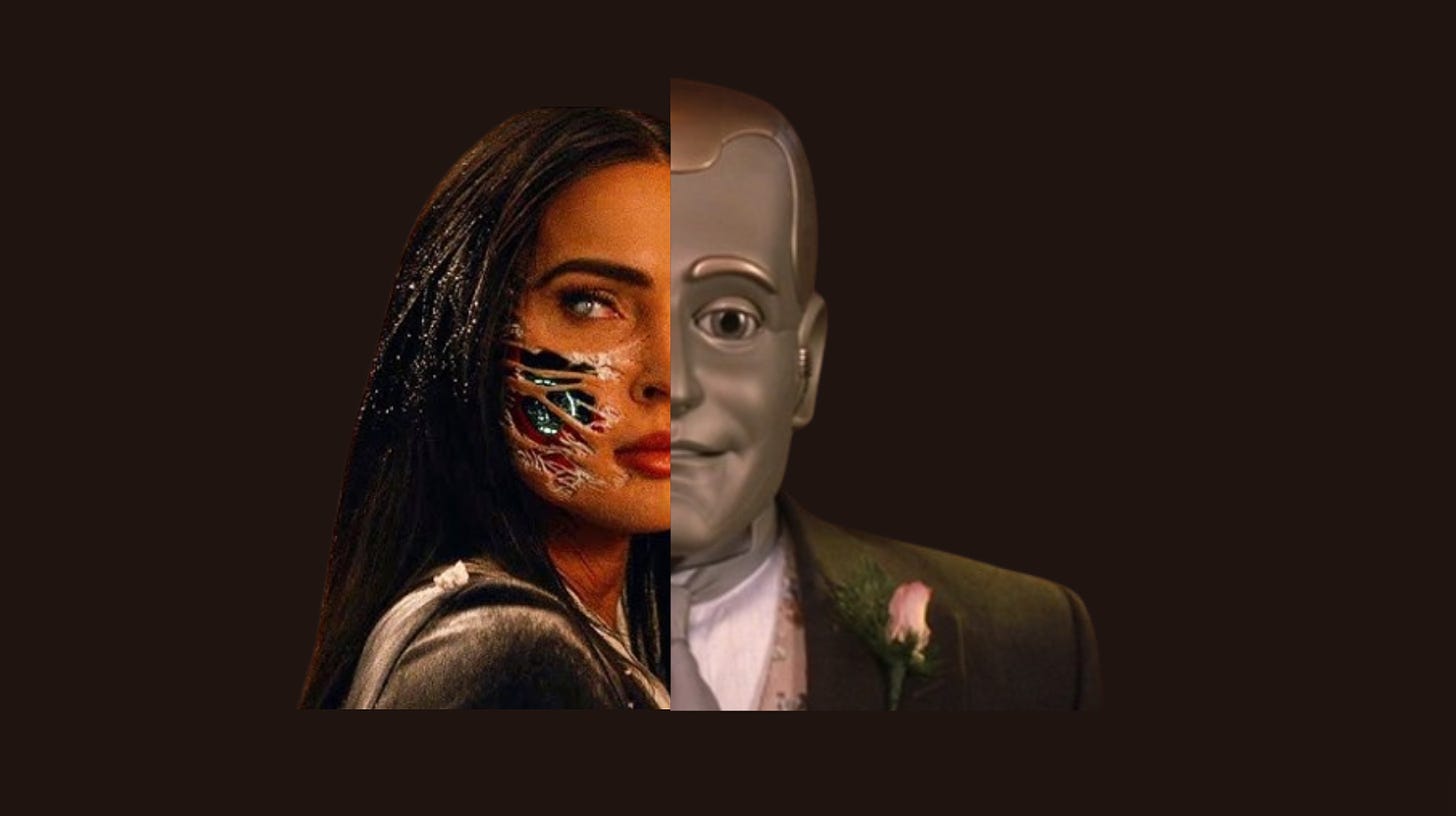

Today, I'm back at it again. I recently noticed a sci-fi trailer for a movie called Subservience. As I was watching it, I realized the plot was very similar to a movie from 1999 that I really like; Bicentennial Man. Both start with a family being intrigued by a lifelike new robot that can help around the house. But that's about where the vibes take a dramatic shift.

Bicentennial Man wasn't a huge hit by any means, but I've thought about it often as a really interesting exploration of humanity, slavery, prejudice, intellectual freedom, conformity, love, mortality and immortality. It makes me think, which is enough for a movie to stick in my head for a long time.

The plot of Subservience, as far as I can tell, sounds like what an annoying teenager would come up with while high:

"They're like servant robots, but what if they were hot? Like Megan Fox hot? But then, like, the husband falls in love with the robot, cause the wife is sick or whatever, but then the wife gets better I guess, and then like the robot tries to kill the wife cause she's jelly?"

*Rubs eyes*

This stark juxtaposition of these two movies taking a similar concept in very different directions had me reflecting again on just how dramatically science fiction has changed over the last 25 years. And, in particular, what that means for the people who are collectively trying to dream up the future in what they're building.

The Rise of Dystopia

I've written before about the rise of dystopian fiction:

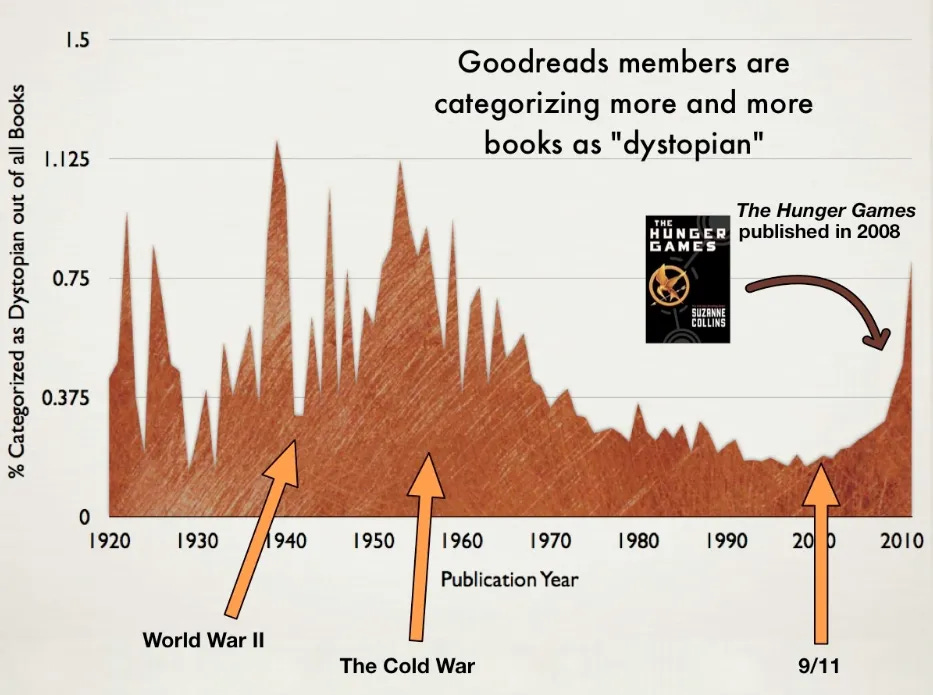

"We're no strangers to dystopian nightmares in our literature. During World War II and the Cold War, there was a fertile ground for dystopian storytelling. But from the 80s to the early 2000s, we took a break from nightmares and lived a pretty good life. Then, things started to change."

I think about this chart all the time. Where we had been slowly recovering fiction from the grips of the dystopian boom during WWII and the Cold War, it suddenly shot back up. This chart correlates the rise to 9/11, and maybe that's the case. In 2016, after Donald Trump's election, books like 1984, Brave New World, It Can't Happen Here, and The Handmaid's Tale all topped the charts.

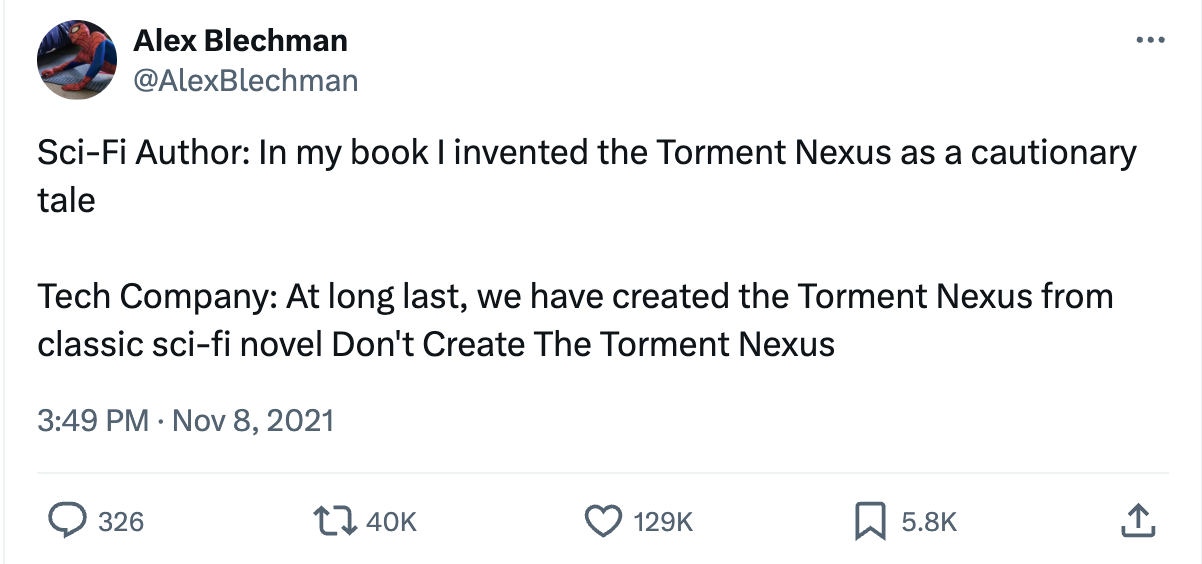

But whatever the drivers, there has been a myopic obsession with dystopian futures, with seemingly little thought given to how much this impacts the way people view their reality. Fiction and media does so much to shape people's lived experiences.

Just a small example, I was thinking recently about Kate Bush's song Running Up That Hill. I'm no hipster, so I won't tell you I was familiar with the song from 1985 before I was exposed to it in Stranger Things Season 4. But the nearly 40-year old song's inclusion in a popular show saw streaming of the song shoot up 9,000%. When the song first came out it peaked at 30 on the Billboard Hot 100, but after the Stranger Things bump, it got up to 8.

The power of music and books and movies and TV shows lies in the fact that they don’t just take up our eyeballs and time. They impact how we live our lives, the decisions that we make, and how we see the world around us. And, while dystopian fiction can act as a wake up call, it can also be a dangerous drug in a world increasingly in the grips of hopelessness and depression. The collective imagination is increasingly becoming a collective nightmare.

Dreaming The Dream Nightmare

In a piece that really wasn't about science fiction, I touched on a point that I think is relevant here. One of the biggest drivers of hopelessness, in my opinion, is the complexity of different people playing different games that leave many to feel like they can't win the games they're playing. In Playing Different (Stupider) Games, I made this point:

"One of the biggest obstacles to most of the systems in the world, whether its healthcare, criminal justice, mental health, housing, or capitalism itself—all of them are filled with people playing different games.

My kids are vaccinated. We got the COVID vaccine. I don't hate vaccines. But honestly, I understand where the conspiracy theories come from when it comes to healthcare. Something feels off because you start to feel the sneaking suspicion of someone else's profit motive. In Jim Carrey's infamous CNN discussion on autism and vaccines, he said it pretty clearly:

'I don't think we can afford to assume that the people who are charged with our public health any longer have our best interest at heart all the time.'

I don't believe that conspiracy theory. But the same skepticism of the healthcare complex, the military complex, the prison industrial complex, all of these things are based on the skepticisms derived from other people's profit motives. In other words? People feel like they've been playing stupider games."

What I referred to in that piece as "playing stupider games" was "not realizing that you're competing with someone who is playing a very different game."

You hear about things like incarceration rates. The US has "5% of the world's population while having 20% of the world's incarcerated persons. China, with more than four times more inhabitants, has fewer persons in prison." Then you learn about the prison lobby. Companies like CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America) alone generated $1.9 BILLION in revenue from private prisons.

You start to feel hopeless because everything, from guns to climate change to healthcare to prisons, are dripping with somebody else's profit motive. How do you change anything when there are companies making billions of dollars off of things not changing?

One response that fiction has to this dilemma is to simply shut it down. Spoiler alerts:

Escape From L.A. has Snake Plissken triggering a super weapon, "deactivating all technology on Earth" to avoid unjust domination.

Fight Club (at least the movie version) ends with the execution of Project Mayhem; erasing debt records by blowing up the headquarters of credit-card companies.

V For Vendetta concludes with the destruction of the British authoritarian state by blowing up Parliament.

Mr. Robot takes a page out of the Fight Club manual and works to encrypt all user data for Evil Corp. to erase all consumer debt.

Hopeless situation? Meet the scorched earth solution.

That's one way to play it. But there's just got to be a better way, right? Most dystopian fiction just paints the picture and says "don't be like this." Then there are these scorched earth solutions that just burn it to the ground.

But... where are the solutions?

The fun thing about fiction is that it is literally boundless. You can do anything. You can make anything happen. Your only boundary is your imagination.

Often, fiction will kick up against cries for believability. But guess what? Sentient alien robots that turn into semi-trucks and genetically-engineered reincarnated dinosaurs aren't particularly believable either, but those movies made a BILLION DOLLARS.

So where is the Solution Sci-Fi? Climate change is a huge problem. Imagine the solution. Death before your time is a villainous tide that could be stemmed. Imagine the solution. Resources are finite and need replenishing. Imagine the solution.

Calling For Solution Sci-Fi

I talked last week about loving auteur-driven movies where you see their name show up in 3-4 roles for the film. Unfortunately for Dean Devlin, who wrote, directed, and produced the 2017 film Geostorm, those movies don't always do well.

I remember seeing the trailer for this movie in 2017. Right off the bat it starts out with some pretty heavy-handed exposition: "Thanks to a system of satellites, we can control our weather." From there it devolves into a hellish climate change-esque version of Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs.

It was, in the words of the film's Wikipedia page, "lambasted" by critics. One critic called it "big, dumb, and boring."

Now, I've never actually seen the movie. But the trailer stuck with me because I remember thinking as it started, "huh... could we use satellites to control the weather?" But then the rest of the trailer proves its just another disaster-porn explosion-fest and you think "whatever" and move on with your life.

Then, a few years later, I came across Rainmaker, a cloud seeding startup founded by a 24-year old college dropout that is using technology to make it rain. That's the kind of thing that, when Augustus Doricko was a junior in high school, could have been inspired by an awesome Solution Sci-Fi movie about controlling the weather. Instead, its a trashy forgotten movie, and Doricko was inspired by something else, luckily.

Where's the fiction that is taking practical reality and using that to solve actual problems? "We can't solve XYZ problem because we don't have the money." Can't we at least start by dreaming the solution? And granted, we've been inspired by plenty of science fiction. But not always the best versions of it.

But what about solving actual problems? I read two books this year that represent versions of realistic fiction, though both acting more as cautionary tales, are Nuclear War: a Scenario and 2034: A Novel of the Next World War. Both are super interesting fictional representations of real world environments; both attached to global conflict.

Take 2034 for example. As a review for the book, Jim Mattis, previously the Secretary of Defense, said “War with China is the most dangerous scenario facing us and the world,” and said that the book “presents a realistic series of miscalculations leading to the worst consequences. A sobering, cautionary tale for our time.” Taking that realistic approach to shaping a story is powerful. It certainly makes it an even more effective cautionary tale.

But what if we were to create fiction that didn't just scare the ever-living crap out of us in increasingly realistic ways, but actually proposed a realistic solution?

Lets go back to the industrial prison complex. How do we solve that?

Funny enough, Palmer Luckey has talked about how, after leaving Oculus, he considered two other possible things to work on other than solving national security with Anduril. One of them was "solving incarceration." He explains his exploration this way:

"I wanted to basically take out the incentives of the private prison complex that exists today. Right now private prison companies are growing. There's more and more people being housed in privately operated prisons. They're publicly traded, and those companies have a strong incentive to lobby for and perpetuate laws that incarcerate people for the longest period of time for the least serious crime.

In other words, they don't want murderers and terrorists. they want non-violent drug offenders who will be in prison for a long time, and when they get out of prison they want them to come back and be a repeat customer. They want good good tenants. They want good occupancy, good tenants, and the incentives they've set up with the government where the government pre-pays for these beds, the government basically says 'well, we've already paid for the bed so if they're not full then we're not locking up enough people.' It's a very bad set of incentives.

So, my idea was that I could start a private prison company that would run as a non-profit organization and we would use the tax advantages of that to out-compete private prison companies. And more importantly we would have a business model that would incent everybody towards the right set of incentives. So what I wanted to do is go to the government and say 'listen, I'll lock up your prisoners but you don't get to pay us up front. In fact, you can't pay us up front. You have to pay us after the person serves their term and then stays out of prison for five years. Then you're going to pay me. And the idea is that now all of a sudden I'm motivated and my whole organization is motivated to get people through as quickly as possible, release them as quickly as possible, and then have them stay out of prison and not return to crime.

That would have been a game changer, and it would have been a very attractive business model to these governments that are always looking to delay their expenditures. The biggest problem that I ran into as I looked into this is it wasn't a technological problem. It was a lobbying and marketing and government affairs problem. And it wasn't at a federal level where you can basically convince a handful of people and then achieve success. It was going to be this locale by locale thing where you have a lot of people who depend on prisons for jobs, you have a lot of politicians who are very involved in it. And also, the deals are not re-competed very often. This isn't like enterprise software where people are always on the lookout for a way to get an edge or move to a new provider that could reduce their costs or risk. It's like 'oh yeah we're going to re-compete this deal in 35 years.' And so it would have been this thing where I just couldn't have made an impact fast enough."

Imagine a fiction series, akin to Jack Reacher, traveling from jurisdiction to jurisdiction going to war with the monied incentives behind the existing prison status quo. Give the villains that are trying to make money off of "repeat offenders" into eternalized caricatures of evil in a particular fictional antagonist. We want people like Henry Kissinger or the Murdoch's to bristle at how they're portrayed in The Trials of Henry Kissinger or Succession. When you do something for work that no one sees, you're profit-driven. When your friends and family love a show or book that portrays you as a monster? You become socially motivated.

And make it realistic. Study it out. What would it take to execute the "lobbying and marketing and government affairs" problem that Palmer saw? And don't tell me you can't make it interesting. The West Wing was one of the highest rated shows in history. Even Veep is borderline clairvoyant in its prediction of American politics. You can absolutely make boring things interesting. AND if they're accurate they can have an even more sophisticated impact on the real world.

"I Just Want Us To Be Better"

As I was pondering how to end this piece my mind kept coming back to this tweet (or... xeet?) from Mike Solana. I just want us to be amazing. I want us to be better than we are. To dream up amazing fiction to inspire an amazing reality.

I appreciate more and more seeing important people in tech criticize the lack of dreaming going on in our fiction. From Sam Altman decrying Oppenheimer's missed opportunity to inspire a generation of physicists:

To Beff Jezos acknowledging the threat posed by "doomers and their art."

We can dream up better solutions. We can spend more time leveraging fiction, with all its unfettered intellectual capabilities, to tackle the problems facing our world. I want Tolkien-level world-building. His Legendarium alone, which was just his expositional world-building resource, was 1.5 million words! More than 10% of Tolkien's writing was just to add thoughtful context to his work.

Andy Weir's The Martian is considered one of the most scientifically accurate sci-fi movies. That's a fun detail on its own. Its particularly interesting as we get closer and closer to the possibility of manned missions to mars. But what about the problems facing us right now? Where are the scientifically accurate treatments of tackling aging, disease, poverty, food shortages, energy dependence, climate change, or war?

I remember listening to a podcast where someone mentions the fact that its a shame that the best movie treatment of the reality of eventually overcoming the effects of aging is In Time with Justin Timberlake. (I have no idea where I heard that; if you have any idea, LMK). Certainly an interesting movie, but where are the hard-hitting well-researched books and movies and TV shows that try to portray potential future states as accurately as possible? Not just the problems, but the exploration of the solutions as well?

That's the fate I hope for from science fiction. Rather than the "what if Megan Fox was a hot murder-bot" variety.

But one can only dream.

___________

P.S. These explorations always end up leaving me with some interesting reading that, while I typically save for later, I don’t have time to consume / incorporate during my Saturday morning panic writing sessions. Some of the nuggets I found today were particularly interesting, so I thought I’d leave you a “further reading” section:

The Rise of Dystopian Fiction: From Soviet Dissidents to 70’s Paranoia to Murakami

Dystopian Literature: Evolution of Dystopian Literature From We to the Hunger Games

The Wikipedia entry for Fredric Jameson, the Knut Schmidt-Nielsen Professor of Comparative Literature, Professor of Romance Studies (French), and Director of the Institute for Critical Theory at Duke University.

His book, Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions

His original scholarly essay on the topic, Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

You should check out for all mankind

I strongly recommend "The Prefect" by Alastair Reynolds. The novel itself is a sci-fi detective thriller that stands on its own as a great story. The technology is integral to the story, but the plot stands strong regardless of the tech. The tech itself is a fantastic far-future imagining of Neuralink, blockchain, and AI. Written in 2007 long before the former two were around. The audiobook is narrated by John Lee whose voice I could listen to 24/7.