This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

A Tweet Heard Round My Head

It's always the sign of a great tweet when it leaves you thinking about it so much that you put off the thing you were planning on writing about and write about something totally different. Even when your baby was up until 1 AM and it's Saturday and you haven't started writing anything. You still can't bring yourself to write about anything else. That's how I felt this week after a tweet from Matthew Ball.

If you don't know who Matthew is, he's absolutely worth a follow. He's worked in media and entertainment, is one of my favorite writers on gaming, and wrote a book about the metaverse.

So what's the mind-consuming tweet in question?

The replies are fascinating. Not only because people often just whip stuff out on Twitter without thinking about it, but also because of the broad and diverse set of perspectives. By asking one question you expand across industries, into discussions of stock-based compensation, and the value of different measures of profitability.

I've seen similar discussions about different types of companies that get built (side note: if you're not following Aashay, Ho Nam, and Post Market, that's a real loss. Here's a peek.)

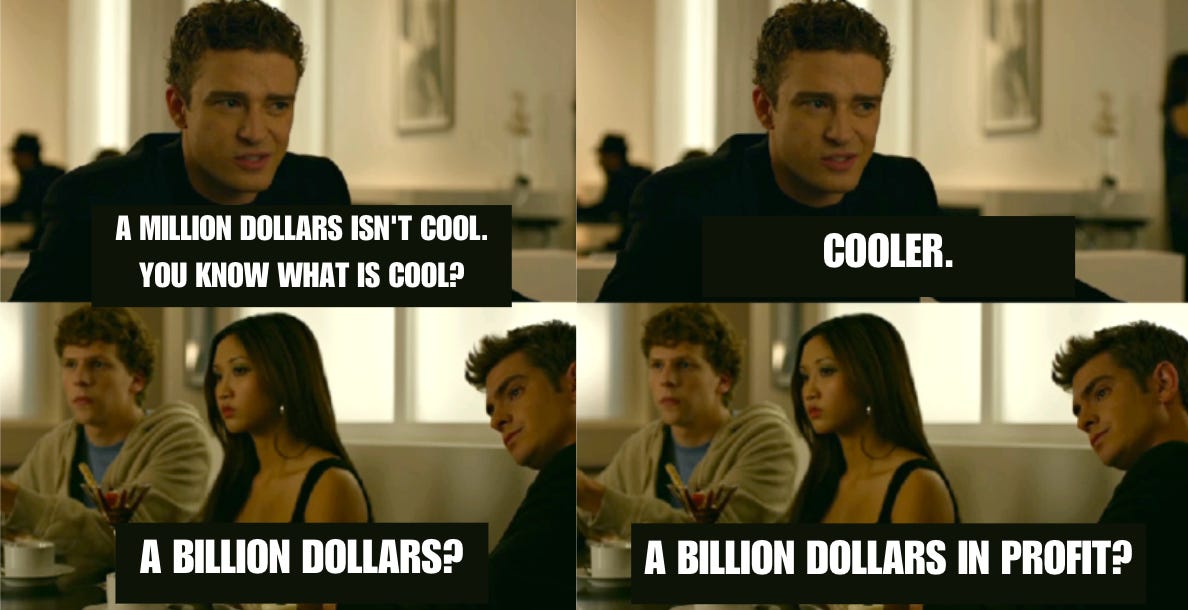

Now, I'm no public analyst. There are a lot more thoughtful in-the-weeds analysts out there than me, many of them show up in the comments on those threads. So my head wasn't just focused on answering the question. The crowd-sourced efforts from the comments has led to this follow-up list from Matthew.

More than that, it left me reflecting on the long-run outcome of the current venture ideology. So I wanted to spend a second trying to articulate my reactions, justifications, disappointments, and resolutions.

Cash Is, In Fact, King

If you've been reading my writing for a long time you might have seen this consistent thread in the background. The idea that ultimate outcomes SHOULD matter, but most investors only need to focus on ISOLATED outcomes.

My very first post when I started writing consistently, one of the first things I talked about was cycles. As you see things like the financial crisis take place, you also see a smattering of exceptional companies get built around the same time.

Matthew's time stamp of "in the last 15 years" falls about in-line with this. What companies have been funded in the US since the financial crisis that have become (1) public, (2) profitable?

I've also written a few times about the cases of excess. In one piece I talked about companies like WeWork and Lyft that have raised significant amounts of capital but in both cases are now worth less than ALL of the equity capital they raised (WeWork raised $20B and is worth <$400M!). In another piece I wrote about how some of those "stewards" of capital, like Adam Neumann at WeWork or John Foley at Peloton, have been given second bites at the apple (in Neumann's case a massive $350M bite).

For me, it all circles back to this idea of an economic engine, something else I've written about before. In the piece, I quoted Bill Gurley extensively. Here's a quote of his I think about all the time:

"While growth is quite important, and even though we are in a market where growth is in particularly high demand, growth all by itself can be misleading. Here is the problem. Growth that can never translate into long-term positive cash flow will have a negative impact on a DCF model, not a positive one. This is known as “profitless prosperity.”

Interestingly, Bill Gurley was intimately involved on the board of both Uber and WeWork. There's an entirely separate debate around being founder friendly. In the post on Adam Neumann's latest chance, I dug into some thoughts that a16z making a $350M bet on Neumann’s new company is largely a "founder-friendly" insurance check. Proving that, no matter what, they'll get behind visionary founders.

But I think there's something to be said about Uber and WeWork both being dramatic cases of excess and cash incineration. Not to mention some pretty terrible management tactics at both companies. Maybe Bill Gurley had a point with the issues he took.

Rewarding Expectations

One reaction that I had to Matthew's post is to consider what people have been rewarded for in the public markets. Markets have been rewarding growth over profit for over a decade, so just because the narrative has shifted in the last 5 quarters doesn't mean every business can turn on a dime. Matthew made a fair point in response though:

"I don't think it's unfair to ask that profit >$0 when the filter is basically all companies founded in the last 15 years in the largest economy in the world. It's true some businesses are harder than others, but the question isn't "give me dozens of such examples", it's just a few or even one, and so the average shouldn't really matter."

But when I reflect on the reality that every company faced, they were all operating in the same "largest" economy, but that means they were also captivated by the same game. Growth is what got rewarded in public markets.

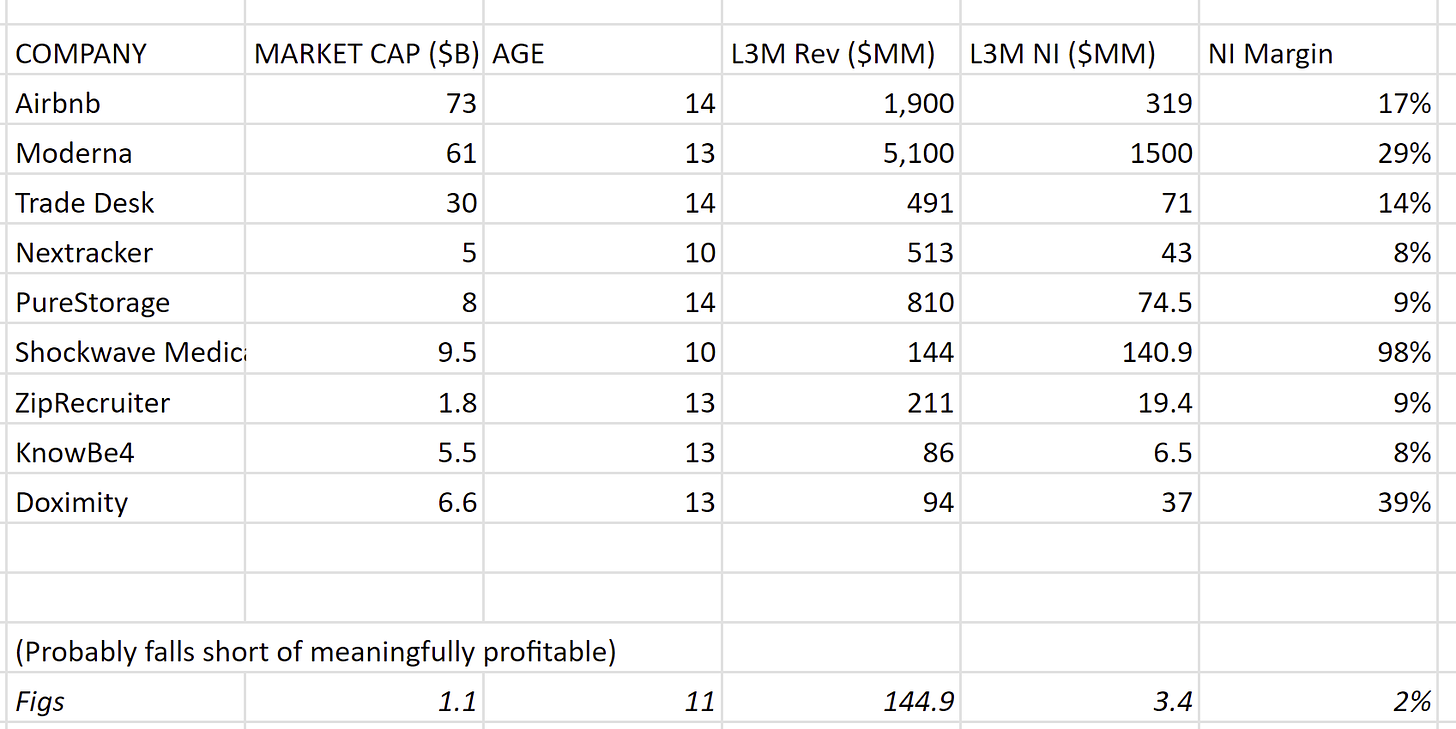

When you look at charts like this, you see that correction very clearly. The companies that saw the least painful stock price corrections were those that were both profitable and still fairly high-growth.

Before 2022, you saw a clear statistical correlation between growth and valuation multiples. Today, you see a clear statistical correlation between balanced profitability (e.g. rule of 40) and valuation multiples.

The idea of "playing the game on the field" is the reason I'm not that surprised there aren't more profitable companies around today. Even examples like Amazon, who took longer to generate profit, still did it in less than 15 years. And individual business lines, like AWS, were profitable within ~11 years, generating $4.3B in net income after 15 years. The game for the last 15 years (e.g. the environment the majority of these companies have grown up in) has not prioritized profit in any meaningful way.

But venture investors so often talk about their focus on building generational companies; surely they would want the businesses they help fund to add to that list. Certainly, those companies should drive the most returns, right? So if VCs entire business model is driven by returns, why would they allow this lack of profit to occur? It goes back to this key point:

Ultimate outcomes SHOULD matter.

But most investors only need to focus on ISOLATED outcomes.

A Long Game? Or A Long Con?

Before I get into a bit of a spicy take, I want to start with a caveat. There is the ideal world that many of us aspire to (only the hucksters prefer the case for every company and investor being a sucker). Most people want to invest in exceptional companies that are responsibly built, that provide meaningful value, do little harm, and generate extraordinary returns. I want to invest in companies that drive the most value in every sense of the word. But that aspirational case is not always reality. There are a lot of not-great dynamics at play in the world of company building and funding.

I got into a debate with a friend of mine recently about how venture is all just a waiting game. "Invest in the best companies, and just leave them alone to compound." In principle, I think that's fair. When I buy stocks, I try and ask myself "is this a stock I feel comfortable never selling?" But venture, as an industry, doesn't necessarily work that way.

By design, venture capital has a structured timeline. Funds have specific time frames, typically 10 years. The longer those funds take to return capital, the more their IRR is punished, and the more difficult it is to raise their next fund. And that isn't just venture funds. Most investors have some kind of time-constrained liquidity requirements that define their hold periods.

I think of it as a big game of hot potato. Founders have equity that they pass to seed investors who pass it to later stage investors who pass it to crossover investors that pass it to large hedge funds that pass it to retail investors.

Sometimes that's fine. You get paid for passing the potato because its a little cooler. One party took on risk when the potato was piping hot right out of the oven. The time that first party took holding the risk, they get rewarded for when the next person catches the potato. And with good companies, that's fine. People can keep making money on down the line (albeit less upside, but for less risk).

But every once in a while, you end up with less a nice game of hot potato, paying up for risk reduction, and instead end up with a good old fashioned bag holder.

That's one reason why most VCs can afford to not particularly care about the long-term economic engine of a company (or at least, they could for the last decade). It doesn't matter if you're pouring billions into a money inferno that is selling $2 for $1 because the company doesn't have to make money, you just have to find someone willing to believe the company will eventually make money (i.e. someone willing to hold the bag.)

Finding Your North Star

Going back to the Twitter conversation screenshot above; Ho Nam makes this phenomenal point about the very best companies:

"Here is the paradox. A company built for all stakeholders (not just VCs and not even for shareholders) have a better chance of being great. If you truly have a great one, getting liquidity is easy. Many ways to do it and time will be on your side. A great company can provide liquidity through dividends, shareholder buybacks/tender offers, secondary transactions, IPO and M&A. There will always be interested buyers of rare, great assets. Hard to get liquidity in bad ones, unless there is some fraud. Lipstick on pigs."

The key implication I come away from this thought process with is that VCs are too often focused on funding companies that represent "passable bags" rather than long-term exceptional companies. Being able to say, "this is a company whose stock I never want to sell," is a more likely way to see exceptional companies, as opposed to piggybacking on passable bags.

It was really cool to see Deep Nishar speak at a recent conference where, after being at Google from 2003 to 2009, he's been an executive at Linkedin, and an investor first at SoftBank and now at General Catalyst. And when talking about Google, he said "I still hold the stock I got in 2003."

So on one end of the spectrum you have the view that the company building ecosystem has largely been driven by a misaligned group of incentives. You have a generation of VCs that have largely been investing in passable bags, and a generation of companies that have been building economic engines that are only good at one thing: lighting money on fire to "say the bigger number."

An Existential Turn

But let's look at the other end of the spectrum. A much more existential view. A few years ago, Ben Thompson wrote a piece called the The End of The Beginning. In it, he compares the evolution of the auto industry to tech.

"By 1920, automobile manufacturing was already dominated by GM, Ford, and Chrysler. Cars were the foundation of society’s transformation, but not necessarily car companies. There is an implication in the “generational change is inevitable” argument that paradigm shifts are sui generis. The personal computer was a discrete event, the Internet another, and mobile a third. Now we are simply waiting to see what is next.

[But] there may not be a significant paradigm shift on the horizon, nor the associated generational change that goes with it. And, to the extent there are evolutions, it really does seem like the incumbents have insurmountable advantages: the hyperscalers in the cloud are best placed to handle the torrent of data. In other words, today’s cloud and mobile companies — Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, and Google — may very well be the GM, Ford, and Chrysler of the 21st century.

Thompson wrote that post in January 2020, before COVID, the tech pull-forward, macro correction of 2022, or AI revolution that we've seen in the last 6 months. He wrote a follow up the next day where he laid out why his case wasn't just one of default pessimism. I'd be curious to see his take now as AI is advancing.

But I think his take would remain relatively the same. Already, we're seeing the hot takes of skepticism roll in on AI. Again, and again people have articulated why, unlike SaaS, cloud, or mobile, there is an inherent advantage for incumbents when it comes to AI. The need for (1) massive volumes of data, and (2) massive amounts of compute mean that it's a much more difficult landscape for startups to play in. That's why OpenAI, as impressive as it is, shouldn't be thought of as just another great startup story. But it's mostly a very exciting side-bet for Microsoft. That's why they've put in $10B+.

So Where Does That Leave Us?

Companies are a reflection of the time they're built in. The industrial revolution anointed the most wealth to oil barons, railroad tycoons, and steel magnates. The digital revolution did the same for ad pushers, same-day shippers, and search aficionados.

Investors are allocators of capital, but capital has always been a function of attention. "What gets measured gets managed." Where you look is where you'll throw. In a zero interest rate world, there's always more cash to burn. But are you burning it in favor of the biggest number?

It's no surprise that in an ecosystem built around extraordinary growth the incentives get aligned to drive a specific number; a specific type of company.

"Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome." (Charlie Munger)

What has been the most significant cause of existential reflection for me has been how difficult to believe the present will be similar to the past, despite having thousands of years of "the past," and only a few months of "now." Everyone has to define for themselves what game they want to play. Do you want to build generational long-term value in everything you do? Or do you want to build passable bags?

To each their own. But the data laid out here should indicate that the paradigm of the last decade probably wasn't the best model for capital allocation. And we could all be more thoughtful about the longer-term implications of how and what we're building.

Thanks to Jared Sleeper and Sebastian Duesterhoeft for jamming with me on this topic.

What I’m Reading

Elon Musk isn't even an interesting Republican by Alex Wilhelm

Parker Conrad Takes the Pain by Abram Brown

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week: