This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

A few weeks ago I wrote about The Siren Song of Raising a Venture Fund. In it, I talked about how I'm seeing more and more new venture firms pop up. This was something that, candidly, as the market hardened around everything except AI, I didn't expect to see.

In that piece I quoted Fred Wilson as saying, "We don't need a few firms managing billions of dollars. We need lots of firms managing a few hundred million dollars." When I wrote it, I couldn't remember where I'd heard it from or written about it.

(Big thanks to Chris Harvey for trying to help me find the quote, and to Abhishek Singh who eventually helped me remember I wrote about it in The Blackstone of Innovation.)

After writing about it, the quote had stayed on my mind so I tweeted it out this past week.

The responses to the tweet were super interesting and got me thinking about a topic I've written about a lot, most notably in The Puritans of Venture Capital:

Venture fund size.

Both in the responses to my tweet, and in general, this can be a pretty polarizing topic. As I reflected on people's responses for or against this sentiment, I was reminded of the Upton Sinclair quote:

“It is difficult to get a [person] to understand something, when [their] salary depends on [their] not understanding it.”

For example, one of the most aggressive responses against this sentiment came from Brett Adcock, the CEO of Figure, an AI robotics company building humanoid robots.

No disrespect to Brett, he seems like a cool guy, and Figure seems awesome. But, in terms of where his incentives lies, he talks about how much Figure has raised right in his Twitter bio.

The biggest contender for the pro argument came in the comments of Brett's post from Sarah Guo, the founder and GP of Conviction, a $101M seed fund. Sarah made the argument that SpaceX, arguably the most important "big swings" of building an “exciting future,” was first supported by Founders Fund out of a $202M fund.

Brett shot back that, today, the assets under management (AUM), or the sum of all the funds that Founders Fund has ever raised since being founded in 2005, is $11 billion.

The back and forth awoke in me the need to unpack a nuanced argument. Because, as is often the case with the arguments I find myself most attracted to, there is a lot of nuance. And it’s hard to say any one perspective is right or wrong. Instead, I'm more focused on making sure people understand the implications of one or the other. So let's do that.

The Business of Venture Capital

I feel like I've written about this over and over again that I don't even wanna go back and find every time I've done it. I'll just quickly recap.

The important thing that most people don't appreciate about the "business" of venture capital is that its very different than the "marketing" of venture capital.

The marketing of venture capital is important. Being founder friendly, etc. — all of that is how VC firms talk about themselves to make sure founders know that they're the main character.

But the business of venture capital is an asset management business. Maybe in the wild west days of Arthur Rock and Don Valentine, VCs were rolling up their sleeves and getting in the trenches with founders neck and neck, risk for risk. As venture has become both more professionalized and more on the radar of large asset managers, it has become more and more an asset management business. Even for the VCs that say this isn’t true, and they’re in the trenches, ask them, “If my company fails, will you shut down your venture firm?” And if the answer is no, then you know that VCs and founders are NOT the same.

Venture investors are general partners in a partnership with limited partners. Limited partners (LPs) have capital, be it family offices, sovereign wealth funds, pensions, etc. These LPs are people whose jobs are defined by the fact that somebody, somewhere has money lying around. And the gospel of compound interest has only one cardinal sin: don't let money just lie around.

So these LPs deploy capital into funds in agreement with general partners (GPs) who actively dictate how that capital is deployed.

As any good red-blooded capitalist does, GPs have a profit motive. How do they make money? Two ways: fees and carry.

A typical fund has a 2 and 20 model. If you raise $100M or $10B, you will typically get somewhere around 2% of that total each year to pay salaries, expenses, etc. Then, you have an agreement with LPs that, once your return the original money they invested, you'll get to keep 20% of any upside.

Again, as the true-blue American capitalist that they are, VCs will typically work to optimize those two profit drivers.

The important thing to note here is that these two profit drivers are driven off of two fundamentally different things. Fees are driven off AUM. The bigger the AUM? The bigger the fees. Carry is driven off returns. The better your returns? The bigger your carry.

And maximizing fees vs. maximizing returns are not only fundamentally different games, but are in many ways diametrically opposed. The bigger your AUM, the worse your returns. Understanding that dichotomy is fundamental in understanding the strategy of many (though not all) venture firms.

The Size of My... AUM

Going back to Brett's argument about AUM, "big multi-billion dollar firms funded SpaceX, therefore the primary virtue is in that firm having a big AUM." Sarah's point is very correct. SpaceX DID get started with support from a relatively small fund. AUM is a nuanced number that most people don't understand very well.

AUM isn’t even really a scorecard exactly; it’s more like office square footage. True, it does demonstrate the size of your footprint, but it doesn’t necessarily indicate your strategy or success. If you have a big office square footage footprint, it’s even fair to say you’ve been successful, at least by some metric or measure of time.

But you know who has had big offices? Theranos, WeWork, Quibi, and Hopin.

You know who had a lot of cash? Theranos, WeWork, Quibi, and Hopin.

Firms like Tiger Global and SoftBank have touted ungodly amounts of capital as a demonstration of their capability. Tiger Global deployed $19 BILLION over the course of 2020 and 2021! SoftBank's Vision Funds have aggregated $156 billion over two funds. That's almost 2x the AUM of Sequoia. If AUM is the game, those are solidly in a leading bucket.

But AUM alone doesn't lead to successful outcomes. What it can lead to, however, are some pretty rich fees. Going back to the business of venture capital, you can get a lot of enrichment out of maximizing AUM. The larger the fund, the bigger the fees. You raise a $5B fund? You have $100M coming in each year.

Though it’s a fair point to make, you typically don't get to raise billion dollar funds without having previously been successful. SoftBank had Yahoo and Uber, Tiger Global had built a massively successful public investing book. But, as any good compliance officer will tell you, past performance is not indicative of future performance. It is also true that there is some awesome research supporting the idea that the best venture funds persist in returns. Other people have called this the halo effect. But ongoing success isn't a bygone conclusion.

Success is a matter of on-going strategy and capability. I've written before about the Red Queen Hypothesis vs. the Lindy Effect. On the one hand, the Red Queen Hypothesis is, effectively, "no species has more right to survive just because they've been around for a long time." On the other hand, the Lindy Effect, states that "the future life expectancy of some non-perishable things, like a technology or an idea, is proportional to their current age.

So are venture funds biological organisms that are subject to the laws of survive, thrive, and extinction? Or are they conceptual entities whose potential for longevity increases as their duration of existence persists?

Who knows. But I'm of the opinion that venture funds are biological organisms. Companies, funds, any organization — they're all a function of the people inside. And the better or worse the people inside are, the more likely that organizational organism is to live or die.

A Non-Binary Matter of Degrees

Now, I can't emphasize this enough. Big funds are not inherently bad or evil, any more than big companies or big countries or big dogs are inherently bad or evil. I’m not morally opposed to large funds any more than I’m morally opposed to large companies.

If we go all the way back to the logic behind Fred Wilson's comment, that we should have lots of venture funds managing $100M vs. a few of them managing $10B, the logic is a function of compounding. It is easier to generate bigger returns on smaller pools of capital.

I went into this nuance in excruciating detail in The Puritans of Venture Capital. As more and more firms have grown in size, and become “Capital Agglomerators”, their returns expectations have gone down. Big, multi-billion dollar firms aren't expecting 5-10x returns. They're expecting 1.5-2x returns. In my Puritans piece, I explained it this way:

"If Capital Agglomerators are targeting 2x funds, and Cottage Keepers have higher expectations for their small funds, at 5-10x returns, then we have a problem. If both are competing for a different outcome, then one is willing to pay a higher price than the other. Here's the scenario: one Cottage Keeper and one Capital Agglomerator are competing to invest in a company with $5M ARR. Cottage Keeper: Bids $250M; believes the company can grow into a $2.5B outcome, and that could generate their 10x return. Capital Agglomerator: Bids $1B; believes the company can grow into a $2.5B outcome, and that could more than generate their 2x return. Even if these two firms have the same fundamental belief in the company's outcome, their return threshold enables them to play different games.

You might come to the conclusion that bigger just means better. The bigger you get, the more swings you can take, you can take bigger losses, and have lower expectations.

But there is a fundamental bottleneck. Not every company can be a really big success. And building a model around massive pools of capital that require massive outcomes to move the needle will increasingly give investors "nail goggles" and they'll take their hammers, and just start swinging. But in the process, they'll shatter a lot of good businesses trying to form them into $10B+ outcomes.

Where's The Bottleneck?

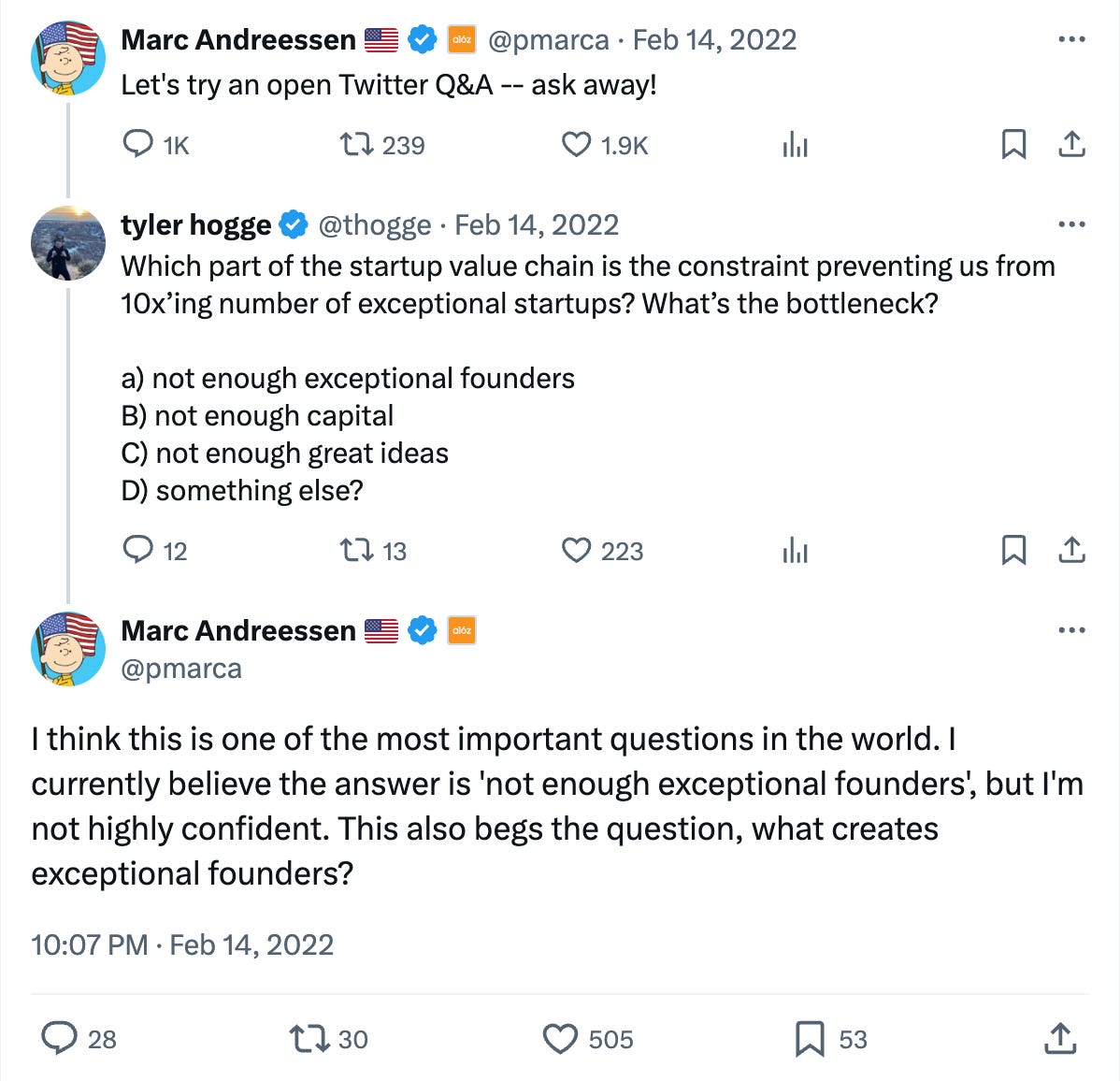

I think often of a Twitter AMA that Marc Andreessen did a couple years ago. One of the questions, in particular, that has always stuck with me, was this one about bottlenecks:

"One of the most important questions in the world." I couldn't agree more. But even before we can get to this incredibly important question, there is a necessary premise to accept; that there are bottlenecks to "10x'ing the number of exceptional startups!"

There is a premise behind Brett's admonition: "if you want great companies, you need more capital. If you want dinky productivity apps, then sure. Have less capital." His premise is, effectively, that he would answer Tyler's question by saying "not enough capital." But Marc and I both fundamentally disagree with that premise.

[INSERT GREAT FOUNDERS HERE]

Unfortunately, I am not going to author a reality-bending response here to Marc’s question, "what creates exceptional founders?" because I don't know the answer. But its important to not just leave this thought bubble hanging. This is an important question to answer.

But as it relates to the broader discussion of venture fund size, the merits of AUM, and what unlocks the "exciting future of robotics, electric aircraft, genetics, nuclear, space," its enough to clearly state that capital is NOT the primary constraint in world-bending innovation. From 2002 to 2024, SpaceX has raised ~$10B. From 2002 to 2024, the total budget of NASA was $435B. If capital was the only mighty unlock needed, NASA would own the moon and we’d be celebrating the opening of the first McDonalds on Mars by now.

And, in fact, dumping more capital into a supply constrained market can actually result in throwing the baby out with the bath water. Let me explain.

The Threat of Capital Destruction

Despite economic growth, endless money printing, and diamond hands HODL gospel, it is a reality that there is a finite amount of capital that can be deployed. Is it massive? Yes. Is it constantly fluctuating? For sure. Is it determinable? Kinda. But one thing is for sure; it is finite.

In a world of finite capital it means that ideas and investments have to be prioritized. What deserves to be invested in and what doesn't? And the world is replete with examples of unspeakably bad capital allocation. Dramatically terrible ideas that have amassed and destroyed billions of dollars. But, to some extent, this is the cost of doing business. You can't make an omelette without breaking a few eggs.

I've written several times about a since-deleted Harry Stebbings tweet (that I'll never let him forget) that I've always thought was accurate, and have generalized for this conversation:

"Effectively his point was that there is a natural selection among startups. Not every company will survive and it can be a healthy recycling of [resources] back into other companies. In a world of abundant capital fewer companies are dying, which means [resources don’t] recycle as often."

So the more companies die, the more opportunity there is for some of those companies’ resources to recycle back into the ecosystem and get reallocated (hopefully more effectively this time). And that reality, while sad in the moment, is good for the overall ecosystem.

But when we start thinking like Brett, believing that just dumping more capital into the system will create more successful outcomes, we fail to recognize the premise of the bottlenecks tweet; that bottlenecks exist.

If you dramatically increase the volume of capital without unlocking the volume of good companies to invest in, you ensure a higher volume of capital destruction. And you might think, "well, Kyle. More broken eggs, more omelette's, right?" Wrong. Eventually the pan overflows. Then you're just left with an ungodly amount of smashed eggs on the ground. And maybe the person who was giving you eggs to make the omelette will be much more hesitant to give you more eggs in the future.

Recently, Katie Roof wrote a piece titled In Venture Capital, the Rich Get Richer. In it, she described the conservative concentration LPs are engaging in:

"Investors in VC funds, or limited partners, “have become more selective and cautious,” research firm PitchBook said in a recent report. At the same time, average funding has fallen. One reason for the pullback is that startup valuations are languishing in most sectors outside of artificial intelligence, and returns have stalled."

Michael Eisenberg was quick to point out the same thing I mentioned before; the awesome research supporting the idea that the best venture funds persist in returns. He also made a similar point as Harry Stebbings about recycling:

"Contraction in VC market is a feature and not a bug because it enables great entrepreneurs to raise money and mediocre ones to fail. That means cost to build company goes down due to less competition for resources."

All of these points about capital, resources, etc. recycling are signs of a healthy ecosystem that are rebalancing to seek healthier capital allocation. But what happens when you push the capital destruction too far?

Right now, we're at a place of reticent "flight to safety." LPs have gotten nervous about the exorbitant excesses of 2021, the dramatically irresponsible valuations, the minting of literally TWO UNICORNS PER DAY on average. They didn't care for that. They didn't care for the massive IPO wipeouts of companies like UIPath going from $35 billion to $7 billion or Instacart from $39 billion to $9.3 billion.

So, in response, they've started to concentrate. a16z, Thrive, Kleiner, ICONIQ. While smaller or newer funds have scrimped and saved to raise a few hundred million, the Capital Agglomerators have racked up billions in new funds. Again, that's not necessarily bad.

But I can't tell you the number of times I've had conversations with LPs who are desperately anxious.

They see these big, established, successful firms hawking into companies with no revenue at multi-billion dollar valuations because they whispered the majestic letters; "A and I."

Companies that, after raising at a multi-billion valuation, are framed as being "in anticipation of its platform getting traction and working as envisioned." That's a pre-seed memo, not a press release for a multi-billion dollar valuation in a funding round.

Some firms, while being large, have still made attempts at being responsible stewards of capital, like in early 2023 when Founders Fund chose to reduce its eighth venture fund from $1.8B to $900M. It wasn't that they couldn't raise the size of fund they wanted; they told LPs they wanted the fund to be smaller, and pushed capital out of that fund.

And don't get me wrong, I'm hopeful that more and more of these massive firms can be responsible stewards of capital. I want there to continue to be great successes and outcomes that will continue to alleviate LP's concerns and continue to build the pool of capital going towards big, ambitious ideas.

But I've worked with a lot of these firms and I gotta say, I'm not super optimistic. And the existential danger to all of us, from the funds that want to be big or small, to the founders that want to build productivity tools or humanoid robots, is that the more irresponsible the biggest firms continue to be, the more capital gets destroyed, the more we run the risk of chasing a large volume of capital out of the asset class.

Fewer LPs investing in the asset class is a much surer way to make it harder to have enough capital to take big swings at ambitious projects, like humanoid robots. So no, dumping more capital into the ecosystem is not the solution. Big funds can still exist, and do awesome work. I don't hate them. But bad strategy will continue to push us towards the Hits Business I've written about before, which could lead to a lot of high profile pains that spoil the ecosystem in much worse ways.

Slow & Steady Wins The Race

Do I want more innovation? Absolutely! Do I want bigger and bolder ambition, chasing everything from preventing aging to colonizing the stars to giving everyone all the food, shelter, and happiness they can stand? Undeniably.

But doing too much of anything in pursuit of something good will often lead to the exact opposite of the result you were hoping for.

If you want to build huge muscles, you can't work out 24/7. You'll tear your muscles, never recover, and probably die.

If you want a baby, you can't just have sex 24/7. You'll get dehydrated, hurt something, and probably die.

Moderation in all things.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Good article. I did think you brought in too many other peoples voices on the second half so it became a list rather than a synthesis.

PS: FYI I think Hopin was remote only / but your general point stands bigger isn't better

I agree on the main points here, loved reading it and will check out the previous ones. Plenty of insights and some nice "business trivia". Not sure if it needed this amount of words to claim the arguments, though.