The Siren Song of Raising a Venture Fund

"Half the budget is a waste; we just don't know which half."

This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

The Death of Venture?

Reminiscent of a Mark Twain quote I've written about before, "the reports of the death of venture capital have been greatly exaggerated." Since 2021 collapsed into a frenzy of fear-filled malaise, people have been wondering about the future viability of venture. Some people see AI as a dead cat bounce; yet another hype cycle to convince people that venture still makes sense.

I, myself, have touched on aspects of "death" in venture over and over and over again. I touched on it this way:

"Venture capital is an existentially flawed, yet powerful, economic system that could kill the thing most VCs purport to love: startups. The dissolution or rapid revolution of the venture capital industry threatens to kill a generation of tried-and-true VCs."

In two pieces I wrote about broader company consolidation at the beginning and end of 2023, I also touched on the possibility that venture funds could get acquired as one path forward while things change.

Across all of those pieces I touched on different predictions, like Josh Wolfe saying "between 50% and 75% of the active investors in private markets today will disappear in the next few years." Or Alexander Niehenke saying "25% of partners at VC funds will exit the business in the next few years."

In 2022 when things were hitting the fan I really thought the mantra in venture going forward would be "consolidate or die." And to be sure, you've seen a few firms shut down, like OpenView or Foundry Group, but those had more to do with succession vs. market conditions.

Capital Agglomerators

Instead, the more dominant force I've seen in venture over the last few years is the continued bifurcation of capital into its own power law. I've written about this dynamic before in The Blackstone of Innovation and The Puritans of Venture Capital. Capital agglomerators that start to suck up the vast majority of capital. A16z raising $7.2B. ICONIQ raising $5.75B. Index raising $2.3B. On and on.

As the fundraising environment has been less approachable the ability to raise capital for venture funds has certainly been more difficult. I've described it before as an "income inequality effect" in both venture and startups. The companies and funds raising the most capital continue to suck up a huge chunk of the attention, while the rest get less and less.

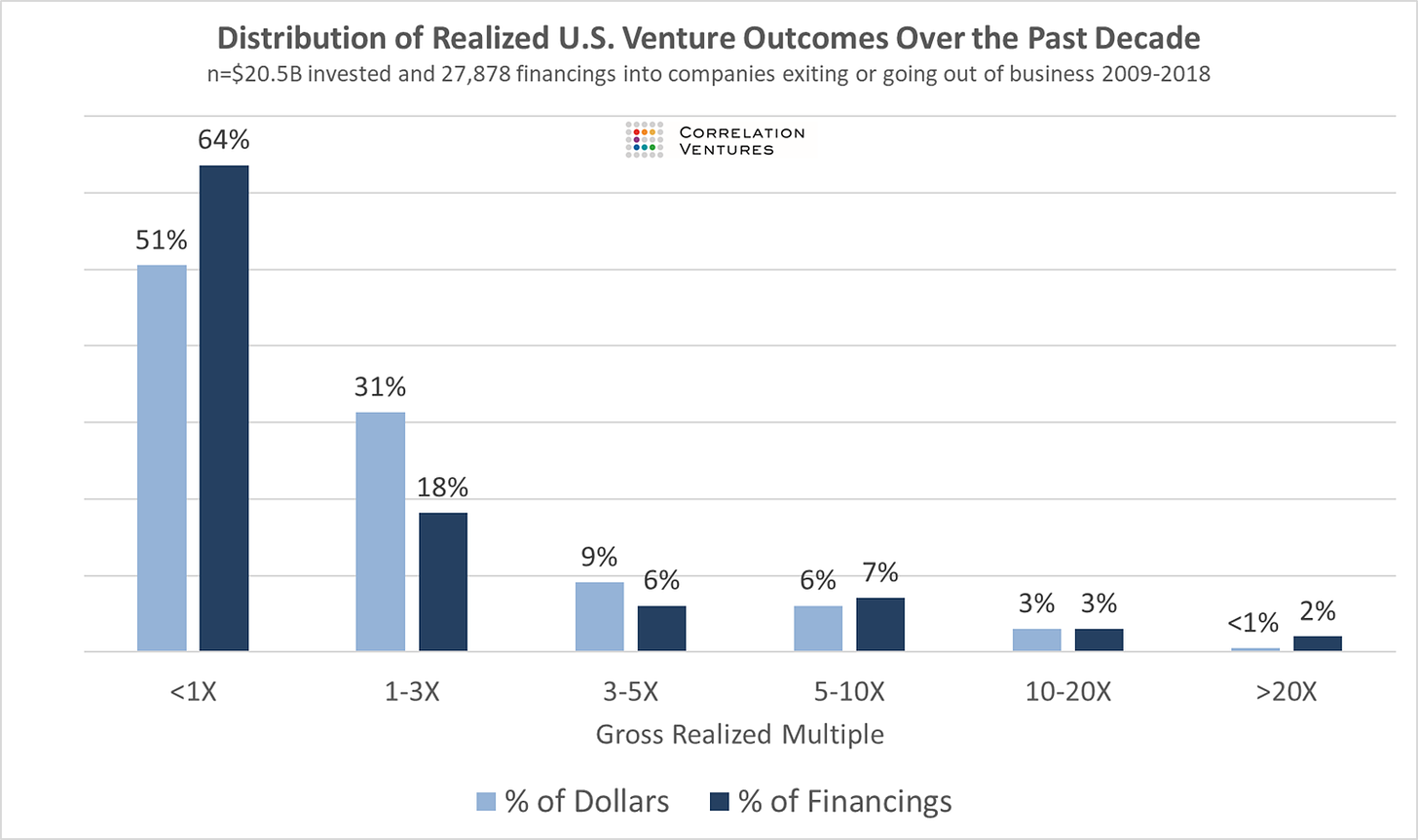

Despite the dominance of these mega fund capital agglomerators there was still the painful reality staring everyone in the face: the ability to compound capital diminishes as the size of the capital pool gets larger. It's statistically much harder to generate venture-like returns on $1B of capital.

The thing I've pointed out about capital agglomerators is that they don't necessarily need "venture-like returns." Firms like a16z and ICONIQ play a different role. They allow massive financial institutions to deploy $200M+ at a time. And no one is expecting to 10x a $200M investment. They're satisfied with a 2x here and there.

The Cottage Keepers

Venture-like returns are, instead, built by organizations that maintain a smaller, constrained capital base. Firms like USV who, despite being asked by LPs to raise $1B+ funds, have maintained $250M fund sizes.

I'm so frustrated that I can't find the quote because I'm 100% positive I've written about it somewhere in my blog, but I remember a couple months ago, Fred Wilson (I think) spoke in New York (I think) and said, in effect:

"We don't need a few firms managing billions of dollars. We need lots of firms managing a few hundred million dollars."

If you can find the quote, please send it to me (it might even be that you can find it in my own writing). I'd love to update it.

But that concept of maintaining a higher number of funds managing smaller fund sizes certainly makes sense to me. Speaking of Fred Wilson, he's also laid out the math on what it takes in terms of proceeds required to generate the necessary returns on the amounts of capital being managed. TLDR: It's a LOT.

But despite the logic in smaller funds being more capable of compounding capital, you can just feel the pull towards larger and larger funds. People can make more money off of fees, build larger organizations, more definitive brands, and compete for the best deals.

The Smoking Gun in Venture

In particular, one of the things I've pointed out before is how different firms of different sizes are playing different games, despite competing with each other:

"People will ask, "how, in 2023, can you do an investment with a few million of ARR for a $1B valuation?" Because capital agglomerators, by attracting massive LPs who are giving them $250M a pop, are playing a dramatically different game. No LP expects 10x returns on $250M of capital. They're more than happy with 2-3x returns. So those firms are underwriting very different outcomes. They just need those $1B entry prices to become $2-3B companies. Is this the stupider game? Not necessarily! It's just a different game. So what's the stupider game? For other VCs, its not realizing that you're competing with someone who is playing a very different game."

If you think you're playing soccer and your opponent thinks you're playing football (the American kind) then you better believe you're about to lose. Because they're going to smash into you with reckless abandon.

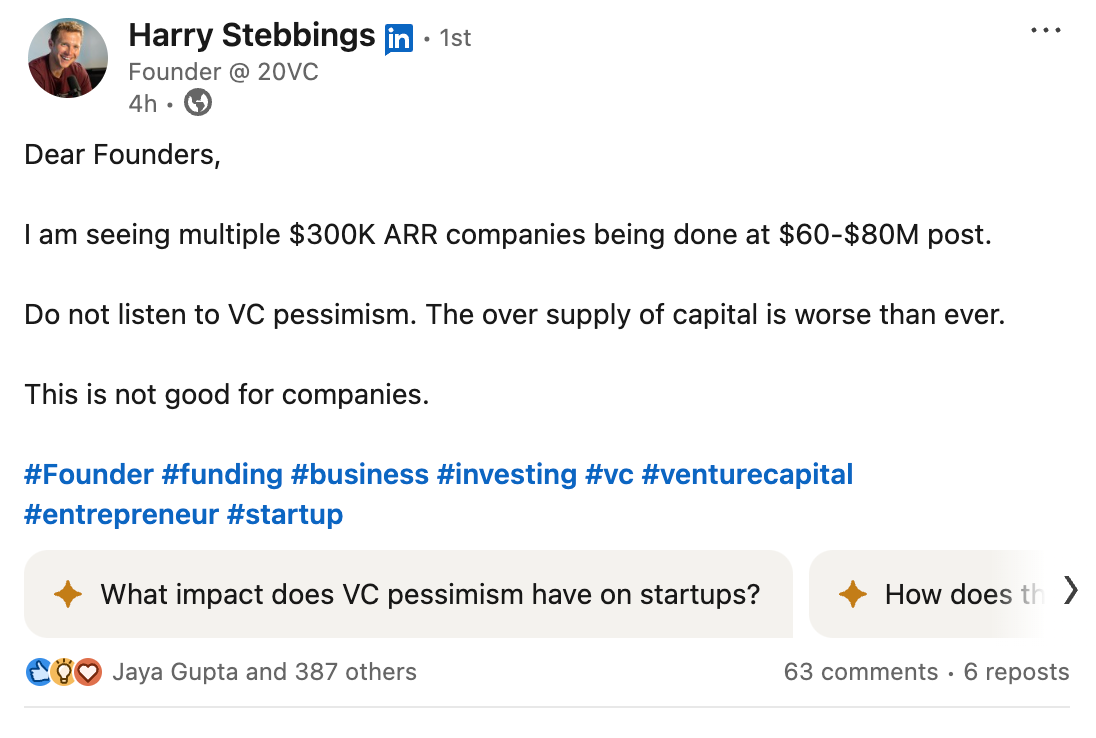

You see this dynamic at play in posts like this where people are freaking out about huge valuations for very little traction.

So often, people chalk it up to an "over supply of capital." I think that's only part of the picture. The massive increase in supply of capital has come because capital agglomerators, like a16z and ICONIQ, have created a product that allows LPs to get into the game who otherwise wouldn't have. Organizations that are managing $20B+ can't afford to go put $5-10M checks into dozens of small funds. But with capital agglomerators, they can deploy $200M+ at a time.

I had a similar conversation with some friends when we were talking about ICONIQ's recent investment in Coast, an expense management platform that compares itself to Ramp or Brex, but for fleet operators.

A friend asked "how is it possible that all these expense management companies raise money?"

Understanding the approach of these capital agglomerators makes it make a lot more sense. Expense management is a TRILLION dollar market. If there’s even a slight chance it becomes a breakout, that’s worth risking $40M.

Even if ICONIQ invested $100M in a Series B company, the risk on that investment is very different than a typical fund. ICONIQ is managing a $5.75B fund (not $5.75B AUM; that's just one fund amidst $80B of AUM). So if that $100M goes to zero, that's just 1.7% of the fund. Well within the loss ratios of a typical seed fund. So, again, these firms are just playing different games.

So a combination of the formidable force of capital agglomerators, the denominator problem with LPs who suddenly have over-exposed themselves to illiquid private markets without the liquidity to justify it, and the general fear people have of the broader macro climate — all of this led me to believe that few, if any, investors would start a brand new venture fund right now.

But I was wrong.

The Surprising Upstarts

People continue to raise venture funds. Brand new funds with new strategies, new brands, and new focus areas. From my old pal, Rex Woodbury, raising Daybreak, to my other Index buddy, Mark Goldberg, raising a fund with Kristina Shen and Ethan Kurzweil. Another one of my former colleagues, Maya Noeth, announced she's leaving Accel to start a new fund. Most recently, Blake Robbins left Benchmark to raise a $60M fund and Gaurav Ahuja left Thrive to raise a $30M fund.

There are dozens more. And these are solid investors coming from name-brand funds all raising funds. Some people can balk at this, especially those familiar with the fundraising environment right now. "How could anyone raise a new fund right now?" But already I've seen new funds successfully raise their target amounts, win investments, and start to build their reputations.

My takeaway is that as venture capital continues to be unbundled there is an increased opportunity for better productized venture firms.

I come back to the idea in marketing that "half of our marketing budget is wasted; we just don't know which half." The same is true in venture. Probably 90% of venture funds shouldn't exist. But we don't know which will be the 10%. And the ones that were the 10% five years ago won't necessarily be the 10% today. So we're all in competition to be in that top that deserves to live.

Maybe the picture is rosier. According to Fred Wilson, 50% of venture funds beat the S&P 500. So maybe its more in-line with the marketing quote after all.

So, optimistically, venture funds should continue to exist. And I, for one, am excited to see a deeper productization of venture offerings. How can we, as an industry, work to create better products for the founders we serve? And how can we compete with capital agglomerators that are playing fundamentally different games? To end with another Fred Wilson quote (at least this one I can find):

"Big firms with $5 billion are not your friends. We're your friends. We hold companies for 20 years because we allow companies to stay private for a long time."

Obviously everyone is going to present their own case as ideal. But the reality is that in the same way ICONIQ can lose $100M because its 1% of their fund, they can also choose not to care about you as much even if things are just going fine, but not gangbusters, because you're 1% of their fund.

So from my perspective there is still plenty of value to create as a venture fund. And there are still plenty of vectors on which to compete in venture. Firms like Sequoia and Accel had been around for 40+ years when a16z came along in 2009, but they still made the incumbents dance. And I'm sure there are firms that are just getting going today that are going to do the same.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

our industry had changed/is changing

Great post. We wrote a piece on a similar theme on how the indexing of VC is gathering pace.

The private markets are becoming more like the public markets.

https://signalrankupdate.substack.com/p/indexing-vc-gathers-pace