This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I've said it before, and I'll say it again. In 2008 one of the most important experiences in my life was making sure I argued with all of my friends about which movie was better; The Dark Knight? Or Iron Man? Meanwhile the world was experiencing one of the five worst financial crises in history that led to a $2 trillion loss globally.

But when I think back, I still think The Dark Knight was a better movie. One scene in particular I was thinking about recently. There are two boats. One is filled with convicts, one is filled with regular people. The boats are stopped, and each are told they have a detonator to a bomb strapped to the other boat.

The perpetrator of the bomb switcharoo? The Joker. He tells each boat that if they blow up the other boat, then they'll live. If neither pulls the trigger? He'll blow both of them up. Pretty fascinating experiment in human nature. But the MVP of the experiment? This guy.

The guards on the prisoner boat don't want to pull the trigger, but they don't know what to do. The prisoners are starting to get ansy. Walking up to the guard holding the detonator, this guy offers a solution:

"You don't wanna die. But you don't know how to take a life. Give it to me. Or they'll kill you, and take it anyway. Give it to me. You can tell them I took it by force. Give it to me, and I'll do what you should'a did 10 minutes ago."

The guard hands it to him. And then this guy promptly throws the detonator out the window. So good.

You've got something that could kill a lot of people. Killing all those people would be awful. But if you don't kill them, you're going to die. You don't want to die. This guys response is ultimate. Remove the option. “I'm willing to die, if it means not letting something awful happen.”

Now, spoiler alert, thanks to Batman, nobody has to die. A boat full of people that "just showed you they're ready to believe in good." So how am I, yet again, going to turn an iconic moment of pop culture into a ramble about venture capital? Like this.

Venture capital is an existentially flawed, yet powerful, economic system that could kill the thing most VCs purport to love: startups. Just like the person who doesn't want to take a life on the boat — you're staring at a deadly thing. The deadly outcome isn't something you want. But the failure of that outcome threatens your own life. The dissolution or rapid revolution of the venture capital industry threatens to kill a generation of tried-and-true VCs. So what's to be done?

I'm staring down the barrel of cognitive dissonance where, on the one hand, I am a venture capitalist. And I want to keep doing what I'm doing. And I believe the model I'm leveraging can be valuable. On the other hand, I recognize the multitude of issues in the industry that create potentially more problems than they offer support.

First? We have to fight within the nuance. Just because something is broken, doesn't mean it needs to be taken back behind the barn and shot in the face. But once we defend our right to live? Then we have to come to terms with the need to change.

Don't Euthanize Me

"But Kyle, isn't all the murder and death talk pretty gloomy for a VC blog? Euthanasia is a bit much." The hyperbole is not mine to claim. That honor belongs to Edward Ongweso Jr. In March 2023, after the SVB blow up, he wrote a piece entitled "The Incredible Tantrum Venture Capitalists Threw Over Silicon Valley Bank." As part of that piece he took this pretty aggressive stance:

The increasing vitriol thrown at venture capitalists is as broad as it is creative: parasites, con artists, Venture Catastrophists, and (the most creative), ill-dressed rent-seeking oligarchic vampires.

So much of this specific drama was tied up in the back-and-forth frustration of what happened around SVB. I'm not gonna touch that too intimately. At the time, Mike Solana addressed this call for wiping out the "VC class" directly:

"Shortly after Ed achieved his goal of attracting attention from the people he dehumanized as “parasites” before suggesting they be euthanized, he clapped back, repeatedly and breathlessly, with a hopeless rolling of his eyes, and a kind of ‘do you see the idiocy I have to deal with.’ You’re all a bunch of poorly read losers, he argued. “Euthanized” is just a reference to famed economist Alfred Maynard Keynes! First and most obviously, there is a difference between “euthanasia” of a concept, and dehumanizing a group of human beings before suggesting they be euthanized."

In the same way that I'm not looking to unpack the SVB drama, I'm also not looking to unpack the complex web of politics driving someone like Edward Ongweso. The common thread from this aggressive stance towards VCs all the way to the actually important, and much more serious issues like the rise of anti-semitism globally, all runs through the idea of "identity value systems." I don't want to call it identity politics, because once you're calling for the death of a group of people you've stepped out of politics and started to demonstrate your value system (or lack thereof.)

People's overall frustration with venture capitalists as a group of people stems from a number of different big drivers. Here are just a few of them:

VCs are annoying: This is the easiest one and we can get it out of the way quick. True! Solana makes the same point in his response to the call for euthanasia; "for firms or venture capitalists with less of a track record, you’ve pretty much just got Twitter... This is a recipe for incredibly dramatic status games, all played loudly out online, which is just to say I get it. Venture capitalists really are, for the most part, incredibly annoying." There you have it. Moving on.

VCs have an undeserved celebrity in the startup community: Another easy one. True! People are often annoyed by how much attention VCs get. Also true. I've written before about how the ideal VC should be "the person that the person in the chair can count on." Too many VCs are intent, instead, on being the center of attention.

VCs don't do due diligence: People refer to VCs as "con artists," because they "no longer care if the companies they fund succeed. They have created a new math to declare themselves winners even when they are not." I've written before about the diligence deficit that exists in venture, and there's plenty of room for improvement.

VCs don't provide any real utility: Captain Euthanasia argues that one study pointed to limitations in VCs ability to actually fund things that provide utility: (1) VC and founder networks are very small and exclusive, (2) VCs exhibit herd mentality, and (3) the VC business model favors investments that "promise large returns in a medium time frame with minimal risk." I've written about most of these. "The Institutionalized Belief In The Greater Fool," and "The Blackstone of Innovation." The incentives of the venture business model do, in fact, reward structurally unsound thinking.

VCs are to blame for funding a myriad of detrimental innovations: Whether its defense, immigration, labor, transit, rental, or restaurant markets, people argue that startups have had more negative impacts than positive. I'll come back to that one.

VCs are obsessed with "new" over "good": Remember the sick "ill-dressed rent-seeking oligarchic vampires" burn? That comes from Nassim Taleb who accuses VCs of "injecting neomania," a "madness for perpetual novelty where ‘the new ’has become defined strictly as a ‘purchased value, ’something to buy.'” I'll come back to this one too.

Hating Players vs. Hating Games

The reality is, you can segment most of people's frustrations or (as homicide detectives call it) "motive," into three buckets: (1) personality, (2) process, and (3) outcomes. Number 1 is accurate; a lot of VCs are lame. Number 2 is the majority of what I write about; there is plenty of room for improvement. But saying someone's process could be better isn't a great reason to kill them. Finally, we're left with number 3: outcomes.

One of the strongest defenses for venture investing is the size of the outcomes. As much as VCs are annoying, and have a myriad of broken business behaviors, they have continued to put up numbers.

Amazon ships over 1.6 million packages per day. Over 2 BILLION people rely on WhatsApp each month to keep in touch with their families, run their businesses, and so much more. People ask Google 8.5 billion questions EVERY DAY. YouTube, iPhones, Stripe, Zoom, Fortnite, and dozens of others. Computers, microchips, vaccines, MRIs, and dozens of other things that the world runs on were in total or in part supported by venture funding.

Since the 1990s nearly $1 trillion of venture funding has been invested. A huge swath of that has gone to zero. But Apple, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook alone have a combined market cap of over $9 trillion, and generated $441 billion in operating cash flow in the last twelve months alone.

Now a lot of people can argue that a lot of technology has relied on government subsidies and support, inhumanely subsidized labor, monopoly price gouging, over-paid lobbyists, the selling of digital opioids, and radicalization of the misinformation campaign. And they’re not wrong! All fair points.

But it doesn't change the billions of people whose lives are better because of the technology that has been built. It doesn't negate the massive lifts to productivity and quality of life. The emotional relationships that are benefitted from increased social networking. The benefit my aging grandparents get from FaceTiming my children, or seeing their pictures on Facebook. Venture capital helped make aspects of life a little bit better. Whether you like it or not.

Yes... BUT

By now, a lot of VCs are nodding their heads. "Exactly! We're an important part of the ecosystem. Can't do without venture!" Not so fast.

Just because venture capital deserves to live doesn't mean it doesn't deserve to change. For an industry built around disruption and innovation, the venture industry sure is allergic to its own medicine.

The reality is private equity, as an industry, has attempted to hide behind an illiquidity premium, a long time horizon, and a lack of transparency. Just take this one footnote crime as an example:

On a chart meant to demonstrate the balance between returns and volatility, the footnote says "From 1Q86 to 4Q20 where data is available, deemphasizing 2008 and 2009 returns at one-third the weight due to the extreme volatility and wide range of performance, which skewed results."

The reality is every asset class is filled with storytelling and financial massaging. Every skeleton has closest, so lets talk about where those are buried for the venture world.

Saying The Quiet Part Out Loud

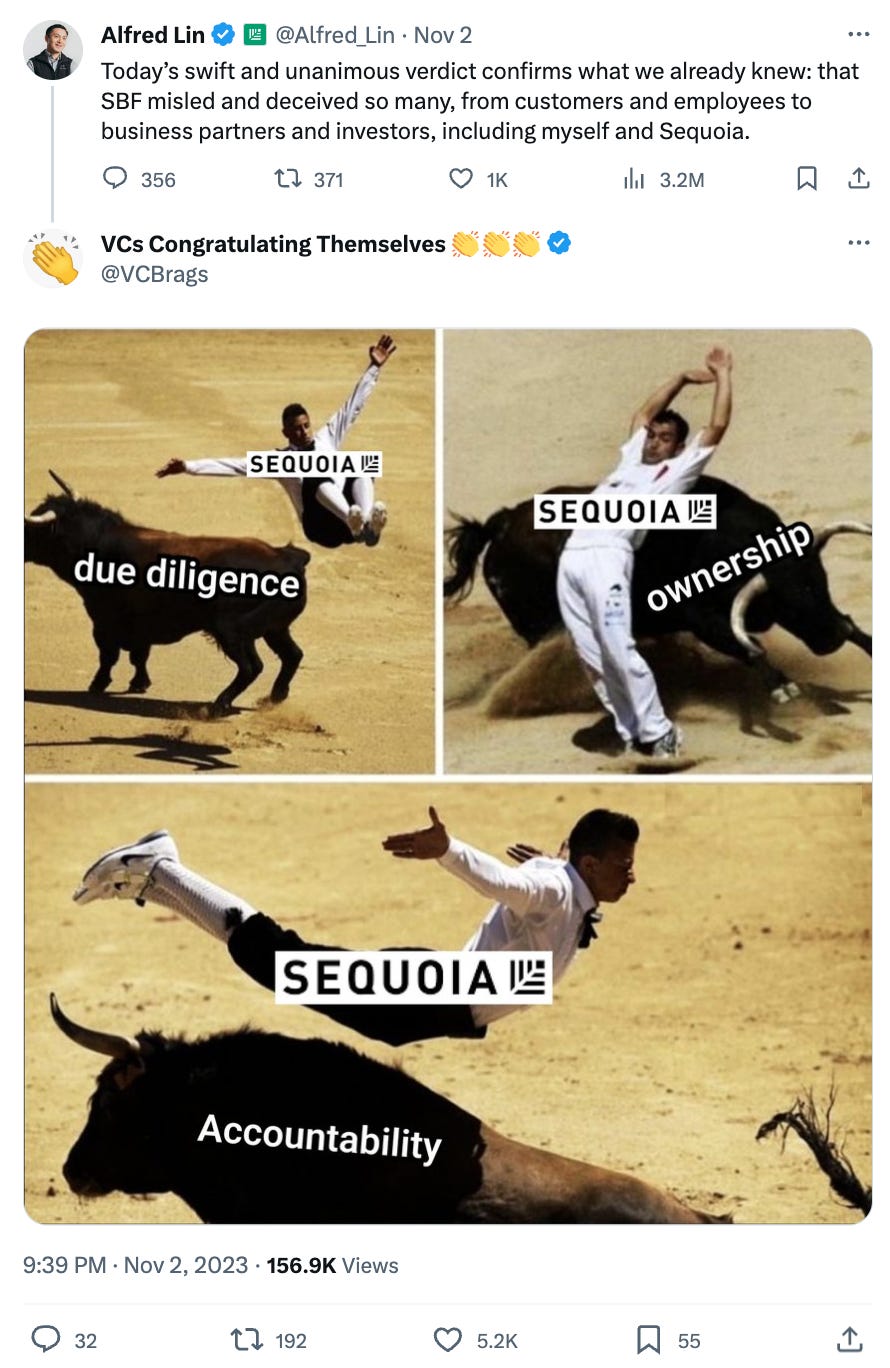

So much has been said about the weaknesses of the venture model. Venture firms have done dramatic damage to their brand value as a result of intense hype chasing and FOMO baiting. Even Sequoia, who is definitively one of the best multi-stage venture firms to ever exist, has gotten their fair share of black eyes, most recently (and notably) with FTX.

I've written before about a recent paper that came out called "Venture Predation." One overview of the paper described the conflict this way:

"Venture capitalists and the investors who put money into their funds aren't necessarily looking for a successful product (though they wouldn't turn one down). For VCs and their limited partners, the most profitable endgame is a quick exit — either selling off the company or taking it public in an IPO."

The paper goes on to make it more explicit with this gut-punch of a line:

"Critically, for VCs and founders, a predator does not need to recoup its losses for the strategy to succeed. The VCs and founders just need to create the impression that recoupment is possible, so they can sell their shares at an attractive price to later investors who anticipate years of monopoly pricing."

That quick exit, whether a through IPO or M&A is the mechanism through which you "create the impression" that the company has value to future investors (aka bag holders). In an episode of the All-In Podcast, Bill Gurley made the same point:

"I went and talked to some LPs who have been in the business for a very long period of time. And a vast majority of the reason venture outperforms other asset classes has to do with these tiny windows where you have a super frothy market... If you strip those years out of a 40 year assessment, it's actually not that interesting of an asset class. This highlights the need for venture funds to get liquidity at the peak. Right when we're at the peak is when people get the most brazen and confident and start talking about how we're going to hold forever. You had venture firms with the biggest positions they've ever had in their entire life go over the waterfall and evaporate what could have been returns."

This is the guy who invested $12 million in Uber, and got back $5.8 billion in returns. Meanwhile, after 10+ years, and billions of dollars, you still have Uber's CEO saying things like this:

“This next period will be different, and it will require a different approach… We have to make sure our unit economics work before we go big.”

I say again...

Venture Capital Deserves To Change

In the words of Upton Sinclair, "it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” People with a vested interest in something staying the way it is will always fight to convince everyone (including themselves) that it won't change. Nothing like a good macroeconomic correction and complete about-face of the public markets to force people to reflect on those arguments.

Things are changing. Venture is increasingly following a similar bifurcation to income inequality. On the one hand, you'll continue to have capital agglomerators. Their business model? Aggregate assets, deploy assets, collect fees, profit. On the other hand, you'll have the rise of product-led firms. They won't be defined by their AUM, but by the specificity of their product offering. This is a topic I haven't unpacked as much as I would like, but I will do it justice someday.

Scott Belsky made the point that venture funding, for both the investor and the funded company, has often been a function of ego. People start to see funding as the end point, the thing to be achieved:

"Financing is a tactic, not a goal. As I think about the implications of the new world of capital, I am most excited about the potential of very sober start-ups. We will see more startups bootstrap themselves longer, monetize sooner, and pressure test their business plan in ways that will prioritize product-led growth. Financing will become more tactical, and less of an ego-driven focal point."

As companies become more "sober," you'll see venture firms do the same. Patience, specificity, and the identification of inefficient markets represent the opportunity. Mike Maples had a great quote in a recent podcast episode called "Is The VC Model Broken?" He pointed to the potential that still exists for a venture investor:

"Patience is a form of arbitrage. The ability to play your game, to seek inefficient markets while everybody else is regressing the mean by chasing what's hot that is the arbitration. The arbitration is to be patient and to play that game when everybody else is playing the popular game."

So what game are you playing? As the venture capital model of the last few years starts to die, what rises from the ashes?

The Survival Guide

To respond to that idea, I can't help but think about Moneyball. There's a great line when the process is questioned for changing the game: "Adapt or die."

That's the key to survival. Adapt. Venture capital is dying because it has adapted to focus on returns. The model has crafted an engine that generates returns, not necessarily enduring, generational companies. The same is true of things like the oil industry. Eventually, companies will be forced to bear the brunt of their own externalities. Venture capital is no different.

Inhumanely subsidized labor, monopoly price gouging, over-paid lobbyists, the selling of digital opioids, and radicalization of the misinformation campaign. The pump-and-dump of radically blitzscaling an inefficient model to convince public markets that the upside is just getting started... it's not going to work anymore.

Companies like Udemy with $400M of revenue can see their stock price jump 38% in one day, just for crossing the threshold from unprofitable to profitable.

So if you want to survive in the ever-changing world of funding innovation, there are a lot of things you can do. But one thing is for sure: the only thing that is certain? Change. Get used to it.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

A world where a majority of startups focus on their unit economics / sustainable growth and building to enduring value (what timeframe does enduring even address) is certainly something I'd love to see come to pass.

It feels like there remain significant headwinds: from SOX pushing fraud to darker homes in private markets (Theranos, FTX on the extreme case to selective sharing in board meetings to remain in favor amongst the portfolio & in the bag passing game) to the temptation of personal rep boosts and partnership advancement in hitting big and fast from hollow/hyped wins to what might now be a generation of venture investors who haven't learned to ask these questions/push for this style of company building and maybe haven't even ever witnessed port co's who look like it...

Of course pre-pandemic investing had more scrutiny on fundamentals but there was still plenty of FOMO pre-empting and certain personalities more famous for that scrutiny than others. I'm curious your perspective on the likelihood to forget the fever dreams of responsible company building if the downturn recovers in some near/mid horizon and what that horizon length might be in your opinion?

Loved this 👏