This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I started writing consistently at the beginning of 2022 with only one goal: that I wouldn't miss a week. Since then, I've written 110+ pieces. In all of that time, I've written a lot of pieces that reflected important parts of my thinking. But they didn't always get the attention I thought they deserved, often because I wrote them early on before I had as many subscribers.

The Professionalization of Startups is one such piece. I wrote it in February 2022. But the core ideas are a big part of how I explain why many aspects of the venture and startup landscapes are playing out the way they are. So I thought it was worth revisiting.

Here, updated with some additional context I've gained over the last two years, is my revisited perspective on the professionalization of startups:

In Morgan Housel's book, "The Psychology of Money," he tells the story of Bill Gates' one-in-a-million life. And he wasn't talking about being a billionaire. Or starting a successful company. He was talking about having access to a computer in 1968.

Most university graduate programs didn't have a computer like the one Bill Gates had access to in eighth grade at Lakeside School in Washington.

In 1968 there were roughly 303 million high-school-age people in the world, according to the UN.

About 18 million of them lived in the United States.

About 270,000 of them lived in Washington state.

A little over 100,000 of them lived in the Seattle area.

And only about 300 of them attended Lakeside School.

Start with 303 million, end with 300.

One in a million high-school-age students attended the high school that had the combination of cash and foresight to buy a computer. Bill Gates happened to be one of them. Bill Gates has even said, “If there wasn’t a Lakeside there wouldn’t be a Microsoft.”

How crazy that we've gone from a one-in-a-million chance to even have access to a computer 50 years ago to now having 85% of adults in the US with a smart phone in their pockets one million times more powerful than anything baby Bill Gates ever had.

With the dramatic race forward in technology you’ve seen an explosion in the number of people who can build and scale technology companies. In just the last few decades we've gone from a small group of hobby hackers to a professional workforce of highly trained tech employees.

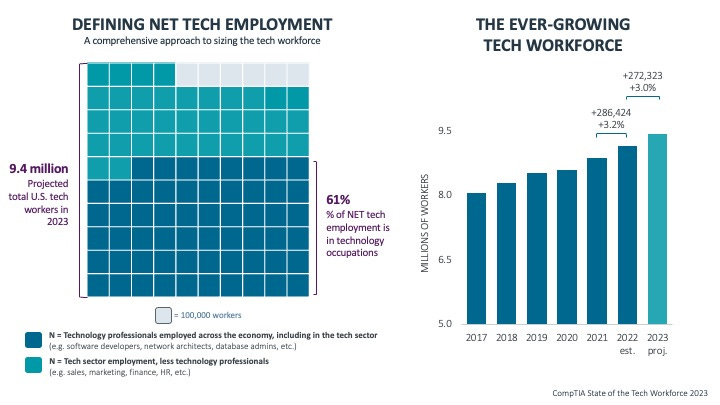

In 1970 you had a <1% chance of stumbling on someone working in tech. As the industry was just getting started in the mainstream during the 70s there was a total of 450K people working in the industry out of a population of 203M. Today? There are 9.4M, even despite 500K of layoffs since 2022. Nearly 2 million workers in tech are employed by Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Apple alone! (At least now you have a ~3% chance of running into someone working in tech.)

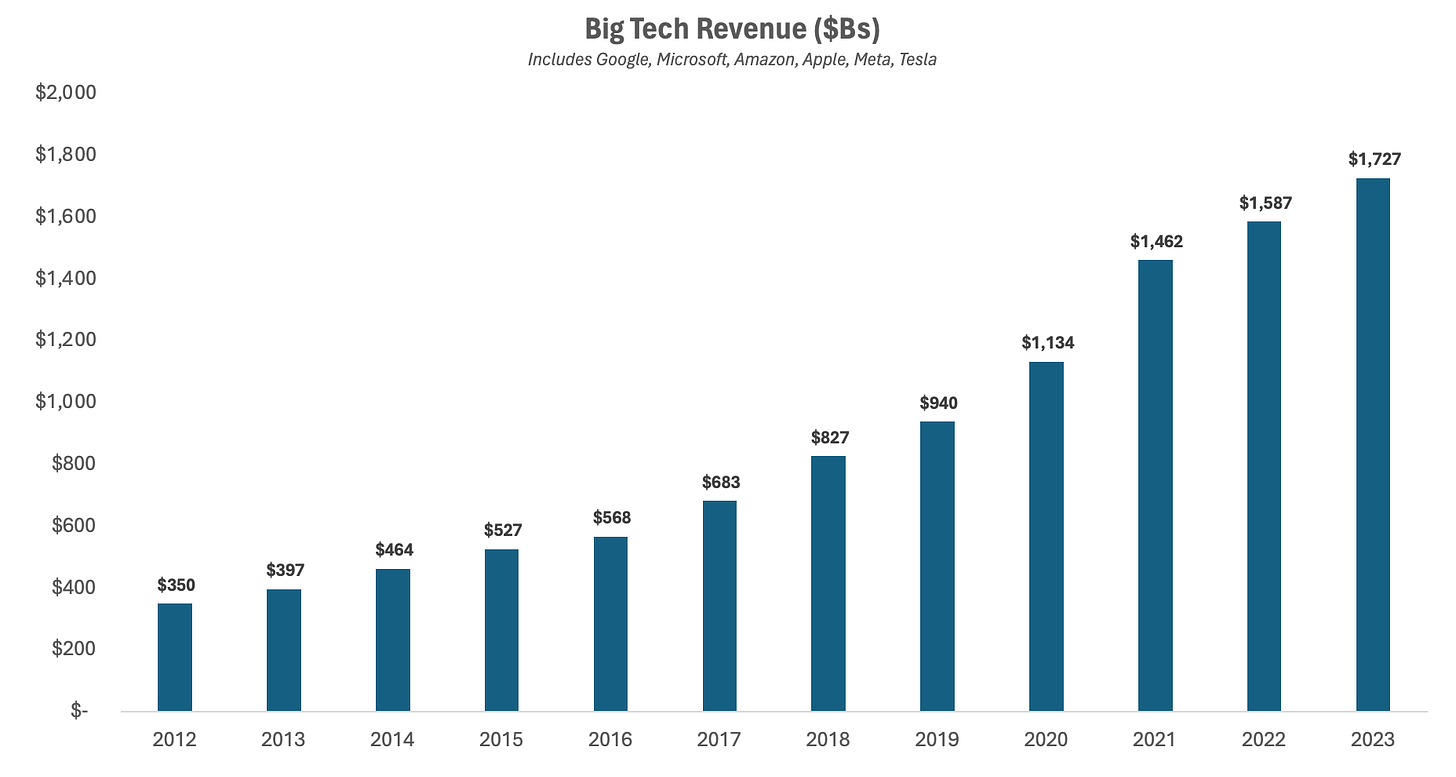

The odds of working with someone who has built technology at massive scale has historically been quite low. In large part because we're only just coming into massive scale. Even 10 years ago the largest tech companies were only seeing ~$200B of aggregate revenue. Today? North of $1 trillion dollars of revenue.

The number of people with experience building, scaling, and selling SaaS has only really taken off in the last 10 years or so. In one of the first investing roles I had, we did both later stage growth investments and small buyouts of software companies. The buyouts we did were often of old-school companies that we could help improve. The fact that even in 2016 one of our investment themes was "the company has made good progress in transitioning from on-prem to SaaS" is crazy to me.

The Process, People, & Playbooks of Tech

If you step back and look at the breadth of startup experience that people have today you'll start to appreciate two things. First, it's impressive the kinds of incredible experience people have now built up. And second, we're really just getting into the first generation of that experience being widespread.

There are countless examples of things that people couldn't have had much experience in because they're so new: cloud security, generative AI, transformer architecture, Kubernetes — all of these are ~10ish years old.

Here's just one example within product-led growth.

The Process: Product-Led Growth

Today product-led growth is one of peoples favorite business models to talk about. Tons of well-known companies claim it. Datadog, Stripe, Github, and Mailchimp. In September 2023, ~91% of companies planned to increase investment in product-led growth. Sales has progressed from being directed by CIOs to org-specific execs and today is being driven by the end-user.

PLG has really come into vogue over the last few years. Companies like Adobe or Shopify have been offering some of their products self-serve since the early 2000s. But effectively balancing bottom-up PLG and top-down sales hasn't been common until recently.

When you look at enterprise sales it has historically still been heavily account-based. Only within the last 10 years or so have you seen companies like Slack, Dropbox, and Twilio pioneer the balance between PLG and enterprise sales.

One of the best descriptions of this strategy evolution comes in a Stratechery interview from 2020 where Jeff Lawson, the former CEO of Twilio, is explaining how even the most product-led companies have to figure out sales sooner or later:

"I’ll tell you a story of how we came to invest quite a bit in sales. We now have a very large and very productive, fantastic salesforce. But for a long time, we struggled with understanding how much we should invest in sales. I was influenced by Mike and Scott at Atlassian because they always famously said, “Whatever you’re going to spend on sales, just put it into the product to make the product better. Anytime a customer needs to talk to a sales person, that’s a bug you have to go fix.”

Then you talk to them and you’re like, “So you guys hate salespeople.” They’re like, “Well, not really.” And I’m like, “Well, what do you mean? You don’t have any and you tell everyone how having salespeople is like the death of the business.” And they’re like, “Oh no, we have salespeople, we just call them something else. We just call them Support Specialists or Customer Success, or just some other name. But yeah, they’re basically doing sales.”

Great products do make people want to use them, absolutely, but relationships matter too. We’ve really evolved and innovated on this dual pronged approach of getting initial momentum with developers and then you follow through with a great sales process and that has allowed us to land larger and larger accounts."

As companies have started to figure out how to balance product-first building with a need for high-quality relationships they've had to train people who can walk that line. And now there are quite a few of them. You could say we're seeing the first generation of PLG-native talent coming into their own.

The People: Kyle Parrish; From Dropbox to Figma

Kyle Parrish started in one of the most traditional enterprise sales orgs: ADP. Big lumbering old-school software with massive teams dialing for dollars. As he was trying to find the kind of team and environment that would better resonate with him he got introduced to Dropbox. He joined in 2011 when the company was at around $30M of revenue.

You can definitely argue that Dropbox is one of the early pioneers in balancing PLG with enterprise sales. Kyle certainly does. “We were early on in 2011 at Dropbox in having this consumer freemium model that also had an enterprise play." From there he joined Figma as the first Head of Sales. "I was the only non-technical person in the company at the time." Where Dropbox was pioneering this balance between product and sales, Figma would go on to truly master it.

The Playbook: Figma's Approach

I'm always surprised to see how quickly something that was a novel hard-won idea at first becomes accepted as obvious fact. Today PLG feels like a no-brainer. From 2016 to 2022 the Forbes Cloud 100 went from being ~30% PLG companies to ~68%. But PLG wasn’t always so obvious.

When Kyle started at Figma in 2018 this hybrid approach of PLG with a "sales rep assist" was still relatively new. Kyle may not have been the only person in the world that could have built the sales motion that Figma has today, but he was certainly in that first generation. At Figma, they were playing with what Kyle had learned at Dropbox and how that worked with Figma's product. They were able to use the same kind of data that informed their product decisions (feature utilization, user engagement) and let that guide their sales process.

Today there are CRMs purpose built for PLG companies. They act at the intersection of product analytics and GTM automation. Those kinds of tools are getting built to replicate the hard-won lessons of the past few years influenced by these early PLG pioneers. That generation of people who wrote this playbook are just coming into their own as managers and leaders.

People who built the team of account managers at Slack, and worked with their first VP of Sales in 2016. Or the people who grew up as one of Atlassian's “enterprise advocates” who focused on getting large enterprise customers to more fully adopt Atlassian’s suite of products. These are the early training grounds whose best and brightest are becoming their own centers of gravity.

The Evolution of Startup Nodes

Product-led growth is just one example in an ocean of lessons learned by the collective startup community over the last 20 years. We've seen the evolution of SaaS, mobile, cloud infrastructure, payments, usage-based pricing, open-source models, and developer-first products. You could tell the “Kyle Parrish” story for any one of these trends and a hundred more.

There is a growing population of people that have learned the lessons of the last few decades through their experience building the greatest generation of technology companies in the history of mankind. And as those lessons get distilled to a broader group of people we no longer have to spend so much time reinventing the wheel. Progress comes out of learning from past experiences. And it comes more quickly when those lessons are effectively distributed.

Renata Quintini at Renegade Partners described it to me this way in 2022:

"Skills are different than mastery. Market opportunities are bigger. Capital is available. But some things that used to be a competitive advantage are table stakes today. There is power in creating a scaffolding [of best practices] because it's more than just people. There is value in preparation, rituals, and familiarity."

People who have spent years not just learning but inventing these playbooks and best-practices are nodes within the collective knowledge base around building technology. Just look at a sampling of some of the most impressive people within tech across payments, infrastructure, marketing, finance, and everything in-between.

Update: I made these graphics in early 2022. In February 2023, Alyssa became the CEO of the Square business within Block.

Update: Alex stepped down as the CMO of Datadog in December 2023 after a 10 year run!

If you met one of these people at a party and looked them up afterwards you would brag about it to your friends. And this is just a tiny sample. There are hundreds of these types of people. People who worked and struggled and whiteboarded and fought to create the models, and frameworks, and designs, and approaches that we all take for granted every day.

And next to them are thousands of people who were trained by them or grew up in the same organizations just waiting to demonstrate their own breakout ability.

The Renegades of Tech

Previously I’ve written about the unbundling of venture capital. There is a big universe of potential investors and it is growing all the time. Historically the focus has been on big monolithic brands and powerful kingdoms within venture. But the world is changing. The key idea for me as I explored that trend was just how long the long-tail is.

“There is a long-tail of super talented people who may not be the best investor for everyone, but for a specific group they'll be the perfect investor.”

The same is true in tech. For a long time we've looked at technology as the work of these genius Gods. Not a benevolent God, but the emotional Gods of the Greek Pantheon. Steve Jobs, the God of Beauty who would hurl desks and F-bombs at mere mortals. Elon Musk, the God of Lightning whose children are little furry dog coins. These characters that we build up to be larger than life (even when they sort of tank on SNL).

The internet allows people to more effectively distribute their creativity and find their niche audiences. That is the same force that is impacting venture as people look for humans that they can understand and relate to who offer products that perfectly fit their needs. We're seeing the same appreciation start to grow in tech. As important as the Elon Musks of the world are, people are starting to more fully appreciate the people behind the curtain, like Gwynne Shotwell.

Gwynne Shotwell is one of my heroes. The dreamers are important, but the world would make very little progress without the doers:

"Shotwell runs day-to-day operations and customer relationships [at SpaceX], but her official title might as well be rainmaker. She takes CEO Elon Musk’s seemingly outlandish ideas (and idealistic timelines) and makes them happen: Achievements include the successful launch of SpaceX’s powerful, reusable Falcon Heavy rocket."

Shotwell is exactly the kind of leader that I most enjoy learning from and working with. Whether it is someone like her who is already launching and landing rockets or a mid-level leader; a rising star learning the ropes and inventing the future, or even the newest PM who is so obviously sharp and ambitious enough to look to one day sit in Shotwell's seat.

Back in 2022 Jeff Burke at Replit described his experience to me this way:

“When I was at Cisco I remember talking to my manager and they kept talking about how they were happy to never go much higher than their current level. They asked me what I wanted in my career and I thought, ‘I want to be the CEO.’ That’s when I realized I was different than most of the people I worked with. I wasn’t prideful. But I had ambition.”

These are the people that build the future. No one who has been the visionary founder would disagree with the game-changing role these people play in turning that vision into reality. As the art of building technology companies has progressed and become more demystified it has become easier to see the people who make things happen. These are the people to watch.

Playing The Playbook Game: A Retrospective

There has been one important evolution in my thinking since first writing this piece in 2022. The more a space becomes professionalized, the more it can be gamed. The more you know the rules, the more you can break them. What is fascinating about the generation of entrepreneurs and investors that were most active from the early 2000s to ~2020 was that they were often inventing the way things were done.

That isn't as true today. Many of the companies are following fairly established playbooks. But the question is two fold: (1) how much arbitrage is left in known-knowns? And (2) how much more exposed to manipulation is a well-established playbook?

Unsustainable growth models are one of the prime examples of the sins of the last few decades. People built models that don't work so that they could scale, believing that at scale things will work out. But the reality is for most companies, that isn't the case. And now, skepticism is starting to set in. More investors, candidates, and customers are going to be more analytical in understanding the quality of a business's economic engine.

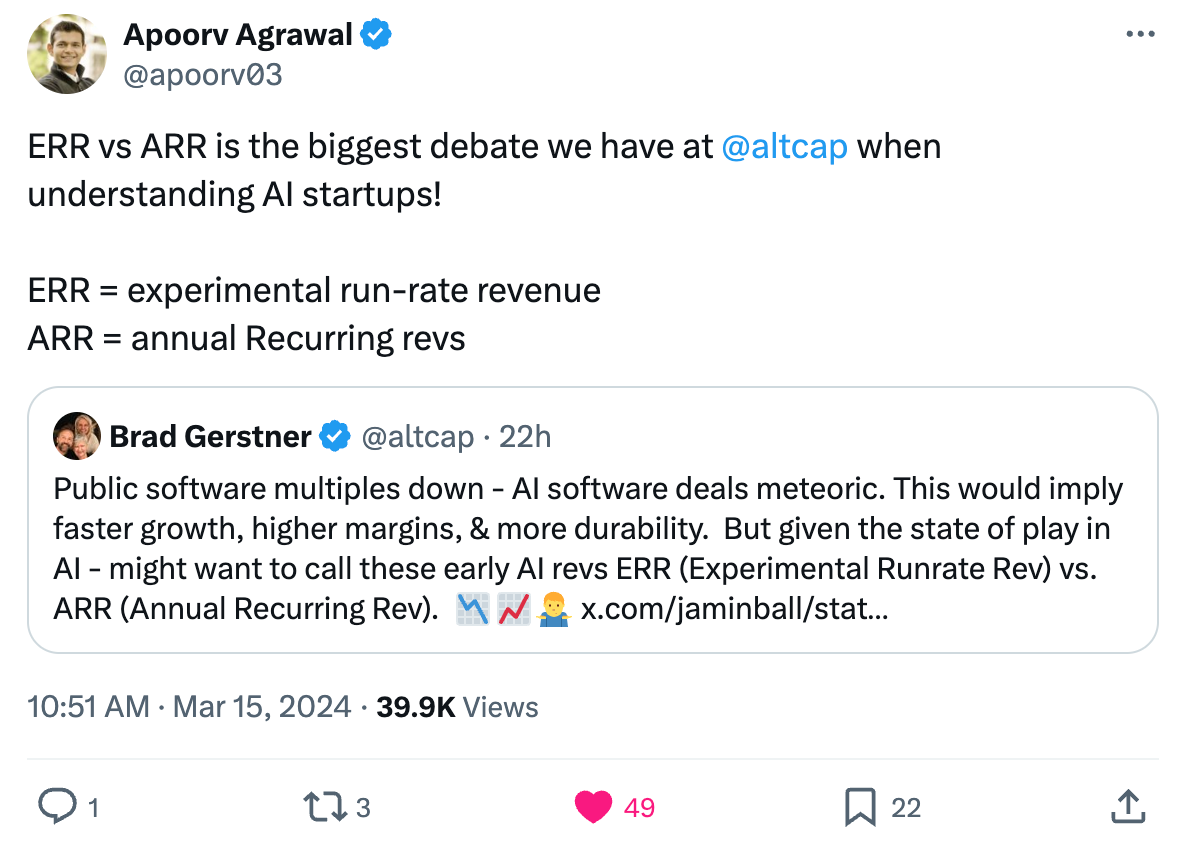

Instead of learning from past mistakes, many people will simply reframe those mistakes into new models of the same old sins. One example in the AI boom we're currently experiencing? "Experimental run-rate revenue."

People will frame massive revenue ramps as steady-state growth, when in reality, a huge swath of that revenue represents experimental budgets from excited customers trying to get their hands on AI. But the likelihood that these elevated levels of investment in AI capabilities remain in perpetuity is unlikely. What is more likely is that this is a function of AI companies that understand the narrative value of growth, and are able to articulate experimental revenue ramp as reality.

So a word of caution as we step back and appreciate the professionalization of startups. There is a spectrum that exists where playbooks can be transformative or manipulative. As the game becomes more well-known, people start playing on the weaknesses of the game itself. And that can leave people vulnerable.

So learn from the people, processes, and playbooks that have been explored. But don't turn them into dogma.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

I enjoy your writing, you seem level headed/ down to earth for a vc. Also quite funny to learn about err - what could go wrong, right?