Teamshares, Hold Co's, & Corporate Cities

A Model For Building Communities / Juntos / Cities / Holding Companies

This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I'm fascinated by an idea that I've never been able to put a word to. At different times that interest has manifested as a fascination with city building, urban development, communities, co-operatives, Juntos, holding companies, and conglomerates.

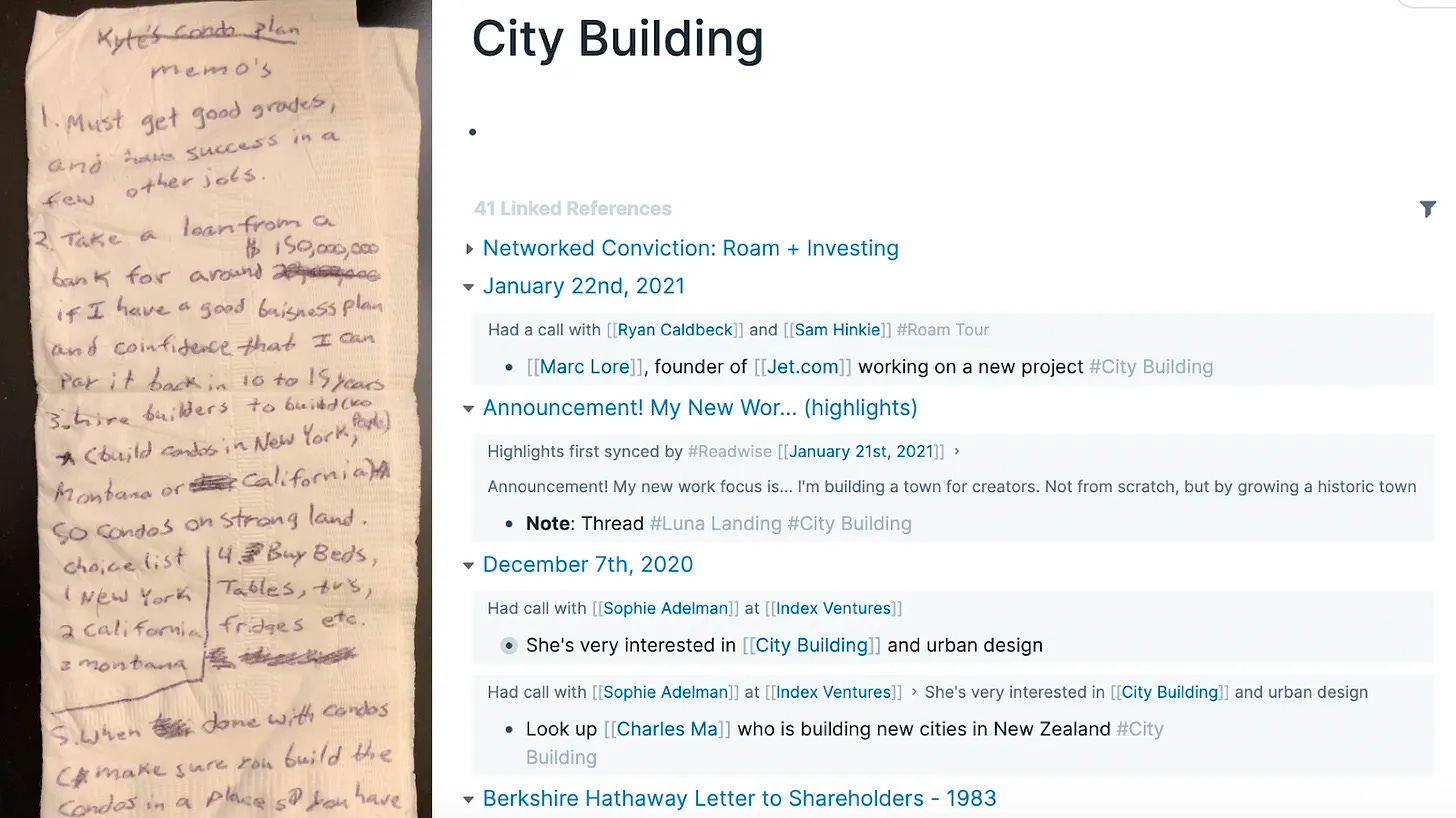

Early in my life I thought about city building. I had written a business plan on a napkin when I was about 12 years old that outlined how I would build a city shaped around a unified experience.

That same fascination with city building led me to spend a lot of time thinking about things like Walt Disney, and his original vision for EPCOT (which I've written about several times here, here, and here.) I was always looking for these examples of purpose-built communities.

In 2014, after I sold my first company I spent time at Cambridge where I did a Supervision Thesis sponsored by a faculty member. My original proposal revolved around this same idea. I described it, at the time, as a fascination with "the way people interact with the world around them."

Over time, my interest took shape in a fascination with holding companies. I loved studying Constellation Software, Berkshire Hathaway, and others. The kind of unified human experience I saw occurring in a city that was purpose built was always influenced by the why of a city. What is the economic driver of a collection of people? Holding companies felt like a more direct representation of those aligned economic drivers.

The more I understood the value that a central entity could create by having a common goal and a core competency, the more I started looking for those in different business models. In 2019, I found one that perfectly articulated what was most compelling to me about this type of model.

Introducing Teamshares

I got introduced to Michael Sutherland Brown, Alex Eu, and Kevin Shiiba when they were just getting started building Teamshares. The company's original thesis was built to address a key equation around economic opportunity:

Almost 50% of people in the US are employed by small businesses.

80% of businesses never sell. For small businesses, in particular, that's often because there is no one willing to buy them.

The vast majority of small business employees don't own any equity in the companies they help build.

When I met the folks at Teamshares, they had only bought 2 or 3 companies, mostly using some of the small venture funding they had raised. But the goal was to create more economic value for more people by enabling employee ownership at scale.

The TLDR on the business model: Teamshares buys small businesses with $1-10M of revenue in a mixture of equity and debt. They grant 10% ownership to the employees, and over time the employees can increase their ownership.

One of the firms I respect the most that has a very similar ethos of creating "buy and never have to sell" families of companies is Brent Beshore's Permanent Equity. In an interview with Permanent Equity's President, Emily Holdman, she described the conundrum that most small businesses face when it comes to their own longevity:

‘[Small business owners] have three options: We either need to figure out how to live forever; we need to to build an ESOP plan and implement it (which is an option, but has some onerous terms in association with it); or we’re going to have to shut down the business. And he’s like, ‘I don’t think I’m going to be immortal. I’m not going to figure that out. So basically I can do an ESOP or I’m going to need to figure out how to wind down this business.’

Solving the arduous process of becoming employee owned was Teamshares' original product; a Teamshares buyout if you will. Creating a mechanism that made it easier for owners to sell, and to do it in such a way that their employees would be capable of receiving and building ownership of the company over time.

Increasingly, people are appreciating that the more ownership people feel over the companies they help to build, the more performance improves. In a report on Carta, who has become an index on employee ownership, Tribe Capital makes this point:

"Without equity, it’s not possible to align incentives in a way that is attractive to highly skilled employees relative to other employment. Widely-owned equity is the mechanism by which entrepreneurship spreads from just the founder to the entire team of employees who devote substantial portions of their working life towards building something whose rewards they can take part in."

Fast forward to today, Teamshares recently announced how they've been doing. They've now extended employee ownership to "2,100 employee-owners at its 84 businesses. Their stock is worth $27 million, and they have earned more than $1 million in dividends."

In aggregate, Teamshares has $416M of revenue across its companies. A family of companies that extends across butcher shops, a notary service, an auto-repair shop, and much more. Their model is an intricate one that they've executed incredibly well over the last few years. But beyond the specifics of the Teamshares model, I wanted to articulate a bit more about why the model is so compelling to me.

The Holding Company Model

I had the privilege of angel investing in Teamshares back when we first met in 2019. I invested again when I got to Contrary. But Teamshares isn't the only time I've been exposed to this kind of model. In addition to investing in Teamshares (and holding a fair bit of Constellation Software stock), I've invested in or worked with organizations like Merit Holdings, Eads Bridge Holdings, and Sylva. Just this week I made my newest angel investment in Workweek that has a very similar model albeit more of a build vs. buy approach to the members of their family of businesses.

Now, granted, all of these businesses have unique models and approaches. Some are more similar to funds, others are more traditional holding companies, and others are somewhere in the middle. But there are some unifying characteristics that make these models powerful.

A Shared Purpose

If I look back on the original manifestations of my interest in "the way people interact with the world around them," I realized that whether you're building a city, a Junto, or a holding company, there is always a unifying force. The feeling of marching in the same direction.

For some, that can be as simple as being an exceptional business. Berkshire Hathaway doesn't have a moral litmus test they apply to the companies they buy into. They simply ask "is this an exceptional company?" For others, quality isn't at the top of the list per se. Constellation Software is dogmatically focused on the purpose of serving niche verticals with sticky software. They don't have to be exceptional businesses because the value of Constellations "conglomeration" comes from quantity, not necessarily quality.

Any model that is looking to build long-term exposure to a basket of assets is dependent on the quality of its latest addition because of the way it will dictate the quality of future additions. This is most true of holding companies because they typically buy, and rarely sell.

But the same could be said of venture funds. Most VCs think portfolio theory protects them from their losers. But the reality is, if I invest in one WeWork or one Hopin or one FTX, it actually has an impact on my decision making, and my business building muscle. The more exposure I get to negative data points, the more my overall data set becomes corrupted. Whether I acknowledge it or not. Whether I even realize it or not.

A Core Competency

Knowing what "good" is to you is the shared purpose of any holding company model. But a more deliberate question is how do you structure your business around a core competency? What are you uniquely good at?

In a report on Constellation Software, Speedwell Research explains the way Constellation defines their core competency:

“Given that they are acquiring so many small companies, having multiple “capital allocators” who can find acquisition opportunities and deploy capital is critical, and actually at the heart of their success. When asked about Constellation’s philosophy on management, Mark Leonard often repeats a Buffett quip of 'delegation to the point of abdication'."

Constellation Software has ~300 employees (at least at the HoldCo level). Berkshire Hathaway has like... 8. But that ties directly into core competencies. Constellation prides itself on being uniquely good at having a replicable, quantity-driven playbook. They need as many "capital allocators" as they can because capital allocation along their playbook is what they're uniquely good at. Berkshire Hathaway, on the other hand, is much more in the camp of "a few good decisions." In his 2022 annual letter, Buffett says as much:

"Our satisfactory results have been the product of about a dozen truly good decisions – that would be about one every five years."

So for them, having more people would actually be counterproductive within their core competency. Defining what you're good at, where you create value, and how you can ensure that the engine around your business does the most to maximize your core competency—thats a big part of the magic!

Commoditize Your Complement

There is a widely used concept that explains competitive advantage called "commoditizing your complement." Here's one explanation:

"Companies seek to secure a chokepoint or quasi-monopoly in products composed of many necessary & sufficient layers by dominating one layer while fostering so much competition in another layer above or below its layer that no competing monopolist can emerge, prices are driven down to marginal costs elsewhere in the stack, total price drops & increases demand, and the majority of the consumer surplus of the final product can be diverted to the quasi-monopolist."

In holding companies, I've seen a slightly adjusted version of this framework. Once an aggregator has identified their core competency, there is value in commoditizing the rest of the process so that you can focus as much as possible on your core competency.

In the case of Constellation Software, consider their core competency of capital allocation in line with their playbook. They're so good at following a specific playbook, that they almost don't want out-of-the-box thinkers; they want people that can execute in line with the playbook.

But what about internal initiatives? Part of the typical value creation cycle for any business isn't just acquiring new businesses, but its also investing in new initiatives within existing business lines. But in that same Speedwell report on Constellation, they found that those internal initiatives took them away from their core competency:

"IRR on internal initiatives by and large couldn’t match what they generated on acquisitions and thus internal capital allocated to initiatives continued to be driven lower."

As a result, most holding companies are better off understanding their core competency—what they're uniquely good at—and working to commoditize every other possible part of the process to avoid any distractions.

What About Venture Scale?

One of the biggest pushbacks these types of companies get is whether or not they are "venture scale." This question is, like many in the venture world, one of relativism. Its all a function of valuation. One company that I liked conceptually within this model was Opendoor (heck I even liked WeWork for the same reasons, but they just got too irresponsibly massive in their ambitions without the underlying business to back it up).

Opendoor is, I think, a good example of an interesting business that isn't worth what its ambitions wanted it to be worth. So one function of venture scale can be determined based on the valuation relative to traction and business model potential.

WeWork could still be an exceptional business. But its loaded with so much insurmountable debt, that its now at risk as a going concern with a market cap of $262M.

The broader question: take a business whose primary economic model is to deploy capital in pursuit of aggregated assets that increase in value; can that be a multi-billion dollar business? Yes.

Whether its holding companies, like Constellation, Loews Corp, TransDigm, or asset allocators, like Blackstone, Apollo, or Ares. There are a number of case studies to point to of the potential size of these outcomes.

Most of these firms are generating billions in revenue too, so if a company's valuation becomes outrageous relative to traction, then no. It can be a terrible investment. But assuming the valuation remains commensurate with the potential of the business, there's no reason it can't be a good outcome.

Other investors express discomfort with the model, whether its holding assets, deploying capital, or leveraging debt. Those aren't what venture backed businesses do. Unless you count SpaceX, which is the most valuable private company in the US, who ✅ holds assets, ✅ deploys capital, and ✅ leverages debt.

Now, if you're uncomfortable with the business model, that's fine. Everyone has a "too hard" pile. But to deride the model as "not capable of venture scale" is inaccurate. More and more, businesses are proving that they are capable of complexity.

Businesses like WeWork and FTX take that complexity, and weaponize it into a smokescreen of hype and hubris. But other businesses, like SpaceX or Teamshares, have been able to acknowledge that complexity, and build in spite of it. In fact, most of those complex businesses would argue that the complexity of their model is what engenders discipline in their companies. They have to be vastly more aware of their complexity than the typical SaaS business.

So embrace the complexity. Or don't. But as for me, and my house? We will continue to invest in holding companies.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Listened to StrictlyVC podcast and was very impressed:

"Connie: And so there's nothing on your roadmap that includes helping your companies become PE targets down the road?

Michael Sutherland Brown: No, we actually make a very devout customer promise that our companies will become 80% employee owned and will never be for sale again.

Connie: Wow, that's really interesting!"

Agreed!

A Startup That ls Buying Up Mom-and- Pop Shops by StrictlyVC

https://open.spotify.com/episode/5MClOrfA8egSzMyF2fSeNS?si=6aCPn4IlQzusZZlXE_khPw

fascinating piece 📝