This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Quick Disclosure: Views expressed in this post are my own and not the views of Contrary LLC or any affiliate. None of the content should be construed or relied upon in any manner as investment, legal, tax, or other advice. You should consult your own advisers as to these matters. Certain information has been obtained from third party sources and has not been independently verified. See https://contrary.com/legal for additional important information.

Telling your kids about Santa Claus is such a tricky minefield. Is it fun pretending Santa is real? Sure. But are you lying to your kids? Oh, most definitely. And kids are so easy to trick. So easy. It's crazy. The plausibility of the tooth fairy, Santa Claus, all of it just slips right under the radar. I have three kids, ages 6, 3, and 1 so they're at various levels of "trickability." (Side note: The 1 year old is the hardest to trick. I say "look over there, a unicorn" and she just drools 🤷)

One of the reasons kids are so easy to trick? They want to believe in things. They love the idea of magic and superheroes. They want that world to exist. But being a parent sometimes feels like you only have two jobs: (1) feed them, and (2) be the one to break the news that the world can be a really sucky place sometimes.

Optimism is such a drug. People want so bad for the best case scenario to be true. We, too, are so trickable. For a species that had the majority of our "coming of age" years in a time when the life expectancy was 20-25 years and we were hunted more often than the hunter, it's surprising how optimistic we've been able to remain.

This is the other side of the storytelling coin that I find myself talking about so often. If you end up believing enough stories that aren't true, or getting overwhelmed with how often stories turn out to be a huge bummer, optimism becomes increasingly more difficult to muster.

Cash App: Too Good To Be True?

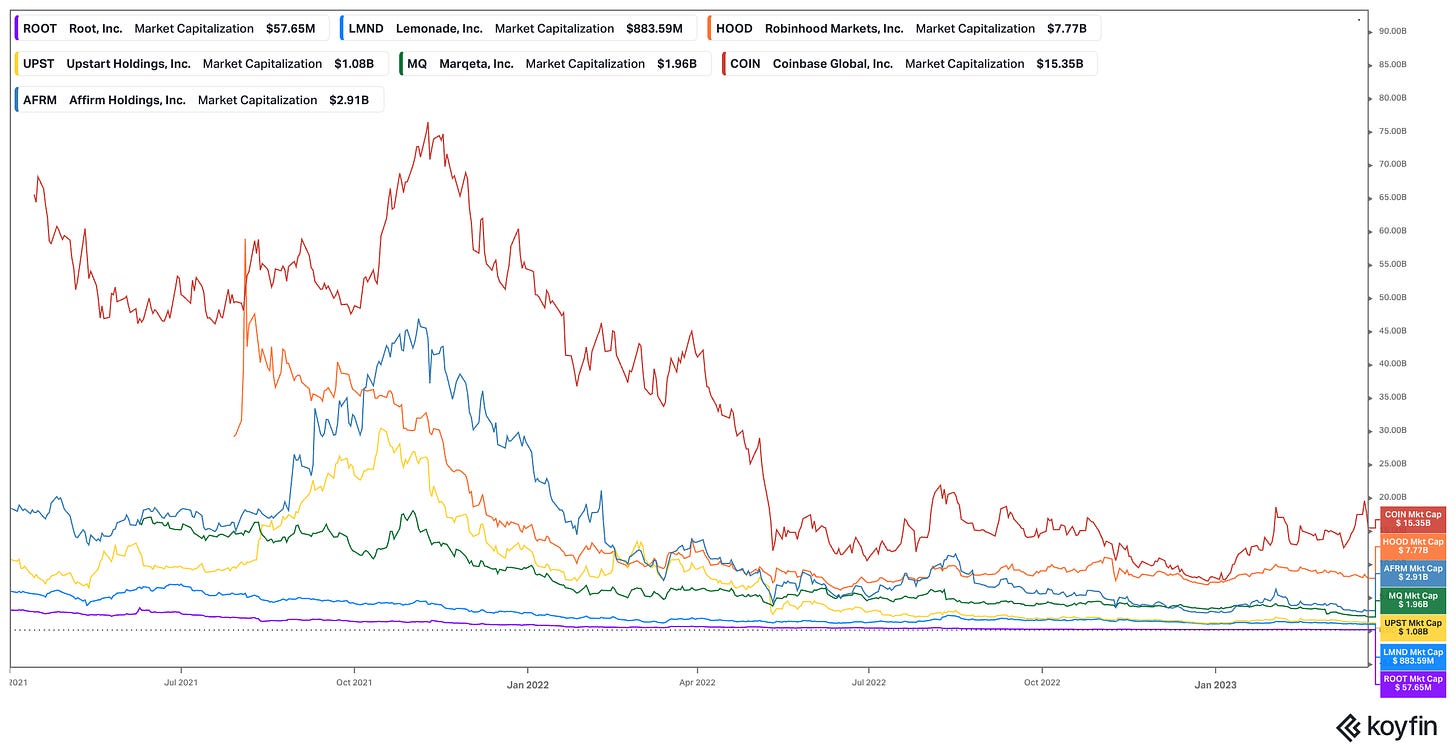

This week has been a real humdinger for bummers. But let's start with the one that had the most impact on me mentally. Already, I couldn't help but notice that fintech has had a... rough couple of months. Where companies like Robinhood, Coinbase, and Affirm used to be worth $30-40B+ each, in a basket of recently IPO'ed fintech companies the aggregate value isn't even worth $30B.

Block (the artist formerly known as Square) has been one of the bastions of the fintech world, held up as an example of success where most others stumble. Then yesterday, Block hit a bit of a Hindenburg moment. A short seller firm (appropriately named Hindenburg Research) published a report on the company.

In it, they characterized Block in a not-so-great light. In Hindenburg's words, "the magic behind [Block] has not been innovation, but its willingness to mislead investors, facilitate fraud, avoid regulation & dress up predatory products as revolutionary tech." As a result (at least in part), Block saw $10B of market cap get wiped out.

Now, it's important to note that I don't have any inside information or perspective that would make me an informed commentator on Block. Hindenburg Research also has an obvious bias: their business model is to short the stock of companies they believe to be engaging in fraudulent behavior, and then profiting when their reports drive the company's stock price down.

Some context. In September 2020, Hindenburg published a report on EV maker, Nikola, which turned out to be pretty accurate and led to an SEC investigation into the company's executives, and had dramatic effects on the company's stock price. So they're not usually just throwing baseless accusations.

One of the strongest arguments among bulls for Block has been the extraordinary performance of a specific product: Cash App. The P2P money transfer app has grown dramatically over the last few years, even becoming a cultural phenomenon.

One of the most aggressive accusations the report makes against Block is that much of that growth was created artificially, with potentially as high as 40-75% of accounts being "fake, involved in fraud, or duplicates." The report further claims the company has basically ignored the majority of KYC / AML checks, which have made Cash App the go-to option for committing crime.

The report feels well-researched and thoroughly troubling. Block's only response thus far has been to deny, and threaten legal action against Hindenburg Research. Not the most reassuring move.

And I'm not going to lie, the report really bummed me out. Honestly, I hope it's not true. I hope that Block is the innovative fintech company we all hold it up as, and not a case of cutting corners to maintain exponential growth by ignoring widely accepted safety parameters. But this story wasn't the only one that bummed me out this week.

Weaving Tales of Woe In Tech

Like most of the tech world, I also tuned in to the TikTok hearings in Congress where the CEO of TikTok was uniquely and uniformly skewered by American politicians from both political parties. The ups and downs of the hearing are disheartening for a number of reasons.

The growing conflict with the authoritarian government in China, the threat of technological imbalance in a potential global conflict (as displayed in future-focused "historical" fiction books like 2034), the mental health crisis among young people (including increasing rates of suicide), and so, so much more. So many bummers. Mike Solana did a great job live tweeting the hearings with his own special flavor.

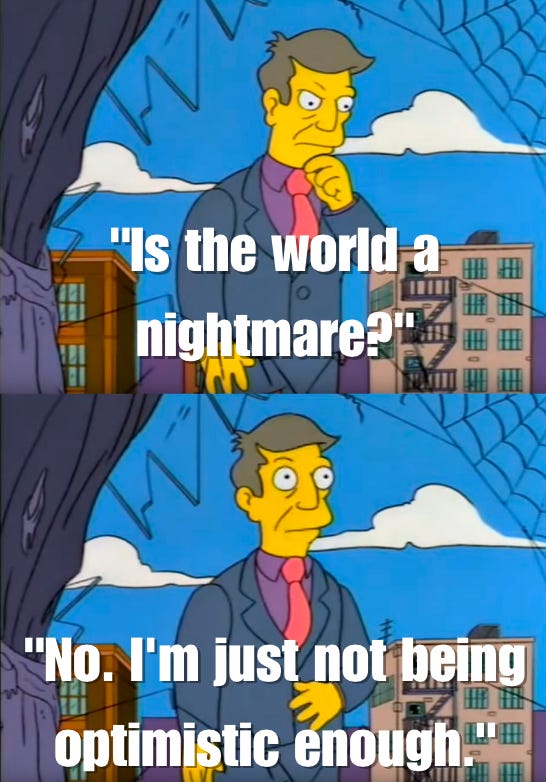

Two things happened to my mood yesterday: (1) I got really bummed, and (2) I let myself spiral into all sorts of over-simplification and logical fallacies. But the bummers just kept coming to mind.

"Where have all the good companies gone?" I asked myself that question over and over again.

With the Block fiasco, you start to question a lot of the validity of much of the fintech movement over the last few years. Robinhood is effectively invasive gambling. Root and Lemonade are just worse alternatives for insurance companies.

What about TikTok? That leads you down a rabbit hole of the nightmares of social media writ large. Whether its the intense neuroscientific programming we saw explained in documentary form, or the insane content moderation efforts that have pushed content moderators to legitimate cases of PTSD, and even suicide.

Then there are the classic examples of companies that we all try and squint to not think about how they tick, whether it's Apple's sweat shops or Tesla's cobalt mines.

You also have businesses that may just not be great businesses. Netflix's fundamentals. Meta's need for a return to fundamentals, and a decade of efficiency after burning $13B pursuing the metaverse.

Amazon? Exploiting workers. Berkshire? Hawking sugar water and sugar sugar. Saudi Aramco? Get out of here. Purdue? Fueling the opioid epidemic.

You see what I mean? Spiraling. So what pulled me out?

Optimizing Your Optimism

As easy as it is to criticize social media, it's also the exact thing that helped me get some perspective on what started out as not a great morning. I started messaging some of my favorite Twitter friends who think about a lot of these same questions. And I was reminded of a couple important realities:

Businesses are fundamentally problem solving engines

Believing the negatives outweigh the positives of technological progress is a position for inconsiderate people in privilege

Optimism and pessimism are not states of being; they're choices to be used for specific purposes

Problem Solving Engines

Why do I love studying businesses so much? Because they are fundamentally economic engines for taking in inputs, and attempting to maximize outputs. Are they always effective at taking inputs? No. Are the outputs always desirable? Definitely not.

But they are the best mechanism we have come up with thus far for producing innovation, progress, and problem-solving. No government, no think tank, no agency, no co-op, no secret underground illuminati has ever been more effective than the collective effort of the businesses of the world.

I've written before about the importance of understanding these economic engine behind any business:

"Every company will eventually have to answer for the intricacies of their engine, for better or for worse. The most important concept to take away is how every investor can do a better job of thinking about each company in terms of the economic engine that they're building.

There is also a lot of first principles thinking that you can apply to understand what an engine might look like at scale. And throughout the company-building process there is always a need to dream the dream, and tell the story. But analyzing a company with an economic engine that is starting to turn is a metrics-driven, first-principles process that more people need to do. And the people who are doing it need to always look for ways to do it better."

If Netflix has crappy fundamentals? Then it should be punished by public markets. But that doesn't negate the massive impact they had on kicking off the streaming era. Did that lead to more competitors, more bundles of offerings? Sure. But that's competition, and competition is good for consumers, which pushes people to create better offerings. If Netflix sucks, then let capitalism punish it. Because that's an incredible motivator to drive quality.

Believing that companies CAN be incredible, and then holding them to that bar is important. Maybe Hindenburg Research just hates Block, and wants to make a boatload of money shorting the stock. But if they're right about what the company is doing? That's a good thing for them to call out. People being willing to both dream the dream AND criticize the dreamers represent a much healthier ecosystem than unchecked dreamers or lazy pessimists.

Progress From A Privileged Point of View

One of the more humbling responses to my question, "where have all the good businesses gone?" came from my friends who know what its like to live in much poorer countries with dramatically less opportunity than we have in the U.S., and where technological advancement may not be as taken for granted as it is here.

My good friend, Mostly Borrowed Ideas, put it the most succinctly in a way that really pushed me to get outside my privilege bubble:

"I strongly disagree with social media’s characterization in the West. It is NOT digital crack. Some users may struggle with it but by and large society is a large beneficiary of social media. Connecting the whole world is an incredible feat. It is super important to unlock talent across the world. I think most people in the West underestimate the power of the internet in general because they are lucky to be born in the developed part of the world.

And while their problems/struggles are very much real, they are indeed "first world problems" to the vast majority of the world. So much complaints about an ad-based model without realizing this is why the random guy in Bangladesh (where I'm from) can access vast amount of knowledge/connection on the internet. Social media has made it essentially free to connect with anyone I know anywhere in the world."

This conversation was also a timely one, given a recent conversation that took place online around a post from Jonathan Haidt where he blamed the rise of social media for the deterioration of mental health among young people. But there have been some great criticisms of that idea, mostly pointing to the fact that a culture of meritocracy and achievement were pushing young people towards mental health issues long before social media existed.

In addition to that, one major criticism of social media is its advertising business model that turns the consumers into the product. But the conversation around Haidt's article allowed people to expose that criticism as the privileged position that it is.

The reality? Technological progress has been a net positive for the entire world. People often point to the idea that most businesses revolve around one of the 7 deadly sins. But social media didn't create pride, or envy, or even loneliness or wrath. The worst things about the internet, social media, and technology, are largely things based, not in technology itself, but in human nature.

Technology may have amplified many of those basest instincts we have, but those exist with or without that amplification if we let them. To spit on the power of technological progress in favor of "dignified" Luddism is to parade the privilege of your upbringing for everyone to see in quintessential virtue signaling, while disregarding the dramatic positives technology has had globally.

Solving those problems, and lifting us away from the “worst possible version” of ourselves is a worthy goal. But humanity’s problems can’t be something we just lay at the feet of technology. We could do more looking inside ourselves.

I’ve always liked this quote from Confucius about the importance of individual accountability:

“To put the world in order, we must first put the nation in order; to put the nation in order, we must first put the family in order; to put the family in order; we must first cultivate our personal life; we must first set our hearts right.”

Putting Optimism & Pessimism To Work

Finally, let's return to that age-old drug: optimism. It can often feel like choosing to be optimistic is just choosing to be the greater fool. Closing your eyes, and letting the world take advantage of you.

Geoff Lewis, a not-VC at Bedrock, shared a great framework yesterday around optimism vs. pessimism that has been updated to adjust for the current macroeconomic environment. He also credited Patrick Collison for helping to push his thinking:

Geoff in 2021: "I have noticed this juxtaposition of a generalized pessimism with a specific optimism about the company and the things within the locus of control."

Patrick Collison in 2023: "At Stripe, we want to be micro pessimists and macro optimists."

Geoff in 2023: "In March 2023, I think Patrick and I were only half-right. Now, the best stance to take is to be both micro pessimistic and macro pessimistic. The value in taking a pessimistic stance is that it imbues you with the agency to do something about all the risks to your business. And so in a world where the macro is stable, you want to focus on the micro of your own organization. In a world where the macro is unstable, by being pessimistic about the macro you can take agency over developing contingency plans. The era of techno-optimism is over. That doesn't mean there's not going to be phenomenally great technologies that are going to be good for the world. But it does mean that I believe the entrepreneurs building those companies are going to have a pretty pessimistic stance on both the micro and the macro. But, they're also going to take agency over it, and do whatever they can to survive."

In other words? "Prepare for the worst, and expect the best to come from it."

In reality, I think that this view is still bent towards optimism. If you didn't believe you could have agency and impact the outcomes of your business, you wouldn't do anything in the first place. Believing that anything is changeable is, by nature, optimistic. Just like "the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice," so too is the arc of human development long, but it bends towards progress.

My go-to source of optimism is Packy McCormick. He's done a great job of keeping a stiff upper lip through hell and high water. In a recent piece called "The Happiness Hypothesis," he laid out the case for why technology has the purpose of creating more "potential for happiness":

"The purpose of technology is to increase the potential for happiness, but most people don’t feel like technology makes them much happier. In fact, in the short-term, technology can make many feel unhappy — the gains from new technologies are unevenly distributed at the beginning, and ever-increasing efficiency creates a meaning vacuum that needs to be filled.

Of course, some things do succeed. But by the time they’ve reached enough scale to make a meaningful dent on the potential for human happiness, those humans don’t get much happiness out of them. Once we get used to the internet, we take it for granted. Once we’ve had all of the world’s music in our pockets for a couple days, we complain about Spotify’s new UX or how buggy video podcasts can be.

If people who work in and invest in tech are definitionally the people who most believe that technology is good for humanity, it’s on us to work constructively with politicians, and more importantly, to deliver products so useful to average people that politicians can’t find an easy scapegoat in the tech industry. As technology enables longer lives and more free time and more material abundance, it leaves an equal and opposite opportunity for humans to turn that potential happiness into real happiness."

It's not enough to say "progress = happiness." There are a lot of components missing that should make you capable of stepping back and being critically pessimistic about your potential optimism.

I feel the same way about religion. I'm Christian, but I get incredibly bothered by "mainstream Christianity." People who just dogmatically refuse to believe any non-Christians can be happy, or have doctrine or culture that is valuable, or that anything that is remotely misaligned from your beliefs is therefore heresy, punishable by ostracism. Is your faith really based on the earth being 6,000 years old? Or can you abstract to a more first principles approach?

The same is true of tech. The two opposing ideas that every person working in technology needs to maintain are (1) technological progress is good, (2) technological progress brings with it a lot of social and moral dilemmas that shouldn't just be swept under the rug.

What Does This Mean For Venture?

There's so much more that I'd like to unpack around these ideas at some point in the future. The idea that pessimism always sounds smarter than optimism, and that it's so much easier to say no, than yes. The general lack of awareness among people working in tech as far as how society, more broadly, views technological progress. The bent of mainstream company building and company funding is often towards incremental innovation.

But I think the key takeaway for me came from another conversation with a friend of mine. In it, I found myself asking this question: "Would you rather build towards something you're proud of, even if you knew you wouldn't make a lot of money doing it? Or would you rather build towards something you may not be proud of, but you're sure to make a lot of money?" In my opinion, the world of building and investing in tech companies could use more folks who don't believe the ends justify the means.

In shows like Breaking Bad, you have justifications for a myriad of violence supported by the idea that those actions have led to "a business big enough that it could be listed on the NASDAQ." If Block is removing all guardrails, making exponential growth possible by empowering human trafficking, drug dealing, and murder… does the exceptional growth and "value to shareholders" justify that?

Even outside the realms of the illegal; does the creation of exceptional cash and returns justify businesses that create limited happiness? Or produce artificial happiness that is short-term compelling, and long-term detrimental? Or even just products that create limited value in people's lives? Do those businesses maximize the potential that we all have to create exceptional things?

I don't buy in to the criticism that "the world doesn't need another B2B SaaS app." Instead, I believe that more companies, more venture firms, more entrepreneurs need to justify their beliefs and actions. Why do we do the things we do? And we can all do a better job of holding each other accountable for those answers.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Love the breaking bad reference