This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

A few weeks ago, I wrote about ~20 different ideas that I've been thinking about touching on this year. Rather than start to randomly prioritize, I thought I'd ask my readers (you) what you were most interested in. The Puritans of Venture Capital was the top pick. Second up? This one:

Books 2.0: Books are the LEAST effective way for information transfer, yet they remain one of the most popular. There's got to be a better way to design systems of information.

Let's dig into it.

Have you ever seen something so cute, you can't stand it? The cuteness elicits an overwhelming physical response. Babies, puppies, meerkats. Whatever floats your boat. Just the cutest thing in the world? So cute that you can't help but feeling like you just want to eat it! "I could just eat you up" (read in your most babyish grandma voice).

Well, it turns out that feeling actually has a name: cute aggression. And not just a name, but several pieces of academic literature unpacking the phenomenon.

But I think for a lot of people, it isn't just the intake of cute imagery that creates a physical response in us. How many times have you seen a movie where you almost can't speak afterwards? Or watched a play in a football game that leaves your jaw agape? Or felt the rush of adrenaline from dropping out of an airplane (I assume with a parachute, though to each their own) that made you feel inhuman?

What about reading a book that shakes you to your core? Sometimes, sure, maybe you even want to eat it. It's just so all-encompassing. Something about that book impacted every aspect of you.

I keep track of those types of experiences on my personal website. Ryan Holiday calls them "quake books." The fact that any book can have that effect on people speaks volumes to the power of the medium. But, by and large, books are one of the most ineffective forms of information communication and ingestion.

Putting Books on Trial

The definitive piece that really cemented this question in my mind comes from Andy Matuschak, an applied researcher focused on education, who previously worked on education at Apple and Khan Academy. The piece is simply called, "Why books don't work." His core thesis?

"As a medium, books are surprisingly bad at conveying knowledge, and readers mostly don’t realize it... Books don’t work for the same reason that lectures don’t work: neither medium has any explicit theory of how people actually learn things, and as a result, both mediums accidentally (and mostly invisibly) evolved around a theory that’s plainly false."

Andy's review of the literature exposed me to a lot of frameworks I've used to question the quality of my mediums for learning. But no disrespect to Andy, but for as successfully as he unpacks the problem, he doesn't give much of a solution. He says so himself:

"How might we design mediums which do the job of a non-fiction book—but which actually work reliably? I’m afraid that’s a research question—probably for several lifetimes of research—not something I can directly answer in these brief notes."

What I've tried to do is unpack a bunch of interconnected ideas about the history of books, and why they're so very resilient, and more broadly how we learn, methods for doing it better, and then (for fun) looking at some of the "dream the dream" scenarios for what Books 2.0 could look like.

The Investor's Perspective

Before I dive in to the myriad of pools I've gone fishing in for perspective on this topic, I wanted to pause and reflect. Why, in a blog called Investing 101, is an exploration of books as an educational medium relevant?

First, investing in its purest form is an exercise of information inputs and outputs.

More broadly, I love this other quote from Andy Matuschak:

"I spend a lot of time thinking about why knowledge workers don't spend very much time thinking about knowledge work."

A more investing-specific version of this idea comes from Josh Kopelman at First Round in a quote I've written about before:

"So many investing teams spend a LOT of time making each investment decision -- but so little time thinking about the frameworks / rubrics / systems that they use to guide their decision making process."

Investing can, in many instances, be boiled down simply to taking in information on people, markets, products, problem statements, supply chains, technical capabilities, etc. and then making a decision (and backing that decision up with cash). But given the fact that information ingestion is a huge swath of the job, it's pretty surprising we don't spend much time thinking about how to get better at that part of the job.

Second, the implications of AI, in particular, are going to have a dramatic impact on our relationship in knowledge. As I'm exploring, investing in, and watching the evolution of things like large language models, I can't help but be struck with the need to better understand the medium of how people take in information.

The Foundations of Books

A Love Letter To Books

A core principle of my writing is that if you truly love something, you're willing to criticize it. I've done that over (and over and over) with venture capital. The same is true of books. For those of us who genuinely love reading, there are countless quotes that romantically register our feelings about reading, and the feeling of sitting down in a coffee shop with a good book. Just a few of my favorites:

"I cannot remember the books I've read any more than the meals I have eaten; even so, they have made me.” (Ralph Waldo Emerson)

"What an astonishing thing a book is. It’s a flat object made from a tree with flexible parts on which are imprinted lots of funny dark squiggles. But one glance at it and you’re inside the mind of another person, maybe somebody dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, an author is speaking clearly and silently inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people who never knew each other, citizens of distant epochs. Books break the shackles of time. A book is proof that humans are capable of working magic." (Carl Sagan)

“Books are the carriers of civilization. Without books, history is silent, literature dumb, science crippled, thought and speculation at a standstill. Without books, the development of civilization would have been impossible. They are engines of change (as the poet said), windows on the world and lighthouses erected in the sea of time. They are companions, teachers, magicians, bankers of the treasures of the mind. Books are humanity in print." (Barbara Tuchman)

Amidst that romantic vibe, it can feel off-putting to criticize books as an educational medium when lots of people view them more as spiritual relics. One pushback to a universal criticism of the effectiveness of all books could be the separation of books into categories, whether it be fact vs. fiction or pleasure vs. productivity reading. But that, for me, boils down to a first principle of the "job to be done."

Storytelling vs. Reality-telling

Andy's piece touches on some of these nuances:

"I’m not suggesting that all those hours [reading books] were wasted. Many readers enjoyed reading those books. That’s wonderful! Certainly most readers absorbed something, however ineffable: points of view, ways of thinking, norms, inspiration, and so on. Indeed, for many books (and in particular most fiction), these effects are the point."

I think most books have elements of two core activities: (1) storytelling, and (2) reality-telling. And no, those don't map 1:1 across fiction vs. non-fiction. There are plenty of fiction books that will teach you more about reality than just about anything beyond lived experience. Meanwhile, arguably the majority of non-fiction is about as far removed from reality as The Time Bandits.

I recognize everyone is free to have whatever experience with books they'd like, and to be as satisfied as they so choose with the experience. But if the two core jobs you're looking for books, fiction and non-fiction alike, to solve is to immerse you in either storytelling or reality-telling, then there is lots of room for improvement.

Why are books so gosh darn resilient?

From the invention of movable type by Gutenberg in 1439, books started getting going. It took ~400 years to hit a billion printed books.

In simplest terms, "books were cheaper, less cumbersome, and more easily replaced than scrolls and the early forms of books." So, for hundreds of years the medium remained the primary attempts at information transmission. But I'd argue books were more effective as mechanisms for information storage, rather than transmission.

And modernity seems to have proven that as other forms of media have taken up far more of our attention. A mixture of dopamine addictions, time limitations, and cost structures have pushed in a new slew of mediums vying for our top choice for information transmission.

Our Relationship With Books

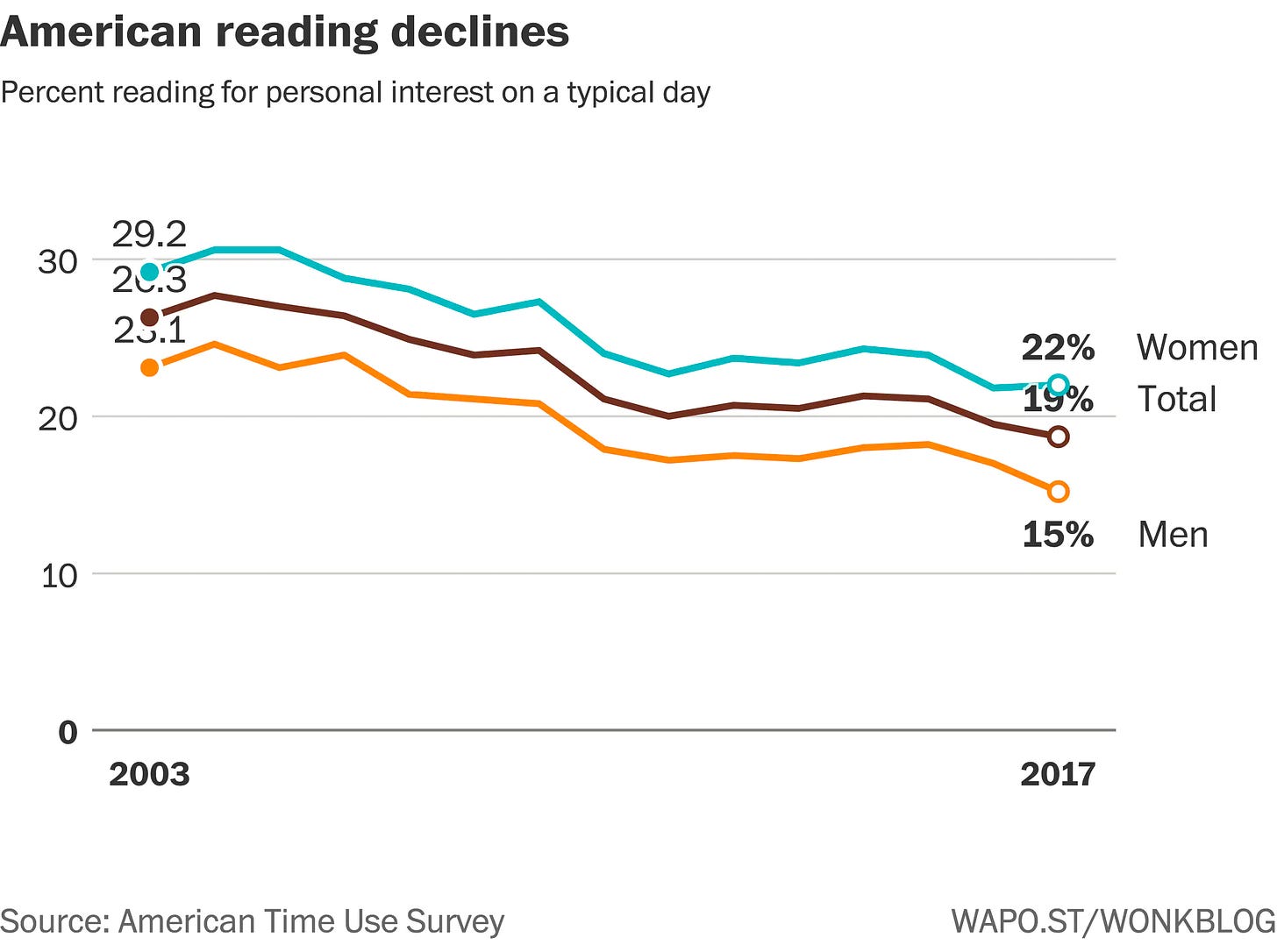

People are, definitively, reading fewer books and spending less time, in general, reading books. The "American Time Use Survey" has collected 15+ years of data, shedding light on what people are doing with their time. Across gender, race, socioeconomic status, etc. Everyone is consistently reading less.

While reading has been in steady decline, it was quickly overtaken as soon as television hit its heyday. The first television broadcast was in 1927, but TV really took off in the 50s.

From 1950 to 1959, the percentage of American households with a television set went from 9% to 85.9%! And that was when it was just one TV you had to sit down to watch, and share the programming with your family. Children today will never understand the feral rage one can summon in a fight with your siblings to control the remote.

Fast forward to today when everyone is carrying a little TV in their pocket, our attention focused on TV has skyrocketed.

Meanwhile, the internet has surpassed TV time in terms of daily consumption worldwide.

Granted, at this point it all starts to blend together. We use the internet to do everything, whether its watching TV, consuming news, or reading. So its tough to segment the internet time. Instead, you can look at leisure activities and see that, while our time with television sets may have been passed by our internet time, its still watching TV that is taking up a big chunk of our leisure time.

So, as other mediums have pushed in to take our attention, that's had an overall impact on how books get made.

The Business of Books

Books are starting to blend together. In some cases, they literally look the same. Whether its the colorful abstract fiction novel...

Or the sterile white / off-white academic-ey non-fiction book.

Don't get me wrong, I've read several of these books and really liked them. But often these are the exceptions, not the rule. Some people have pointed to the increasing prevalence of pop psychology books. These books that come across as fairly scientific, but are often crafted to be the most attention grabbing. The clickbait or gossip magazines of the book world.

The business model behind books seem to be pushing what gets published to the least common denominator. For example, book lengths on average have come down to a pretty consistent ~250 page average.

Some people would say things like "well, authors used to get paid by the word, so we're just cutting out the fluff.” But that wasn't exactly true. I think it has more to do with our increasingly short attention spans.

As people read less and less, the book publishing industry is incentivized to get more and more dramatic and attention-grabbing. But the rub is that that has often been the case. Books like Moby Dick, The Sound and the Fury, Lord of the Flies, The Great Gatsby, The Waste Land, and Walden were all commercial disappointments that have gone on to be considered literary classics.

In our search for a higher quality medium, I think we can largely disregard the publishing industry and the marketing hype around any particular book. In the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson:

“Never read a book that is not a year old.”

Our pursuit of a better information medium isn't in a better publishing industry, but rather a reforming of our framework for the relationship between knowledge artifacts.

Building Back Books: Open Source Knowledge

I've written before about this idea of "open source knowledge":

"The world is a complex interconnected graph of all the things people know, and all the things people do as a result of what they know. Those ideas are constantly evolving, and any attempt to capture them is ridiculously difficult. Especially in internet time.

Content decays as ideas progress. Books don't change (and they're not great at conveying information in the first place). Bad information can stay online for years. One of the mistakes we make is believing that information is meant to be established and authoritative. Outside of a highly select set of "eternal truths," most ideas are meant to be fluid."

I've always credited Nadia Eghbal Asparouhova's book, Working in Public, for crafting this concept in my head. It's an exceptional overview of open source software and the affiliated communities. The idea of open source knowledge was so interesting to me, it became one of my portfolio ideas.

I also occasionally go to bat for the idea online.

As an abstract concept, comparing open access content to open source software can be really interesting. But what doest that mean in practice?

The Practice: Note-taking

Quick bio on me. Twitter was a COVID discovery for me. I never really used it until the lockdowns happened. And my first discovery on Twitter that changed my life? Roam Research. For the first year or so on Twitter, Roam was all I could talk about. Before I started writing on Substack consistently in 2022, the first piece I wrote was a massive encapsulation of how I use Roam in every aspect of my life, particularly in investing research.

A core fundamental truth that I gained from using Roam, and taking more notes, and using Twitter more often was this idea of the atomic unit of thought. Each idea is out in the universe as a singular atom. What is most important is your ability to connect that one atomic unit to other atomic units. The more connections you make, the stronger that corpus of knowledge. This is just like the neuroplasticity of your brain:

"The first few years of a child's life are a time of rapid brain growth. At birth, every neuron in the cerebral cortex has an estimated 2,500 synapses, or small gaps between neurons where nerve impulses are relayed. By the age of three, this number has grown to a whopping 15,000 synapses per neuron.

The average adult, however, only has about half that number of synapses. Why? Because as we gain new experiences, some connections are strengthened while others are eliminated. This process is known as synaptic pruning.

Neurons that are used frequently develop stronger connections. Those that are rarely or never used eventually die. By developing new connections and pruning away weak ones, the brain can adapt to the changing environment."

In Roam, I can keep track of quotes that resonate with me. Each of those quotes is one atomic thought. For example, this quote from F. Scott Fitzgerald: "The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function." If you've heard that quote before, its a loose connection in your brain. For me, I can see all nine references of where I've connected that quote before. For example, you can see I used it in my pieces on Post-Mortems, The Meme Economy, and what to build.

Now, to each their own on the system or process you use. But the key idea is creating the ability in every piece of information you ingest, from books to TikToks to Tweets / xeets to articles to podcasts, to identify (1) the atomic thoughts in that piece of content, and (2) the connections to other atomic thoughts you've come across. Andy discusses this exact practice in his overview on the weaknesses of books:

"Some people do absorb knowledge from books. Indeed, those are the people who really do think about what they’re reading. The process is often invisible. These readers’ inner monologues have sounds like: “This idea reminds me of…,” “This point conflicts with…,” “I don’t really understand how…,” etc. If they take some notes, they’re not simply transcribing the author’s words: they’re summarizing, synthesizing, analyzing.

Andy goes on to explain how this skill for connecting ideas and questions at at the atomic thought level has a name in learning science: metacognition.

The Science: Metacognition

Andy explains the relationship between metacognition and books this way:

"These skills fall into a bucket which learning science calls “metacognition.” The experimental evidence suggests that it’s challenging to learn these types of skills, and that many adults lack them. Worse, even if readers know how to do all these things, the process is quite taxing. Readers must juggle both the content of the book and also all these meta-questions. People particularly struggle to multitask like this when the content is unfamiliar.

Of course, great authors earnestly want readers to think carefully about their words. These authors form sophisticated pictures of their readers’ evolving conceptions. They anticipate confusions readers might have, then shape their prose to acknowledge and mitigate those issues. They make constant choices about depth and detail using these models. They suggest what background knowledge might be needed for certain passages and where to go to get it.

By shouldering some of readers’ self-monitoring and regulation, these authors’ efforts can indeed lighten the metacognitive burden. But metacognition is an inherently dynamic process, evolving continuously as readers’ own conceptions evolve. Books are static. Prose can frame or stimulate readers’ thoughts, but prose can’t behave or respond to those thoughts as they unfold in each reader’s head. The reader must plan and steer their own feedback loops."

Francis Miller, an awesome academic who I met through the RoamCult on Twitter, has a great piece that goes deeper into the cognitive load of metacognition entitled "Multi-level summaries: A new approach to non-fiction books."

In it, he contrasts the typical structure of a book as sequential vs. a subtextual meaning structure. The sequential structure looks like this:

Miller points out that every book has an implicit meaning structure (e.g. what they're trying to say.) But they don't typically weave the sequential structure to map to the meaning structure very well. Metacognition is the act of attempting to make the author's implicit meaning explicit.

Once you've articulated the meaning structure, it could look more like this:

Miller explains some of the negative implications behind the need for this translation from implicit to explicit meaning structures:

"Readers need to identify and understand the meaning structure if they are to get the most out of a book... The cognitive energy taken up by trying to make the implicit meaning structure explicit reduces the energy available for the more important tasks of understanding, assessment and reflection."

Another way to think about the explicit meaning of key ideas is going back to the idea of connecting ideas at the atomic unit level. Core ideas that relate to each other, but the complexity of the sequential structure make those connections harder to make.

David Perell has a great piece entitled "Hyper Publishing: The Wiki Strategy." He talks about hyperlinks as the foundation of the internet. One of the things the typical hyperlink is missing, though, are called "backlinks." Showing the back and forth relationship between an idea or piece of content. In Perell's piece, he has this sick image of the reference links in the Bible. "In the photo [below], every single line represents a Biblical verse. The length of each line is proportional to how many times that verse is referred to in some way by some other verse."

Those relationships represent powerful context to better understand those ideas. But you can't get access to that level of interconnectivity in the book itself. The way Perell explains it:

"While books store information, they can’t create idea trails. Books have too much friction."

Idea trails. So good.

If I could snap my fingers and shape the world of information creation and storage, I would make a universal knowledge graph. Everyone's notes, journals, books, texts, tweets, emails, thoughts, dreams, and everything in between would be stored on a giant graph. Every individual atomic thought would have a unique identifier (think an Excel reference, like A12).

Then, each time I referenced an idea from an email, or a memory from a journal, or a Tweet from someone, I could reference that atomic thoughts' reference. If its a private thought, only I can see the connection. If its a public thought, everyone can see it. So I could read a blog post, and I could see where anyone has ever referenced a particular paragraph in that blog post. I could filter by who used the reference; do I follow them? Do lots of other people reference them?

The great global knowledge graph.

But I can't. So, instead, Books 2.0 becomes more about the reader than the book.

Foundations of Books 2.0

"It's a poor craftsman that blames his tools."

For those who want to completely revolutionize the book as a medium, please do! #RequestForStartups

But for me, instead of trying to change the book medium, the best I can do is identify some of the core principles that I'm more focused on as opposed to how many books I read, or which books did I finish. Each of these could be their own piece, so I’m just sharing some snippets that inspire me on the topic.

Learning To Love Learning

You have to want new information as much as you want air.

"The ability to learn new things--whether thats calculus or hitting a fast ball--requires stretching your brain past the point of what's familiar or comfortable. And that stretch requires unbroken concentration." (Cal Newport)

“By learning, retaining, and building on the retained basics, we are creating a rich web of associated information. The more we know, the more information (hooks) we have to connect new information to, the easier we can form long-term memories. […] Learning becomes fun. We have entered a virtuous circle of learning, and it seems as if our long-term memory capacity and speed are actually growing. On the other hand, if we fail to retain what we have learned, for example, by not using effective strategies, it becomes increasingly difficult to learn information that builds on earlier learning. More and more knowledge gaps become apparent. Since we can’t really connect new information to gaps, learning becomes an uphill battle that exhausts us and takes the fun out of learning. It seems as if we have reached the capacity limit of our brain and memory. Welcome to a vicious circle. Certainly, you would much rather be in a virtuous learning circle, so to remember what you have learned, you need to build effective long-term memory structures.” (Helmut D. Sachs)

A Latticework of Knowledge

"Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience, both vicarious and direct, on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.” (Charlie Munger)

Identifying Cognitive Models

Andy refers to a need for understanding what he calls "cognitive models":

"If we collect enough of these underlying “truths,” some shared themes might emerge, suggesting a more coherent theory of how learning happens. We’ll call such theories cognitive models. Some learning strategies suggest the same model; others suggest conflicting models. Some of these models are empirically testable; others aren’t; still others are already known to be false. By focusing on these models, instead of a herd of one-off strategies, we can seek more general implications. We can ask: if we take a particular cognitive model seriously, what does it suggest will (or won’t) help us understand something?

To illustrate what I mean, I’ll try to draw on your own learning experiences. You’ve probably discovered that certain strategies help you absorb new ideas: solving interesting problems, writing chapter summaries, doing creative projects, etc. Whatever strategies you prefer, they’re not magic. There’s a reason they work (when they do): they’re leveraging some underlying truth about your cognition—about the way you think and learn. In many cases, the truth is not just about your cognition but about human cognition in general."

In other words, learning strategies. The most effective way to take a books 2.0 approach to learning is to understand how you learn. How you think.

There are other disciplines for further study that are in various levels of proven vs. debunked, but I think still informative. One of my favorites is the theory of multiple intelligences from Howard Gardner

Exposure To Opposition

Another key benefit of developing a fine-tuned "books 2.0" approach to learning is the exposure to opposition when it comes to your ideas:

"I have what I call an "iron prescription" that helps me keep sane when I drift toward preferring one intense ideology over another. I feel that I'm not entitled to have an opinion unless I can state the arguments against my position better than the people who are in opposition. I think that I am qualified to speak only when I've reached that state. (Charlie Munger)

In fact, this is one of the critical failings that people are worried about when it comes to people's decreasing book consumption. In The New Yorker, Caleb Crain makes this point:

"Emotional responsiveness to streaming media harks back to the world of primary orality, and, as in Plato’s day, the solidarity amounts almost to a mutual possession. “Electronic technology fosters and encourages unification and involvement,” in McLuhan’s words. The viewer feels at home with his show, or else he changes the channel. The closeness makes it hard to negotiate differences of opinion. It can be amusing to read a magazine whose principles you despise, but it is almost unbearable to watch such a television show. And so, in a culture of secondary orality, we may be less likely to spend time with ideas we disagree with."

So, the less we're reading, the less comfortable we are with confronting ideas that oppose our own. And that makes us less well-equipped, in the words of Charlie Munger, to be entitled to have an opinion."

Dreaming The Dream

Science Fiction as a Road Map

Andy makes a key point about the world of information transference today that is, interestingly, addressed in a bunch of science fiction:

"Lectures, as a medium, have no carefully-considered cognitive model at their foundation. Yet if we were aliens observing typical lectures from afar, we might notice the implicit model they appear to share: “the lecturer says words describing an idea; the class hears the words and maybe scribbles in a notebook; then the class understands the idea.” In learning sciences, we call this model “transmissionism.” It’s the notion that knowledge can be directly transmitted from teacher to student, like transcribing text from one page onto another. If only! The idea is so thoroughly discredited that “transmissionism” is only used pejoratively, in reference to naive historical teaching practices. Or as an ad-hominem in juicy academic spats."

There's so much more I could dig into about how the future portrays information sharing. But this idea of "transmissionism" immediately reminded me of the Matrix where Neo "uploads" Kung Fu.

Here are some other sci-fi examples that ChatGPT gave me (I didn't fact check them, so hallucinate to your hearts desire):

Movies:

"The Matrix" (1999) - This iconic film directed by the Wachowskis introduces the concept of a simulated reality where characters can download various skills and abilities directly into their minds.

"Johnny Mnemonic" (1995) - Based on a short story by William Gibson, this film features a data courier with a neural implant that allows him to store and transport sensitive information in his brain.

"Inception" (2010) - While not about downloading skills, this Christopher Nolan film delves into the manipulation of dreams and the mind, showcasing technology that can access and influence a person's subconscious.

"Transcendence" (2014) - In this film, a scientist uploads his consciousness into a supercomputer, exploring themes of artificial intelligence and the merging of human and machine.

"Lucy" (2014) - Though more about unlocking human potential through brain-enhancing drugs, this movie features a protagonist who gains superhuman abilities as her brain's capabilities expand.

Books:

"Neuromancer" by William Gibson (1984) - This novel is a seminal work in the cyberpunk genre and features characters with neural implants and interfaces, as well as hacking into cyberspace.

"Snow Crash" by Neal Stephenson (1992) - In this cyberpunk classic, characters use a drug called Snow Crash and a virtual reality metaverse for hacking and manipulating neural interfaces.

"Altered Carbon" by Richard K. Morgan (2002) - The novel explores a future where people can transfer their consciousness between bodies, effectively achieving immortality through cortical stacks implanted in their spines.

"Daemon" by Daniel Suarez (2006) - The book features an AI-driven system that influences people's actions through neural implants, raising questions about the intersection of technology and control.

"Nexus" by Ramez Naam (2012) - Set in a near-future world, this novel explores the development of a mind-enhancing nanodrug called Nexus, which can link human minds and abilities through neural interfaces.

There's so much more here in thinking about science fiction as a road map, but in the heat of my panic writing I'm limited. On top of that, there are other really cool projects, like Books in Progress that I could explore. But I've been panic writing for 4.5 hours and it's about time to hit send.

Therefore, What?

Learning is a personal responsibility. Educational systems, parents, governments, mentors. Everyone can create incentives and encouragement and programs. But ultimately we are very much a horse that will only drink water of our own accord, regardless of who led us there.

Questioning the quality of a book's ability to transfer information has made me more thoughtful about the explicit subtextual meaning behind the content that I'm reading. And as a result, although I read fewer books, I'm more focused on expanding the myriad of connections in the synapses of my conceptual knowledge graph.

And you should too.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

What an amazing write up. I feel that most industries not just VC or edication have a huge issue with actually thinking about how to help and guide the new students of their industry.

I didn't really see this until I started working on my own startup to help founders using AI. A big issues which ties into your chain of idea thought is that as a founder/vc/or other person who needs to learn things, you try and craft your own strategic chain of ideas or lessons that you need to then find the resources for.

The issues as you mentioned is that the resources are all based on books 1.0, so there is an inherent ineffectiveness that is built in. That people who are veterans overlook and blame the people for (ad-hominem). Meaning most industries are never able to actually bring in disruption or innovation to the education infrastructure that they are built on.

2nd point is that books and most other mediums don't give the studen the ability to see all of their options. Meaning they only see what is presented, or more commonly said "they don't know what they don't know". This what is commonly referred to as tribal knowledge or the "when you've done your time" type of knowledge.

There is a solution though. As there is a clear line of how AI is going to bring about a new form of leanring, that is way more efficient. It's this belief and exploration of this new UI/UX over the existing data that we are riding on. Where you show a founder all options given a topic, and then personalize the explanation on their needs. This reduces a ton of the friction from books 1.0, while allowing for deeper learning through conversation, and the ability to immediately act on the new knowledge. It's been proven that the act of doing or teaching back dramatically improves retention and understanding. AI removes the friction from doing, and can be there every step of the way to provide course corrections when the user needs it.

To me Book 2.0 isn't a new medium, but a new ui/ux for the existing and new educational data.

Great piece!

I agree with you insofar as your assertion that “reading” is just the first step. There has to be a distillation, a reflection of what one has read in order for knowledge to be transferred from medium to individual

But I don’t think this supports your assertion that books are ineffective at doing so.

The fact that most books are not “quake books” or that many modern nonfiction books could have been a blog post or that most people don’t derive value from reading, sounds like a skill issue, on authors and consumers respectively

Nevertheless I may be biased due to my own love and admiration of excellent writing and I appreciated reading your take