This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

COVID created a real time warp. It might shock you to hear that in a few months, it will have been four years since lockdowns started in the US. There is someone out there who was just starting high school when we went remote, and now they're gearing up to graduate.

So that same time warp may make it feel funky that I'm spending a lot of my time this week thinking about and responding to a four year old essay. But in the (paraphrased) words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, "never read a book that's less than a year old." In the early days of COVID, Marc Andreessen put out an essay called "It's Time To Build." In it, he criticized the seriously lacking building capabilities "throughout Western life, and specifically throughout American life."

Since releasing that essay, Andreessen also published The Techno-Optimist Manifesto. This, among several other thought pieces, has crystalized a growing dichotomy between effective altruism (aka EA) and effective accelerationism (aka e/acc). As I've been thinking about the sudden dominance of e/acc, the world view it offers, and the things that are most important, I think many of the ideas behind accelerationism can trace some roots to Marc's "Time To Build" piece.

What's more, reflecting on these ideologies has left me attempting to unpack them to first principles. I believe in progress, and accelerationism in its rawest form. But my bigger question becomes, "...build what?" Because all building is not created equal. All progress is not in our best interest. Accelerating at all costs can be just as easily directed at a brick wall as it is at a utopian future. So I wanted to stop as we approach the close of the calendar, and reflect on that question that's been nagging at me all year.

Barely Building

Marc's criticism is a fair one. We've grown increasingly incompetent at building in the physical world. The US went from producing 3K aircrafts in 1939 to a few years later producing 96K aircrafts per year. Over the course of the war effort, the US would produce 88K tanks, 2.4M trucks 41B rounds of ammunition, and 2.7K ships. In fact, the production process was so efficient that some ships were built in less than a month, with one being completed in just over four days.

In the late 1800s / early 1900s, we used to have World Fairs that would consist of massive undertakings. The 1964-1965 New York World's Fair spanned 650 acres, and 140 pavilions representing 80 different nations. The 1889 Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris had the Eiffel Tower originally built as the entrance arch! Think about how many weddings you've been to with balloon arches. Now imagine a party where the balloon arch becomes the defining characteristic of the city where the wedding took place for 100+ years. Solid arch work.

The 1962 World's Fair in Seattle was the same, leading to the creation of the Space Needle! The Eiffel Tower and the Space Needle took just 2 years and 1 year respectively to build. Name the last time we did something like that. Now, granted, we have some people trying to bring back the World's Fair, but that culture has really disappeared.

What's taken its place? Mass production, quality destruction, and eventually production failure. Starting with Ford's assembly line for the Model T, we started to focus on quantity over quality. Offshoring further prioritized efficiency of cost, rather than efficiency of quality. What's more, we saw the introduction of planned obsolescence.

Planned Obsolescence

A critical antithesis of building things that last for a LONG time is the profit-driven motive to build replacement into specific products. One example sparked a conversation online a few months ago that stood out to me. Ben Schwartz's recreation of a Billy Crystal look from the 80s drew attention to the quality of sweaters over time. Our grandparents used to make clothes by hand. We traded craftsmanship for convenience, and in the process gave up a capability.

There are tons of examples of this across dozens of different markets:

Lightbulbs

Potentially one of the most famous, and chronicled, attempts to force products into replacement is lightbulbs. In the 1920s, the Phoebus cartel came together for the nerdiest shakedown in history—they were going to make lightbulbs die quicker. Companies like GE, Osram, and Philips got together in Switzerland and agreed to standardize the life of a lightbulb at 1,000 hours.

Previous bulbs had demonstrated the ability to last for more than 2,500 hours. But the profit motive indicated that a lightbulb that lasted half as long allows you to sell twice as many lightbulbs.

The Centennial Light stands as a stark condemnation of the average lightbulb infested with Phoebus-induced limitations. A lightbulb that was turned on in 1901 is still burning in Livermore, California. There's a 24/7 web-cam where you can check in on the glorious demonstration of human achievement.

Computers

Look no further than the myriad of different ports Apple has foisted on us over the years. Every computer has built in plans to force you to look for replacements, whether its for the software, hardware, battery, etc.

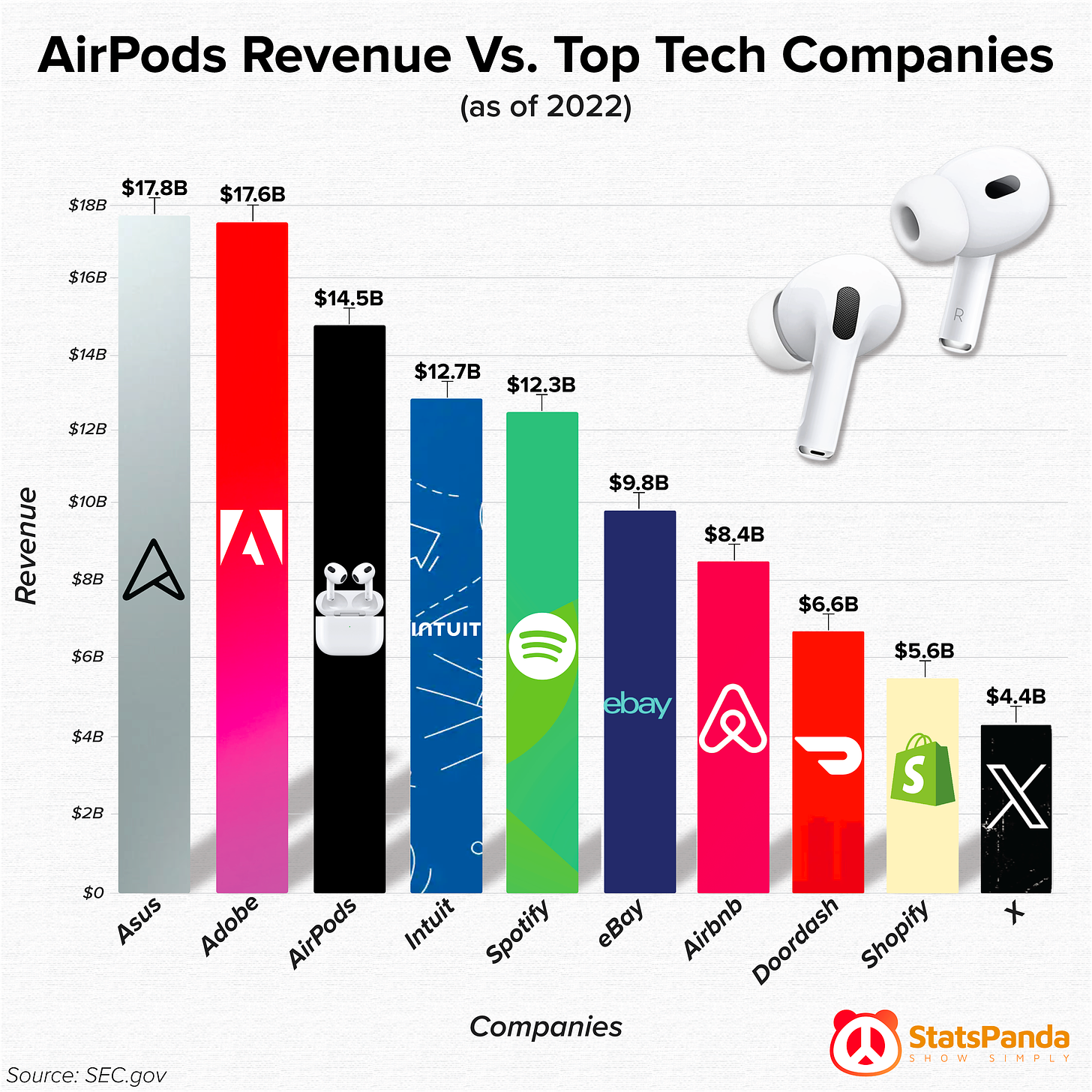

Think about Airpods. Their batteries are built to need to be replaced. One of the reasons that Airpods has become such a massive revenue driver in its own right isn't just because of popularity. Having to replace our Airpods has effectively become a recurring revenue line item for Apple.

Build How?

Whether it's a result of excess capitalism, laziness, emphasis on convenience over quality—whatever it is, it just seems like we're getting worse at building pretty much everything. No doubt, there are clear exceptions. SpaceX's rockets have fundamentally changed the cost equation for getting things into space in a way that most people thought was impossible. But we're surround by examples of our inadequacies as a building species.

The Las Vegas Grand Prix was scheduled to take place in early November this year, but the race quickly turned into a disaster. Drivers were damaging their cars due to improperly secured drain covers. Spectators were turned away due to security risks and scheduling issues.

You might feel like you're hearing a lot more about different products getting recalled. You're not wrong. The total units of food recalled in 2022 was 700% higher than 2021, with cases like Tyson recalling 30K pounds of Dino-Nuggies because of pieces of metal being found in them. Don't even get me started on baby formula. The same is true of cars. Cases like 2M Tesla's being recalled for issues with autopilot. Or Ford recalling 4M vehicles in 2023 alone.

Infamous projects, like Boston's "Big Dig" represent Herculean dramas of failure. The Wikipedia entry left me gobsmacked:

"The Big Dig was the most expensive highway project in the United States, and was plagued by cost overruns, delays, leaks, design flaws, charges of poor execution and use of substandard materials, criminal charges and arrests, and the death of one motorist. The project was originally scheduled to be completed in 1998 at an estimated cost of $2.8 billion (in 1982 dollars, US$7.4 billion adjusted for inflation as of 2020). However, the project was completed in December 2007 at a cost of over $8.08 billion (in 1982 dollars, $21.5 billion adjusted for inflation, meaning a cost overrun of about 190%) as of 2020. The Boston Globe estimated that the project will ultimately cost $22 billion, including interest, and that it would not be paid off until 2038."

Practiced Pondering

I've written before about "the Axis of Building." In that piece, I quoted Noah Smith talking about our position as a "build-nothing country":

"Slashing the thicket of red tape that prevent development, and subordinating local interests to the needs of the nation itself, are no longer idle dreams — they are immediate necessities. If we insist on continuing to be the Build-Nothing Country, our once-mighty middle class will sink into a genteel poverty, and someone else will build the future on the bones of our civilization."

He touches on a critical idea. The idea that building often amounts to little more than "idle dreams." Andreessen touches on a similar idea in his "Time to Build" essay:

"Part of the problem is clearly foresight, a failure of imagination. But the other part of the problem is what we didn’t DO in advance, and what we’re failing to do now. And that is a failure of action, and specifically our widespread inability to BUILD.

The problem is desire. We need to WANT these things. The problem is inertia. We need to want these things more than we want to prevent these things. The problem is regulatory capture. We need to want new companies to build these things, even if incumbents don’t like it, even if only to force the incumbents to build these things. And the problem is will. We need to build these things."

There is a clear relationship between having a dream. A successful imagination. And then leveraging will-power in pursuit of that dream. But here's the rub. We start to get into nuanced territory where beliefs and actions don't always easily align. Marc Andreessen offers a very specific demonstration of this conundrum in some of his own activities and investments.

Marc's Capitalist Conundrum

Here's the timeline. In early 2020, Marc wrote the "Time to Build" essay. In it, one of the things he decried was our failure to build housing:

"You see it in housing and the physical footprint of our cities. We can’t build nearly enough housing in our cities with surging economic potential—which results in crazily skyrocketing housing prices in places like San Francisco, making it nearly impossible for regular people to move in and take the jobs of the future."

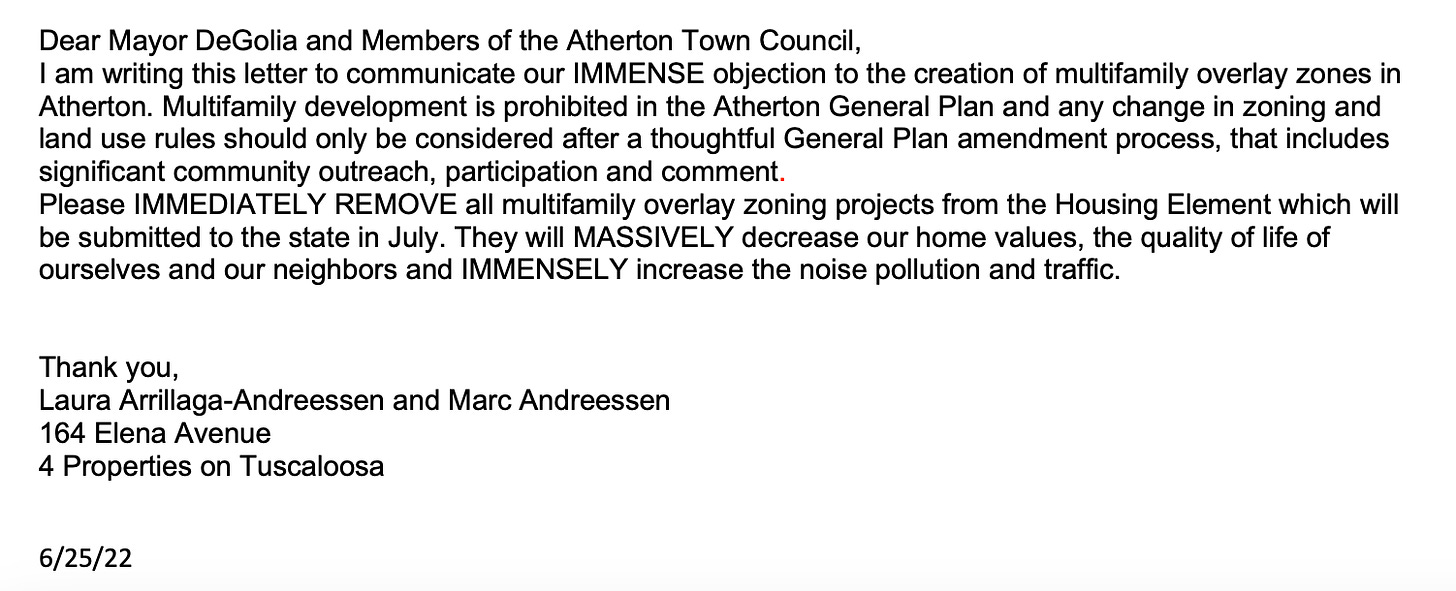

Fast forward to August 4th, 2022. Marc Andreessen's hometown in Atherton, California (the most expensive zip code in the US) had some proposed plans to build multi-family homes. Andreessen and his wife wrote in a public comment (which now seems to be taken down) that they were very much against the planned multi-family housing. A response commonly referred to as NIMBYism ("Not In My Back Yard"…ism).

The sequence of events can't help but strike you as funny. It reminds me of this Neal Brennan bit. But the plot thickens.

One more fast forward. Just a few weeks later on August 15th, 2022 a16z announced they were writing their largest single check into Adam Neumann's new company, Flow. Neumann's pitch played seemingly right into the same "housing shortage." In a16z's announcement, Marc Andreessen expressed a similar sentiment to his "Time To Build" essay:

"The demographic trends driving America’s housing market are impossible to ignore: our country is creating households faster than we’re building houses. Structural shortages in available homes for sale push housing prices higher, while young people are staying single for longer and increasingly concentrating in highly desirable urban centers. These factors put enormous pressure on rents in the nation’s most dynamic cities, starkly revealing the troubling realities of both sides of the housing market’s two historical models."

So. After driving WeWork up to $47B and down into eventual bankruptcy, what was Adam Neumann building? I wrote about the announcement at the time in a piece titled "The Rise of The Cash Man." In it, I quoted another piece that was pretty brutally honest about what Neumann seemed to be building:

"While offering people the ability to gain some sort of equity stake in their apartments could help people build wealth, Flow’s rentals are probably for those who are already relatively rich. The Nashville property Neumann bought, for instance, features a saltwater pool, valet trash pickup, and a dog park."

Some Caveats & Pre-Conceived Conclusions

I've written before about this relationship between beliefs and actions. Changing it slightly, but your actions ought to be lagging indicators of your beliefs. In religion, you often have what people refer to as "Sunday school answers." How do you be a good Christian? "Read your scriptures. Say your prayers. Go to church." But often, these Sunday school answers are true. And they strike of first principles.

Here's another Sunday school answer / first principles truthism: "Actions speak louder than words."

And here's the other thing. I don't mean to crap on Marc Andreessen. I have intense respect for him and what he's built with a16z. My whole vibe is attempting to live within the grey areas of nuance. Going back to what I've written before about beliefs, and actions. I think its important to attempt to define your own beliefs, not just use your in-group as a proxy:

"So often, people trust nuanced tribal group identity and political association without any basis of first principles. I'm not Mormon, or Christian, or Republican, or a Costco member. I am a system of values and beliefs that determine how I act. Group membership should be a lagging indicator of your beliefs, not a leading indicator. When people substitute their own value system with a cookie-cutter platform from their in-group the first thing to die is nuance."

So despite my in-group default to assume other VCs are doing what's best for technological progress, I instead choose to acknowledge nuance. I can simultaneously believe that Marc Andreessen is an exceptional investor and company builder, while also being inconsistent in (1) believing we need to build more housing, (2) deploying a NIMBY strategy in his hometown, and (3) funding a company that is likely going to do more for rich people than it will in solving the housing crisis.

Another great quote to illustrate the importance of embracing nuance is a favorite of mine from F. Scott Fitzgerald:

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function."

All of this context informs how I'm reflecting on this most recent culture clash between accelerationism and “decelerationism”. On the one hand it is build or die; on the other, it is slow and steady. But I refuse to live in black or white. I strive for the acknowledgement of nuance in everything I do. So lets apply the lens of nuance to the question of growth.

Growth, At What Cost?

At its core, capitalism is built on the principle of continuous growth. Ideas like profit motives, competition, and maximizing shareholder wealth are all driven by identifying opportunities to drive growth. VCisms like "growth at all costs" and "move fast and break things," are trickle-down reflections of core pillars of capitalism. You want to drive growth.

Herein lies the nuance. Growth is not always a good thing. Every tech company is learning that in real-time. Am I decrying every form of economic growth? No. Am I calling for a Marxist revolution to level out any growth? No. The nuance is in saying that growth, when it comes from buying $1 in exchange for $2, is bad growth.

Think about the story of the scorpion trying to get across the river. Funny enough, the last time I wrote about this story was also a piece I wrote about Adam Neumann:

"A frog is hanging out by a river. A scorpion comes along, and asks the frog to carry it across. But the frog is no dummy. "Listen," says the frog, "I've been around scorpions before. Y'all have a tendency to sting things." The scorpion chuckles, "Now, why would I do that? If I did that, I would drown too!" The frog is convinced by the logic, and proceeds to let the scorpion saddle up.

Half way across? The scorpion stings the frog after all. "Why would you do that?" the dying frog asks. "The scorpion looks perplexed, as it sinks into the water. "Sorry. I couldn't help it. It's in my nature."

A lot of people who have built business models and marketing machines around growth could be accused of living by the same sentiment. Why grow? "It's in my nature." Another way to say the quiet part out loud would be to say these $2 for $1 growers are declaring, "it's in my nature, even if it's to my detriment."

Growth has a tendency to deprioritize most other things. Take one example. Since being founded in 1978, Ben & Jerry's has always emphasized their focus on sustainability. The company has grown to $2B+ in revenue. But that growth has brought with it an inability to reasonably maintain sustainably sourced ingredients, manageable environmental impact, or consistent use of fair labor, and animal welfare.

Is that bad? $2B is nothing to sniff at. It's all a function of what you are solving for. Most people would say if you're not growing, you're dying. But, once again, we're all living through a wakeup call shaped like an economic efficiency punch to the face. So embracing the nuance of balanced growth isn't a bad thing.

A Global Down Round

I keep feeling the obligation to reinforce this. I believe in progress. I'm a fan of the focus on accelerationism. I don't want to see progress locked away behind corporate monopolies or government negative Nancy's (nancies? Nancy-ites?). But in some respects, the global economy may need a down round.

For years, companies were rewarded for "growth at all costs." That's how you got markups. That's how you won customers. That's how you made great hires. Capitalism is very similar; it existentially drives towards growth above anything else. When people talk about the social injustices of capitalism, they often focus on the idea of externalities. Economic growth isn't forced to bear the brunt of unjust labor or environmental impacts or health issues. The same way companies aren't forced to bear the burden of unsound unit economics, unsustainable growth, or burnout cultures. Or at least, they weren't until recently.

The analogy can continue. I'm not talking about eradicating, politicizing, or outlawing growth anymore than I want startups to stop caring about growth entirely. But the conversation in company building over the last two years has centered around profitable growth. That doesn’t mean no growth. And that certainly doesn’t mean deceleration. It doesn’t mean closing up shop and just planting flowers and writing poetry

Profitable growth is growth with a purpose. Purposeful growth.

The Power of Purposeful Progress

"Growth at all costs."

"Move fast and break things."

"Blitzscaling."

The sudden emergence of effective accelerationism (e/acc) is the newest framework for the grow-or-die mantra. There isn't much of a mechanism in e/acc for purposeful growth. And, in fact, calling for any form of limitations on e/acc will be given the scarlet letter; branded as a decel.

The conversation is fertile ground. Marc Andreessen's "Techo-Optimist Manifesto." Noah Smith's "Thoughts on techno-optimism." Vitalik Buterin's thread on techno-optimism and the fear of decentralization, whose piece points to other responses in its own right, Robin Hanson, Joshua Gans, Dave Karpf, Luca Ropek, Ezra Klein, James Pethokoukis's "The Conservative Futurist" and Palladium's "It's Time To Build for Good". The Information's declaration that the e/acc movement is "a cult." Explanations from Beff Jezos. Threads on "science fact vs. science fiction" from Josh Wolfe. Molly White's piece on "effective obfuscation."

Andreessen, once again, puts into words the "growth before life" mentality:

"Techno-Optimists believe that societies, like sharks, grow or die. We believe growth is progress – leading to vitality, expansion of life, increasing knowledge, higher well being. We agree with Paul Collier when he says, “Economic growth is not a cure-all, but lack of growth is a kill-all.” We believe everything good is downstream of growth. We believe not growing is stagnation, which leads to zero-sum thinking, internal fighting, degradation, collapse, and ultimately death."

He goes on to list a laundry list of "enemies" to this optimism. Some of them, like "deceleration, de-growth, depopulation," I agree with fighting against. I want progress, advancement, and human expansion. But where I see the nuance is when he points to governments and bureaucracies as enemies. Not everyone you disagree with need be an enemy. That nuance is well-articulated by Noah Smith's response piece:

"Because sustaining technological progress is so hard, it needs a whole-of-society approach in order to get it right. It’s not something that can be adequately handled only by big corporations, or only by VC-funded startups, or only by universities, or only by the government, etc. etc. These different innovators all focus on different areas of technology and have different incentive structures, so we need them all."

Smith goes on to really masterfully articulate the nuanced balance that I've been trying to strike in my own perspective on techno-optimism.

Normativity of Human Nature

I could quote six or seven paragraphs from Noah's piece, but instead I'll try and build a Frankenstein quote that adequately reflects the bits that resonated with me about normative techno-optimism, and the role that human nature plays in progress:

"Normative techno-optimism says that more technology will make the world a better place for humanity. In fact, this kind of techno-optimism is surprisingly rare — even some of my favorite science fiction stories are implicitly or explicitly built around the idea that no matter how our capabilities improve, humans’ fundamental brutish nature will never change.

[But] I’m more of an active than a passive optimist. Whether it comes to sustaining the rate of innovation or making sure that innovations benefit humankind, I think that choosing the right policies is very important.

The very same externality that assures me that there’s lots left to discover is also the reason why we might not discover it. In particular, there are two things I’m worried about here. First, I worry that political chaos and division in rich countries (especially the U.S.) will make us less willing to fund R&D — already there are worrying signs, such as Congress stalling the science funding of the bipartisan CHIPS Act. And second, I worry that China’s theft of intellectual property has reached such enormous proportions that other countries’ return to innovation has fallen.

The main reason I think technological progress is usually good for humanity — why I’m a techno-optimist of the “normative” variety — is that I fundamentally believe that humans should be given as much choice as possible. This isn’t something I can prove with facts — it’s just a moral intuition. I am a humanist. I see human beings wanting things, and I want to give them what they want. This doesn’t always mean humans will be happier when they get what they want; sometimes we make choices that make us unhappy. But as a humanist, I believe my species has the right to choose."

Hopefully Noah Smith can forgive me for butchering his exceptional writing together to attempt to articulate my own point. But there is fundamental line that runs through this thinking. He encapsulates it perfectly when he says, "Innovation requires faith in society, while it’s lack of faith ultimately leads to decelerationist impulses."

My idea of purposeful growth is one that attempts to account for an "all hands on deck" approach to solving problems, rather than a "get out of my way" mentality. As much as I philosophically agree with the ideas that Marc and e/acc proponents articulate, there is a nagging in the back of my mind. Marc's essay espouses this idea of "intellectual natural selection":

"The techno-capital machine makes natural selection work for us in the realm of ideas. The best and most productive ideas win, and are combined and generate even better ideas. Those ideas materialize in the real world as technologically enabled goods and services that never would have emerged de novo."

And again, thats a fundamental view that I want to believe in. I also want an infinite upward spiral of intelligence and energy. I want every person on earth to feel like every physical good is as accessible as a pencil. I want people to be able to have (and support) more children than ever. Being a parent is everything to me, and I want everyone to have the ability to feel secure in growing the human population without fear of distress or resource fatigue.

But the reality is things are breaking. We're not just raging on in an ideal growth euphoria. The best ideas are demonstrably NOT winning. Look no further than government for the failings of ideological meritocracy. Whether a policy has 0% public support, or 100% public support, there is still a 30% chance that Congress will pass a law that supports it. The quality of an idea has a statistically insignificant influence on whether its enforced by law.

The same forces that stopped nuclear fission will try to stop nuclear fusion. The same forces that promoted starvation wages will promote AI-replacement over AI-augmentation. The reason we don't build is not because we don't want abundance. It's because sacrificing other people's abundance has become the cost line in the profit motive of larger organizations or larger-than-life people.

And what's more, people continue to defer their thinking to in-groups whose philosophies they seem to agree with. But that same tribal proxy thinking is making people nervous.

The Decels of E/acc

As powerful as accelerationist ideas can be, there is a growing concern about e/acc as an ideology. In a piece from The Information a few months ago, several people expressed their concerns with the e/acc movement:

"Christian Keil, chief of staff at satellite startup Astranis, initially put e/acc in his Twitter bio as a public proclamation that he was a “tech optimist.” But the movement’s endless memes and decel shaming don’t appeal to him. “There’s an element of this whole thing that’s very 4chan-y,” he said. “So I try to stay away from [it] as much as possible.”

“There was very little talk about what the future is,” [Rahul Rai] said. Instead, he said, they were just calling out decels. “They have this immediate thing of if you’re not e/acc, you’re a decel,” Rai said. “It’s very much how cults and religions operate, because that builds cohesion and unity amongst the people that are within the e/acc community.” He doubled down on that statement: “It’s a cult.”

Molly White articulated a pretty direct criticism of the concern that people have over this expressed unwieldy optimism that a lot of people are focused on:

"Despite their differences on AI, effective altruism and effective accelerationism share much in common (in addition to the similar names). Just like effective altruism, effective accelerationism can be used to justify nearly any course of action an adherent wants to take."

The fear with e/acc as a movement is not in the fundamental ideas of progress and optimism and effort. Its the unabashed cultural absolutism that, once again, is choking out nuance. You may be getting on the bus, shaking your fist in air, crying out the ra-ra cry of progress! And then progress directly into a brick wall of negative externalities and disappointments. Along the way, anyone attempting to point out the "brickyness" of the oncoming wall was tossed out the back of bus through a door marked "decels beware."

If we're going to build, that doesn't feel like a foundation upon which you want to build.

So... Build What?

I've written a number of pieces that are breathy exasperations of my internal monologue. Pieces like "Where Have All The Good Ones Gone?" and "The Renaissance of Rise and Grind." Often at the end of a piece like this one, I'm confronted with a pretty powerful question from Boyd K. Packer. "Therefore, what?"

I have continued to caveat throughout my thinking here. I do want to build. I want to support companies that are building. I want to build things that solve real problems. I want to build things that improve people's lives.

But, above all, my hope is that everything I do can have a sense of genuineness. I look at the hucksters that plague the company building world, and I can see their profit motives dripping through their teeth. I can hear the calls for altruistic acceptance disguising accusations of 1984 "thought crimes." Everything is so riddled with two-facedness.

I'm not crying for deceleration. I'm not crying for an aversion to growth or progress. But I'm hoping for a healthy dose of self-reflection in being willing to identify where there are issues with your own ideology. And where there are issues, lets attempt to find better alternatives together. Lets avoid the tribalistic blame-game, and instead identify synergistic paths for mutual benefit.

Don't take e/acc out of your Twitter bio. But don't define yourself by your ability to out a decel before anyone else, either. Define yourself by what you contribute, not what you contest. And have the willingness to be your own judge, jury, and executioner on whether your contributions are adequate or not.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

It's funny to me that tech VCs are talking about "acceleration". Isn't it well-understood in our industry that picking the right problems to solve is even more important than executing with velocity on those problems? Instead of effective accelerationism, why aren't we talking about effective problem-identification-ism?

Regarding "wanting to give humans what they want", I'd observe the word "want" conflates urges with intentions. Giving humans what they *intend for* is fraught enough (paving the road to hell and all that); but often that's not even what we're doing in tech. Instead we're optimizing for clicks, for satisfying humans' immediate impulses. Is this really what we want to accelerate?

Sure, maybe that's the "effective" part of "effective accelerationism", but I think the "accelerate" part is 1000x easier than the "effective" part and if we are promoting any kind of accelerationism we're much more likely to accelerate *something* that will probably be the wrong thing.

Very interesting piece, thank you. Indeed true that a lot of the goods and services we consume today are becoming tech-enabled / based. I recently wrote about how every company is becoming / converging to a X-as-a-Services model (x being a good / service).

Is Every Company Becoming a Software Business?

https://brandanatomy101.substack.com/p/is-every-company-becoming-a-software