This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In an episode of Silicon Valley, Pied Piper has grown to a sizable company and now has an HR department run by a woman named Tracey. Gilfoyle, the self-proclaimed satanist anarcho-capitalist is falling behind in his programming backlog. In response, Gilfoyle says "I'm more concerned with being right than being fast." Tracey pushes him to bring on more people to help with him with his workload.

In an act of rebellion, Gilfoyle brings on the barista, the security guard, and the plant waterer to be his "team." When Tracey confronts him about the team, he informs her that his new team all need to update their Linkedin statuses to "placaters of middle management."

Tracey criticizes Gilfoyle's decision to get into a "dick measuring contest," rather than accepting his limitations. Feeling threatened, Gilfoyle asks to see Tracey at the end of the day. He informs her that he's finished his entire backlog in 24 hours. Tracey's response?

"You said I had to choose. You said I could have it fast, or I could have it right. But I just got it fast and right. And all I had to do was threaten your manhood by assigning you other coders."

Gilfoyle's response?

"I respect your skills."

You Get What You Pay For

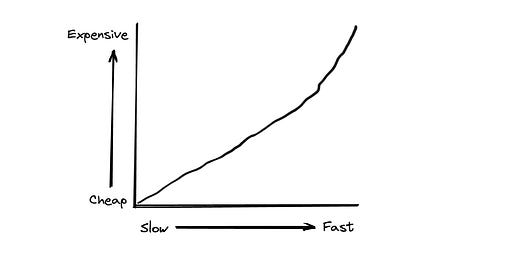

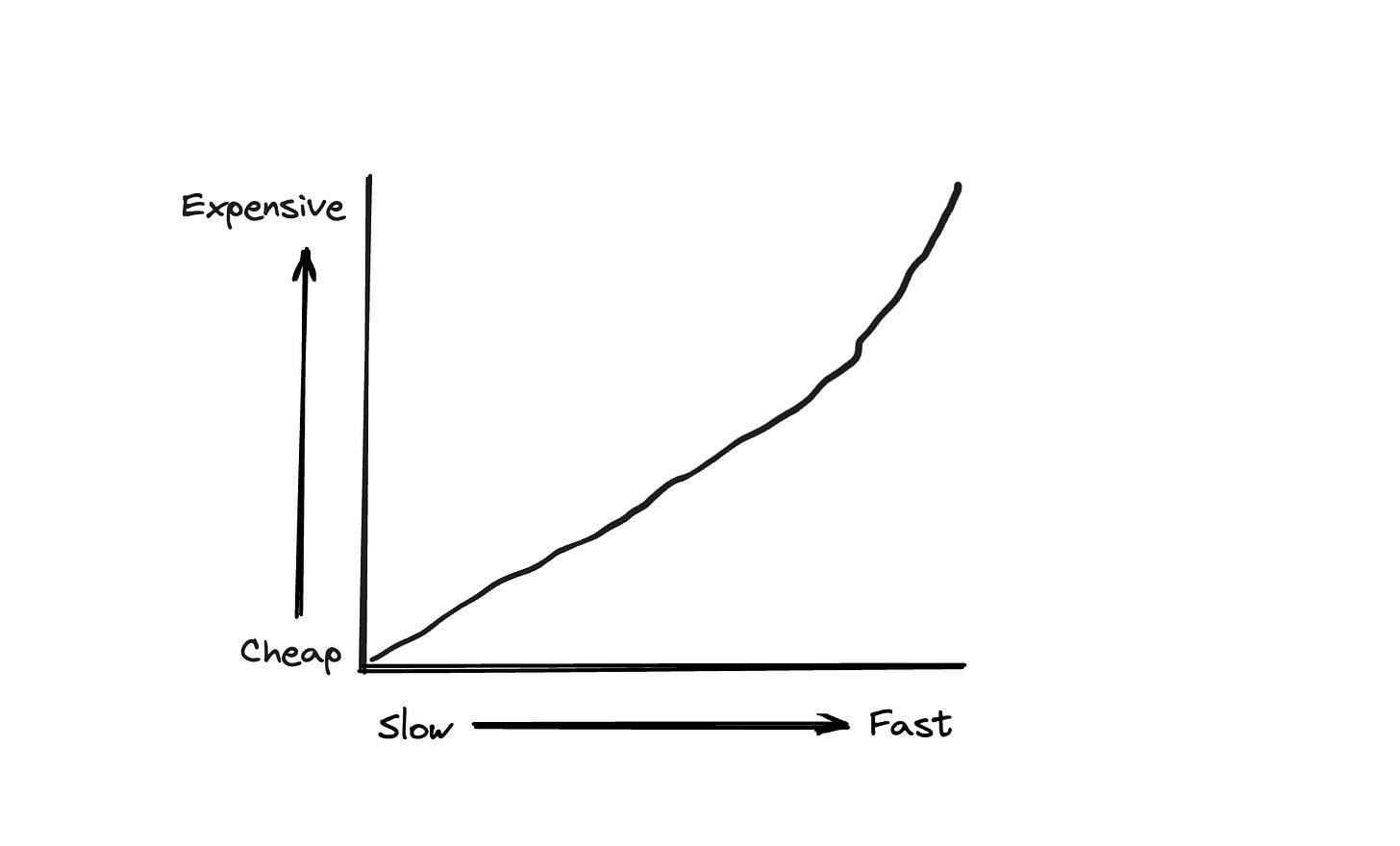

In an individual exercise, like coding, the trade off is usually what Gilfoyle described: fast vs. right. But in multi-person projects, like creating companies, or building infrastructure, or launching rockets, the trade off is more typically a function of speed vs. cost.

As the world starts to reset and focus so much on profitability, it's easy to lose sight of what people are actually trying to measure. The bigger picture revolves around efficiency. Getting to $1B in revenue is super impressive. But it's dramatically less impressive if it takes you $20B to get there. It stops being impressive at all, and just becomes ridiculous if it will consistently cost you $20B to generate every $1B of revenue no matter what.

People talk all the time about "economies of scale," the idea that the cost of something decreases, either because you do it more often, or because more people are using it. As one example, look at the cost to get someone into space.

The first official manned space flight was the Russian mission Vostok 1. In the US, Project Mercury was the first mission to take humans into space. The project ran from 1958 to 1963, involved 2M people, and cost $2.2B in today's dollars.

In November 2020, SpaceX launched Crew-1, their first manned mission. That flight took 4 people into space at an estimated cost of $254M ($63.5M per person). Just ~11% of the cost of Project Mercury. We learned how to do something, and then increasingly we learned how to do it much cheaper.

But, unfortunately, that most certainly isn't always the case.

Case Studies of Cost

While the cost of getting someone into space is a great example of improving costs, the reality is that the US gave up on getting people into space in 2011. It required SpaceX, a private company, to jumpstart that muscle again so that they could dramatically reduce the cost. Most often, the easiest place to find places to criticize costs will come in government. In particular, infrastructure projects.

It costs New York $2.6B per mile of railways or subways that they want to build. (For comparison, its costs $65M per mile in Spain).

The MTA spending $100M to build platform barriers at 3 subway stations in New York

New York worked to replace eight escalators and upgrade some fire alarms, and it cost $62M (which is ~13% of what it cost to build the Hoover Dam).

San Francisco spending $1.7M to built a single toilet, and it's going to take 3 years!

Seattle is planning a project to build bike and bus lanes, and it's going to take them longer to complete than it took the US to put a person on the moon.

In general, it takes the US government 3.5 years to review any individual renewable energy project.

La Sombrita was a project that built ineffectual shade structures at bus stops, all to avoid triggering "multi-agency coordination."

Noah Smith has a great piece called "The Build-Nothing Country," where he unpacks some of the dynamics that make it so expensive to build anything in the US. This line at the end, in particular, really struck me:

"Slashing the thicket of red tape that prevent development, and subordinating local interests to the needs of the nation itself, are no longer idle dreams — they are immediate necessities. If we insist on continuing to be the Build-Nothing Country, our once-mighty middle class will sink into a genteel poverty, and someone else will build the future on the bones of our civilization."

People generally have a difficult time thinking long-term, no matter how much they say they're long-term thinkers. I remember hearing this idea that the reason a year felt so long when I was a kid was because when you're 10 years old, 1 year is 10% of your life. But when you're 30, 1 year is 3% of your life. So it makes sense that as you get older, it feels like each year is shorter. It's because it is in relative terms.

When it comes to the capabilities of our civilization, people seem unable to appreciate how young the US really is. The US has been around for 246 years. The Roman Empire lasted ~1,000 years. We might think that our inability to build anything without exorbitant costs is just a frustrating administrative headache. But the reality is our inability to build things efficiently is a sign of civilizational decline. The Romans forgot how to build aqueducts. The Egyptians forgot how to build pyramids. We might not make it 1,000 years if we can't continue to progress in the way we build things.

The Axis of Building In The World of Startups

One of the best collections of impressive achievements with an emphasis on speed is Patrick Collison's list of "examples of people quickly accomplishing ambitious things together." In it, he mentions examples like Disneyland (built in 366 days), the Eiffel Tower (793 days), Javascript (prototyped in 10 days), or the iPod (290 days from conception to shipping).

When it comes to entrepreneurship, the lean startup methodology has been fairly common. The idea of rapid prototyping and iteration. "Move fast and break things." The important of speed comes as no surprise to the startup initiated.

In many ways, I think the speed of experimentation is what makes a startup one of the most effective mediums for innovation. But I think there's something to be learned for startups from the world of increasingly expensive government infrastructure projects.

In my wildly uninformed and anecdotally supported perspective, I would boil down the drivers of government inefficiency to two things: (1) complex web of stakeholders, and (2) ineffective money measurements.

Complex Web of Stakeholders

I've written before about the attempts to control your own destiny, and the role of dependencies in building a business:

"The more dependencies you introduce to your business, the more you're at the mercy of other people's narratives. In a world of naysayers, sad-sops, and storytellers (who are grumpy), look for those opportunities to grow organically, rely on yourself, and build with fewer people who are more bought into the vision. Don't be afraid of dependencies, but only depend on dependencies that are dependable."

Just like governments are riddled with different political departments, competing agencies, and combative constituencies, startups can increasingly become battlegrounds between the perspectives of founders, employees, investors, and customers. Amazon's customer obsession isn't just good marketing, its an act of prioritizing dependencies. "We're going to put our customer dependency first."

If you prioritize every investor, every kind of customer, and every employee then you'll quickly find that everything takes longer, and it's more expensive. One of the most common discussions I have with early stage founders is how to know where to focus their efforts with customers. If you want to sell to enterprise customers, then getting caught up serving SMBs can be death by a thousand costs that slow you down and make everything more expensive.

Ineffective Money Measurements

I've written over and over and over and over and over and over and over again and the importance of effectively measuring outcomes:

"There will always be the “move fast and break things” people who want to raise $100M every 6 months lighting money on fire as they go. And there will always be the bootstrapped worriers who look at VCs as parasites who ruin businesses. Neither of them will always be right or wrong. Cash, like any strategic asset, is a double-edged sword. It can be used effectively (even in large quantities) or it can impale you. The difference is whether you're decisive enough to dictate how you use it."

The US government, and governments in general, are terrible at effectively measuring how well they're spending their money. The bureaucracy and quid-pro-quo drive up costs everywhere you look. From healthcare to education and general quality of life, there are any number of data points to look at in articulating areas of decline in America.

While companies are typically more effective stewards of capital than the US government (low bar), there are still instances of inefficiency. I've written several times before about this quote from Bill Gurley:

"Never in the history of venture capital have early stage startups had access to so much capital. Back in 1999, if a company raised $30mm before an IPO, that was considered a large historic raise. Today, private companies have raised 10x that amount and more. And consequently, the burn rates are 10x larger than they were back then. All of which creates a voraciously hungry Unicorn. One that needs lots and lots of capital (if it is to stay on the current trajectory)."

Companies that have been built on a glut of capital have similar habits of the US government. Incentives around spending, shallow north star metrics, and complete lack of efficiency measurements. There is a host of lessons for startups to learn form these exceptional projects that have been built quickly, and often shockingly cheap.

AI's Impact On The Axis

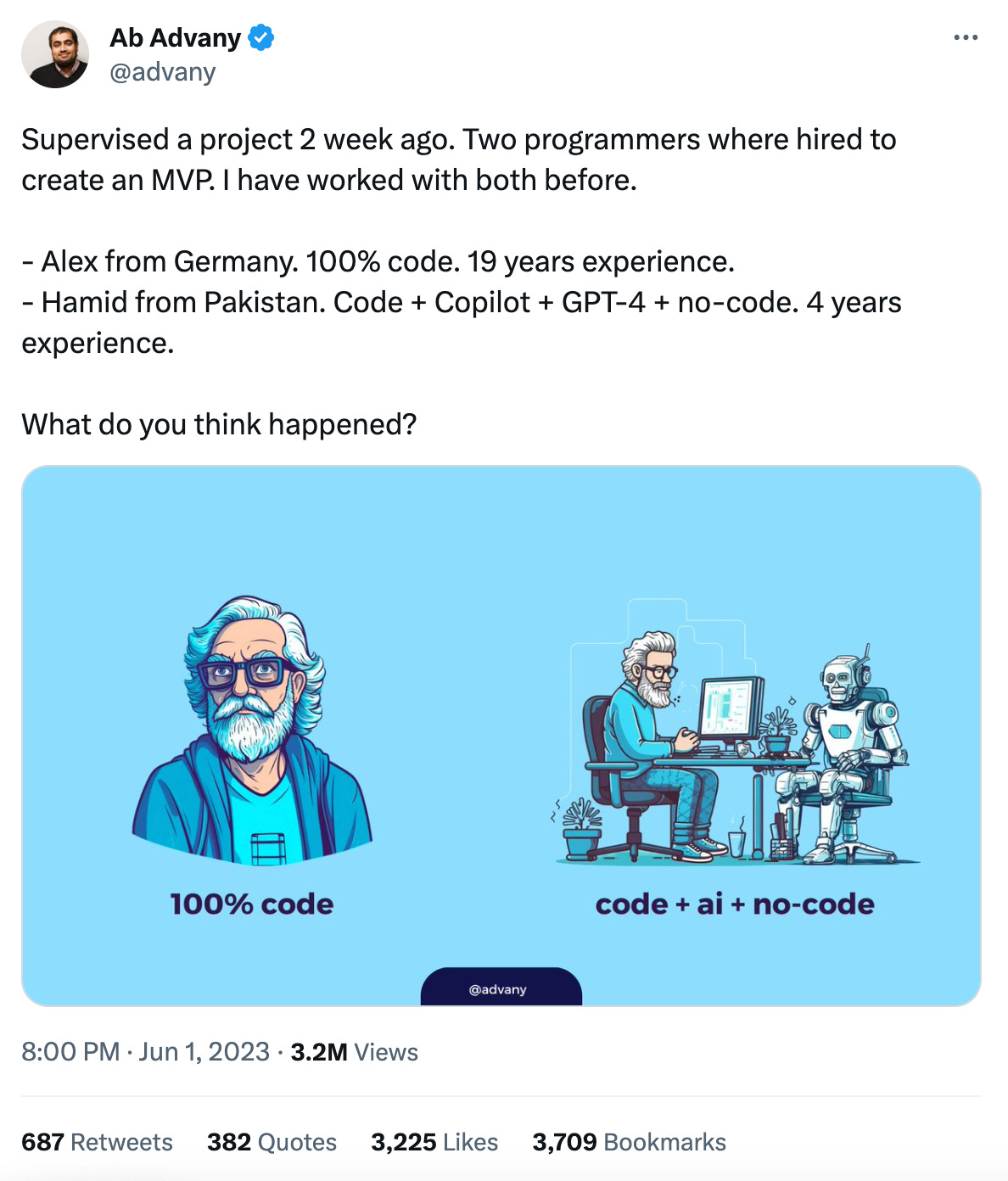

Final parting thought as I reflect on the axis of cost and speed. I think AI will present one of the greatest productivity unlocks we've seen in a long time. I came across this case study comparing a seasoned developer only writing their own code vs. a newer developer leveraging AI tools.

In the end, the code purist was going to be 13x slower, and 25x more expensive than the AI-enabled programmer. Granted, there are going to be complex applications that require more robust skillsets, and an AI-assisted output might just be too buggy to put in production. But that doesn't change the surface area of building that AI can address.

The best businesses in the long-run understand how to build an effective core flywheel to get things done. Finding the best tools (AI), the best measurements (efficiency), and the optimal timeline is a pretty unbeatable formula.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Good read. "Cash, like any strategic asset, is a double-edged sword. It can be used effectively (even in large quantities) or it can impale you. The difference is whether you're decisive enough to dictate how you use it."

Memo to myself: https://share.glasp.co/kei/?p=tMiEI8wp9JTjuuEaDuJW