This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

A few years ago, my wife and I got super into a BBC show called "Luther," about a police detective in London living on the edge, often confronted with sociopaths. One surprise while watching the show was the result, I realized later, of being an American. This cop would walk into what felt like ridiculously dangerous situations with no gun.

I'm used to American cop shows where any time there is even the slightest possibility of danger, they're going to have a gun. If this concept was more central to my post, I'd spend more time researching this, but in general I'm sure there is some term for the differences in the comfort levels of various culture's with different things, in this case violence.

So what got me thinking about this? I was asking myself, "what's an interesting analogy or story or example to illustrate the idea that something you think is a competitive edge isn't always as real as you think. And the only two examples I could come up with were both violent and from movies. 🤷♂️

The first? In Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, a rather large man challenges Butch to a knife fight. You'd think the size of this guy would be all the competitive moat he needs. But the moat turns out to be moot.

The second is a classic scene from Indiana Jones. Indy is met in the street by a talented swordsman, with a similarly intimidating moat. But Indy's response proves to be as nullifying to that moat as Butch's approach.

So let's talk about competitive moats, and particularly why, for a big part of the journey, defensibility is for dummies.

All That Matters

One of the things that has brought defensibility and competitive moats to the forefront of the conversation recently has been the newest wave of AI startups. When a whole swath of companies are building on the same open source foundation models, or as wrappers around ChatGPT, can they really be defensible in the long run?

I'm certainly one of those skeptics that worry about how well a company can compete when their underlying technology has the same nuts and bolts as every other product tackling the same problem. But when you look at what really matters, you start to feel like defensibility might just be for dummies.

In a great post recently, Evan Armstrong explains the core components of a business: (1) Create stuff, (2) Acquire customer to buy stuff, and (3) Distribute that stuff. He describes the impact that AI will have this way:

"The internet broke the third category of distribution, and AI is going to break the first one. Innovations like GPT-3, DALL-E, and other AI tools will dramatically decrease the cost of producing goods with a digital component."

So what does that leave? Customer acquisition.

The last decade or so of company building has largely revolved around cash burn. Companies have spent exorbitant amounts of money, and in almost (not every) case it has been after one pursuit: customer acquisition. Market share.

I've written before about some of these case studies that personified this era of (often irresponsible) spending:

"For a lot of people, ride-sharing was one of the original "Cash War" battlegrounds. There were a lot of competitors and the ones that stuck around were the ones that could fundraise most effectively. Uber and Lyft raced to raise more money, to spend more on marketing, to open new markets, and to attract more drivers.

And when you look at the history of capital raised the numbers are staggering and the difference is stark... Uber raised $25B to generate $17.5B in revenue. Lyft raised $5B to generate $3.2B in revenue.

In the case of Uber vs. Lyft? Cash as a weapon seems to have been an effective strategy. But cash as a long-term lasting moat? Doesn't seem like it. As recently as Uber's earnings call in February 2022 they spent a lot of time talking about strategies to reduce their CAC. If your CAC stays high even as you dominate a market you likely don't have a very effective moat."

There is a graveyard of companies who probably spent a lot of time reading about competitive moats, but never lived long enough for them to matter practically. If you don't have the money or time to build a castle, then your moat doesn't matter. And now, a lot of the things that investors could use to artificially inflate their belief in defensibility are much cheaper. Whether you're writing, coding, designing, or emailing, a lot of that stuff is pretty cheap now.

Back to Evan's post about AI:

"When AI automates content creation costs to zero, the effects will be far-reaching. More and more power will accrue in those companies that have novel acquisition methods that do no rely on any gatekeeper. In previous editions of this column, I’ve argued that “addiction will be the blood sacrifice required of consumers for businesses to win.” These tools will only exacerbate that dynamic."

Customer acquisition will be a unique and powerful battlefield as companies look to set themselves apart. That's why brand and reach will become more important than ever. In an era of automated creation, you'll need to be even more creative with how you get your stuff in front of people. I've said before that ChatGPT, as astounding as it is for a technical breakthrough, is an even more astounding distribution breakthrough.

However, as important as novel acquisition methods are, or even the ability to drive "addiction" in Evan's words, your kingdom is not simply your acquisition funnel. You build a kingdom around people, so having an acquisition strategy is the only way to merit a kingdom. But when you actually build the castle, it has to be more than that.

The Kingdom Comes First

For anything in the long run to matter, you have to build something worth defending. One of the best frameworks I've seen for what you're building is around "capabilities." This idea was presented to me in a post by Rick Zullo at Equal Ventures. In it he introduces really interesting concepts like moat trajectory, and others, before explaining the practice of "building capabilities" this way:

"Capabilities (referred to as “powers” by some, including Helmer’s immensely impactful book 7 Powers) are the intangible assets that you have developed as a business that enable you to operate more effectively and earn returns above others in the market. Ultimately these are the engines of your competitive advantage, determining the persistence and scope of your moat. While these may never appear on a balance sheet, they are the single most valuable asset of a company. Identifying how to build that intangible asset is core to a company’s business model and requires deliberate planning to unlock."

The biggest recipe for building a competitive moat in the long-term are the business capabilities that you build early on. And here's an idea that may feel blasphemous in the current VC religion of "profit, profit, profit," but burning cash can actually be an effective capability. The last few years where dozens of companies have lit atrocious amounts of money on fire, their cardinal sin wasn't burning money. It was burning money ineffectually.

There are so many arguments for cash burn in pursuit of scale. The logic goes, "if I can spend $X (CAC) to acquire a customer that will spend $Y (LTV) then its worth it as long as $X < $Y." That fundamental idea is sound. The breaking point is whether customers will actually stick around long enough for $Y to exceed $X. Uber's problem is that they can't stop spending $X, so their only capability is spending money, not necessarily keeping customers.

Keeping $X low is a function of novel acquisition methods. Keeping $Y high is a function of stickiness. Stickiness can come from structural advantages, like long-term contracts, or it can come from optimize customer experience. Customers stick around when you have the best products that continue to improve at high velocity.

Elon Musk's perspective revolves around this idea of product velocity, or what he refers to as the "pace of innovation."

“First of all, I think moats are lame. It’s nice, sort of quaint in a vestigial way. If your only defense against invading armies is a moat, you will not last long. What matters is the pace of innovation. That is the fundamental determinant of competitiveness.”

My point is not that competitive moats don't mean anything. Instead, it's a combination of them being inadequate alone (Elon's point) and the reality that in the earliest days startups "a priori may be easy to copy or build." Fat Baby Funds expounds on the idea of the unavoidable existence of danger this way:

"The reality is that people lie to themselves to make themselves feel safer in their investments. Having a castle without a moat is scary. Thinking a moat keeps your castle safe is more dangerous. Putting your faith into a business and trusting that it will protect itself without a durable competitive advantage is scary, but that is the reality of investing in young innovative businesses."

Danger is the reality of building an early stage business (and early can be used the same way my 85-year old grandma uses the term "young," it's all relative). Trusting in a fuzzy view of your "competitive moat" won't keep you safe when you're in a fast-paced, rapidly-changing environment. Instead, to Elon's point, a big focus should be on the pace of innovation.

Vying For Velocity

I would argue that how "young" a company is comes largely as a function of how quickly they're changing (cue the ship of Theseus analogy). A company that is fairly stagnant can still do well, but they're not as young, and therefore pace of innovation matters less than hunkering down. Apple and Microsoft were both founded in the mid-1970s. But I see Microsoft as a young company, and Apple as... not.

Now, I'm no public analyst. So lot's of people would fight me on this. But just from my shallowly informed view, Apple largely rides the benefits of a series of near-monopolies when it comes to things like the App Store, iOS, and Apple Pay.

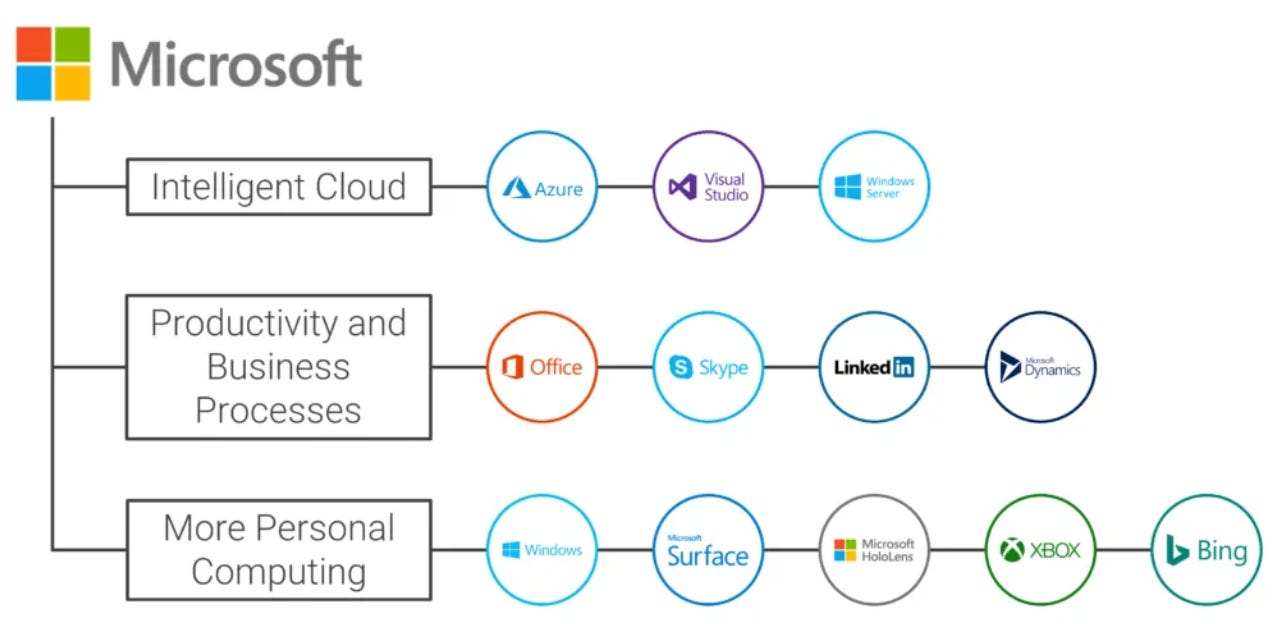

Microsoft, on the other hand, feels like a company that has evolved dramatically over and over again (granted, they have plenty of their own monopolies). The transition from shipping physical disks to universalizing Windows to the Office suite to Azure, and now while they're old in years, but young in spirit, we get to watch them go through an AI evolution with OpenAI. Sometimes it feels like watching your elderly uncle reinvent himself. But it's still transformative.

You can visualize the Microsoft product suite, and you start to realize how extensive it is across not only Windows and Office, but Xbox, Linkedin, GitHub, Bing, and more.

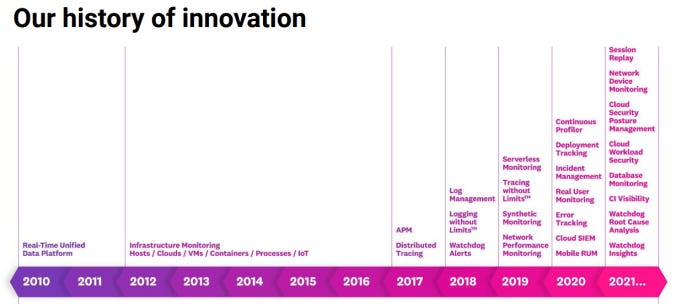

Most of the very best companies have these same types of visualizations to demonstrate their product velocity. They ship a huge amount of product extendability to ensure customer satisfaction and stickiness (e.g. that $Y stays as high as possible for as long as possible.)

When I think about core pillars of the software world, like Salesforce, ServiceNow, or Adobe, they've all extended their product capabilities pretty dramatically. In a great post on the future of enterprise applications, Matt Slotnick uses Salesforce as an example, and explains their product extendability this way:

"Salesforce has long understood that their core value and defensibility is that businesses are inherently customer centric, and the most valuable data at a company is the data related to how they sell to and serve their end customers. This has led Salesforce to be a system of record for managing data on arguably a company’s most important asset.

Data has gravity, and this system of record both commands immense value on its own, but also creates influence on all other systems within an organization. Other systems need to play well with Salesforce, because if they don’t, they’re unlikely to be adopted. This makes Salesforce the System of Record. They have leveraged this to build a number of other large businesses in addition to sales — namely marketing cloud, service cloud, commerce cloud."

One company that hasn't as successfully extended itself is Workday. That doesn't mean that Workday doesn't have any competitive moats, but it doesn't seem to have a rapid pace of innovation. As a result, you have to start to really evaluate the longevity of any existing advantage they have.

The longevity of those competitive moats can be the difference between life and death. In a newsletter from Permanent Equity a few years ago, they made this great point about the "saving grace" of competitive moats, and how it can only go so far:

"Moats are routinely discussed in a static sense, as if they exist in some form or fashion for most businesses. But the facts simply don't bear this out. Indeed, the facts show that every business, year after a year, decade after decade, has a non-zero percentage chance of extinction. Companies have a high failure rate in their first three to five years. Then the challenges plateau. Averaged across industries, a business in its 25th year has roughly the same probability of dying as it did in its 10th year.

So When Do Moats Matter?

There is an ocean of thought processes around competitive moats and what makes a definitive advantage. Great books have been written, like Competition Demystified or Moats and Marathons, as well as some great work from folks like Michael Mauboussin. Other folks have introduced frameworks for "new moats" like building systems of intelligence, rather than systems of record.

Counterpoint Global has put out a list of dozens of companies with what they refer to as "wide moat businesses." Each of them could be an interesting case study, and there's no doubt many of them have classic competitive advantages.

One of the biggest prophets of competitive moats is Warren Buffett himself:

"If you are evaluating a business, the number one question you want to ask yourself is whether the competitive advantage has been made stronger and more durable. That’s more important than the P&L for a given year."

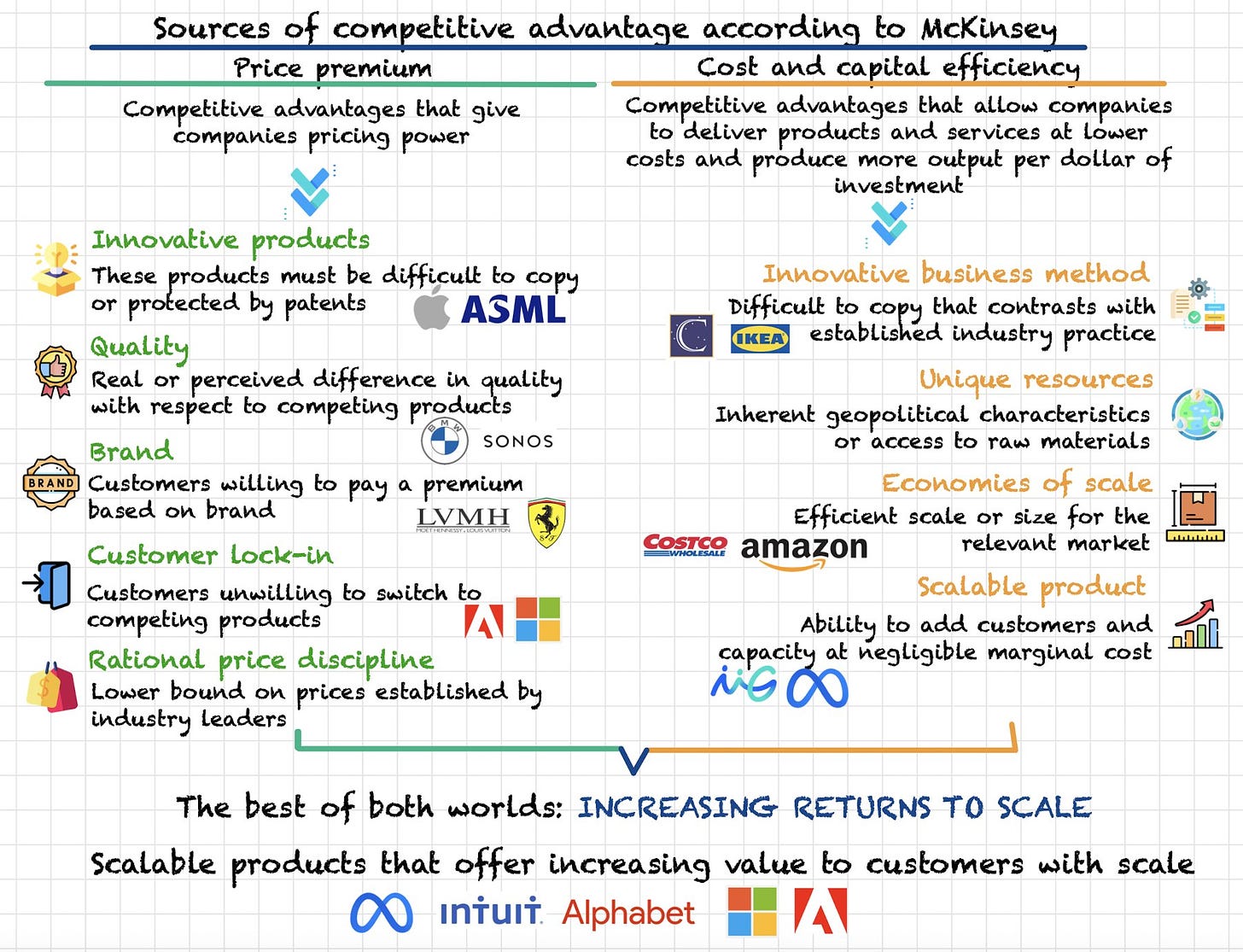

Elad Gil recently put together a pretty extensive list of typical moats including things like network effects, platform effects, product velocity, complex sales, regulation, and scale. Similarly, McKinsey has a broad framework for the sources of competitive advantage:

There's a lot of interesting literature here, all of it with merit. For my perspective, I agree with Elon Musk and Fat Baby Funds (boy, that's an interesting sentence, huh?) I think that competitive moats can be powerful. But if you believe that they're enough to save you from an ever-increasing pace of innovation in every category, I think you're delusional.

Going forward, the very best companies will be those that have nailed a very specific pain point for a very specific type of person. They'll have formed a novel acquisition method for bringing those customers as cheaply as possible, and they'll have the product velocity and quality to keep those customers around for as long as possible.

Nailing that equation in the early days opens you up to let more natural competitive moats get built around your business. But if you run out of cash, or time, or talent before you can solidify that core equation? Your moat becomes moot.

What Does This Mean For Venture?

I haven't touched as much on the implications for venture here, other than the types of investing I think most people should be focused on. But one interesting takeaway from a conversation with a VC friend of mine is this distinction between whether a particular venture fund is building a fund? Or a firm?

A fund is how you generate the most carry with the fewest people, you're just optimizing the mechanism. A firm, on the other hand, is (1) generating exceptional returns, but also (2) building enduring enterprise value.

Enterprise value has to come from having a compounding advantage. A fund can ebb and flow in its quality. A firm has value creation that is replicable. Blackstone is one of the best examples of this, and one that I return to often. They've built a repeatable mechanism for creating value (a firm), not just a strategy for a particular asset class (a fund).

"[We] keep challenging ourselves with an open-ended question: Why not? If we came across the right person to scale a business in a great investment class, why not? If we could apply our strengths, our network, and our resources to make that business a success, why not? Other firms, we felt, defined themselves too narrowly, limiting their ability to innovate. They were advisory firms, or investment firms, or credit firms, or real estate firms. Yet they were all pursuing financial opportunity."

Venture funds could not only do a better job of investing in companies with rapid pace of innovation, and high quality formulas for translating customer acquisition into customer value, but they could also do a better job of articulating that for their own businesses.

Thanks to Eugenia Lustgarten, Sebastian Duesterhoeft, and David Haber for jamming with me on this topic.

What I'm Reading

I'm trying something new this week. While I’m proud to have consistently written a weekly post for over a year now across a lot of topics and sources, it often comes as a surprise to people that I don't consume nearly as much content as I wish I did. I don't read as many articles, listen to as many podcasts, or finish as many books as I wish I did.

I've tried every reader app there is, I've tried subscribing to everything and forcing myself to clear my inbox of my various newsletter subscriptions, I've even tried printing things out hoping to clear them off my desk. Nothing has worked.

The only reading I do is often the "just-in-time" resources I need to read for my post each week. While that has been a huge ancillary benefit of writing weekly, it also means that my reading is very narrow (as narrow as that week's topic).

So, as a way to try and expand my reading I've decided to include this new section at the end of each week's post. Throughout the week, I save links to articles that I think look the most interesting to me, and then read them as part of writing each week's post. I’ll only include it if I’ve read it. We'll see how well this works for me:

Rekindling US productivity for a new era by McKinsey

The Build-Nothing Country by Noah Smith

What Is ChatGPT Doing … and Why Does It Work? by Stephen Wolfram

The AppetiZIRP by Packy McCormick

We’re Selling Entrepreneurship Short by Bryce Roberts

Bonfire of the consultancies by Lionel Barber

To Save America, Restore Our Frontier by Joe Lonsdale

How to Trick Investors & VCs by OnlyCFO

Infinite Games by Jack Raines

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

The best article I've read for a month.

My learnings:

"Customer acquisition will be a unique and powerful battlefield as companies look to set themselves apart. That's why brand and reach will become more important than ever. In an era of automated creation, you'll need to be even more creative with how you get your stuff in front of people.

"Identifying how to build that intangible asset is core to a company’s business model and requires deliberate planning to unlock."

"Going forward, the very best companies will be those that have nailed a very specific pain point for a very specific type of person. They'll have formed a novel acquisition method for bringing those customers as cheaply as possible, and they'll have the product velocity and quality to keep those customers around for as long as possible."

Memo to myself: https://share.glasp.co/kei/?p=WDNfccPkLCji5yvd3jBF