Institutionalized Belief In The Greater Fool

Or Why Hopin Is Everything Wrong With Venture Capital

This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

If you've been reading my writing for a while, you'll know that I'm far from a venture capital stan. I'm a pragmatic observer of my own craft, and as much as you can learn from success, there is also a lot to be learned from bad behavior.

Those are just a few of the pieces where I've reflected on the excess and irresponsibility of venture capital. But few case studies better sum up my grievances with various aspect of the venture capital industrial complex than does the story of Hopin.

What's Hopin'in?

Get it? Like, "what's happenin'?" Alright. Moving on.

In case you haven't seen the news, this is the best overview I've read. For the details, I'll summarize it real quick. In 2019, Johnny Boufarhat founded Hopin, a virtual events platform, in what may be the most well-timed founding ever.

COVID happened, and the company exploded. From November 2020 to August 2021, the company's valuation went from $2B to $7.7B. The company also reached $100M+ of revenue, serving 100K+ organizations running 15K+ events per month! Across 4 rounds in 14 months, the company raised ~$1B in funding! Boufarhat, the CEO, wasn't without his own enrichment. Over the course of those rounds, he sold ~$200M of secondary.

And then, wouldn't you know it, COVID restrictions started to lift, people could travel again, and Hopin's usefulness dropped from 15K events per month to 158. After several rounds of layoffs, Boufarhat announced he was stepping down and the company's flagship virtual events product was being sold to RingCentral for $15 million in cash with $35 million in potential performance-based earn outs. The acquisition was barely a footnote for RingCentral, with the CFO saying they “expect the acquisition [of Hopin’s assets] to have an immaterial impact on our revenue and expenses in 2023."

Man, oh man. So much to unpack here.

Hopin has joined some prestigious names in the hall-of-fame for capital destruction:

WeWork? Raised $22B in equity + debt at a peak valuation of $47B. Currently has $200M in cash, and a market cap of $431M. Recently announced their doubts about the company's ability to continue as a "going concern."

Peloton? Raised $1.9B at a peak valuation of $45B. Currently has $870M in cash, and a market cap of $3.4B.

Lyft? Raised $4.9B at a peak valuation of $20B. Currently has $638M in cash, and a market cap of $4.4B.

Quibi? Raised $1.8B. Currently has $0M in cash, and a market cap of $0.

Bird? Raised ~$1B at a peak valuation of $2.5B. Currently has $6.8M in cash, and a market cap of $22M!! 😱

Don't even get me started on any other SPACs (I'm looking at you Mr. Next Warren Buffett).

Granted, the $1B that Hopin raised didn't entirely disappear. There's still ~$400M, some of which the company might return to investors. And Hopin didn't sell entirely. They had previously acquired a live streaming business that is now the main product, with a valuation of ~$400M (a 95% decline from that $7.7B high).

But, like many of the examples of excess I've unpacked before, there's plenty to learn about some of the things that can be wrong with venture capital.

The First Principles of Human Behavior

The first that I came back to is how unsurprising it feels like this is. Just about everyone working in startups has had some version of this experience: "this doesn't make sense, does it?"

Crypto mania. Billion-dollar valuations for pre-revenue companies. Investors branding themselves as "micro mobility investors." Even much of the current hype in AI. All of it leaves you scratching your head, trying to understand how that can make sense.

In the case of Hopin, you see a lot of instances of people being surprised. Here's a couple examples:

"Where things went wrong was behavior changed, consumer behavior changed in a way that the company didn't predict." (Former Employee)

"Nobody expected virtual events to go away as fast as they did.” (Former Employee)

But like... why not? Did anyone really, genuinely believe that life would forever be trapped lockdown-style? I think often of this tweet from early in 2020:

Investors are very much in the business of "dreaming the dream," but too often we have investors that assume the dream is supposed to be a fever dream.

Instead, the reality is that human behavior changes very little, and when it does it happens very slowly. More often than not, you can see these changes coming in the future. You may not appreciate the gravity of the future, but you can see trends like cellular bandwidth speeds acting as a clear catalyst.

But when things don't feel right (e.g. will the vast majority of people really want to be doing virtual events forever?) its probably because they're NOT right.

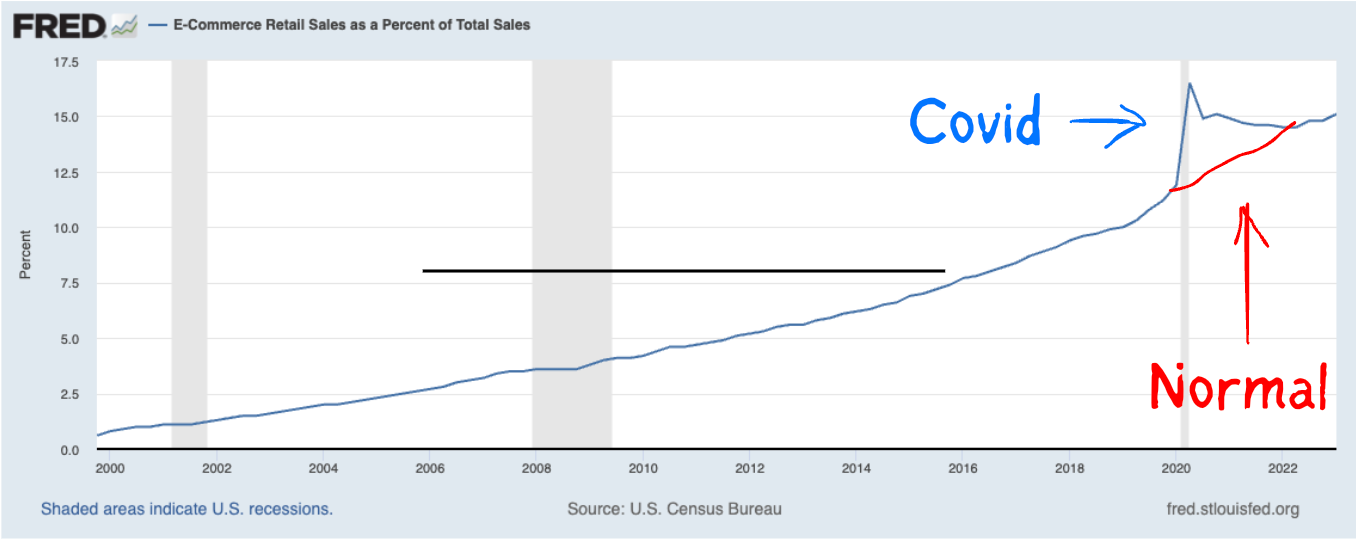

Ecommerce is another example of something that people assumed would be changed forever. COVID had unlocked the online world, and we were never going back to normal. But the reality is that change has an almost gravitational force, and its very difficult for anything to make it happen more quickly or more slowly.

It's almost incredible how right back on track we got with something that has been a pretty fundamental tailwind. But it's almost as if the universe has commanded that change will roll forward at such-and-such a pace, no more, and no less.

During COVID, when investors whipped themselves into a frenzy, they would have done well to step back and think "is this change based in something that feels real? Something that can stick around?" And most people would have probably struggled to articulate it as relevant in the future. At least relevant enough to justify a $7.7B valuation. Which brings me to my next point.

The Reality of Capital Destruction

A common refrain in the world of startups is that 90% of them fail. It's just the cost of doing business. In other words? You have to crack a few eggs to make an omelette. And I agree with that. But there is the natural rate of failure, and then there is what most people call "unforced errors." Things that you look back on and say "it didn't have to be this way." That idea is perfectly summed up by this meme.

A piece came out in the Wall Street Journal this week entitled "Startups Are Dying, and Venture Investors Aren’t Saving Them." In it, my friend, and reliable critic, Hunter Walk, described the funding environment that we're facing:

"As the market changed, investors wanted to see evidence of dollars over user traction, making it difficult for [companies] to raise money. The investing mania that ended early last year has added to the pile of startups that are now shutting down as fundraising prospects dwindle. What we have right now is a perfect storm resulting in more than usual shutdowns."

Shutdowns are normal. But the whiplash that investors have wrought against founders is leading to "more than usual shutdowns." In other words? An unforced error.

Too much capital can cause a myriad of problems. For one, too much capital is typically driven by too many investors. And in the case of Hopin, that meant nobody was doing their homework:

"'After the first few rounds, when it got crazy and VC FOMO kicked in, it began to feel like ‘dumb money’ — even though it was coming from highly credible funds. They didn’t do due diligence and they didn’t inject governance provisions,'”' one early investor [said]. There were also so many VCs keen to invest in Hopin that none ended up with an influential stake."

What you get is far from an ecosystem of thoughtful investors attempting to make wise capital allocation decisions, and instead get the closest humanity may have come to "a thousand monkeys in a room with a typewriter," except instead of typewriters they have checkbooks.

When you step back pragmatically, and consider Hopin's prospects, you can do some simple math. When Hopin raised at $7.7B, the company had supposedly gone from $20M ARR in November 2020 to $100M ARR in August 2021. Investors in that round were maybe underwriting to a 3x return given the high valuation, so you're trying to dream the dream of how this company becomes a $20B+ company.

Cvent, a comparable company in the events space, went public in December 2021 with $518M of revenue at a market cap of ~$4.6B, ~8.8x revenue. At a comparable multiple, Hopin would have had to generate $2.3B+ in revenue; 23x growth. Assuming a 5-year hold period for those later stage investors? That would have to be one of the most incredible growth trajectories ever. And to believe that was possible, not just for any exceptional company, but a company that seemed uniquely tied to a really specific COVID trend? Idk.

What this leads to is a very bad reputation for investors. Most recently, a reputation that is branding some investors as "predators."

Venture Predators

In May 2023, Matthew Wansley and Samuel Weinstein published a paper entitled "Venture Predation," where they coined the phrase "venture predators," though they used it to refer to startups, not VCs. The idea they explored is the ability for venture-backed companies to leverage venture dollars to engage in predatory pricing. They can charge exorbitantly (even unsustainably) low prices in pursuit of market share.

Earlier this year, I wrote a piece called "VC Contagion," where I talked a lot about VC subsidies. The concept is effectively the same. Here's how I explained it:

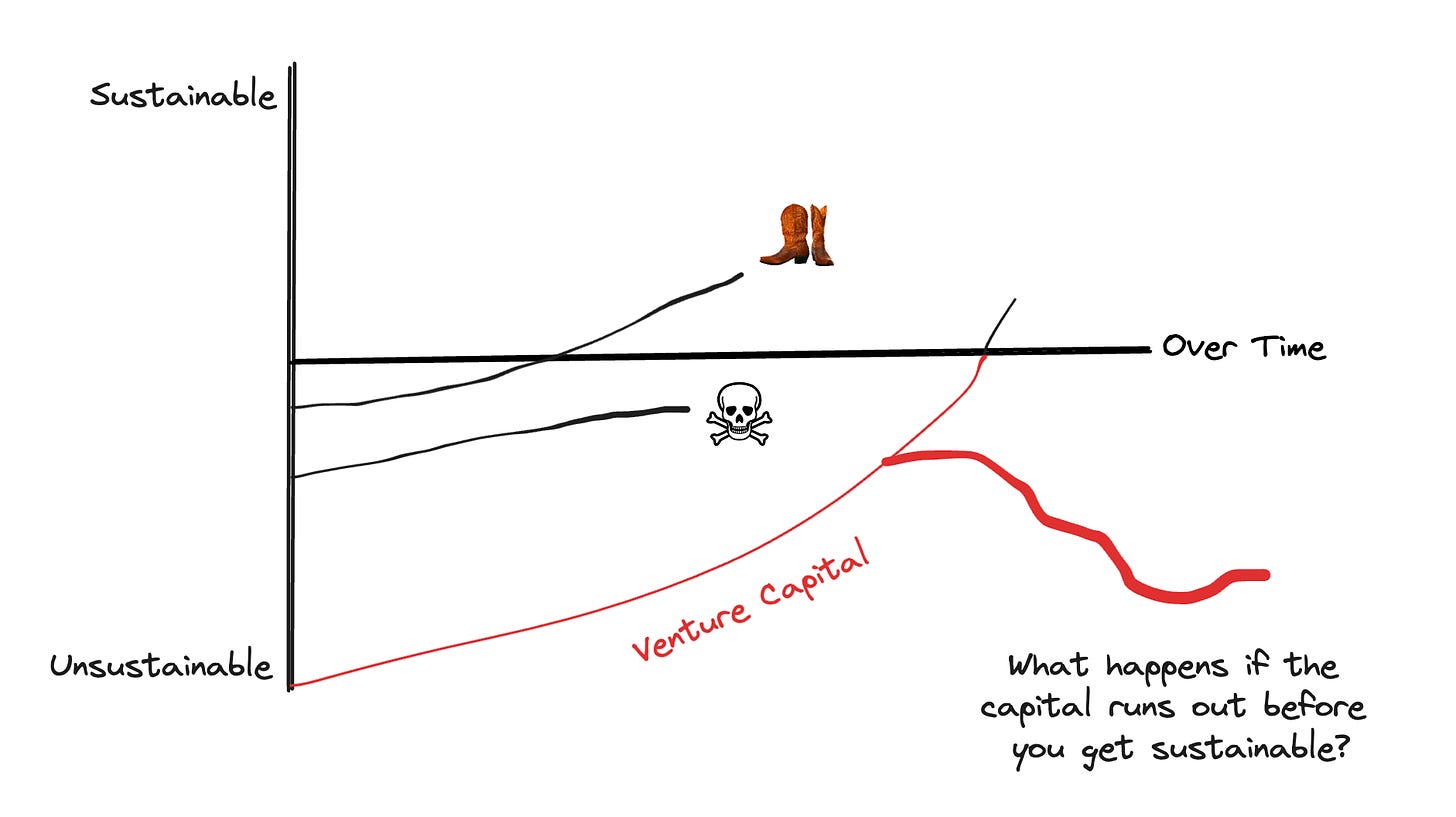

"Venture capital enables the perpetuation of unsustainable models in favor of eventual scale. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The runway to experiment has been critical for any number of businesses. But any good thing taken to excess can become problematic. The same is true with capital."

Venture capital is meant to enable companies to do unsustainable things in pursuit of scale that will eventually enable sustainability. But what if sustainability never comes?

In the piece, Venture Predation, the abstract contains a gut-punching line:

"Critically, for VCs and founders, a predator does not need to recoup its losses for the strategy to succeed. The VCs and founders just need to create the impression that recoupment is possible, so they can sell their shares at an attractive price to later investors who anticipate years of monopoly pricing."

Ohmygawd. Talk about saying the quiet part out loud. This gets to the crux of the Hopin question I raised at the end of the last section.

How can investors believe a company that went from $20M to $100M ARR in 8 months could eventually get to $2.3B in revenue? They probably didn't! They just had to believe that someone ELSE could believe that something like that was possible. This is literally an academic representation of "passing the bag."

One of the most un-dealt with ramifications of a 13-year bull market is the institutionalized belief in "the greater fool." People can make money, not because a business is sound, but because there is always someone else down the line who will buy you out. And that was true for 10+ years!

Whether you're the CEO of Hopin selling $200M in secondary, or a founder pitching a $47B valuation for WeWork, or investors giving Quibi $1B+, you're probably not buying into pragmatic decision making and capital allocation. You're buying into the institutionalized belief in a greater fool. But no one will say that out loud. They'll reenact a scene right out of Margin Call.

A Hesitant Case Study To Conclude

I debated leaving this part out because I'm not sure I believe it. So consider this a mental exercise, not a statement of fact.

I think Stripe is an exceptional business, and one that has produced not only very good products, but a powerful culture, countless exceptional operators, an incredible example of the power of documentation, and an awesome book publishing operation to boot.

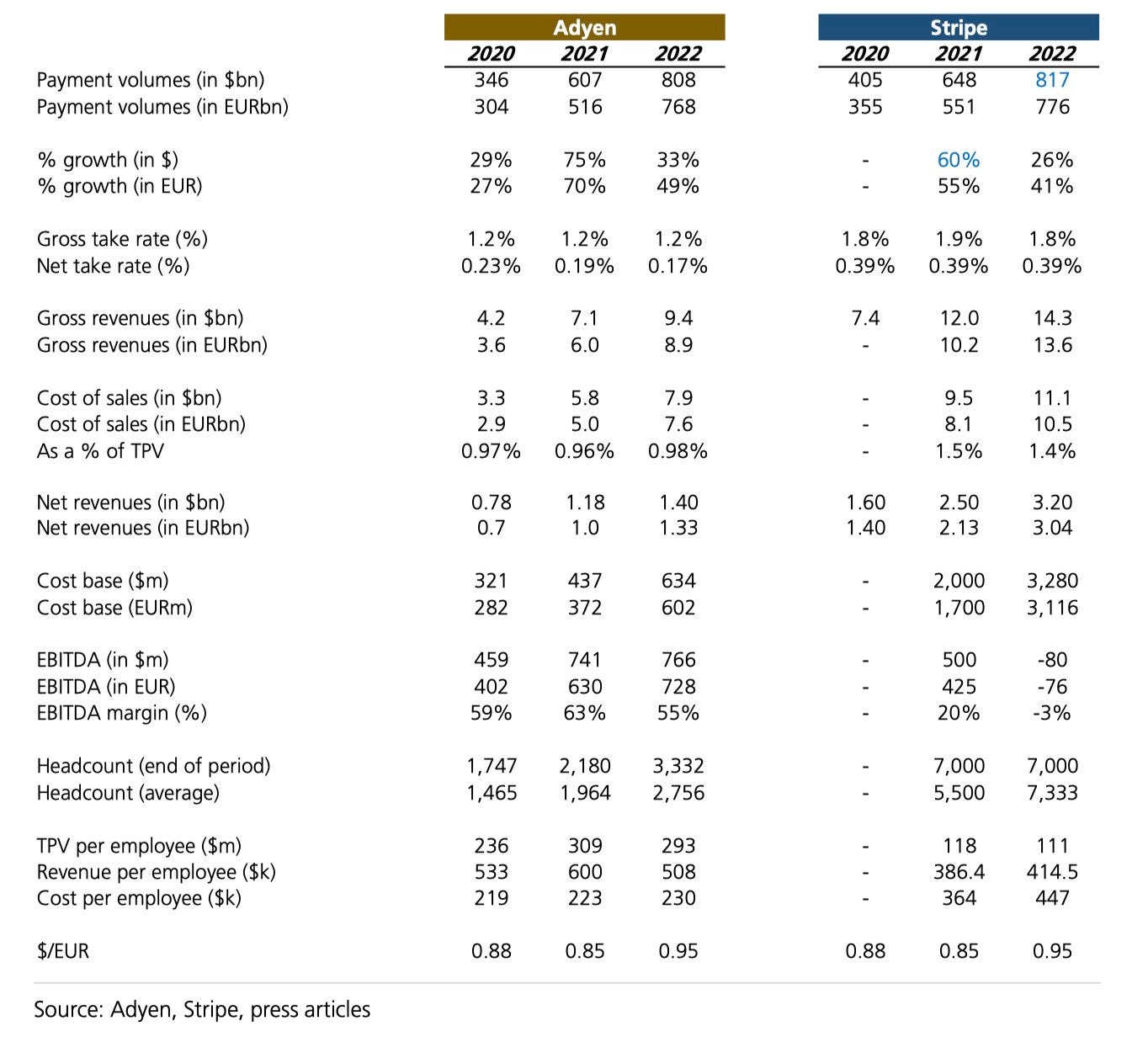

But recently I saw a side-by-side comparison of Stripe vs. Adyen that stuck with me:

While Stripe and Adyen are at similar scale of payment volumes (~$800B), Stripe has a better take rate (1.8% vs. Adyen's 1.2%). Stripe also has a better gross margin at ~22% (vs. Adyen's 15%). However, profitability is where these two businesses are in dramatically different places. On $1.4B of net revenue, Adyen is generating $766M of EBITDA (54% margin). Stripe? Negative $80M EBITDA on $3.2B of net revenue.

Now, again. I don't think this means Stripe is a bad business. Far from it. But what I'm exploring is this concept that the institutionalized idea of the greater fool is a product of the 13 year bull market that started in 2009 (if you don't count the temporary drop at the beginning of COVID). And it's interesting to me that Adyen was founded in 2006 vs. Stripe was founded in 2010.

I'll say it one more time. I do not think Stripe is a bad business. But I think businesses whose operating model and valuation mechanisms were crafted between 2009 and 2021 all have a fundamental flaw of believing that the institutionalized belief in the greater fool will allow the next investor (the bag holder) to hide a multitude of sins. Though, there are some notable exceptions, like Datadog and Airbnb, that I think have healthier P&Ls.

I'm a fervent believer in the need for technological progress and rapid change. And I believe that venture capital is an overwhelmingly net positive force in the innovation necessary to drive that progress and change. But venture capital, as a discipline, runs an existential risk of invalidating itself by becoming institutionally what crypto is colloquially. If venture capital is just about "[creating] the impression that recoupment", then its no better than the pump and dumps of the crypto bros.

We need to be better, both as venture capitalists, and as founders. We don't need a more fervent belief in a greater fool. We need a stronger commitment to building businesses of which we would NEVER want to sell a share.

People want to idolize Warren Buffett's success, but never his practices. And what are his two most poignant practices? (1) Get rich slowly, and (2) never sell a share of Berkshire Hathaway. I recognize the need for liquidity, both for founders trying to live their lives, and VCs trying to generate returns for LPs. So none of this is a blanket statement of good or bad.

But it is a statement against excess. Too many people want to get rich quickly, and to do it by selling to the greater fool. And that is a problem.

Thanks to Jason, Rahul, and the rest of the Research Fellows for jamming on this topic with me yesterday in our sync for Contrary Research.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

i want to print this one out, cut it up into little pieces, and snort it

I remembered your past quotes, "Venture capital enables the perpetuation of unsustainable models in favor of eventual scale. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The runway to experiment has been critical for any number of businesses. But any good thing taken to excess can become problematic. The same is true with capital." A good read as always.

Memo to myself: https://share.glasp.co/kei/?p=bjs1jBvXd9kf9Oa8hVEI