This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Power has, historically, been able to operate in a vacuum. Whoever has the largest army, or the most resources can largely control the world. "Whoever has the gold makes the rules." I'm no historian, but it seems that for the majority of human history there was a fairly limited role for "personal preference" to play in how things are governed.

Whether its the Magna Carta, or the Declaration of Independence, there are points in time when people have thrown off the top-down preferences in favor of their "own will." Perhaps one of the greatest demonstrations of the inspired many against the powerful few comes from A Bug's Life.

Power is such a poignant force that it becomes increasingly difficult to believe that the top-down influence is, in any way, avoidable. A lot of people give up on ever changing anything because the powerful elite will decide everything, whether we like it or not. But I think the reality is a lot more decentralized than you might expect.

I've written before about a quote from Sapiens that describes the power of collective agreement in the long-tail:

”There are no gods in the universe, no nations, no money, no human rights, no laws, and no justice outside the common imagination of human beings. Whether or not something is true doesn’t impact whether you believe it.”

That is, I think, an important reality about most of our institutions and systems. We are governed the way we're governed because we agree to it. People have power over us only inasmuch as we allow them to. But that doesn't stop a generation of would-be kings from asserting their influence.

The same is true in venture. VCs often consider themselves "king makers," able to tip the scales in one direction or another. The breadth of their royalty doesn't come from any God, or divine right, but simply the size of their coffers.

The Kings Of Venture Capital

Over the course of the bull market from 2009 to 2021, venture capital has grown quite far from the "cottage industry" of old. More capital meant more spend, more spend meant bigger operations, and bigger ambitions. The bigger the outcome, the more justification there was for more capital. How do you fight capital? With more capital. (Right? Cause fight fire with fire has been a staple of the firefighting industry for decades.)

No firm has more represented this king making perspective than SoftBank's $100B Vision Fund that launched in 2017.

Firms like Sequoia felt forced to respond to the Vision Fund with their own $8B global growth fund, their largest fund ever.

And the king making wasn't subtle. Around the launch of the Vision Fund, SoftBank was very clear about their intentions to invest in Uber, who was still private at the time. But during negotiations, Masa explicitly said (in effect) "I want to invest in Uber, but I could also want to invest in Lyft." If you don't take money, I'll go across the street and give it to your enemy.

And don't get me wrong; capital can absolutely be a powerful differentiator in enabling a winner. There's a whole discussion on what a moat is, and how capital can strengthen and accelerate a moat, though its hardly a moat by itself. But that doesn't stop the Kings from trying to king make.

The slew of Vision Fund failures should be a strong indicator of how badly that strategy can fail. In May 2023, the Vision Fund posted a $39B loss. But maybe its the function of a fund strategy. What happens when a company is king made? Surely its difficult to fight against when a king asserts itself, right?

Wrong.

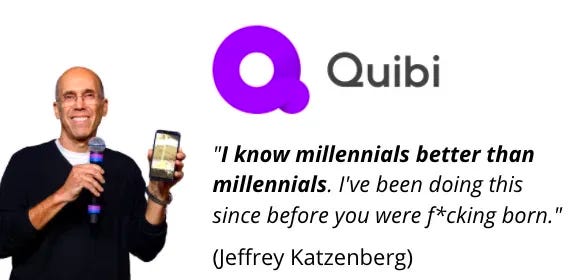

There have been few attempts at king making as massive as what Jeffrey Katzenberg tried to do with Quibi, starting in August 2018. I've written before about this exceptional tale. The company raised $1.7B, and built their mobile-only media company. The sheer hubris with which Katzenberg asserted his king-ness was akin to an actual king screaming into the void: "It is my divine right to rule!"

But after 8 months live, the app shutdown to much humming and hawing. The king was no king after all. So what happened? What was missing?

The Role Of Taste Making

What Quibi failed to recognize was that media companies like Disney or Netflix don't have divine right to entertain us. They wrack up billions in revenue entertaining us because we want them to. Everyone involved has tastes, and when someone comes along expecting to assert their tastes on you, they'll find themselves disappointed, and probably at least a little bit embarrassed.

Venture capital has been busy focused on the king making capabilities of capital, but they've lost sight of something important—there aren't enough startups to justify all that capital. But why is that?

Because (1) there aren't enough people building things that people truly want, and (2) there is only so much attention (time, energy, disposable income, corporate spend) that people have to give.

There is a finite amount of "taste" in the world. A lot of brands have thrived because there are surprisingly big niche markets, like mushroom foraging, that can sustain a certain amount of value creation and capture. But the biggest misallocation of capital is the limited understanding of taste—what do people actually want?

Controlling The Memes Of Production

Memes are such a fascinating cultural currency because their impact has become tangible. Whether its sending GameStop to the moon, or smashing the stock of companies like Eli Lily and Bud Light. Whether you agree with the underlying sentiment, or not. There is legitimate power in those memes. Memes have enabled more decentralized influence than any cryptocurrency.

Trevor Noah gave an interview where he was asked whether Dave Chapelle crossed the line with his comedy special:

Trevor Noah: "[That question] puts me in a position where I have to choose 'a side' when I think the matter is a lot more complex than that. I think everyone is defining the line for themselves."

Lesley Stahl: "No, society defines the line."

Trevor Noah: "You see what you're saying, 'society has decided.' But America is clearly divided in that half of society has said 'No, Dave Chapelle, we love what you said.' So if half of society is saying that he's right, and half of society is saying that he's wrong, then that means that there is no line. Society is seeing the line from two different sides."

I think the reality is even more complicated than that. Every person represents a complex web of preferences, interests, incentives, and in-groups. The world is filled with a complex psychology; more complex than perhaps its ever been. Memes, and culture wars, and TikTok—these are all just windows into the complexity.

Therefore, What?

In a world where capitalists are primarily concerned with building kingdoms, they're missing the point of what their capital is meant to create. People are so dramatically uninterested in monolithic decision makers dictating their tastes. Recently, I learned that the most watched TV episode of all-time is the final episode of M*A*S*H in 1983. And most of the highly watched TV shows are all from the 70s and 80s. Why? Because people still had a dramatically limited selection of shows to choose from, so most people were watching the same thing. But that’s not the case anymore. People contain multitudes, maybe more today than ever before.

I often see investors, especially public markets, and value investors, spend a LOT of time thinking about psychology. But the primary focus of that psychological exploration is focused inward; "how do I avoid making bad emotional decisions?" Venture capitalists are supposed to "see the present clearly." Part of that is understanding group psychology. Why do people feel the way that they feel?

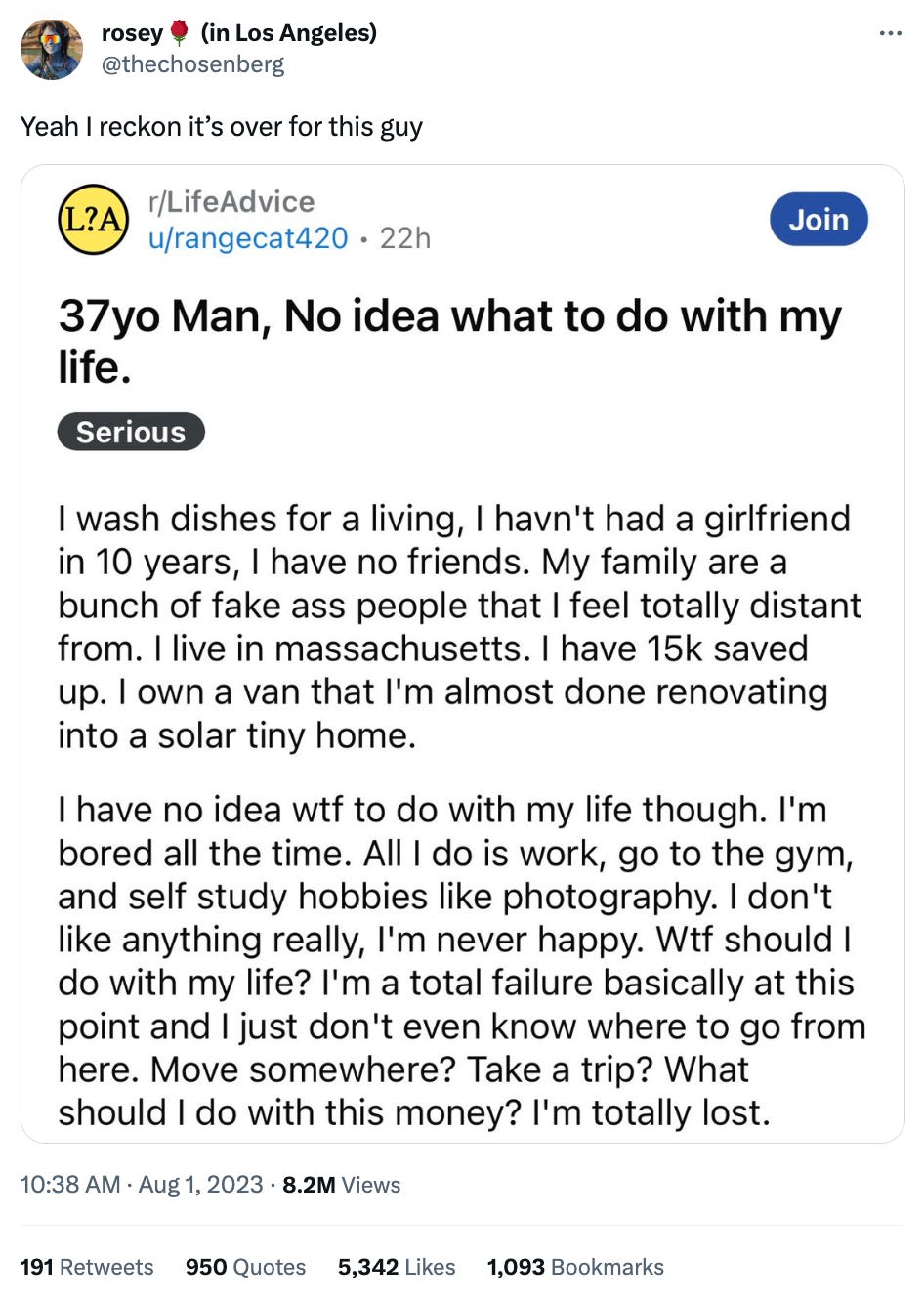

I saw this tweet (or whatever we're calling them now) earlier this week, and I can't stop thinking about it.

I've had several debates with my partner, Will Robbins, about how the next trillion dollar company might be a dating company if they can solve the real problem of loneliness and human connection. These feelings of emptiness, whether in terms of relationships, or fulfillment, there are dozens of takeaways you might have from trying to understand this human's experience.

Venture capitalists would do well to spend less time counting their capital, and more time seeking to understand the human experience, and all the preferences that come from that.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

loved reading it

The last three paragraphs hit hard. Really great article!