This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In 2014, I spent some time at Cambridge and, while sitting in a coffee shop, saw an ad come up on my phone for Wikimania, which was being held just south of me in London. So, I went down, slept on my cousin's couch, and decided to check it out.

Randomly (having never even edited Wikipedia) I attended a multi-day conference of Wikipedia nerds. Unfortunately, the only photographic proof I have of the actual event is like a Lemony Snicket photo where you're not really sure who he is. 🤷♂️

But randomly attending that conference awoke in me a love for the vision of what Wikipedia hoped to be. "The largest collection of human knowledge ever assembled." Many of the criticisms of Wikipedia cite the limitations of the human editors, proper incentive systems, and editing controversies. Ironically, one of the best overviews of most of the controversies that have occurred in editing Wikipedia is the article about Wikipedia controversies ON Wikipedia.

But despite natural human foibles, Wikipedia is a unique and special reflection of humanity's attempt to capture as much knowledge as possible with context and sources cited. The value of that collection has kept it in the top 10 most visited sites globally

Since then, I've been attached to the zeitgeist that is knowledge graphs, wiki editing, and knowledge repositories. My heart yearns for a taste of the spirit of the Library of Alexandria. I've written before about the concept of open-source knowledge and have even built resources like Contrary Research to be an homage to that spirit of the open and collaborative collection of knowledge.

That same love of knowledge gathering that was born from my experience at Wikimania has led me to always sit up and take note when I see headlines about Wikipedia, its parent company, the Wikimedia Foundation, or other relevant topics. That was what happened this week.

"Former CEO of The Wikimedia Says Some Weird Shiz"

Okay, maybe that wasn't exactly the headline, but that was the gist when I saw videos resurfacing of an August 2021 TED Talk by Katherine Maher who, just a few months ago, became the CEO and President of NPR.

I hadn't ever seen the TED Talk (which surprised me). The part of the talk that struck me, as it did everyone who shared the clip, was a discussion at the beginning of the video on "truth." First, Maher introduces what I feel like is a surprising idea:

"The people who write [Wikipedia] articles, they're not focused on the truth. They're focused on something else, which is the best of what we can know right now. Perhaps for our most tricky disagreements, [like religion or politics], seeking the truth and seeking to convince others of the truth might not be the right place to start. In fact, our reverence for the truth might be a distraction that's getting in the way of finding common ground and getting things done."

Now, I'd be surprised if you talked to most Wikipedia editors and they said they were actively not focused on "the truth." Then, in one of the most aggressive uses of the word "but", she dropped this triggering take:

"Now, that is not to say that the truth doesn't exist, nor is it to say that the truth isn’t important. Clearly, the search for the truth has led us to do great things, to learn great things. But... I think if I were to really ask you to think about this, one of the things that we could all acknowledge is that part of the reason we have such glorious chronicles to the human experience and all forms of culture is because we acknowledge there are many different truths."

She goes on to explain that all the various cultural experiences of the billions of people on the planet craft truth from a combination of "facts about the world with our beliefs about the world." The concept bothered me. Subjective truth? Get out of here. But, I was equally bothered by the aggressive and scathing responses on Twitter. So I tried to engage with the ideas across the whole video, and square them with what I believe.

My first belief to address? This conflation of belief as a necessary ingredient in truth does, I think, a disservice to the concepts of both truth AND belief.

Oh Say, What Is Truth?

The idea that truth is relative is very Nietzschean; that "truths" are often fabrications, or "illusions about which one has forgotten that they are illusions." Another way its been put, history is written by the victor. But what these ideas are really describing are stories, not truth.

I've written over and over about storytelling, and the power that it has to "shape" reality. And that's because reality is a lived experience; reality is truth distorted through the lens of experience. You can tell a story long enough and well enough that it becomes reality, or in other words, shape what people believe about the world. And that's true. But the greatest story in the world doesn't change facts.

From Hunter Biden's laptop to the lab leak theory for COVID; the last few years have been riddled with intellectual battles between what the "right truth" is. But determining truth as "desirable" or "undesirable" feels like a real slippery slope.

In July 2023, I helped write a deep dive on the openness of AI and AI safety. In it, I summarized this relevant point:

"In the broader context of disinformation, a new term has emerged. Malinformation, a combination of “malware” and “disinformation.” One definition of the term: “‘malinformation is classified as both intentional and harmful to others’—while being truthful.” In a piece in Discourse Magazine, it discusses the public debate on COVID, vaccines, and the way government, media, and large tech companies like Twitter attempted to control the spread of misinformation:

'“Describing true information as ‘malicious’ already falls into a gray area of regulating public speech. This assumes that the public is gullible and susceptible to harm from words, which necessitates authoritative oversight and filtering of intentionally harmful facts... It does not include intent or harm in the definition of malinformation at all. Rather, ‘malicious’ is truthful information that is simply undesired and “misleading” from the point of view of those who lead the public somewhere. In other words, malinformation is the wrong truth.”'

The idea of “undesired” truth starts to feel eerily similar to the idea of Newspeak and thoughtcrimes explored in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four."

Facts are starting to be colored by preference, but we need to not lose sight of a really important thing: There are facts. There are discernible, measurable facts. But what we, as a society, have gotten worse at is both (1) determining the facts, and (2) accepting the facts.

Now, this is where Maher's TED Talk starts to get a bit of redemption. She talks about how "our truths" come from what we believe, and if we're arguing about what we believe rather than "what can be known," it becomes "deeply divisive and harmful."

Noah Smith makes the point that Maher seems to have to have two ideas about what “truth” is, and failing to engage with those ideas leaves her “thinking at the topic rather than about the topic.” Those two ideas are “subjective truth” and “objective truth.” Subjective truth is becoming more and more important to people. I've written before about a quote from Jordan Klepper:

"We can have debates about what you want. You want this, I want that. Let’s compromise in the middle. That's politics. When your politics becomes who you are, we can't debate that."

And that's true. I think in divisive arguments, like abortion, framing things in terms of what we believe, or who we we are, rather than what can be known, including ancillary consequences of certain policies, create more divisive than effective decision making. Our beliefs have a role, but they are not in defining truth.

Where Do Beliefs Come In?

I've written before about one of my favorite movies; Secondhand Lions. A young boy is living with his two elderly uncles and one of them has been telling stories of the other's exploits in Africa. The boy is desperate to know from the could-be adventurer if the stories are true. So one night he finally confronts his uncle. "I need to know if those stories are true." I've thought about his response a lot over the years:

"Doesn’t matter if they’re true. If you want to believe in something then believe in it. Just because something isn't true that's no reason you can't believe in it. Sometimes, the things that may or may not be true are the things that a man needs to believe in the most. That people are basically good. That honor, courage, and virtue mean everything. That power and money, money and power, mean nothing. That good always triumphs over evil. Doesn’t matter if it’s true or not, you see. A man should believe in those things because those are things worth believing in."

Notice that this is not a conversation about falsifiable facts. Believing that good always triumphs over evil is demonstrably not true. Many, many instances throughout history have proven that evil can dominate, and continue to dominate. Both in individual examples and macro outcomes. But believing in the ability of good to win out in the end is a worthwhile pursuit.

Our beliefs define us as people. And they are important. From Malcolm X to Alexander Hamilton (at least the musical version), the point has been made that a person "who stands for nothing will fall for anything.” Our beliefs are what anchor us.

When Feelings Become Fact

But while our beliefs, and our feelings can be important parts of shaping who we are, they're not meant to displace the reality of the world around us. I've written before about a bit from Ricky Gervais on this idea of facts vs. opinions:

"[Social media] is where this ridiculous notion became stable that it was more important to be popular than right. In this post-truth era people don't care about the argument. They don't look at the argument. They say 'whose saying the argument?' We've always had, 'my opinion is worth as much as your opinion.' But now we've got 'my opinion is worth as much as your facts.' You can have your own opinions but you can't have your own facts."

Now we come to one of the other redeeming qualities of Maher's argument on truth. She introduces this concept of "minimum viable truth," which is "getting it right enough enough of the time to be useful enough to enough people." She believes that we can set aside the beliefs that people have, and get to simpler subsets of truth that can be actionable. We don't have to convince people that climate change is real; we just have to convince people that certain sustainable practices could be more profitable, as one example. And I agree with that!

Two years ago, I wrote about Lowercarbon Capital, and this great quote from Chris Sacca about trying decisively NOT to define what he was doing as impact investing, but to instead appeal to people's greed in proliferating climate solutions:

"I want to sell to people who are acting out of sheer self interest. We have maybe 200 million people who will think about climate when they make a purchase decisions and I need to get 7 billion more. I'm not going to get all these people on the planet to pay a premium out of just consciousness. I just have to offer them a better product. Guilt and shame aren't going to cut it."

So across all of this nuance between truth, facts, beliefs, and identity, I think Maher is actually making a good point; focusing less on what we believe, and more on what can be known, is a good way to sidestep the increasing vitriol with which our beliefs shape our willingness to accept facts.

But unfortunately, Maher's workaround doesn't address the core problem that will continue to plague us.

The Death of Nuance

As I said earlier, the thing we're getting increasingly bad at is (1) determining the facts, and (2) accepting the facts. People's inability to gather information in making a decision is, in large part, the result of an onslaught of what feels like too much information. But instead of getting better at research, we've started looking for shorthands to making decisions. Most of those shorthands come in the form of allowing in-groups to step in as proxies, and make decisions for us. And that reliance on in-groups has made us worse at accepting facts. I've written about this before.

"So often, people trust nuanced tribal group identity and political association without any basis of first principles. I'm not Mormon, or Christian, or Republican, or a Costco member. I am a system of values and beliefs that determine how I act. Group membership should be a lagging indicator of your beliefs, not a leading indicator. When people substitute their own value system with a cookie-cutter platform from their in-group the first thing to die is nuance."

We got bad at research, so we joined more groups. Those groups, supercharged by social media, got really good at telling us what was true and what was false. The more we bought into those in-groups, the worse we got at determining what was true.

So one of the things that Maher's TED Talk gets wrong is that it's okay to cede the argument on "what is truth" in favor of "getting things done." And while that might win the battle, it won't win the war.

Acknowledging that people are getting worse at understanding the world around them is the only way we can start to try and solve the problem. Saying "everyone has their own truth, and its subjective" will only make the problem worse. That idea that "your truth" is reality is what leads to the death of nuance.

Just one example is the radical reaction people across the U.S., particularly young people, have had in regards to the Israeli / Palestine conflict. Watching this documentary from The Free Press is troubling. People feel drawn to this line where, either you have to support everything Israel has ever done, or everything Palestine has done. No nuance. But the nuance forces you to acknowledge that there is both a rise of anti-semitism in the U.S. since the Hamas terrorist attack, and a terrifying offensive from Israel that has killed 10,000 children in Gaza since October 7th alone.

Both things are true. Every issue, everything about which we would do well to better understand, to have more truth. It all has nuance. But our increasing inability both to recognize the relevant facts, and to accept the relevant facts is going to make life that much worse for everybody.

What Does This Have To Do With Venture?

I appreciate you sticking with me through my rant this week. But I promise its relevant to how I think about investing. I keep coming back to this idea that as much as the loss of nuance has poisoned pessimism, and led to things like the pro-Palestine protests leading to a rise in anti-semitism, so too has a loss of nuance poisoned optimism.

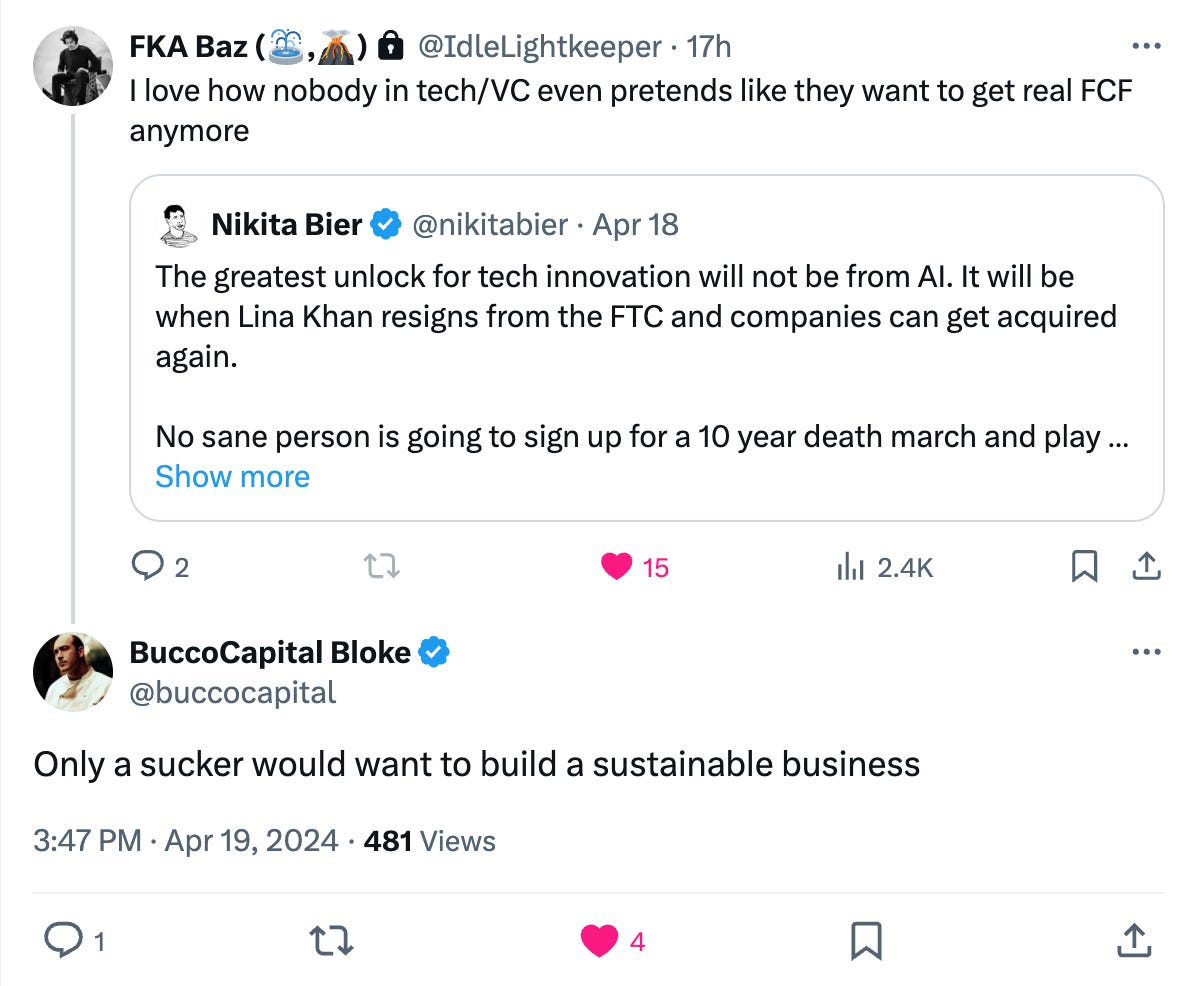

The perverse incentives of venture capital that I've written about over, and over, and over again have made us all more susceptible to hype and hucksters. Our inability to accept nuance; to accept that large, sustainable businesses are incredibly difficult to build, has led us down the path of least resistance. What is hot reigns over what is right.

The only thing that can save us now, across almost every aspect of our lives, is a renaissance of truth seekers.

Not argument builders. Not people who are incredibly capable of supporting an argument, building a bull case, or dreaming the dream.

Not influencers; people who can take their unequivocal opinions and super charge it with either dollars or followers.

But people who are genuinely, spiritually, morally, and financially motivated by finding and displaying the truth, whatever the truth may be. People who want to find the truth so that they can act on it. Not people who write the “truth” because of the decisions they’ve already made.

People who buy the stock because of the story, not the people who tell the story because they bought the stock.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

The last two lines says it all "People who buy the stock because of the story!

Not the people who tell the story because they bought the stock". Keep them coming!