This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I know a lot of people who were obsessed with Game of Thrones. And I know a lot of people who were disappointed by the ending. I never watched the show, but I know that one of the things a lot of fans came to expect was a slew of surprising deaths.

While I can't empathize with the laundry list of medieval surprise deaths, I can relate with the experience having watched The Walking Dead for almost 10 seasons. The show would repeatedly, and gratuitously, kill off characters. Often, characters that you thought they could never do without.

That feeling of week-after-week surprises, many of them gut punches, is how I feel about the news cycle in the world of tech. From the collapse of SVB to the firing of Sam Altman to the return of Sam Altman, it's been one hit after the other. This week was no exception.

ClosedView Venture Partners

For those of you who didn't see the news, OpenView Venture Partners based in Boston abruptly announced that it was laying off the majority of its staff and shutting down new investments. This isn't a first time fund failing to raise a second, or a fringey crowdfunding idea that failed to take shape.

This is a nearly-twenty year old firm with $2.4B of AUM that has invested in companies like Calendly, Datadog, and Expensify. This is a firm that has had some of its investors listed on the Midas List. Of all the venture firms you would expect to shutdown, this was certainly not on my bingo card. So what happened?

As far as all the reporting I've read, this was a case of a partnership that broke down. The firm had previously been led by its founder, Scott Maxwell, and three other general partners — Mackey Craven, Ricky Pelletier, and Blake Bartlett. Apparently quite suddenly, both Pelletier and Craven decided to leave the firm.

Did the firms most recent fund have crappy-looking returns? Sure. It was mostly deployed in 2021. Did the firm have a key man clause that could trigger LP action if certain folks left? Sure. Most firms do. But were the returns uniquely bad? Definitely not. No worse than some jungle cat-themed crossover folks we know. Was the key man clause triggered? No. Maxwell and Bartlett are still with the firm.

So how does a venture fund die? Lucky for me, I've already written about this in detail.

The Death of a Venture Fund

In May 2022, I wrote a piece called "The Death of a Venture Fund" in which I unpacked the ways a VC firm can die, albeit a typically slow death, certainly compared to OpenView's shutdown seemingly within a few days. Some of the biggest drivers? Performance, playing it safe, succession planning, bad timing, or reputation destruction. Almost all of those things take time to kill a venture fund. Outside of outright fraud, its very rare for a venture fund to throw in the towel.

One of the reasons that venture funds are so gosh darn hard to kill is because they have very long lifecycles. A typical venture fund has a lifecycle of 10 years, usually 1-3 years to deploy, and 7-9 years to harvest. As a result, even if you shut down today, you'll still have positions to manage whether you like it or not. For example, OpenView still has ~$1B of deployed capital that they have to manage whether they want to die or not.

There are some firms who revolve their whole business around buying out the portfolios of distress venture funds. Tiger tried to do this with Evercore selling all or some of its positions in an effort to generate near-term liquidity. The biggest obstacle is a main staple of venture capital as an asset class — it's all illiquid. That makes it a much harder asset to move than stocks or bonds.

While this specific firm shutdown may have caught a lot of folks off guard (not the least of which was probably many of the people on the OpenView team), the marked increase in VC shutdowns wasn't a surprise to everyone. Two of the best predictions I saw last year:

The first came from Josh Wolfe at Lux:

And the second came from Frank Rottman at QED:

Diagnosing Death

So what were some of the forces that these investors were seeing? Frank's presentation on the three-body problem in venture was particularly exhaustive. He points to several changing forces that have dramatically transformed the venture landscape:

Massive explosion in the amount of funding

Massive increases in value creation (M&A, IPOs, etc.) (I wrote about this in "What's In A Valuation?")

Increased exposure to playbooks for building startups (I wrote about this in "The Professionalization of Startups")

Increased allocation to private market capital deployment

But as the broader macroeconomic picture has shifted dramatically, each of these forces have been significantly impacted. The amount of funding receded, the value of the outcomes shrank, and the allocation amounts directed to private markets were called into question.

But what didn't change was the knowledge and expertise around how to build companies. Granted, a whole chunk of pages in that playbook became invalidated (I'm looking at you blitzscaling). But the expertise remains. Now the question is what does the market for financial support beams look like that sits adjacent to this playbook?

More recently, Alexander Niehenke wrote a great thread unpacking what is happening in venture.

He makes a similar point to Rotman in how things have now changed:

"The venture business model is "share the pizza pie" which works great when the pie is growing as it has over the past decade. Suddenly that pizza pie is shrinking (smaller funds, longer fundraising cycles, less returns) meaning there are less fees & carry going around."

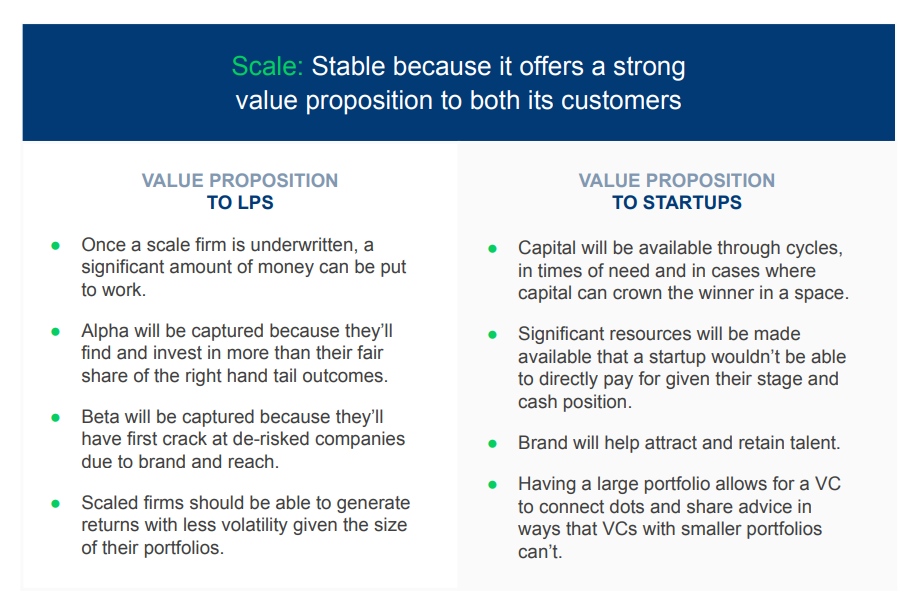

So what do you do? In Rotman's presentation, he talks about a retreat to "distinct points of stability." In his estimation, those points of stability are:

Scale

Non-consensus alpha

Late-stage generalist

Solo capitalist

I would encourage you to go read his whole presentation because it's quite good, and very well thought out. I won't touch on every point, but one point that he makes is one that I've made several times. This idea of the value of scale. Scale brings with it an increased likelihood of seeing deal flow, the ability to balance speed with thoroughness, and an enriched support function that can be subsidized by the fees available at scale.

The Rise of The Capital Agglomerator

I've previously referred to the types of firms that build their entire strategy around scale as "capital agglomerators." I explained it this way:

"These are firms that are truly playing out the vision of becoming the Blackstone of Innovation. The goal is just to raise as much capital as humanly possible. It is unlikely that any of these kinds of firms would do what Founders Fund did a few months ago in cutting its latest venture fund in half. People will ask, "how, in 2023, can you do an investment with a few million of ARR for a $1B valuation?" Because capital agglomerators, by attracting massive LPs who are giving them $250M a pop, are playing a dramatically different game. No LP expects 10x returns on $250M of capital. They're more than happy with 2-3x returns. So those firms are underwriting very different outcomes. They just need those $1B entry prices to become $2-3B companies."

Increased pressure on venture capital as an asset class will continue to further exacerbate concentration. LPs will look for exposure to what they see as the dominant fund managers and likely see a similar form of consolidation to what you've seen in fields like consulting (Big 3), accounting (Big 4), and bulge-bracket banking.

So does that mean the only option is consolidate or die? Not hardly.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Rotman goes into other opportune areas. Josh Wolfe acknowledges that a lot of new firms will form. The way I continue to frame the core takeaway of the rapidly changing forces in venture capital revolve around this idea of requiring every venture fund to answer the question: "why do you deserve to exist?"

In the ZIRP era, the answer could be "because there's money to spend." But not so anymore.

I've explained before this idea of speaking to the "job-to-be-done" that your capital is solving:

"The first piece I wrote about this was "The Productization of Venture Capital." I wrote about how, increasingly, venture firms are going to be forced to clearly articulate their product. Their value proposition. Why should founders hire your money?"

Venture firms will increasingly be required to have an articulate description of the product they offer.

One example? A comfort around capital intensity. I liked how Delian recently put it when describing what obviously plays right into the product offering of Founders Fund:

"I think that if you look at it over the next decade what types of companies are going to be generating the most returns and have the most impact on society, I think people are going to realize that the falsehood of zero marginal cost of software was actually complete fake news, in that if you have zero marginal cost it also means you have zero moat because it means two Stanford grads can go build the same shitty piece of software and go sell it as well.

I think venture capitalists are starting to awaken to the idea that ultimately what you need to be aiming for is the most long tail of outcomes. And if you look at the top 5 companies in the NASDAQ right now--Apple, Nvidia, Tesla. People are starting to realize that in order to build these long tail outcome companies you actually need to build things that tend to be a little bit more capex expensive and so that tends to mean that its something that is easier done when you have venture capitalist effectively as a co-founder. And so I think you'll see some more of it, mostly because I think the most interesting companies are going to be more capex intensive over the next decade."

Comfort around capital intensity is not the only product that can keep a venture fund alive and thriving. There are a myriad of ways to stand out as a firm. But increasingly, the stakes have been raised. And now its not just a question of facing superiority or irrelevance. It's a function of facing qualification for the right to survive, or death.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

A great read Kyle, almost like a pre-mortem of the venture capital fund model. This also relates to your article "Dreaming of Dry Powder" that you wrote in early 2023. Based on thar article, I wrote The Three-Body Problem in Venture Capital:

"Key Takeaways: The incentives of the three key players in venture capital are diverging, $500B in unrealized gains are at risk of being marked down in the coming years, and venture deal terms are starting to look less founder friendly."

"The Three-Body Problem in Venture Capital:

- Founders: Seeking funding urgently before capital dries up.

- VCs: Sitting on 300 billion of dry powder, hesitant to deploy.

- LPs: Prioritizing cash preservation for high-yield, low-risk investments.

While “dry powder” is legally available capital, at the same time, LPs want to preserve cash as interest rates creep up. LPs have an incentive to slow down their capital calls knowing that (a) near risk-free investment returns are increasing, and (b) their investment portfolios are at risk of markdowns."

(Source: https://lawofvc.substack.com/p/26-episode-three-body-problem-venture-capital)

Market Trends and Predictions:

- Investor-Friendly Terms: While investor-friendly terms started to creep up in early 2023, an interesting thing happened in mid to late 2023: Down-rounds shot up to 25%+ of all rounds (at late stage it's even higher). This trend shows up in Carta's data and in Cooley's Q3 2023 Report (29% of all seed financings were down rounds).

- Slower Pace and Lower Valuations: Deal activity has also slowed, with seed-to-A graduation rates dropping significantly (sub 5% for the first 12 months and only up slightly for 2022 cohort). Although legal terms have seen minor adjustments, valuations have generally decreased compared to previous rounds.

- Near Future: These forces point towards two potential outcomes in 2024: significant term adjustments favoring investors or increased startup and fund closures.

That being said, CalPERS just deployed $4.5 billion in the first half of 2023, representing 15% of all capital invested in US VC firms and some of the largest amount of VC capital in its history.

But who received those funds?

> Commitments include $300 million to Lux Capital’s eighth fund, $500 million to Thrive Capital’s eighth fund, $400 million to a new Andreessen Horowitz fund, and $700 million across several General Catalyst funds.

Again, this was for H1 2023, and this doesn't count all of the other fund-of-funds coming into venture.

Very curious to see how all of this capital will shakeout in 2024~!

Interesting read!

Elon Musk called out the fact that "We should have fewer people doing law and fewer people doing finance and more people making stuff". I think that a lot of people are also building software businesses because:

i) The barrier to entry is lower than building a capex intensive business (both from capital and complexity perspective)

ii) Software valuations have been hot and heavy so the promise of a sky-high exit is very alluring to MBA grads

iii) Lots of VCs / PE firms that specialize in SW investing / chasing the next big thing in "mission critical software" (aka demand is high)