This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I have a 6-year old son who likes Legos very much. I recently found myself needing to talk to him, but it happened to come up in the middle of his just digging into a new Lego set. I'd say, "Dax, I need to talk to you for a second." He'd look at me, but within a few seconds of me talking, his eyes would drift back to his Legos, and his hands would quickly follow.

"Dax, I need you to listen to me."

His eyes would snap back to meet mine, but you could feel the pull of his whole body to want to look back at his Legos.

"If you can't listen to me, do I need to take the Legos away?"

Immediately, the stakes were higher, and Dax implemented an effective risk management strategy. He cupped his hands around his eyes, to avoid the possibility of glancing down at his Legos. He then hunkered down to listen to what I had to say, having mitigated the potential risk of losing his Legos.

Kids are pretty smart, and they're not worried about looking silly to get what they really want. Probably worth paying attention.

What's In A Risk?

In the world of investing, there is a lot of talk about risk. In the last few years, when it comes to company building, there hasn't been nearly enough talk about risk. Though, there's always a lot of talk about rewards. Not often enough are the two discussed together. Not just high risk = high reward, but risk as a necessary measurement to understand your rewards.

When it comes to building and investing in startups, it seems that success can largely come from two ridiculously complex buckets: (1) risk management, and (2) luck.

There's a whole other post that could be written about luck. First? Your mental health depends on your accepting that luck is often maniacally random, and unfair. Second? There is a wealth of literature around the concept from Louis Pasteur that "luck favors the prepared mind.”

But in my mind, risk management is separate from those things. Here's the best, most quintessential answer to the question, "what product do founders want to buy from investors?"

In other words? Reduced risk.

Building a company is a massive multivariable calculation of risk-adjusted outcomes. Think about all the checklists you've ever seen where investors tick through the aspects they look for in a potential investment. Marc Andreessen calls this the "onion theory of risk”. Each aspect of a business is another layer:

Founder Risk: Does the startup have the right founding team? A great technologist, plus someone who can run the company? Is the technologist really all that? Is the business person capable of running the company?

Market Risk: Is there a market for the product (using the term product and service interchangeably)? Will anyone want it? Will they pay for it? How much will they pay? How do we know?

Competition Risk: Are there too many other startups already doing this? Is this startup sufficiently differentiated from the other startups, and also differentiated from any large incumbents?

Timing Risk: Is it too early? Is it too late?

Financing Risk: After we invest in this round, how many additional rounds of financing will be required for the company to become profitable, and what will the dollar total be? How certain are we about these estimates? How do we know?

Marketing Risk: Will this startup be able to cut through the noise? How much will marketing cost? Do the economics of customer acquisition — the cost to acquire a customer, and the revenue that customer will generate — work?

Distribution Risk: Does this startup need certain distribution partners to succeed? Will it be able to get them? How? (For example, this is a common problem with mobile startups that need deals with major mobile carriers to succeed.)

Technology Risk: Can the product be built? Does it involve rocket science — or an equivalent, like artificial intelligence or natural language processing? Are there fundamental breakthroughs that need to happen?

Product Risk: Even assuming the product can in theory be built, can this team build it?

Hiring Risk: What positions does the startup need to hire for in order to execute its plan? E.g. a startup planning to build a highscale web service will need a VP of Operations — will the founding team be able to hire a good one?

Founders should constantly be asking questions about all of these risks. And, more importantly, how do we mitigate these risks? In one study that evaluated the power of holding investments for the long-term, and letting the best companies compound, they addressed this idea of risk-mitigation:

"Despite what popular media narrates, entrepreneurs do not seek unnecessary risk; they try to avoid and mitigate risk. Yet students tend to paint a picture of moving from one entrepreneurial venture to another while disregarding risk implications."

The best founders often relentlessly obsess about the risks of what they're building; not as deterrents to stifle their imagination, but as fuel to acknowledge the obstacles they will knock down with their unending optimism. So let's talk about why risk can't be ignored, why it's a necessary part of reward, and learning to live with it.

Survival of the Safest

The last 12 months have been rough. In just a few of the top tech stocks, we've seen $5.2 trillion in market cap get wiped out. Across tech companies, over 150K people were laid off. And the pain is likely far from over, as we still have a number of private startups that seem to be significantly over-valued, and many of them had enough cash that they haven't done massive layoffs or dropped their valuations dramatically, but many of them are still far off from product-market fit, if they can even find it.

The 10+ year bull market hid a multitude of sins, especially in the last few years leading up to 2021. But potentially one of the most significant negative impacts of an insane bull run is the havoc that's been wrought on people's psychology. FOMO and YOLO reached peak, near religious fervor. Being able to sit, quietly, while everyone around you makes money isn’t easy. And very few people managed to avoid the siren call of 2021 speculation.

But the reality is, when you step back to survey the big picture you see that the long game is best summed up by quotes like this:

“Staying in the game is more important than winning a single hand.”

In investing, you'll have ups, and you'll have downs. But the only thing that matters is not getting knocked out of the game. No one doubts Warren Buffett is an exceptional investor; but a huge chunk of his success can be attributed to simply how long he’s been playing the game. 90% of his wealth was created after he turned 65. The movie Wall Street puts it this way: "Remember there are no shortcuts, son. Quick buck artists come and go with every bull market. The steady players make it through the bear."

When you look at some of the best investors, there are countless examples of this mentality. Howard Marks quoted Julian Robertson in his 1997 letter about the mentality of longevity:

"[Julian] Robertson compares today's fund managers to the Phoenician sea captains of thousands of years ago who were paid a percentage of the value of the goods they transported and thus were incentivized to design boats which emphasized speed over safety. This worked as long as the weather was good, but the storms that eventually came consigned the less safe ships to the bottom of the sea. He goes on as follows:

’The last several years have been a great period for the audacious captains with their fleets of fair-weather ships. There has not been a storm for years; perhaps climatic conditions have changed and there will never be another storm. In this scenario the audacious crew with its fleet of swift but flimsy ships is the cargo carrier of choice. [Robertson's ship] will continue to be run as it has in the past; conservatively, making sure its crew and merchandise are safe.’

This metaphor suits Oaktree exactly; we couldn't say it better. Being prepared for stormy weather, even if it could cost us some of the easy money in good times, is certainly the course for us.”

"Even if it costs us some easy money in good times..." If speculation is your game, then by all means ride the waves and run the risk of getting wiped out. But for investors, and founders, who are building things that last—survival is, ultimately, the only game that matters.

A Life Worth Living For

There is a story of a man whose dream was "to board a cruise ship and sail the Mediterranean Sea. He dreamed of walking the streets of Rome, Athens, and Istanbul. He saved every penny until he had enough for his passage."

For fear of the cost of the trip overwhelming his meager savings, he brought a suitcase of crackers and beans. Apart from seeing the cities he'd dreamed of, he stayed in his room. On the ship were countless activities—movies, shows, pools, and feasts. But he limited himself to his simple trip; the risk of over-spending being too much for him.

In many ways, he was seemingly the safest of all the passengers when it came to financial risk. On the last day of the trip, however, he was asked which farewell party he would be attending to conclude the trip. It was then that he learned that every treat of the trip was included in the price of the ticket. Every meal, every amenity, and every party.

He had lived so safely, avoided every risk, that he failed to enjoy the potential he had already earned with the risks he had unknowingly taken when he first bought the ticket. Whether our journey is spiritual, personal, or professional—everything has risk. Every day we walk outside, we run the risk of getting hit by a car. Life is not meant to be lived eliminating risk, but optimizing risk. Managing risk.

So if risk is an unavoidable part of life, there is probably something to be said for learning to live with it, right?

Learning To Risk

Over the last year, I've written a number of times about how everything in investing is learned; whether it's learning to have empathy, or learning to dream the dream. Taking risks is no different; this isn't something you just wake up with the stomach for.

In fact, the longer you wait in your life to take risks, the more difficult it is. There's a very sensitive algorithm in your head that helps you assess risks. The more you have to lose, the more unrealistic the rewards have to be to get you into the game of risk.

People get trapped in this mentality of "once I have X years of experience, or $Y millions saved, then I'll take some risks.” But risk management is a muscle that is developed, not a light switch that is turned off and on.

Risk management can be learned both (1) intellectually, and (2) practically (the latter being basically unavoidable for anyone wanting to effectively learn to manage risk.)

Intellectual Risk Management

One of the best preparations for understanding risk is to understand probability. The most effective risk managers are often actuaries; insurance math junkies who calculate all the likelihoods of a given event in order to price the insurance against that possible event taking place.

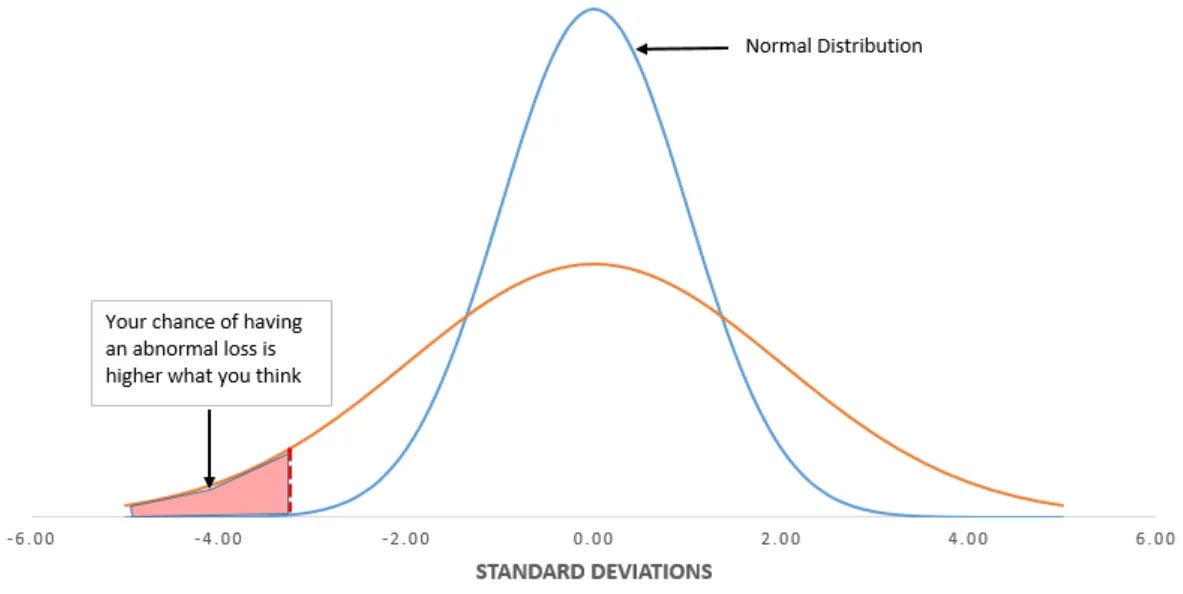

Jamin Ball had a great summary intro to probability a few months ago when he talked about tail risk:

"Tail risk describes the potential of a rare event, as predicted by a probability distribution (mathematically this is generally a move of 3 standard deviations outside the mean). If the graph above represents a distribution curve of outcomes, you can think of tail risk as the red shaded area. In “normal” times tail risk is quite low. This is the blue distribution line. You can barely see the red shaded area under the curve. However, currently the distribution of outcomes is the orange line, which makes the possibility of tail risk much higher. Right now, I think the market is saying 'the potential for a really bad outcome is quite high.'"

Another interesting story to illustrate probability comes from the field of behavioral economics, and thinkers like Richard Thaler, Amos Tversky, and Daniel Kahneman. In one example of the implications of probabilistic thinking, some economists have attempted to value a human life. One illustration of this principle comes from the example of the window washer:

"Assume that a window washer demands $500 in additional compensation to move from washing windows on the first floor to washing windows on the twentieth floor of a skyscraper. Assuming that the additional nineteen-story suspension increases the window washer's probability of death from one in 10,000 to two in 10,000, economists assert that the window washer values her life at $5 million."

When you think about probabilities in this way, you start to form all sorts of risk-adjusted weighted-averages for a whole host of outcomes. I'm willing to spend an extra $100 if I think the satisfaction of flying in the aisle vs. the middle is worth it. If I think my startup has a 20% of dying from competitive risk, then how much is it worth it to me to reduce that risk? How much is it worth it to me to buy my competitor? Or target them directly? Or sacrifice financial health in favor of undercutting them on price?

All well and good. Now, step into the real world.

Practical Risk Management

I had a conversation recently with a founder who is in the earliest days of his journey building a company. He's faced with a pivot. On the one hand, he has a great idea, but no good method of distribution. On the other hand, he has a good (maybe not great) idea, but a really obvious path to distribution. He asked me the question, "which of those is more compelling to you?"

If I were to rephrase his question, he's effectively asking "which of those do you believe in more?" But the reality is, when it comes to the majority of company building, the only thing that really matters is what the founder believes. I've written before about the role storytelling plays in investing, and it's a critical piece. For investors their investments represent their beliefs. For founders, their beliefs are reflected in their companies. Maybe when you're evaluating your "financing risk," then the storytelling of the investor matters as well.

Belief is what drives you forward. Narrative can move mountains. But a line from the movie, A Few Good Men, comes to mind: "It doesn't matter what I believe. It only matters what I can prove." In other words? Everyone has a story, until they get punched in the face by reality.

My answer to that founder's question was: “that's why they call this a game. That's why they talk about placing bets. You have to decide what you believe. How strongly do you believe it? And how much are you willing to bet on it?”

Risk management can only be learned by taking risks. The other side of the coin is religiously conducting post-mortems every time you take a risk, so you can learn from the outcome and recalibrate whether or not you should have taken that risk.

What Does This Mean For Venture?

In my opinion, there are some lines of thinking among investors that can calculate risks incorrectly, but in different ways.

Hedge funds often get it wrong by internalizing short term pain too acutely.

At the end of 1999, Microsoft peaked at a market cap of ~$614B. The height of the dotcom. Over the next year, they would plummet to ~$200B. That's a significant amount of pain in 12 months. That could be enough to leave the mark-to-market folks with such a bad taste in their mouth, they'll leave Microsoft for dead.

From that $600B peak in 1999, Microsoft road the next two decades to the bull market of 2021, and an all-time high of $2.5 trillion in market cap. Even after dropping 25%+ over the last 12 months, Microsoft is still a $1.7 trillion market cap company, and unquestionably one of the most important companies today.

VCs often get it wrong by erroneously believing that the journey is always long.

Venture capitalists love to sing the song of long journeys. "We're in it for the long road, right alongside the founders." That belief can often lead to unchecked optimism, and a limited point of view on the details. But death is typically in the details.

WeWork was an unstoppable behemoth, seeing their valuation rise from $10B to $47B within 4 years. From the first time they filed to go public in August 2019, to when they finally did go public in October 2021, that valuation plummeted to $9B. Today? ~$1B.

In August 2021, Fast was being touted as one of the top private tech companies. Within 8 months, Fast was burning through $10M a month before abruptly shutting down in April 2022.

In September 2022, FTX was proclaimed "a 10 out of 10" with "a total addressable market of every person on the entire planet." By November 2022, the company had declared bankruptcy, and billions in customer funds had disappeared.

In other words? Risk is neither short-term, nor long-term. It is simply measured. You can’t eliminate it, or control it. You can only manage it.

Therefore, what?

Risks come in all shapes and sizes—personal, spiritual, physical, professional. In the words of Andy Rachleff: "Human nature is not comfortable taking risk; so most venture capital firms want high returns, without risk, which doesn't exist." Risk is very similar to failure: "The less time people spend with [it] the less comfortable with it they become."

In everything you do, hone your framework for taking risks. It will likely make all the difference.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

I think you meant Standard Normal. Normal is just the nature of the shape. It doesn't lock/define the area under the tails (kurtosis). Both blue and orange above visually look very much like a Normal curve.

Also, I totally disagree that in the example with the window washer, the washer values their life at 5 million. Very unlikely. If they do, this means that they are completely risk-neutral, i.e. they absolutely do not give a damn about risk. Like a utilitarian robot, they are simply asking for non-risk adjusted compensation due to expected loss of life. This is very different than asking for $1000, because the window washer is risk-averse, or $100 if the window washer is a risk-lover.