This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Note: I was so excited about this piece last week that I postponed publishing it until I had more time. Well, I guess I had more time because I accidentally ran away with it and wrote 10,000 words on the subject. And changed the title. My apologies. This is a long piece. The longest one I’ve ever written on this blog.

But its also a culmination of three big ideas that I’ve been taking seriously for several years. Every company needs a Chief Evangelist. Building cults is a powerful way to build a business. Every story we choose to believe is a vibe we’re creating, and we need to be careful of the implications of what we believe.

Onwards.

"What do you have to believe?"

From my first day as an investor. Evaluating my very first investment. That was the question that started my investing journey. "What do you believe?"

When I started writing consistently, I summed up my intentions for this blog as "a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies." The reality is I've spent an exorbitant amount of time thinking about storytelling and beliefs.

From The Storytelling of Investing to Open-Source Knowledge, Learning To Dream, The Meme Economy, Historical Futurism, The Bubble Brains of Silicon Valley, and on and on. Storytelling has increasingly become front and center in how I think about investing.

When I start thinking about what stories I believe I immediately go to God, religion, family, patriotism. Those are beliefs that reflect who I am. The omnipresence of stories in the human experience means that storytelling is unavoidable when it comes to company building. And every company is a story. For better or worse.

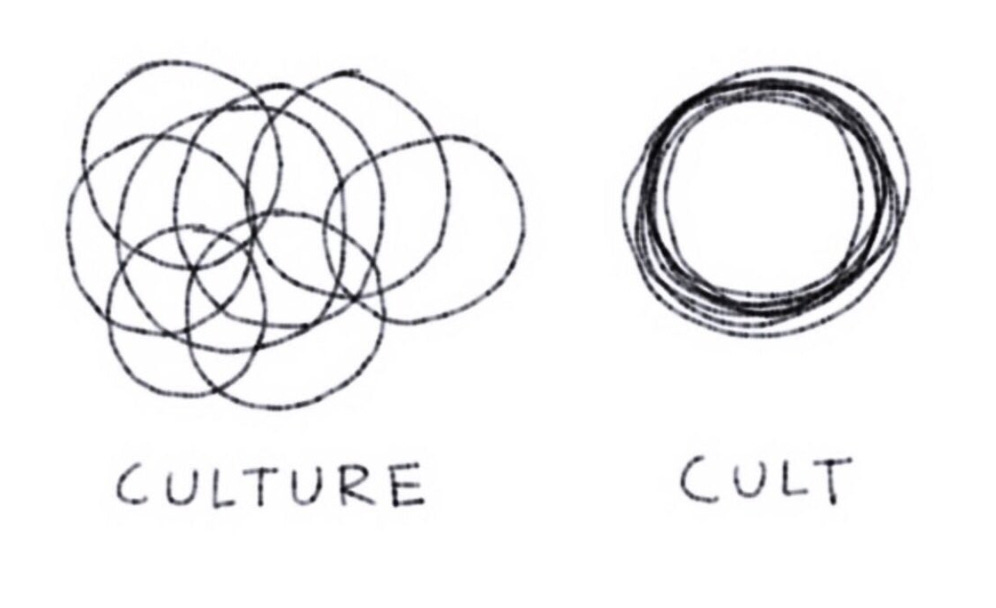

This piece is a collection of reflections I've had over the last several years across a myriad of concepts. Stories shape reality. Storytelling is an art. Every story has its most effective evangelists. And often, the very best stories grow into cults. Whether you like it or not... every company, every movement, every religion, every sports franchise, every pop star, every coffee shop is a cult. I'll unpack why thats the case, why its not such a bad thing, and why it can actually be the most instructive way of building any story.

Storytelling and belief are inextricable because the story is what you believe. I've written before about how "investing should be an act of taking your world view and deploying capital to try and shape reality to that world view." The same can be said of any storytelling. We choose which stories to tell. But the people who choose to believe those stories, and follow them? Those are the result of your world building. And we ought to be thoughtful of what stories we tell, for fear of who might believe them. But tell stories we must. It's the most human thing we can do.

Belief Beyond Reality

Not once, but twice when I was writing about storytelling, I thought of a favorite quote of mine from the movie Secondhand Lions. A young boy is living with his two elderly uncles and one of them has been telling stories of the other's exploits in Africa. The boy is desperate to know from the could-be adventurer if the stories are true. So one night he finally confronts his uncle. "I need to know if those stories are true." His response is instructive about the difference between belief and reality:

"Doesn’t matter if they’re true. If you want to believe in something then believe in it. Just because something isn't true that's no reason you can't believe in it. Sometimes, the things that may or may not be true are the things that a man needs to believe in the most. That people are basically good. That honor, courage, and virtue mean everything. That power and money, money and power, mean nothing. That good always triumphs over evil. Doesn’t matter if it’s true or not, you see. A man should believe in those things because those are things worth believing in."

This isn't a hand-wavey dismissal of the question; "who cares what you believe?" This is about recognizing that people are NOT always good. Evil DOESN'T always triumph over good. But that reality shouldn't stop you from believing that people are basically good. That good will always (eventually) triumph over evil.

Taking the leap of faith to believe in something, despite it not always being true, or not being able to prove its true, can shape your reality. The result of believing in something and then seeing it happen can reform you in a dramatic way. In a 2023 talk by Visakan Veerasamy, he describes this reformation as the result of deviance:

"Once you have succeeded at some kind of deviant shit your ontology is permanently corrupted. You can never again trust anyone else. In 2007, Elon Musk went to Russia to negotiate with some ex-generals to buy missiles to launch a rocket and try and land it again. And all his friends were like, 'Elon, this is a stupid idea.' And he was like, 'I'm gonna do it.' And he did it. I'm not saying these are [necessarily] good people. I'm saying think about what it feels like to have everyone in your life tell you that something can't be done, and then you do it."

That relationship between beliefs and results form what I call...

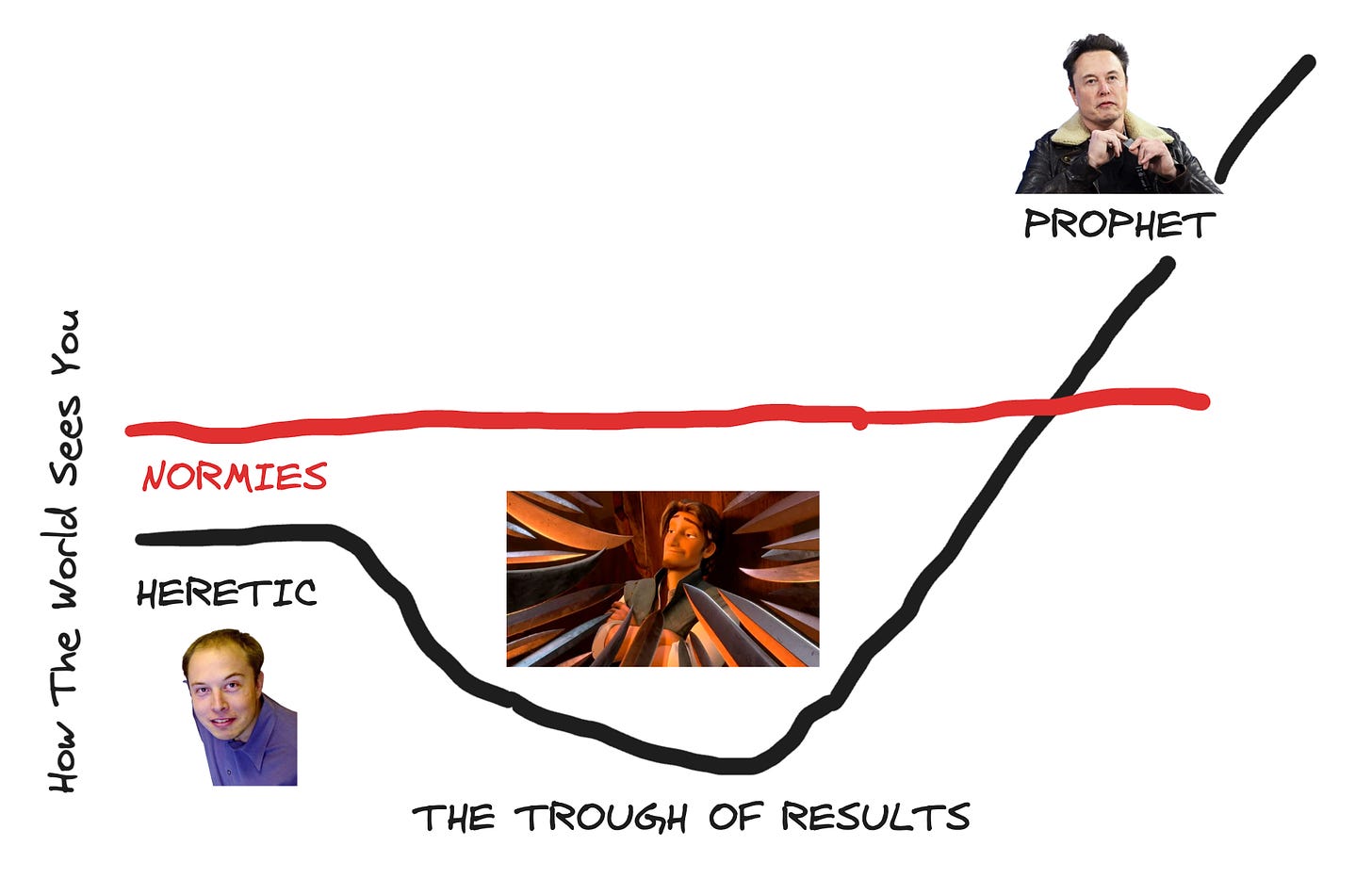

The Trough of Results

Any belief you start out holding that is deviant or contrarian puts you lower in the eyes of the world. You're weirder than the typical normie. Then you set out to act on your heretical beliefs and people think you're dumber and dumber. You blow up rockets (lots of rockets). You get shat on by American heroes. It sucks. But you don't yet have the results to show for it, so you take it.

But over time? The results come in. And over time you prove the status quo wrong. The more right you prove to be, the more you become like a prophet. And for some of the most ambitious projects that belief often does feel prophetic after it comes to fruition. As Frank Rotman puts it, you almost have to have a certain religious conviction to chase these types of ambitions:

"The courage to back companies that only work with massive scale and market dominant positions requires religious conviction. The “all or nothing” path to building dominant companies requires conditional probabilities all falling into place... The path to greatness might look reckless and irrational or it might look organized and thoughtful but the truth is that the only thing that matters is actually getting there. Outcomes pay the bills. Journeys are what stories are written about."

So everyone is choosing what stories they believe. And some people (e.g. founders) decide they want to tell stories of their own. We all choose what stories we're going to believe. And, while we'd all like to think that we're each independently minded and are only pragmatically believing the "true" stories, that isn't always the case.

Storytelling is an art form that invites people along for a ride. And some people are dramatically better at storytelling than others. In some cases storytellers can leverage effective amplifiers of the stories they're trying to tell.

Story Amplifiers

The weakest stories are those which the storyteller feels are entitled to be believed. No story deserves to be believed. Belief is won. The better the story, the more it is believed. These are just a few of the story amplifiers I've observed impacting the quality of a story:

Controversy: In 2020, Rippling put up billboards that specifically threw shade at Gusto. Gusto responded with a cease and desist letter, while Rippling responded to the letter with a poem in Shakespeare-style iambic pentameter. Despite Gusto, at the time, having raised 10x the funding of Rippling, that controversy made it clear that Rippling was most certainly "in the game."

Capital: I've written before about how cash can, definitively, act as a moat if utilized correctly. WeWork, Uber, Snowflake — all benefitted from a meaningful ability to out-fundraise any would-be competitors. You don't even have to actually raise the capital to get it telling a story for you. Remember the rumor mill around Sam Altman's claim that OpenAI would need to raise trillions to build a new chip empire? He chuckled and shook his head later, saying that's just "the sum total of investments that participants in such a venture would need." But you can bet it was a deliberate miscommunication that turned heads for weeks.

Competence: Sometimes you can have a story amplifier that does quite the job of amplifying, even if the story its amplifying turns out to be fairy dust. Think about Quibi. In hindsight, it's the dumbest idea at a junior college startup pitch competition. But at the time? The competence of someone like Jeffrey Katzenberg enabled that story to raise $1.75 BILLION from investors. I've written before about the extreme levels of hubris that resulted in that dumpster fire; but at the time the story was buoyed up by one man’s past success and competence.

Charisma: Some storytellers are like snake charmers; they can lie to your face and you just smile and nod, thinking "their eyes are so wise; they must know something that I don't know." But you're wrong. The idea is, in fact, just as dumb as you think it is. They just have the story amplifier of charisma. Adam Neumann. Chamath. These are pretty atrocious capital allocators who, nevertheless, have managed to raise billions. In large part because they've found a good way to tell a story.

You can see that sometimes these tools amplify good stories and sometimes they amplify bad stories. They're just tools. Every company, every organization, every movement, every individual represents a story. As Muriel Rukeyser said: "The universe is made of stories, not of atoms." There's a whole other conversation to have about what stories are worth telling, and which stories are worth believing in. In the meantime, I'd point you to the piece "Choose Good Quests" by Trae Stephens and Markie Wagner.

But what I'm describing are tools. The playbook upon which so many generational stories are told. And, most often, every story has its bard. Every movement has its leader. Every prophecy has its prophet.

What Is A Chief Evangelist?

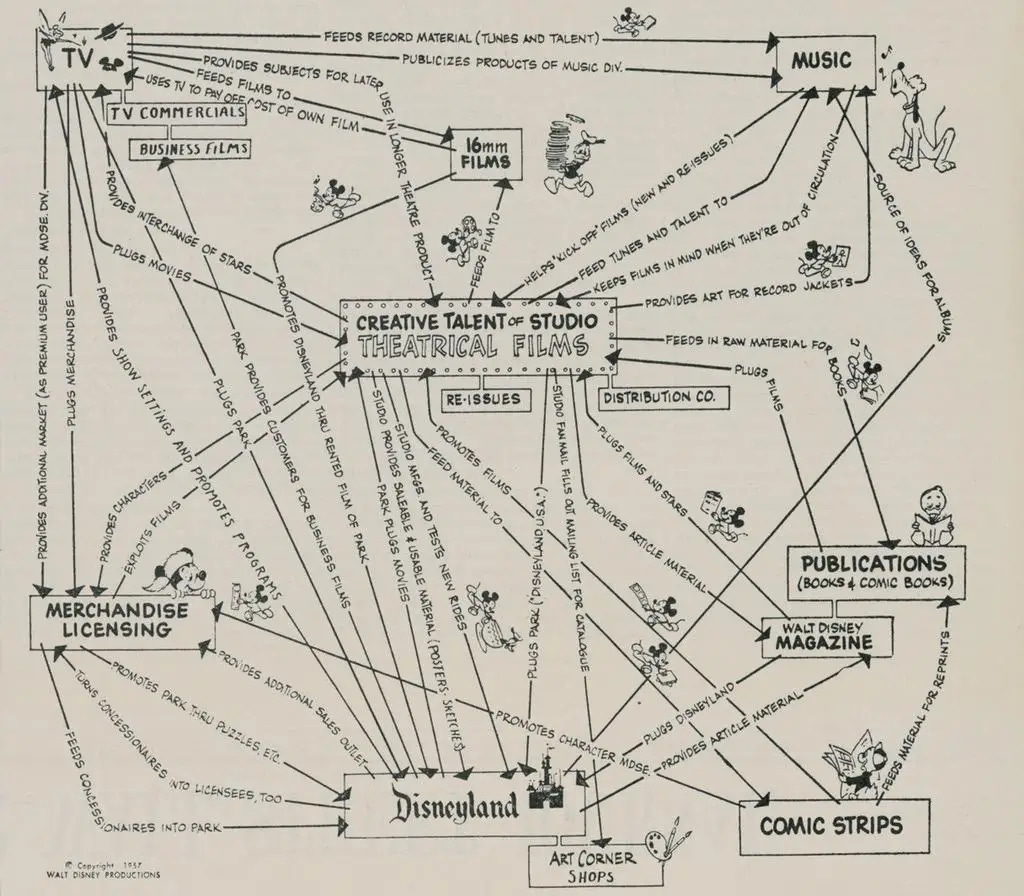

I remember reading "The Art of The Start" in 2016. The book was written by Guy Kawasaki in 2004. Kawasaki was Apple's Chief Evangelist from 1995 to 1997 where he described his role as needing "to protect and preserve the Macintosh cult by doing whatever I had to do." (We'll come back to cults later). He's been the Chief Evangelist for Canva since 2014 (when the company was just two years old).

Reading that book was when I learned that a "Chief Evangelist" was a thing. Since then, I've collected different thoughts and examples of what "evangelism" means for a company. Sometimes its a dedicated role, sometimes its the founder, sometimes its more a function of the company culture itself.

Founder-Level Storytelling

The most prominent example I remember coming across of a true evangelist was Walt Disney. I can't think of anyone who has ever more effectively willed a company into existence, put their face on it, and remained the essence of the business over a long course of time. (He's got Warren Buffett beat by ~7 years; longer if you don’t count the baby Buffett years.)

No disrespect to Walt's animating capabilities; he was clearly a passionate creator. But there's a story of a time when Walt was asked to draw Mickey Mouse at a party and he "simply handed over paper and pen to [Ub] Iwerks and said “Draw it”. Iwerks was, arguably, a more talented animator than Walt Disney.

Similarly, Walt Disney's business history is replete with near bankruptcies. It was his brother, Roy Disney, who managed to keep the company solvent. Roy was, undoubtedly, a better businessman than Walt Disney.

But would the Disney empire exist without Walt Disney? Absolutely not. Iwerks actually tried to build his own animation studio, and was largely unsuccessful. After Walt's death, Roy took over the business and you could argue that the company hasn't been truly revolutionary since.

It was the story. Walt Disney wove a story that, while benefitted by Iwerks talents and Roy's skill, was a literal miracle. Weaving something magical out of thin air.

The same has been said about the early days of Apple where it was Wozniak’s tech, but Steve Jobs’ story. The Apple I might have existed without Jobs. But Apple absolutely wouldn’t have without the vision that Jobs wove into a story to tell the world.

Lulu Cheng Meservey, who is arguably the best tech communications person around today, has written about this founder-quality storytelling when she explained the comms playbook she helped execute at Anduril:

“Comms teams are important and necessary, but not sufficient. Mission-driven startups need founder-led comms. Only a founder can be the chief evangelist for their company. By assuming that responsibility and using that power, you can change narratives, change minds, and change the course of history.”

It is true that the most powerful movements have the founder as the chief evangelist. But that doesn't mean that the cause can't also be carried on by influential evangelists and proxies. Especially those that have the skill and experience to engage in "founder-level storytelling." Trae Stephens, a co-founder of Anduril himself, explained that there is nuance to who can be an evangelist:

"I'm suggesting that you need a founder-level person alongside you in the business. Now, the reason I say founder-like person is that [people] like Jony Ive was not the founder of Apple. But he's a brilliant storyteller, and that was an important part of what made Apple's rebirth work. So I think that you could do this at a very senior level, but it has to to be a a founder-minded person."

I've come across other evangelists that represent a unique perspective that can add to the evangelism of a particular company. Ari Kaplan, for example, is the Head of Evangelism at Databricks. I remember seeing Ari's announcement in December 2022 when he started in his evangelical role. He laid out a crazy impressive resume of the "emerging moments" that he'd been able to help evangelize. He was one of the first people to create an analytics department in major league baseball before Moneyball took off. He was president of a worldwide Oracle user group during the "database revolution.” He worked with Palm Computing when mobile took off. And he'd been riding the AI / ML wave prior to Databricks as a global evangelist at Datarobot.

Another example is Ana Lorena Fabrega, the Chief Evangelist at Synthesis School. Synthesis is a much earlier stage company than Databricks, and Chrisman (the CEO) is absolutely evangelizing the company in a meaningful way. But her experience attending 10 different schools in seven different countries before she was 15 years old set her on a path to forever evangelize better ways to educate kids. From becoming a teacher to joining Synthesis, she has lived the story she tells every day.

So while the storytelling needs to be founder-level, it doesn't come exclusively from the founder. But a key component of the story any founder is telling is the ability to "get away with it."

Getting Away With It

I've written before about how much I hate armchair quarterbacks when it comes to other-worldly ambition and accomplishment. I hate TikTokers like this guy who love to decry people like Elon Musk as idiot frauds. He has issues with who Elon is as a person, so he can't process that he's done anything worthwhile. People like that are desperate to keep people like Elon Musk in the trough of results. But unfortunately for them, the results are in.

Love him or hate him, Elon Musk got done what none of the original co-founders of Tesla would have done. He built SpaceX in a way that the US government couldn’t have ever done. No matter which of his politics you hate, despite whether his Twitter acquisitions thrives or dies, you cannot change that result.

I love this video of Anthony Jeselnik talking about comedy, citing a great quote attributed to Andy Warhol: "Comedy is getting away with it." Jeselnik goes on to expand on the idea as it relates to comedians:

"People think that, as a comic, your job is to get in trouble but they don't want to get yelled at. [They think] it's okay to make people mad, but they don't get any push back. And I think that's wrong. As a comedian, you want to make people laugh. [Andy Warhol said] 'art is getting away with it.' If you put out a special and everyone is pissed you didn't get away with it. You need to make everyone laugh. 'Yeah, he talked about some f*cked up stuff, but we're all happy.' That's art. Otherwise you're just a troll."

Lulu Cheng Meservey explained a similar concept using the example of Google's Gemini chatbot where the results were freakishly "woke" and effectively anti-white. As Lulu explained both the situation, and in particular Sundar's response to it:

“Even in the communication [afterwards] it was all about 'it went wrong because people were offended.' Basically, it didn't work because people got mad. Them optimizing for nobody being offended was the problem in the first place and was why it didn't work."

Connecting Lulu's point to Jeselnik's, it's not about making sure absolutely no one gets offended. If you've watched any of Jeselnik's comedy, you'd be confident he's offended plenty of people. BUT it’s not about making sure no one gets offended. You can offend people, but it’s about getting away with it because (1) it’s true, (2) it’s provocative, (3) you’re just too good to ignore.

In particular, Anduril's CEO, Palmer Luckey, explains that you don't need to care about what everyone in the world thinks. "You need to care about that 1% of the world that is going to be your ride or die." That's what inspires true followers.

Cult-Level Following

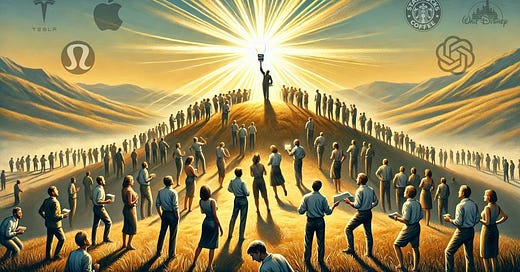

The heretics who successfully navigate their contrarian takes, put up the results, and prove their prophetic propensities tend to achieve exceptional results. In particular, the bigger the ambition the bigger the following. If you have a strong take on how S3 buckets should be optimized and you end up being right? You're a solid engineer. If you believe private companies, instead of governments, should traverse interplanetary space and you're right? The reaction will be slightly more extravagant.

Disney, Jobs, Musk, Altman. People see them as prophets because of their trajectory after coming out of the trough of results. There are absolutely always detractors. Tesla is as attacked by environmentalist as it is oil-maxis. But the power of these cults of success are poignant. And, despite the visceral negative connotations with the word "cult", understanding these cults of success are, in my opinion, one of the most effective ways to understand company storytelling.

Disabusing The Word Cult

When I was 19 years old I served a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. White shirts, black name tags. Whole shebang. I spent all day talking to strangers about Jesus Christ. I remember vividly one day on a sidewalk in Waynesboro, PA I tried to talk to a woman who was walking by. In fact, the memory is so vivid that, without having to go back to my journal, I can still pull up the exact sidewalk where this happened (picture above).

Me: "Hey, good afternoon ma'am."

Her: "Go to hell."

Me: "I'm sorry if you're upset with me."

Her: "Your parents should be arrested for child abuse."

Me: "Why do you think that?"

Her: "For raising you in a cult."

I was usually more persistent, hoping to end on a good note, but that comment literally stopped me in my tracks as the woman stormed away. I'd had people ask if we were a cult before, usually somewhat sheepishly. But to have such a strong reaction, so quickly, it really put a different spin on the word "cult."

After you spend two years talking to thousands of people and the majority of them scream at you or slam a door in your face, you learn not to take much personal. But for some reason, that particular interaction has always stung me when I think back on it. My reaction at the time was to prove we're not a cult. Unfortunately, when you get right down to semantics, that's hard to do. Not just for "Mormons," but for... basically everything.

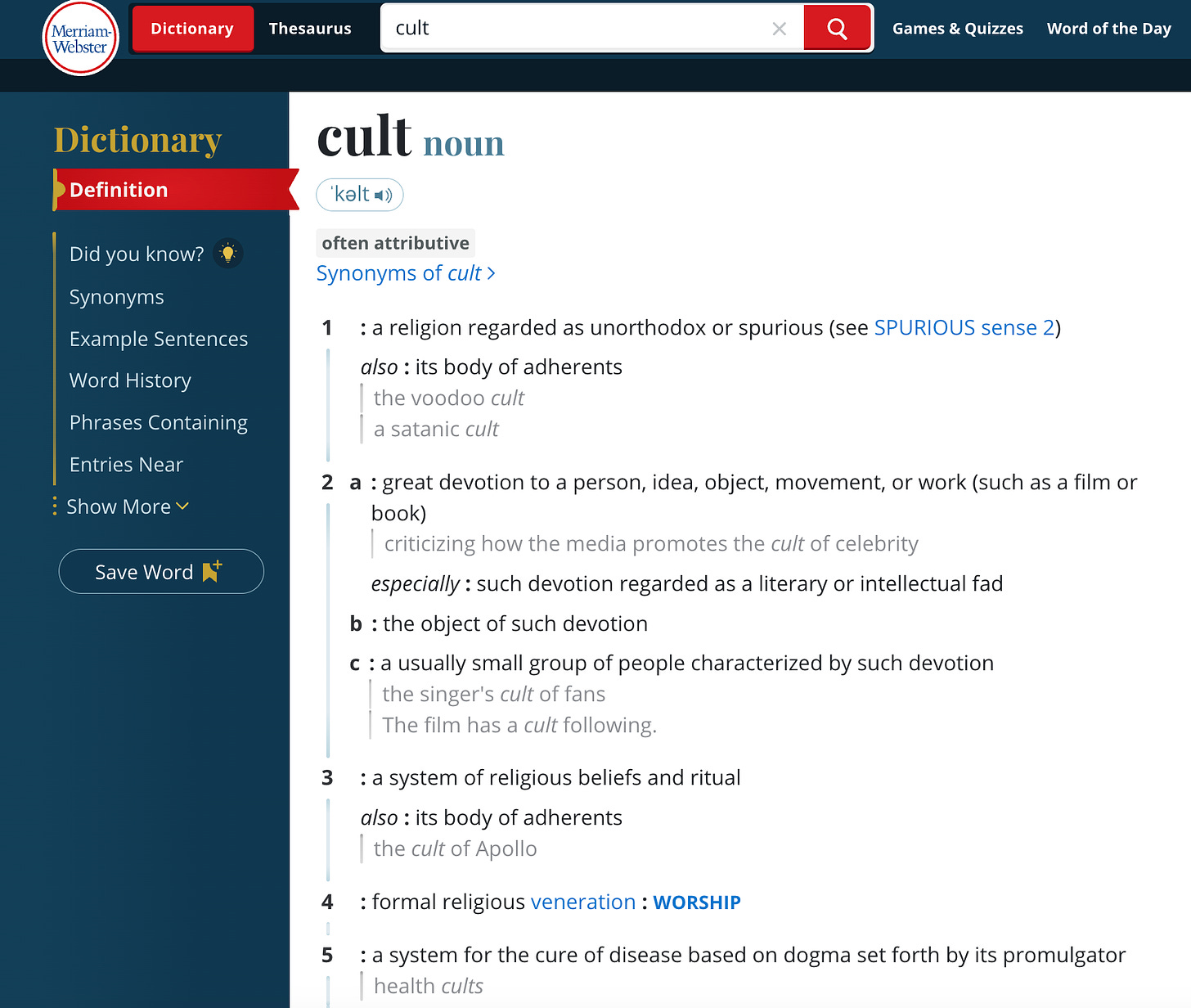

Like any good middle school speech, lets start with what Merriam-Webster's dictionary has to say about it:

Despite my attempt to prove that I'm not in a cult, there's a hiccup. A cult is just a religion that some people think is weird or great devotion to a person or a small group of devotees. There is nothing inherently sinister about the word "cult" other than the fact that the object of devotion is often seen as "unorthodox" or "spurious." Spurious offered some interesting context with its own definition: "Outwardly similar or corresponding to something without having its genuine qualities."

Or, in Visa's words , "deviant."

And, when compared to mainstream Christianity, "Mormons" are, in fact, spurious. Most Christians believe in the Trinity; the doctrine that God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, are all one being. One substance with different essences. I had a Catholic person I taught on my mission explain it this way: "I'm a father, and a husband, and a brother. But I'm one person."

Mormons definitively, defiantly, deviantly DO NOT believe that. We believe "the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost are three separate beings who are one in purpose." So if that, or any other counter-positioned belief of my little group of 17 million devotees feels "spurious" to you then you are well within your rights to consider us a "cult."

People that hate Swifties can call them a cult. Christians that hate Jews can call them a cult. Android users that hate Apple users can call them a cult.

As Conor White-Sullivan, the CEO of Roam Research explained:

"We call the new social systems we like movements, the ones we don’t like cults."

We're going to come back to Conor and the Roam story shortly.

But the takeaway from all of this thought and experience for me is that, in the words of Albus Dumbledore, "Fear of a name increases fear of the thing itself." I'm not afraid to be a part of something called a cult because it says more about the social positioning between the beliefs of the person who calls it that and the beliefs of the person who belongs to it.

There are dangerous cults and there are rewarding cults. There are social cults and there are professional cults. Movies have cult followings. Musicians have cult followings. Cults are all around us. The best stories yield the most fervent cults. We don't yield any benefit by burying our head in the sand. We benefit by recognizing the makings of a movement and why certain things form into a cult and some get left on the dustbin of history.

Every Company a Cult

When I think about company storytelling I often return to two pieces. First, When Creation Goes To Zero by Evan Armstrong. And second, Soft Power in Tech by Mario Gabriele. Read both. They're exceptional.

Evan's point comes down to the fact that companies do three things: (1) create stuff, (2) acquire customers to buy that stuff, and (3) distribute that stuff. And of those three, the internet radically changed number 3 and AI will radically change number 1. The only thing left is effective acquisition. How do you bring people towards your company? Towards your story? How do you evangelize your story in a way that attracts the highest number of the most fervent believers?

Mario's point is that, as the tech industry matures, a company's ability to appeal to a customer not with its product, or brand, but with its narrative will become increasingly important.

"Persuasion may become even more relevant. In the coming decade, we should expect startups of different sizes to develop soft power initiatives alongside their core offerings. Those who do will succeed in building distribution and popularizing the narrative that defines their business. They will create a story that wins. That can have wide-reaching effects, both vaporous and tangible."

OpenAI, as one example, is a company that is uniquely loud. I could be wrong, but I wouldn't be surprised if things like the controversy about making ChatGPT's voice sound like Scarlett Johansson was on purpose. "All press is good press."

Some people think this is a perverse game that they don't want to play. But the reality is that no movement or company or product every impacted the world because nobody heard about them. When Muhammed died there were ~125K Muslims. When Jesus died there were maybe 200 "Christians." Evangelism is what turned those small populations into global phenomenon. The same is true of any product or cause.

Prophecy Pays (Sometimes)

Every story with enough oomph will likely form some kind of cult around it, from Star Wars to Scientology. Some cults persist for a long time, some fall relatively quickly.

Bell Labs was a cult; a pretty good one to boot. But AT&T's monopoly failed and the cult's influence dispersed.

Peloton was / is a cult. It, like most religions, had an NPS of 94. John Foley, Peloton's founder, gave a talk in 2017 where he explained how fitness classes are like modern-day religion. The company had an SVP of Member Experience that described how the company set out to "cultivate emotional loyalty."

Everyone has holes in their heart that they're trying to fill. That can come from community, delight, belonging, satisfaction, efficiency or on and on. The question is whether you can fill one of those holes? I might think more people should dedicate some of their worship to God, but the reality is that people's worship is up for grabs. Some will go to God. Some will go to themselves. But some of it will go to companies. To products. As David Foster Wallace said:

"There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship."

Often, when a cult forms around people’s preferences it can do quite well. In 2020, I remember coming across this tweet that proposed an ETF for cults. Cults like Tesla, Peloton, Apple, etc.

Since December 2020, some of the companies on Bobby's list have seen massive drawdowns, like Peloton (-97%), Zoom (-86%), and Square (-66%). The average return since then across all his names has been ~12%.

So not all cults are created equal. But clearly the size of companies like Coca-Cola, Apple, Netflix, and Tesla demonstrate something special that keeps people coming back. Everyone knows someone who is a Coke fiend (not that kind of coke) or a "Disney adult" or a "Tesla maxi." These cults, in many cases, enable a company to become something that even the people building the company wouldn't have expected. Often the feeling of being in a product cult can be palpable. That was my own experience joining a product cult.

#RoamCult

My experience is probably pretty similar to a lot of people who find themselves getting attracted to a cult. I had what felt like a unique problem that I was dealing with. I had been a note taking fiend for years. From handwritten journals to Evernote to Notion. I'd tried what felt like every possible solution and system. But I always felt like I had a lot of ideas in my notes and no way to connect them.

That's when I stumbled onto Roam Research. Twitter came first, as a lockdown discovery for me, followed by an indoctrination into the Roam community. I fell in love with the way Roam treated each bullet point like an atomic unit of thought. I could connect each idea across my entire network of notes and records, and then see where I'd used that thought in other places. If I had a favorite quote by F. Scott Fitzgerald, for example, I could see all 9 different places I'd referenced it.

From using Roam, I stumbled onto Roam Twitter. I ended up doing Roam Tours where I would do video calls with people and talk about our Roam setups. I've mentioned before, but the first blog I wrote on this Substack was about how I use Roam in my investing research. To simplify the discovery experience for Roam users on Twitter we all started using the #RoamCult hashtag. There were Apostles of Roam. You could buy a lifetime membership to the software by paying for the "Believer Plan."

One Roam user described the experience well:

"Being in a software community, especially so early on in the program’s lifetime, is a weird experience. The app is being developed in front of your eyes and you can even influence its direction. You can complain to its creators and they may sometimes answer to you. You get also new virtual friends/influencers, you can join a Slack channel and you start to get direct messages on Twitter with questions on how to solve one or another problem in the program — you are “INSIDE” the community."

That's how a lot of us felt joining the Roam Cult.

What's In a Cult?

Roam mania really peaked in the early days of COVID. In early 2021, Conor, the CEO of Roam, posted a thread about why he wanted to move away from the #RoamCult moniker because there are real cults out there that are scary and, in fact, the opposite of what he wanted the Roam community to be. His thread is quite good. But I see it now, in hindsight, less of an indictment of building a cult and more an overview of how to avoid building a bad cult. So I've added some little adjustments to reflect what I think is my takeaway:

"[Bad] cults are real and all around us. They seek to control and manipulate members, break bonds, isolate people from friends and family, destroy the individuals faith in themselves, and to be an unchallengeable fountain of “truth” that their adherents never question.

One of most beautiful things about our universe is that there are endless new truths to discover. If you approach problems with humility, and with genuine curiosity rather than a desire to be “right” or for a cheap way to feel superior to others, she will share secrets with you.

New ideas will always be met with resistance, often they challenge the status quo, and people who have power and prestige in the current paradigm may perceive the secret you found as a threat, or as an illegitimate grab for status. Rejection and ridicule are common reactions.

I have a huge amount of respect for anyone who is honestly seeking to help the universe unlock its secrets. it isn’t easy to find Good Explanations, but it’s hard to underestimate their power for improving our condition. And I’ve seen plenty of great [cults] unfairly called [bad] cults.

We call the new social systems we like movements, the ones we don’t like cults."

Conor's sentiment represents a powerful overview of how effective good cults can be. People who are meaningfully committed to the pursuit of new ideas, challenging the status quo, and seeking to unlock the secrets of the universe. At its best, that's what you would hope a cult is. That's what you hope people are annoyingly committed to.

Unfortunately, the Roam Cult failed. The excitement about Roam sparked a movement around note taking that reinvigorated people's excitement around personal knowledge management. Roam even made Notion, a $2 billion company at the time, come out and dance. In June 2021, Notion launched "synced blocks" as a way to address user demand for referenceable atomic units in Notion.

But the energy of the #RoamCult in 2020 is lost.

Why? There is a better case study to be written on why Roam Research fizzled out. This isn't that. And I'll caveat with saying I am still, to this day, to this moment, an hourly active user of Roam. My whole life is in it. But it's accurate to say that the product I'm using today is not fundamentally different than the product I started using four years ago.

Reflecting on my experience with the Roam Cult allows me to reflect on what a cult can and should be. But Roam's failure comes from losing out on what I think are two critical steps to building a product cult: (1) build a product that represents an aspect of people's life philosophy, AND (2) ship features that continue to delight.

Roam truly did do the former. But they did not do the latter. I'm a power user of Roam. I'm as loyal a loyalist as a product could have. But now, four years into using the product, I still have to be okay with using Apple Notes on my phone and then moving it to Roam because my Roam graph is too big to load on Roam's mobile app.

But I still dare to dream about what COULD have been. If Roam had continued to ship. If they had built the team they needed. If the #RoamCult energy of 2020 had continued to burn brightly. If many of Roam's most fervent users and community members hadn't been turned off by their experience. What could have been? I still hold out hope for the global knowledge graph. And I still hold out hope for Roam Research. I'm not switching off it anytime soon.

But instead of writing a post-mortem on Roam Research, I'm instead sitting back and reflecting on the experience I had in that cult. What was good? What felt like the ingredients to capture that lightning in a bottle, even if it was for ever so brief a time? Because the people and organizations who can build that cult-like energy are the people who, in Mario's words, can "create a story that wins."

Building a Cult

Unfortunately, given the negative connotations around building cults, the only guides that exist are sarcastic unnerving videos like this on how to build bad cults. But instead you can look to the people who have laid out details around how to build movements (e.g. the new social systems we like) such as this TED Talk from Derek Sivers called "How To Start a Movement". Or you can turn to the companies that have built cults themselves. Companies like Apple, Microsoft, or even Bitcoin! And learn from them.

Courage To Stand Out

In Derek Sivers' talk he uses the example of a famous video from 2010 of a guy dancing alone at a festival. Over time people start to join him until an entire crowd is dancing on the hill. Derek's first point?

"A leader needs the guts to stand out and be ridiculed."

People often talk about the need to be "contrarian and right." Being right is how you fulfill the requirements of the trough of results. If you're not right, you just stay a heretic. And a wrong heretic at that. But being contrarian in the first place is what draws the attention. The heresy. The deviance.

Apple knew that willingness to stand out was exactly the characteristic of an Apple cultist. Willing to do things differently. That's why their most famous early ad was called "Think Different."

Start With Why

You can believe anything you want. No one can stop you from that. But to go from one person's belief to appealing to anyone else it begins with a "why."

When I was a missionary I happened to stumble on a document entitled "Why I Believe." It struck me, at first, as something you only write if you've started to doubt your belief. But as I read it, I realized it was a more fundamental collection of first principles. This was an older gentleman putting down why he felt inclined to his particular beliefs.

Simon Kinek has a great video that's 10+ years old now and I still think about it. The point of the video is to "start with why." The same idea as "Why I Believe" — a core belief or purpose, which drives actions and distinguishes an organization / movement / team from others.

Every cult revolves around a why. A "job-to-be-done" so to speak. Belonging, satisfaction, education, meaning. Whether the cult is good or bad depends on how it satisfies that need. Through honesty? Or manipulation? Articulating the why, the why should I care. For the investor, the "why should I believe?" Those are the things that attract followers.

The Importance of The First Follower

Once a gutsy leader is willing to be contrarian in pursuit of a vision, and can articulate a "why" for any would-be followers, you can start to attract a following. Back to Derek Sivers' talk, he points this out:

"The first follower is actually an underestimated form of leadership in itself. It takes guts to stand out like that. The first follower is what transforms a lone nut into a leader."

There's a great story I read in a deep dive on Microsoft written by Mostly Borrowed Ideas (MBI). In it, he tells the story from a book about the founding of Microsoft and its "prophet" co-founders, Bill Gates and Paul Allen. This quote is a mix of MBI's deep dive and the book:

"Although Allen was almost three years older than Gates, their mutual passion for computers led to a close friendship; nonetheless, they were very different personalities, as alluded by Allen’s recollection of how his mother used to describe Gates: “My mother had a term for adrenaline junkies, people who would court risk for the thrill of it. Bill Gates was an edge walker, where I was wary of danger, Bill seemed to enjoy it.”

By the time Allen decided to leave his “dead-end job” at Honeywell to start a company with “the edge walker” named Gates, Gates and Allen were just 19-year and 22-year old respectively. While the popular perception of the teen Gates mostly focuses on being a computer nerd prodigy, it was his sales skills, in addition to technical prowess, that became important backbone of Microsoft’s early days. From the book “Hard Drive”:

'Gates sustained Microsoft through tireless salesmanship. For several years, he alone made the cold calls and haggled, cajoled, browbeat, and harangued the hardware makers of the emerging personal computer industry, convincing them to buy Microsoft's services and products. He was the best kind of salesman there is. He knew the product, and he believed in it. He approached every client with the zealotry of a true believer, from the day he first articulated the Microsoft mantra: "A computer on every desktop, and Microsoft software in every computer.'"

There are leaders and there are followers. There are edge walkers and there are... followers. I couldn't think of a clever word for followers that would go with edge walkers. 🤷 This dynamic reminded me of a West Wing clip I've written about several times before:

"The President's deputy chief of staff is frustrated because he's failed to accomplish something. The president says, ‘the difference between you and me is I want to be 'the guy.' You want to be the guy that 'the guy' counts on.’"

The importance of that first follower can't be overstated. But I also want to call attention to how Bill Gates was described: "the best kind of salesman there is. He knew the product and he believed in it. He approached every client with the zealotry of a true believer." I can't think of a better description of a Chief Evangelist than that.

Build Universal Exclusivity

There is something unique about a successful (and GOOD) cult. It has a sense of exclusivity but one that is universally accessible. In the words of scripture, "many are called, few are chosen." A good cult is open to everyone, but it asks something of its members. A way of life, a way of thinking, a way of operating, a way of being. That sacrifice is what maintains exclusivity. Anyone COULD benefit from the cult, but only the select few will.

There's a great story from when Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone:

"Early on Jobs even shows a reporter the iPhone's touch-screen keyboard. The reporter hesitates: 'It doesn’t work.' Jobs stops. The reporter kept making typos and said the keys were too small for his thumbs. Jobs smiles and replies: 'Your thumbs will learn.'"

At first, new cults come with a bit of an operating manual to unlock the benefit. But they're not meant to be exclusive. They're meant to be inviting. The goal is to unlock something special. Functionally, the iPhone was a dramatic improvement from the Blackberry. But it took some learning. But once your "thumbs learn," you're in for a treat. And if the experience is good enough and the advantages of the cult are overpowering then you have a shot at ubiquity.

And that's the goal. Exclusive enough to be inviting, but universal enough to be ubiquitous. Seek ubiquity. Band-aids is a movement, not a product. Kleenex is a movement, not a product. Googling something... I think is safe in the echelon of movement vs. just a product. We may always refer to searching for something as googling cause we're never going to say "I ChatGPT'd it" or "I perplexity'd it." I googled it.

Creating Language

"Googling." "On-chain." "Baptism." That "operating manual" is a key component of the cult. I always think about the 1994 episode of The Today Show where the hosts are debating what "@" means, and end up asking "what is the internet, anyways?"

Often that language, that operating manual, it becomes the stuff of legend. For example, there's one word that has come to mean so much to so many people that thousands of boys and girls get aspirationally giddy just hearing the word. Here's from the book "Walt Disney and The Promise of Progress City":

“Engineers tend to be concerned with physical things in and of themselves. Architects are more directly concerned with the human interface with physical things. An architect knows something about everything. An engineer knows everything about one thing.” Walt well understood this tension between planners, architects, and engineers and with great pride coined the name for his team of designers that represents a blending of all of the disciplines."

The word? Imagineer.

The language is not always inviting. #RoamCult for example was a rallying cry; Twitter was the means of communication and the Roam tag brought everyone together. But I remember plenty of people being uncomfortable with the moniker (including the CEO later on). It felt exclusive. Anduril's Chief Strategy Officer wrote a book laying out the company's strategy; the book is called Kill Chain. A lot of people aren't comfortable with the language, let alone the idea, of killing.

Who the language works for goes back to Palmer Luckey's point in getting away with it. The language can offend lots of people other than a particular group:

"You need to care about that 1% of the world that is going to be your ride or die."

Hiring Critics

There's a great story that the Founders Podcast talks about both in relation to Akio Morita, the founder of Sony, and Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid. First, from Morita, the concept of hiring critics:

"Norio Ohga, who had been a vocal art student at the Tokyo University of Arts when he first saw our first audio tape recorder back in 1950." So he says, "I had had my eyes on him for all those years because of his bold criticism of our first machine. He was a great champion of the tape recorder, but he was severe with us because he didn't think our early machines were good enough."

This paid critic he hires eventually becomes the President of Sony. "So he was severe with us because he didn't think our early machine was good enough." So he's got somebody else, he's got an external person holding himself to even higher level of quality than he did. So he says, "It had too much wow and flutter, he said. He was right of course. Our first machine was rather primitive. We invited him to be a paid critic even when he was still in school."

Edwin Land took a similar approach when he was building cameras:

"For a retainer of $100 a month, Land got Ansel Adams," so Ansel Adams, maybe the most famous photographer in this time period. He says, "He got Ansel Adams' formidable knowledge on tap." So what does that mean? "Adams stayed on the payroll for the rest of his professional life, though as he hasten to point out in 1972, the stipend had risen to considerably more than $100 a month. "Whenever Polaroid introduced a new product line, Adams trooped off to the mountains or the desert to try it out. Back came reports, packed with detail, containing rows of photos at varying exposures or apertures. Eventually Adams filed more than 3,000 of these reports." You now have one of the best photographers on retainer and all he's doing is testing your product, finding where it's weak, where it can be improved and then sending you back reports. That is worth way more than whatever you're paying him every month.

From Walt Disney to Steve Jobs there is a frequent obsession with quality. And with that obsession comes the need for criticism. What is unique about this need for criticism is that its rare for a cult. Bad cults thrive on secrecy, on control. Good cults? Thrive on truth. No matter how harsh, no matter the source.

Pursuit of Truth

Here's a quote about truth that, while religious, is an aspiration for every organization:

“We believe in all truth, no matter to what subject it may refer. No sect or religious denomination [or, I may say, no searcher of truth] in the world possesses a single principle of truth that we do not accept or that we will reject. We are willing to receive all truth, from whatever source it may come; for truth will stand, truth will endure.”

Every organization should operate in pursuit of truth. The guiding question shouldn't be "what can we convince people of" or "to whom can we pass this bag that we don't actually believe in?" The guiding question should be "what is true?

Unfortunately, most cults, both bad and good, are so pervasive and (for many) so tentative that they quickly become anti-heretical despite their history of being built by heretics. If you're afraid that your cult is wrong then you're much more inclined to argue about it being true. Finding cults that allow you to seek truth, even when its uncomfortable, are much more likely to establish more truth, rather than limiting truth.

Bad cults often force uniformity through fear and social pressure. The goal should be to seek uniformity, not because its forced, or because you’re afraid, but because its true. The goal of any good cult should be to find the unifying truths. The secrets of the universe.

Avoid Elitism

The danger of bad cults can also be a feeling of superiority within the group. Elitism rears its ugly heads. Religious communities often engender a toxic "keeping up with the Jones's" vibe. The prosperity gospel makes you think your comparative wealth is reflective of your comparative piety. One former Roam Cult member described a key reason for people departing the Roam community as "a perceived trend of elitist interactions in the Roam community. For some, there is no room for any other than Roam."

Religions struggle with the same thing. I call it the "One True Church Syndrome." The idea that you are right in exclusion of all others creates an unhealthy elitism. The goal of a good cult should be to invite all truth, no matter the source. As Gordon B. Hinckley said, “Bring with you all that you have of good and truth which you have received from whatever source, and come and let us see if we may add to it."

Returning to Derek Sivers' talk, he points out the idea that in a good movement, or in my words a good cult, "the leader embraces [the followers] as an equal so now its not about the leader; it's about them plural."

Emphasize Education

One of the most powerful aspects of building a cult, particularly as it relates to fast-growing communities and products that require adoption, is the presence of built-in onboarding. Nikhil Trivedi, a Roam user and investor, described the power of the education inherent in that potential for community onboarding:

"If the expected economic return on an acquired customer is low, any acquisition path that requires education of that consumer to the virtues of the product will inevitably lead to failure unless a macro tailwind or zeitgeist eventually eliminates the educational cost."

In other words, if you only get a certain amount of incremental value from a user then its not economically viable to pay for that users’ education. Especially if the education is costly or high friction. But any product can benefit from a macro tailwind or a zeitgeist to "outsource" the educational cost.

One Roam user made this point about how powerful the #RoamCult was for onboarding and education:

"I was thinking about how Roam Research doesn't ever need to pay for community management if it doesn't want to. RoamCult forms, storms, norms, and performs ad hoc. Unsure how many tech companies can confidently say that. Community management itself seems unwieldy to value as an occupation. I notice that on the one extreme it's done selflessly for free by active members of the community, sort of like Twitch or Discord mods. If culture eats strategy for breakfast, I think it eats system design for lunch and finishes up with community management for dinner."

Now, back to Nikhil's point, if the zeitgeist fails then the cost of education becomes too high. That’s what happened to Roam. Early on, users like Nat Eliason built full onboarding courses independent of the company. But over time if the zeitgeist dies, then that happens less and less. Addressing this problem is the whole purpose of user communities and "developer relations" as a category. Unfortunately the professionalization of those categories has made them stiff and PR-esque, which has moved the vibe away from "founder-level evangelism."

Therefore, What?

Some people won't make it nearly this far in this blog post just because I accidentally made it so freaking long (my bad). Some people won't make it because they're turned off but the "cult" of it all (understandable). But if you've made it this far I wanted to make three final points. First, we need more cults in this world. Second, each one of us represents a cult of our own personality that we have to manage. And third, we all have to be careful what we worship.

We Need More Cults

In 2020, Wolf Tivy, the founder and former editor of Palladium Magazine, wrote a thread about cults that I found instructive.

Some key takeaways for me that sum up this first point:

“Many nonprofits sit in the space that should be occupied by cults. The difference is in the narrative of managerial professionalism, detachment from the thing. A cult doesn't have a pitch deck and impact-focused patrons, it has an initiation, and wealthy cult members.

Some businesses are actually cults. SpaceX is a rocket cult for example. What about Amazon? Is Amazon an infrastructure cult or any other kind of cult?

I mean cult in the classical sense: an organized division within society's overall religion that has serious devotees to it's specific teleology."

If done correctly, cults can be the powerful mechanisms by which powerful stories are harnessed to powerful effect. The better we are at understanding what makes a cult successful, the more capable we are of harnessing that power for good, rather than for evil.

A Cult of YOUR Personality

Every person is a story. People use different tools and mechanisms to communicate their vibes. Social media, writing, videos, storming national capitols. Whatever floats their vibe boat. Some are effective, some are not. I've written before about this quote from Tim Urban:

"A few brave people speaking out shatters the delusion and makes others realize they're not alone. When more people start saying what they think, it becomes less scary for others to follow in their footsteps."

The benefit of a cult is that it gives a channel for beliefs. But, as I've written about many times, actions should be lagging indicators of beliefs, not leading indicators. We shouldn't believe something because we joined a cult. We should join a cult because we believe something.

As we craft those beliefs, we build influence. I've written before about an exceptional quote from Morgan Housel where he talks about Howard Marks and Warren Buffett's approaches to building their vibes up:

"I think Warren Buffett and Howard Marks were really the forerunners for all of this. They were not just giving their investors more information, but they were using their ability to communicate as a bridge towards trust. And that’s really what it was.

So many investors will say 'Oh I went back and read Warren Buffet’s letters to shareholders and they’re so enlightening.' I think, for the most part, there’s actually not that much technical information in there that most people didn’t already know. If you have a finance background, you understand a free cash flow and value and margin of safety. You get all of that. But Buffett’s letters instilled the sense of like subconscious trust. The way Buffett describes things gives you this view of: 'Hey, you’re not trying to screw me.' Buffett and Marks more or less had permanent capital because their investors trusted them. And because of that trust, all these other hedge fund managers and private equity managers that during a bear market, their investors would have said, “I don’t trust you anymore. I’m out of here. Give me my money back.”

But investors didn’t do that for Buffett or Marks, and that’s a massive competitive advantage right there. So put all that together. Buffett and Marks used content to instill trust, trust gave them permanent capital, and permanent capital gave them a massive financial advantage over other investors.

Each of us attempts to communicate our vibes and, in so doing, we craft the cult of personality. Of our own personality. And we need to be deliberate how we shape that cult. That image. That reputation. Because, as Warren Buffett says, “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you'll do things differently.”

Be Careful What You Worship

Finally, I'll end with this. Earlier, I quoted David Foster Wallace talking about worshiping. But the full quote is a critical takeaway worth completing:

"There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And an outstanding reason for choosing some sort of God or spiritual-type thing to worship — be it J.C. or Allah, be it Yahweh or the Wiccan mother-goddess or the Four Noble Truths or some infrangible set of ethical principles — is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things — if they are where you tap real meaning in life — then you will never have enough. Never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your own body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly, and when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally plant you."

Your time, talents, attention, energy, passion — these are the finite gifts you've been given in the brief time you have on the earth. You should never disrespect that gift by allocating yourself to cults, causes, or creeds that are not worthy of you.

You decide what you worship. You decide what cults you'll join. You decide what you'll believe. You decide what cults you'll build. You decide what stories you'll tell.

So make them good ones.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

This is a fantastic piece. I love the framing on the need for additional cults - definitely worth the long read.

It might have been a long read but it was worth it!

Great post. So much to chew on. In my head I kept coming back to the quote from the Iron Lady Film

"Watch your thoughts, for they become words. Watch your words, for they become actions. Watch your actions, for they become habits. Watch your habits, for they become your character. And watch your character, for it becomes your destiny…”

Watch your stories with good reason