This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Andrew Stanton, one of the filmmakers at Pixar known for directing Finding Nemo, WALL-E, and more, gave a TED Talk in 2012 where he talked about storytelling. At the beginning he tells a story about how an old Scottish man came by his colorful nickname. Now, I won't repeat the story, cause my Mom reads this blog. But give it a listen. And just think about what's in a name, and the story behind it.

That's how I felt as I was reading the Wikipedia entry for the term "Ponzi scheme." I always forget that the term comes from a specific person; Charles Ponzi in 1920. His scheme of paying back his first wave of investors with the cash from his second wave of investors earned him $220M in today's dollars. It wasn't the first known Ponzi scheme (that happened in 1869) and it wasn't the biggest (that probably goes to Bernie Maddoff, who caused the loss of $20B in cash and $65B on paper.) But Charles Ponzi's name would forever be attached to the scheme.

So what's got me thinking about Ponzi schemes? Yet another attempt to understand incentives in the world of venture capital. This time its using Instacart's cap table to unpack the value chain of capital.

What Is The Venture Capital Value Chain?

Last week, Instacart went public at a $9.9B valuation, down from an all-time-high in early 2021 of $39B. It was one of the first big IPOs since the market corrected, and there was a lot of interesting commentary. But my favorite was this video from Aswath Damodaran, an economics professor at NYU.

In that video, he shared this break down of the equity return from each of Instacart's funding rounds:

The takeaway was that every investment round from the Series C in 2015 to the $39B Series I in 2021 has failed to beat the S&P 500 in terms of returns. And every round since 2018 is basically flat or negative.

The first reaction was, "well no one should have invested after that 2014 Series B." Most investors are using benchmarks like beating the S&P 500, so in retrospect no one would want to make an investment anywhere it wouldn't beat the market, right?

But here's the dependency. All of Instacart's funding up to and including the Series B? $55.7M

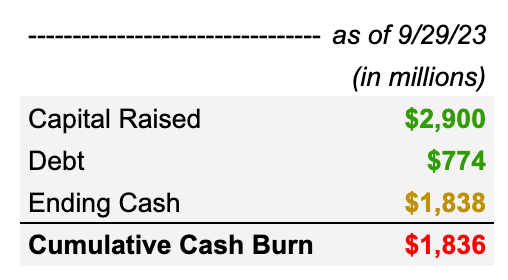

Now, this is just a rough estimate because we don't have visibility into all the cash inflows and outflows over the business's life. But as of yesterday, the company had raised a total of $2.9B in total funding, they had existing debt of $774M, and an ending cash balance of ~$1.8B. Roughly, that means the company had to burn ~$1.8B to get to the size of business they are today.

Granted, Instacart also hit free cash flow positive for the first time in 2022. So I don't even want to make the argument of this business being a cash inferno like others I've written about (like WeWork or Hopin). Instead, the reality is that you can't just "not raise" the capital post-Series B. Instacart, at least in its current state, needed at least ~$1.8B to generate that return for those early investors.

The headlines will talk about investors like Sequoia, who invested in Instacart's $8.5M Series A in 2013 at a $75M valuation. That position at the IPO is worth ~$1B (not accounting for dilution and future purchases.) Exceptional by any and every standard! But that's not the whole story. Sequoia has invested $300M total to generate a total ~$1.4B stake. Still a great 5x return. But for that Series I investment at $39B? Not as great in isolation.

Now, again, I'm not criticizing Sequoia's investment in Instacart. A 5x return on $300M of capital is what dreams are made of. But Sequoia illustrates two things about the value chain of capital that I'll explore more below:

Capital Dependency: A company's "terminal value" can look great for early investors, while being dependent on later investors

What's It Worth: The success of an early investor's return is determined based on what a later stage investor decides the company is worth

Sequoia has the benefit of having invested along the way, though 85% of their $1.4B return came from that initial Series A investment. But what if you're Fidelity or T. Rowe investing for the first time at that $39B Series I? You're completely in the hole.

And that's not just true for one excessive 2021 round. Remember that up to the Series B (the last round to beat the S&P 500), the company only raised $55.7M. But they would go on to burn at least $1.8B to get to where they are today. That means that the return for Sequoia and a16z in the Series A / B is dependent on an additional $1.7B of unprofitable capital.

Capital Dependency

A lot of people like to use language like "passing the bag" and "bag holders" to describe the "capital value chain" that I'm outlining. But that isn't necessarily quite right. In crypto, bag holders are often people who are left with nothing, whose investments are the only driver of enrichment for earlier participants in the chain. But that isn't always the case in venture.

Look back at our Instacart example. The early investors hold a much higher return than later investors, but all of them still own shares in a near-profitable ~$10B business with $1B+ in revenue. That's not just a bag of hot air, it's a real business.

I've written before about a point that Bill Gurley was making back in 2016 about how capital dependency has become a function of capital supply:

“Back in 1999, if a company raised $30mm before an IPO, that was considered a large historic raise. Today, private companies have raised 10x that amount and more. And consequently, the burn rates are 10x larger than they were back then. All of which creates a voraciously hungry Unicorn. One that needs lots and lots of capital (if it is to stay on the current trajectory).”

Some people refer to this as the VC ponzi scheme, or the financial circle-jerk (again, my Mom reads this blog, so I'm not going into that one.) You want to know the deepest irony of both of those examples, though? The first one is Chamath, and the second one is SBF. Some of the greatest examples of financial "he who smelt it, dealt it."

The point that these goobers, and a lot of other less criminal people, have made is that the pursuit of growth has been the thing that expanded company's appetites for more and more capital. Never mind whether the LTVs justified the CACs, it was about growing. Unsustainable business models have created a generation of businesses addicted to more and more capital. That is where capital dependency comes from.

However, as much as companies are so often dependent on future capital, the extent to which that capital is under water isn't a foregone conclusion. It's a function of what people are willing to pay, and in particular what they think the next person will be willing to pay.

"What's It Worth?"

During times of economic plenty, you start to feel free from everything. Public markets, inflation, interest rates, job markets, everything feels decoupled. "Divorced from reality" was probably the phrase that best sums up 2020 to 2021 in particular. On the opposite side of the coin, times of economic distress reinforce just how dramatically everything is interconnected.

Early in 2022, when the markets started to correct, I remember seeing this tweet from Matt Turck and it perfectly summed up a lot of the confusion that persisted in the world of venture funding.

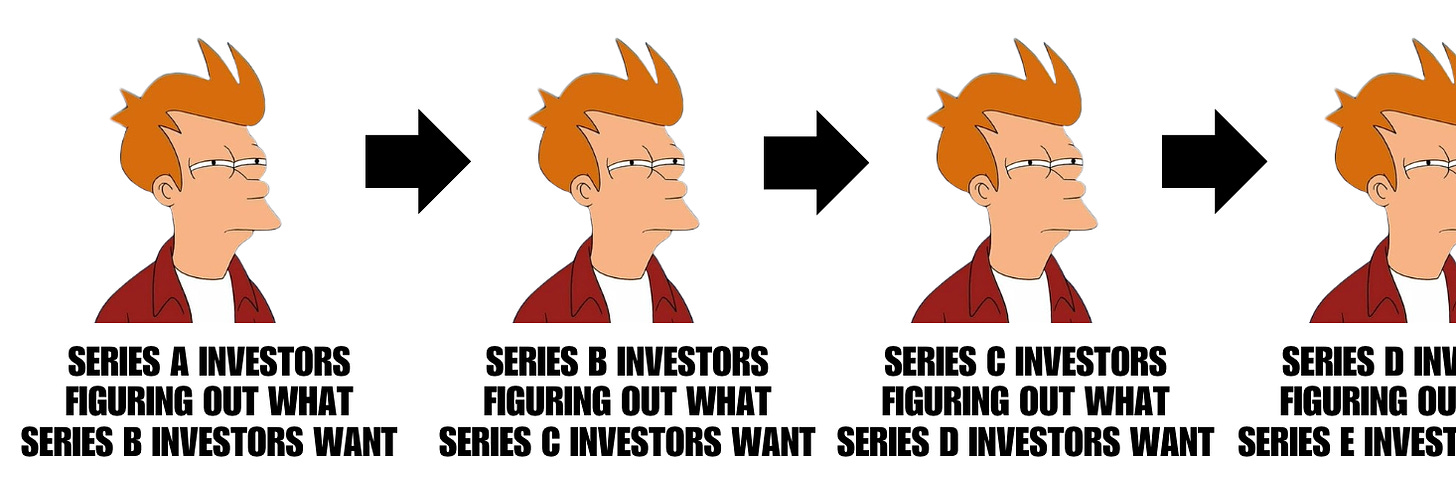

This drives home another point of the capital value chain. In a world of plentiful capital, most VCs weren't as focused on what could raise follow on capital. If a psycho with a commercial real estate business can raise $20B, then anyone can raise anything! But the sudden constraint on capital made VCs realize just how dependent they are on downstream capital.

This dynamic reminded me of a quote that I can't find, but I think is a Charlie Munger-ism. The idea that in public markets, you're not trying to predict what the market will do. You're trying to predict what other people predict the market will do. Howard Marks has written about this idea quite a bit, that every forecast would have to account for the reactions of every participant in a market (which is why he hates forecasts):

"Further, a model will have to predict how each group of participants in the economy will behave in a variety of environments. But the vagaries are manifold. For example, consumers may behave one way at one moment and a different way at another similar moment. Given the large number of variables involved, it seems impossible that two “similar” moments will play out exactly the same way, and thus that we’ll witness the same behavior on the part of participants in the economy. Among other things, participants’ behavior will be influenced by their psychology (or should I say their emotions?), and their psychology can be affected by qualitative, non-economic developments. How can those be modeled?"

In venture, the same dynamic exists. But its much less constrained than the entire public market. In private markets, you're primarily focused on understanding what a VC would be willing to pay. And VCs are sort of lemmings; all using the same decision-making heuristics to determine what something is worth.

The resulting constraint in capital during this market correction has meant that VCs are becoming more and more “bubble-minded,” focusing on what the next stage of capital will want, not necessarily what the best business might be in the long-run.

Worth is a Function of Time

Another element of what something is worth is understanding when you can sell. I've written before about how venture funds are actually not really the most effective long-term investors:

"Venture funds, contrary to the marketing framework they like to reinforce, are not long-term thinkers. They’re a collection of short-term careerists focused on maximizing the amount of success they’re associated with. As an individual investor, your economic interests are not as easily connected to long-term success, but instead short-term performance."

Even when you step back from the individual investor lens, and look at the incentives of the overall fund. Funds have lifecycles in which they're trying to deploy and reclaim capital. Selling is as an unavoidable part of the equation. Compounding in venture is much more limited than, say, a Berkshire Hathaway approach.

In that video by Aswath Damodaran where he unpacks the returns of each round for Instacart, he makes this point about VCs:

"I know over the last few decades, especially the last decade, when VCs were viewed as superstar investors; why? Because we saw stories of incredible success. This is selection bias in what we read. And also, some VCs are relentless self-promoters. They try to promote themselves as people who can judge businesses as amazing guagers of whether a business will pay off. I've never believed this about VCs. I think most successful VCs share more with successful traders than they do successful investors. They play the pricing game. What does that mean? They get judged on timing. When they enter and when they exit."

And when you look at some of the early successes in venture, there really is a significant role that timing played. Take Netscape as an example.

Netscape: Selling At The Right Time

Netscape was a web-browser founded in 1994 when Jim Clark recruited a young Marc Andreessen to be his co-founder. Just four months after being released, it had 75% market share. In August 1995, just 16 months after starting, Netscape went public at a $2.9B valuation with revenue doubling every quarter, before being acquired by AOL for $4.2B in stock in November 1998; ultimately closing at $10B in March 1999.

While Netscape had, at one point, controlled 90% of the browser market in the mid-90s, within a few years after the AOL acquisition Netscape had dropped to less than 1% in 2003 when AOL disbanded the company. The culprit? Microsoft's Internet Explorer. In classic Microsoft fashion, they were able to use their existing distribution to put the IE browser on every computer, regardless of the fact that it wasn't necessarily a better product.

By the time AOL was buying Netscape, the company's market share had already fallen to 41.5%, compared to Internet Explorer's 43.8% share. Netscape is an example of a failed company, and a failed product. Granted, Microsoft was no easy competitor (just ask Slack). But for Kleiner Perkins, who led Netscape's early rounds of funding, or for co-founder Marc Andreessen, the ultimate outcome didn't matter. Their time-boxed outcome was $10B.

That’s one of the obstacles of the value chain of capital. I’ve written before about this isolated scorecard for investors. Investors are not measured by ultimate outcomes (e.g. the company from beginning to end), but rather are measured by intermittent outcomes (e.g. hold periods.) And in many instances, that intermittent outcome is completely divorced from that ultimate outcome.

Therefore, What?

There are a few conclusions we can draw from the capital value chain:

Companies could raise less money: I've written before about the dangers of excess capital. I've also written frequently about how raising venture capital is picking up one end of a stick, but it forces you to pick up the other end of the stick (outcome expectations). Business models are the same (which I wrote about here). The model you pick dictates the amount of capital you need. And that dependence on capital determines how much control you have over your own destiny.

LPs can accept crappier returns: This is another aspect I've written about frequently. The business model of venture capital has invited a plethora of capital agglomerators whose primary business is asset aggregation, rather than generating outsized returns. Firms with $10B+ of active AUM typically have LPs that are fine with 2-2.5x returns, which can justify more capital, and worse outcomes. Smaller funds may think they’re immune, but they have to compete with the prices those capital agglomerators are willing to pay.

Investors and founders alike can acknowledge the zero-sum game: I wrote just recently about the different games people are playing. The environment we've created within which we can build companies is increasingly zero-sum. Outcomes have to be bigger, and more and more companies will get left in the dust of run away expectations. You can just accept that, and only build / fund companies that have the potential to be $5B+ companies.

I could leave it at that. Being aware of the capital value chain has all sorts of ramifications for how you might go about building a business, or how venture funds might determine their strategies. But I'm left with one remaining question: what is the virtue of the capital value chain?

The Warmth of a Capital Bonfire

Some people look at hype cycles with massive amounts of excitement, and capital, and see it through a very 'glass-half-full' lens. While a lot of individual investors may not make money from a hype cycle, there is a valuable social good that comes from increased capital deployment, so the net benefit to society is positive.

Take, for example, the ride share wars. I've written before about the Uber vs. Lyft cash inferno. Some would argue that the billions of dollars that went into that space may not have generated positive investment outcomes for everyone, but it created a good product for people, so there was still that net positive.

My own recent experience would indicate the breaking points behind what has been an actually fairly unsustainable business model. As the massive VC-enabled incentives for drivers go away the quality of the service goes down significantly. In some instances, that leaves a hollowed out industry (like taxi cabs) that may end up worse than it was before. Time will tell.

But it raises an interesting question; in areas where progress is actually socially advantageous, what is the virtue of significant capital destruction? Take AI, for example. If AI becomes what many of us hope it will one day be capable of, there are massive positive implications for society as a whole. So when a lot of us look around at the billions being deployed into what feel like unsustainable AI companies... isn't that still net positive if it leads to AI breakthroughs?

Here's another way to frame the question.

Is Technological Progress Inevitable?

If we didn't pour billions into AI... would we still get the same progress? If we hadn't had the dotcom bubble, would we still have Amazon? Or Google? I'm inclined to believe that progress is not inevitable, and needs to be coaxed with the right environment. But I'm also inclined to believe that it isn't just a function of capital.

First, the inevitability of technological progress.

I'm reminded of a video of Neil deGrasse Tyson where he talks about the Islamic Golden Age. He talks about how 2/3 of the stars with names have Arabic names. How algebra is an Arabic invention. From AD 800 to AD 1100, Baghdad was the center of the Islamic Golden Age, that led to a lot of these types of discoveries. Tyson argues that a particular character, al-Ghazali, led to the decline of science in the Islamic nation. His codified principles of "what it means to be a good Muslim," included assertions like "the manipulation of numbers is the work of the devil," or that "actions that you see in nature are the will of Allah."

He makes the point that the removal of science and math from the center of Islamic culture unwound the whole enterprise of that golden age. He also makes the argument that, while Islam has risen to become the second largest religion in the world, with 1.9B adherents, it contributes a small portion of technological advancements in the world. One anecdote is the fact that while Muslims made up "23 percent of the world’s population, as of 2015, only 12 Nobel laureates have been Muslims, whereas 193 (22 percent) of the total 855 laureates have been Jewish, although Jews comprise less than 0.2 percent of the world’s population."

In a great piece by L.M. Sacasas entitled "Resistance Is Futile: The Myth of Tech Inevitability", there is a quote from historian Thomas Misa that really stuck out to me:

“We lack a full picture of the technological alternatives that once existed as well as knowledge and understanding of the decision-making processes that winnowed them down. We see only the results and assume, understandably but in error, that there was no other path to the present. Yet it is a truism that the victors write the history, in technology as in war, and the technological ‘paths not taken’ are often suppressed or ignored.”

Looking at the curve of history, I think it is fair to say that technological progress is not inevitable. The pursuit of progress is critical to manifesting it. But that doesn't mean that capital destruction is a necessary ingredient.

Take, for example, the amount of capital that other cities or countries have spent trying to replicate the environment in Silicon Valley. Despite the billions these other locations have invested attempting to attract the kind of technological revolution that we've seen in the Bay Area over the last 50 years, no one has succeeded.

So it isn't just capital. Instead, I think we should focus less on the capital value chain, and more on the innovation value chain.

The Innovation Value Chain

We should, instead, be focused on all the drivers of innovation and progress that make the world a better place. People have skewered the ESG-flavor of corporate social responsibility, and rightfully so in many cases. There are plenty of examples of corporate green-washing that have nothing to do with "innovation" in the broadest sense (other than innovative marketing and financial massaging).

I think purely focusing on things through a capital lens and what the next person will be willing to pay leads to a lot of conformist views. This deprioritizes things that take a very long time but have outsized impact, in favor of things that can have short-term pay off, regardless of the actual impact. "What you measure is what you get." So we could start quantifying better the elements of creation beyond just the capital inputs and outputs.

*Thanks to Alexa Kayman, Andrew Michelson, Sachin Maini, Cory Anderson, Spencer Stewart, Tyler Lasicki, Sachit Bhat, Catherine Zhao, Jason Wong, and Anna Bulajic for jamming with me on this topic.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

This one is really insightful.

• Capital Dependency: A company's "terminal value" can look great for early investors, while being dependent on later investors

• What's It Worth: The success of an early investor's return is determined based on what a later stage investor decides the company is worth

Memo to myself: https://share.glasp.co/kei/?p=9YyA01aTNBxJudjNObtc

Great reminder that all the 'smart money' in the world is just driven by individuals hiding behind big institutions, and these individuals are still human - hence the Keynesian beauty contest.